A history of state repression in Guerrero, Mexico

- December 12, 2014

Authority & Abolition

The recent massacre of 43 students shocked the world, but was only the latest act in a long history of state repression in Mexico’s Guerrero region.

- Author

The Iguala massacre woke up a society that seems inured to widespread corruption, impunity and brutal violence. Recently, Mexican society did show a reaction to other massacres, like the one that occurred in Monterrey where 52 people died locked up in a casino building after it had been deliberately set on fire. Or in Tamaulipas where 72 Central American migrants heading to the U.S. were kidnapped and murdered after they refused to become hit men or pay ransom for their release. However, what happened in Iguala was different. It was a clear act of political repression and this time the participation of state agents as perpetrators was impossible to hide.

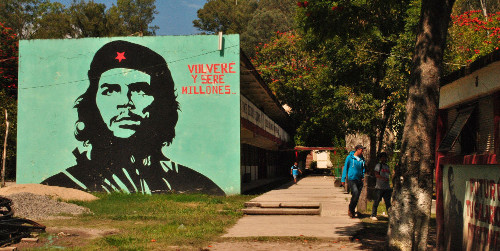

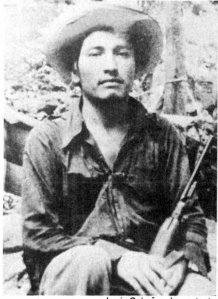

Moreover, the massacre targeted a focal point of political activism in Mexico; a school of teachers, a ‘school of democracy’. For more than half a century, teachers from Ayotzinapa have been fighting against corrupt policemen, homicidal soldiers, paramilitary forces, caciques (local strong men) and now the narco state. Ayotzinapa has provided a disproportionate amount of leaders to Guerrero’s social movements, including Lucio Cabañas, founder of the Partido de los Pobres (PDLP), the most important rural guerrilla organization during the 1970’s.

On one side the Iguala massacre is an archetypical case — so recurrent in Mexican history — in which a peaceful protest turns into a rebellion because of state repression. On the other hand, although it is by no means new, the fact that repression was carried out by public officers and policemen who were collaborating with hit men from a criminal organization is a present-day distinctive. In such a case a major social outburst is hard to avoid. In this moment, actions taken by the government and civil society will determine if a system collapse will be avoided. As Trejo states, “in Iguala past, present and future converge.” This convergence may be shown by tracing a long cycle of mobilization and repression in Guerrero where impunity has always prevailed, from la guerra en el paraíso to Iguala’s inferno.

Not a Revolution, but a ranchero revolt

According to Ian Jacobs, author of The Ranchero Revolt, Guerrero’s history was shaped by its physical geography. In the early twentieth century there were very few roads in a region with very rough terrain. The lack of roads made land unattractive to elites during the Porfiriato. Hence, the problem of stolen lands did not acquire the dimensions it took in the neighbouring region of Morelos, where sugar cane haciendas dispossessed peasants and generated a fertile ground for the Zapatista rebellion of 1911.

In contrast, Guerrero did not experience widespread usurpation of communal lands in the early twentieth century. Hence, the political evolution of the region was different; without a rebellion such as the one led by Zapata, the Porfirian structure of caciques remained intact during the Mexican Revolution and was even reinforced when caciques disguised themselves as ‘revolutionaries’ and were accepted by the regime during the post-revolutionary decades.

In Guerrero, the Figueroa brothers (Ambrosio and Francisco), who betrayed Zapata on many occasions, imposed themselves as the main overlords. They became the quintessential caciques in the region and founders of the everlasting Figueroa dynasty, a sort of ‘Somosa family’ in Guerrero.

December 30, 1960, Chilpancingo, Guerrero

A student demonstration claiming university autonomy was repressed at Chilpancingo, Guerrero’s capital. Seventeen protesters were killed. The massacre forced the governor, general Raúl Caballero Aburto, to resign (Cervantes, 2007). The student uprising evolved into an urban popular movement with presence in many state regions spearheaded by the Asociación Cívica Guerrerense (ACG), a political organization created in 1959 by regime opponents. There were many teachers among them.

December 30, 1962, Iguala, Guerrero

During 1961 the popular movement grew in strength. The provisional local government called for elections to be held in December 1962 in order to renew state and local authorities. The ACG presented José María Téllez as their candidate for Guerrero’s governorship. After losing the elections, they protested against what they considered to be a fraudulent result. Again, demonstrators were confronted by the police and the military.That time the toll of the repression was 8 deaths and 156 arrests.

The ACG leader Genaro Vázquez fled the state but was captured in 1966. ACG members rescued him in 1968 from the Iguala prison and fled to the Sierra (Guerrero’s western highlands), where Vazquez renamed the ACG as Asociación Cívica Nacional Revolucionaria (ACNR) and stated that members of his organization were convinced that the armed struggle was the only means to transform the situation (Salgado, 1971).

May 18, 1967, Atoyac, Guerrero

A protest rally took place to demand the destitution of the primary school director and the school committee. The rally was led by Lucio Cabañas. The police had warned Cabañas that they would not tolerate any demonstration, so they opened fire when Cabañas started to speak, killing five people, including a pregnant woman. Like Vazquez, Cabañas also fled to the Sierra and formed the Partido de los Pobres and its armed branch; the Brigada campesina de ajusticiamiento (Peasant execution brigade).

1960s – 1970s, Guerrero, La guerra en el paraíso

In the Sierra, the rebels found the fertile ground for rebellion that was absent at the beginning of the twentieth century. The federal and state governments were carrying out two large-scale modernization projects in Guerrero, both taking place either in the Sierra or in localities close to it. Partly financed by the World Bank, the first project consisted of the construction of a series of dams and civil engineering enterprises through the Balsas River, mainly for energy production.

The goal of the second project was to develop the port of Acapulco and its surroundings as a mayor international tourist destination. This state-sponsored modernization was planned by a central bureaucracy interested in economic progress at the national level but caring little about concerns of the local population. Hence, it became a process of authoritarian economic exploitation.

During the 1960’s and the 1970’s labour conflicts erupted in the Sierra; land was taken away from peasants and forests were cut down by foreign timber companies. Popular protest emerged with a broad set of demands ranging from land redistribution, an end to forest exploitation, attendance of educational, health and socioeconomic needs of the popular classes, rights to unionize, democratic transparency, and community decision making.

The wave of mobilization was severely repressed and guerrilla organizations nurtured the grievances. According to Trejo, repression in Guerrero in the 1960’s and 1970’s reached levels of the guerras sucias in Chile and Argentina. According to the special prosecutor’s office, the Fiscalía Especial para Movimientos Sociales y Políticos del Pasado (FEMOSPP), that was investigating the guerra sucia, at least 482 forced disappearances took place during that period.

May 30, 1974

PRI senator Ruben Figueroa Figueroa (Francisco’s nephew) was kidnapped by the PDLP. As asked by the rebels, the Mexican government announced the retrenchment of the army from Guerrero rural areas to the headquarters, but Guerrero’s countryside was heavily militarized in secret. Soldiers were looking for Figueroa and hunted down the PDLP. Cabañas died in combat, and Figueroa was rescued. In 1975 he became the governor of Guerrero.

The FEMOSPP, with more than 500 oral testimonies and documents from the Mexican national archive (Archivo General de la Nación), asserted that, once Figueroa became governor of Guerrero, he perpetrated hundreds of crimes. Figueroa then ordered arbitrary detentions. The state’s chief of security Mario Acosta Chaparro, together with Alfredo Mendiola, Alberto Aguirre and Humberto Rodríguez, was in charge of executing the victims and throwing their bodies from airplanes in the ocean.

Army and police forces managed to suppress the rebellion in the highlands by killing or imprisoning most of the rebels. By the 1980’s neither the ANCR, nor the PDLP, nor the other dozens of guerrilla organizations formed in the 1970’s, were a threat to the Mexican state.

Carrots and sticks

The ‘stick’ came together with some ‘carrots’. Two of those carrots were particularly important. After wars, reconstruction processes follow. Something similar happened after Guerrero’s guerra sucia. The first carrot meant significant state resources and a new program for land redistribution aimed at winning the ‘hearts and minds’ and avoiding a subsequent rebellion in rural areas. This process can be seen as the state’s “massive incursion” in Guerrero’s eastern highlands, ‘la Montaña’ region. The second carrot was a democratic opening in which former guerrilleros were exonerated and the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) legalized and allowed to compete in the elections.

Nevertheless, no one was held responsible for the crimes against humanity perpetrated during the guerra sucia. Furthermore, the forced disappearances of radical opposition leaders continued despite the process of democratization and government alternation at the federal and state levels. Impunity prevailed. The tension of this historic moment was captured in the closing lines of Carlos Montemayor’s novel Guerra en el paraíso. In the novel, when Lucio Cabañas is shot, a thought resonates while he is falling to the ground: “there is still a lot to be done, to be done, to be done…”

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/iguala-ayotzinapa-guerrero-repression/