Photo: Eleanor Goldfield

Hope of a sustainable future in West Virginia’s coal country

- January 22, 2020

Climate & Catastrophe

An intimate portrait of West Virginia’s “coal country,” where locals plan for a sustainable future amid the devastation wreaked by the fossil fuel industry.

- Author

On the national stage, there is not a lot of chatter about coal anymore. Once the fuel that drove the engine of US “progress,” coal use has plummeted primarily due to market forces and the difficulty in extracting the coal that is left.

Despite the propaganda line, the one thing that has not killed King Coal is regulation — the little that ever existed. For instance, the Obama-era regulations on coal ash ponds that Trump recently proposed scrapping merely put a deadline on dumping toxic coal ash in unlined ponds. In other words, rather than outlawing toxic dumping straight into earthen holes, Obama let it continue under the guise of environmentally conscious oversight. With regulations like these, there are not any industry constraints that deregulation can loosen. Put simply, the King is dying. The lustful spark between capitalism and coal is fading.

Wilma Steele, co-founder and board member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum has watched the downfall of coal from the front lines. Married to a former coal miner, and born and raised in the heart of coal country, she is clear about what is killing coal. “It’s the market. That’s all it is,” she says. “If the money’s there, they’re gonna go after it. And the Presidents will follow along.”

When the money was good, coal was protected. On November 7, 1973 for instance, in the throes of the oil crisis, President Nixon addressed the nation, appealing to industries and utilities to stick with coal rather than converting to oil in the interest of energy independence. Sound familiar? A report released by Huff Post in late November 2019 unearthed a coal industry publication from 1966 that proves big coal knew about the science behind climate change.

As with Exxon, however, the profit far outweighed the realities of impending climate chaos. The coal industry poured millions into propaganda that uplifted coal as a necessary job and energy creator.

“Mine slower, plan faster”

“Prove You’re Against Coal Mining — Turn Off Your Electricity” reads one bumper sticker I pass on the Highway 64 outside of Charleston, West Virginia. At a state visitor center, you can buy miniature bibles and angels sculpted from coal. To put it mildly, this coal culture runs deep. And today, despite backburner status, coal company bankruptcies and market downturn, big coal is trying to float on entrenched loyalty from both people and politicians in order to go after what is left in a hurry.

“We’ve been saying for years: mine slower, plan faster.” Wilma folds a red bandana in her hands and smiles a deeply kind yet resolute smile. Her husband Terry nods in agreement. A former mine worker and member of the United Mine Workers of America, Terry Steele proudly says that being part of a union is the most important thing he has ever done. The UMWA were not only a big part of Terry’s career, they are a big part of the Mine Wars Museum, a collection of exhibits that highlight the largely erased history of radical solidarity and labor organizing in West Virginia coal country. The museum is on the same block where the Matewan Massacre took place, a climax event for workers’ rights that propelled miners to take up arms in the Battle of Blair Mountain a year later.

Terry Steele, co-founder of the Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, West Virginia. UMWA member and former coal miner.

Terry is still active in UMWA, and is again proud to announce that it has branched out to work outside of mining, for instance in nursing homes. His hope is that they can branch out to renewables as well, giving folks in the area good-paying jobs in green energy. “That’s how you make an environmentalist,” Terry says leaning back. “You gotta give somebody something to work at. You can’t just put ’em out on the street with nothing.”

This is where the call to “mine slower, plan faster” comes in. West Virginia’s rolling hills are ideal for both wind and solar. And the flattened planes of former mountain top removal sites could easily become hilltop beacons of renewable energy, without needing to destroy any of the remaining hills or hollers. Indeed, many of the locals have already been planning and doing for quite some time.

Paul Corbit Brown, president and chair of the Keepers of the Mountain organization lives off the grid in a solar powered home accessed via quaintly southern directions: past the gas station and local store, past the church and a right after the train tracks. There is no address and no cell service. But there is plenty of water, heat and electricity. Paul’s home is an example of what could be, and his work includes not only hosting a Solar Music Festival every year but also reaching out to local folks who could make the switch to renewables and thereby become other active examples of what a just transition might look like here.

The problem, as Paul says, is how to keep up with the destruction. Rather than mining slower, the industry literally blew the top off of traditional mining, opting to decapitate entire mountain ranges in order to access the harder-to-reach coal, much like fracking gets at difficult to reach oil and gas deposits. As Terry says, “It’s only the scraping of the peanut butter jar, trying to get the last of that peanut butter.”

And while folks on the ground plan and work for sustainable futures, government and industry are not only mining faster, they are building fracking infrastructure that will replace coal with gas. The transition is an easy one for industry — fracking can use the same tricks and tools that the coal industry did, like the separation of surface and mineral rights. Surface rights are just that — ownership of the surface of a specific property. Mineral rights, however, dictate that you own and have access to minerals beneath the surface of a property. The fracking industry has used this cornerstone of resource extraction to access gas beneath surface properties they do not own or have permission to be on.

“Don’t expect protection”

Fracking companies have tried to smooth over their insidious work by pouring money into specific areas of the community. In the heart of fracking country, Doddridge County High School got a brand new $12.8 million athletic facility this year, complete with batting cages, an Olympic-style gym, a new football field and an eight-lane track. At the same time and not far away from the glistening new facility, a plan to rebuild the local playground put forward by several companies has yet to materialize after more than a year.

Linda Ireland, a former school teacher in Doddridge County explains that kids in high school are targeted by the fracking industry for the meager number of jobs that exist, and both administrators and educators at the school avoid criticizing fracking, even in classes that focus on farming and agriculture.

Still, not everyone is on board the fracking train. Lynn and James Beatty retired to West Virginia from the DC area, seeking rural calm. Soon after they moved in, however, a compressor station moved in too. “It’s like trying to live in the middle of a truck stop with all the 18-wheelers running,” Lynn says. “No more peace and quiet. We didn’t wake up to bird song in the morning, like we had planned. We didn’t see the deer. We had chickens – they stopped laying.”

James explains his frustration further, pointing out that they have never seen an EPA representative “do any kind of study, a walk through, nothing. The county and state gave the oil and gas company a carte blanche.” Complaints to the company were either ignored or dealt with in an almost comically absurd way. For instance, when the Beattys and their neighbors protested about the noise, a worker was sent to the property with a noise level sensor. “They set up the [sound sensor] equipment, shut down operations for two days and then they started the noise and took their equipment away again,” James explains.

When it came to chemical pollution, the tragic comedy continued. “They sent us a packet of information with at least two pages of toxic chemicals that they put into the ground and then they wanna test the water. So, what did they test for? Not one of those chemicals on those two pages.” Lynn laughs, shaking her head. “It’s hard to win around here, it really is.”

Compressor station with a pipeline at the top right. Compressor stations compress gas to push it down the pipeline.

Complainants to government do not have much luck either. Linda told me that when folks did voice their complaints of fracking with the County Commission, they were met with indifference bolstered by the age-old argument that these companies are not breaking any laws. “Almost everything that goes on is legal. They’re coming in with a permit,” Linda says, shaking her head. “You feel like there’s nothing you can do because you have these companies with all their resources and the state seems to be on their side as well.” Mirijana Beram, another resident of Doddridge County, told me that the West Virginia DEP (Department of Environmental Protection) is often referred to as “Don’t Expect Protection.”

Reports of explosions, strange smells, polluted water and property destruction have been largely ignored by the DEP. The largest processing facility in the nation is in Doddridge County, WV, and it is expanding. At the same time, construction of more processing plants, compressor stations and drill pads rolls on unabated.

hope of a sustainable future

“It’s a hard road of hope,” Paul says. He points out that as West Virginia has been a resource colony since its founding, it is damn difficult to combat years of industry brainwashing. “At least I have a job” is always the final resignation. When a coal giant steals pensions, when fracking poisons water and air, the attention is on the single bad company, not the industry as a whole. Furthermore, much of the devastation is hidden. Strip-mined mountains are shaded from highways by rows of trees. Frack pads hold a low profile and turfed-over pipelines cover the fact that for every acre of frack pad, there are 15 acres of pipeline for transportation.

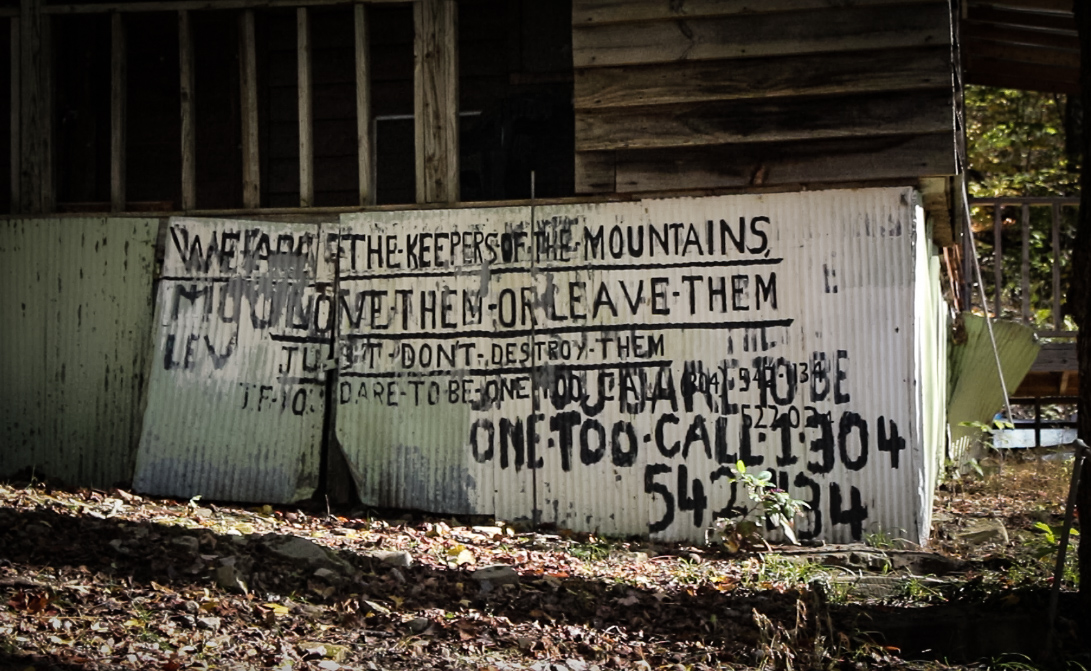

Sign at Kayford Mountain, home of the Keepers of the Mountain. Sign reads: “We are the Keepers of the Mountain. Love them or leave them, just don’t destroy them.”

In spite of these industry tricks and tactics, in the hills and hollers, people are fighting and building. In a variety of ways across the state, people are spreading the word to locals and visitors and organizing in their communities to build a better future. I tagged along with Paul on a tour of Kayford Mountain, the site of a powerful battle against big coal that saved a gorgeous mountaintop from destruction. Paul gives tours mostly to college students here, explaining the realities of mountaintop removal, the history of coal mining and a potential future that kids their age can construct.

Terry and Wilma are part of the Mine Wars Museum. “It’s grassroots organizing when you tell your history and tell where you came from,” Terry says. “Our history is showing other people in the country what solidarity means, what you can do when you organize,” Wilma says. Mirijana and Linda give in-depth fracking tours all along Highway 50, the fracking corridor of West Virginia. South Wings offers flyover tours to journalists and environmentalists because so much of this devastation can only be understood from above. And at the same time, so much of what is beautiful can also be understood — from above and from the ground.

It is not just the nature: it is the people. If there is one terrible lie the industry has managed to promote most effectively, it is the idea that West Virginia is beyond hope — that the nature is too damaged to bother protecting anymore, and that the people are disposable, easy to cast aside with opioids, coal and fracking. This lie has festered in the minds of people outside and inside the state. It is a lie that keeps people down and disengaged, but that can be knocked out by connecting people with that radical past and the hope of a sustainable future.

“Like this red bandana,” Wilma says, smiling again. “The term redneck originated right here.” It comes from the Mine Wars in southern West Virginia when immigrant miners marched alongside Black miners, tied red bandanas around their necks and demanded basic human rights from the coal barons.

This past glimmers in the present. And folks all over the world can learn a lot from this cast-away state. We would all do well to be proud rednecks.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/hope-of-a-sustainable-future-in-west-virginias-coal-country/