Photo: Lorie Shaull

Of love, hate, hope and despair: ten theses on Trumpland vocabulary

- January 18, 2017

People & Protest

How are we to navigate the ideological struggle over politically charged concepts that can either rally people to the streets, or make them stay at home?

- Author

“Our word is our weapon,” declared Subcomandante Marcos once upon a time. What he could have added was that words are sites of struggle in their own right too.

As we prepare for Trump’s inauguration on Friday and make plans for the four long years of fighting that will follow, it’s useful to recall the fights that have recently erupted around loaded concepts like “love,” “hate,” “hope” and “despair.” When properly understood, these skirmishes help to bring the tensions that shape our reality more clearly into view. For this reason, they are indispensable guides as we struggle to analyze our situation and determine the course of action we shall follow.

For Raymond Williams, words become “brittle” in “periods of change,” when the taken-for-granted associations between concepts and things begin to break down. Indeed, the variations in meaning that arise within a word signal “actual alternatives” through which “problems of … belief and affiliation are contested.” Trump’s election has initiated such a contest, and the meaning of “love,” “hate,” hope,” and “despair” hangs in the balance. So too does the reality to which these concepts refer.

I

Even before the election results were confirmed in November, premonitions of the war of words we would be waging could be detected in Hillary Clinton’s insistence that “love” would trump “hate.” As far as slogans go, it wasn’t bad, and — since her defeat at the polls — the defiant proclamation has migrated to thousands of demonstration placards.

Despite being a weird inversion of the normal trajectory plotted by political slogans, where inscrutable grassroots assertions go on to become shiny branded sound bites, I’ll confess that (on some level) this development makes me smile. At very least, it allows us to imagine that the new tyrant king will be brought down, not by some Democrat hack, but by the people themselves.

Still, both the slogan and its newfound resonance make me worry. Partly, this is because slogans (good though they may be) can’t be lifted from the playbooks of the rich without making us beholden to them in some way. Mostly, though, I worry that our collective insistence that “love trumps hate” signals an allegiance to a more general — but also more dangerous — habit of political thinking that must be opposed at all costs.

II

Normally, I’m wary of arguments that collapse the distinction between politics and semiotics. Nevertheless, the genius of Clinton’s campaign slogan can only be understood by considering how it effectively turned “love” and “hate” into mutually exclusive, antithetical propositions. Within the confines of this new and widely adopted rhetorical universe, siding with love means fighting against hate. At its logical conclusion, the slogan even suggests that those who side with love are in fact love itself since, as its most immediate referent, “hate” can only mean hate incarnate, Donald Trump.

What’s more, the very fact that activists across the country have chosen to side with (and thus in some sense to believe that they are) “love” guarantees that they will be victorious. After all, the slogan is declarative, irrefutable: “love trumps hate.”

Reasoning of this kind can be contested in a variety of ways. What remains most objectionable about it, however, is that it reduces politics to a process of logical representational negation. According to the implicit rules of this game, which also find expression in the unending movement debate about violence, it is presumed that, by adopting the position we perceive to be most favorable within an established and zero-sum binary, we will somehow end by negating (canceling) our enemy.

In fact, the main thing such an arrangement negates is the possibility that anti-Trump forces might recognize “hate” as a legitimate and animating power.

III

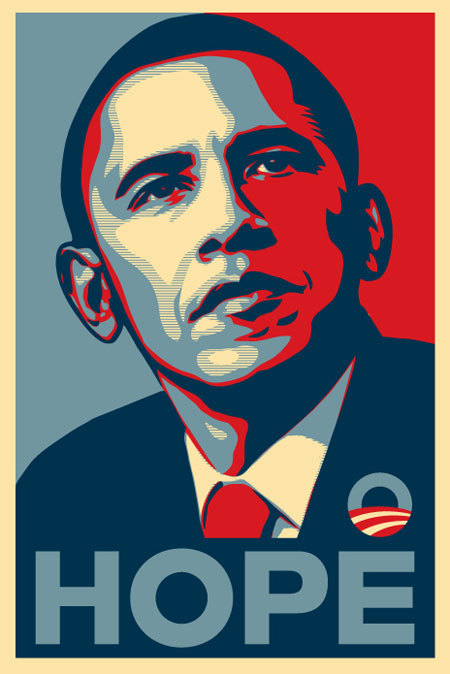

When Obama won the White House in 2008, the official watchword was “hope.” As inspiring as this single-syllable slogan may have been to Democratic Party supporters, however, it’s important to acknowledge that the concept remains marked by a deep ambivalence.

When Obama won the White House in 2008, the official watchword was “hope.” As inspiring as this single-syllable slogan may have been to Democratic Party supporters, however, it’s important to acknowledge that the concept remains marked by a deep ambivalence.

At face value, “hope” registers as a noun; it is the signifier assigned to Obama, who in turn becomes the literal expression of “hope” in the world. From this standpoint, to believe in “hope” meant believing in Obama. It was a love affair that could not last. Just beneath the glossy surface, “Hope” began revealing its more brazen, sinister side. At its threshold, it even expressed itself as a verb.

Cast in this new register, “hope” became the sadistic imperative that Obama would issue to those he ruled. Of a piece with neoliberalism’s injunction to happiness, it was an order barked at those toiling uncertainly in the shadows. How could it be otherwise? After all, the inspirational poster that Shepard Fairey designed for the Obama campaign was nothing more than a sanitized simulacral iteration of the more ubiquitous source material from which it derived.

IV

Attentive to its political ambivalence, people have regularly worked to stabilize the meaning assigned to “hope” by conjoining it to “despair,” its putative antonym. In the wake of Trump’s oligarchic ascent, “despair” has even encroached on the cognitive space once reserved for “hope” when trying to explain people’s motivation to act.

Though it remains difficult to imagine as a slogan (and though it continues to find expression primarily as a noun), media commentary has instinctively invoked “despair” to explain everything from the desire to “Make America Great Again” to that wretched feeling that overwhelmed New Yorkers as we made our collective walk of shame to some latté-swilling corner spot the morning after November 8.

According to the New York Times, “despair” was what motivated Trump supporters in desolate steel towns like Ambridge, PA. Huddled around flickering TV screens like campfires in the wreckage of a once imagined community, these voters rallied to dodge the “desperate vision of America” they associated with a Clinton coup.” In the end, they weren’t alone, and those casting ballots across America’s sacrifice zones — whether suburban stuffed or rustbelt starved — lined up to ensure that this particular vision of hell was vanquished in the night.

V

As bad as this future might have been, however, Democratic coronation nightmares did not exhaust despair’s profound range. According to journalist Sarah Sloat, Trump’s charismatic appeal correlated directly to the massive rise in opioid-fuelled “despair deaths” under Obama’s reign.

Succumbing to addiction while America slouched toward some new Camelot for “hope” to be born, “the social and spiritual condition of rural whites” became indistinguishable from their “growing sense of hopelessness.” In our current rhetorical universe, such hopelessness can only mean despair and, for journalist Howard Rhodes, “to describe this condition as despair is apt.”

Despite its role in tearing down Obama’s “hope,” however, “despair” has not been the currency of Trumpland alone. According to the Chicago Tribune, a national texting service providing “help to people in emotional turmoil” witnessed a doubling of assistance requests on election night.

For their part, some Chicago-area colleges chose to alert their students to available “mental health services” to help “process their emotions” in the wake of Trump’s victory. Following suit, left-wing news website Alternet even posted a helpful guide detailing “5 Ways to Prevent Yourself from Despairing Over Donald Trump’s rise.”

VI

In an effort to ward off despair, movement radicals exhumed Joe Hill. A folk hero in the truest sense, even a looming death by firing squad could not prevent him from insisting (might even have compelled him to insist): “don’t mourn, organize!”

On November 9, 2016, radicals unfurled Hill’s banner above dozens of articles, statements and declarations of war. Hill was not our only source of solace, however. Attentive to the collective shock and sensing the danger of letting despair set in, movement author Rebecca Solnit briefly made her Hope In the Dark available as a free download. By the end of our first day in Trumpland, the lesson was clear: cultivating hope in the face of despair was a necessary precondition to winning.

Because radicals identify with a world that does not yet exist (or that exists, as Durutti put it, “in our hearts”), we know that this world must be created, drawn out of the existing one. Premonitions of this kind are the revolutionary bedrock upon which hope is built. They connect hope to “imagination,” a concept that, for Marx, was foundational to the human labor process — and ultimately to politics itself.

Even a Romantic like Samuel Taylor Coleridge could intuit that “Work without Hope draws nectar in a sieve, / And Hope without an object cannot live.” Indeed, hope becomes hopeful through practical human activity. But alongside the bonds he sensed between hope and the human labor process, Coleridge’s sketch can’t help but alert us to some of the concept’s dangers.

VII

As eight years of Obama have made clear, “hope without an object” is a deadly strategy of rule. For critical theorist Ernst Bloch, it amounted to little more than “booty for swindlers.” Far from inaugurating the transformative human labor process, “hope without an object” marks the outer limit of what we imagine to be in our control. We buy the lottery ticket and then hope to win. When we start hoping in this way, we concede that the outcome is no longer up to us. The result is anticipation, the characteristic posture of those who wait for God.

Although he directed his greatest hostility toward Christians, Nietzsche’s famous attack on “a hope so high that no conflict with actuality can dash it” needs to be heeded by all. Following the Ancient Greeks in denouncing hope’s ability to keep unhappy people passive, his insights echo throughout the contemporary radical rediscovery of Antigone, our patron saint of sovereign contestation. Recounting the planned treason to her sister Ismene, the latter balks. “Without hope,” she implores, “even to start is wrong.”

Unmoved, Antigone responds: “Talk like that, and you’ll make me hate you; and he, dead, will hate you, and rightly, as an enemy.” For Ismene, hope pertained to the world as she found it. For Antigone, it was precisely this premise that could not be endured.

VIII

Despite the apparent stability it gains by being enlisted as hope’s antithesis, “despair” is marked by a similar conceptual ambivalence. Hardly surprising, then, that both terms should so easily be associated with contamination. For Auschwitz survivor and literary giant Primo Levi, “despair is worse than a disease.” This did little, however, to change the fact that — in his view — hope too was as “contagious as cholera.”

Recounting the trials endured by a romantic band of partisans struggling to destabilize the Nazi regime, Levi acknowledged “two defenses against despair.” These were “working and fighting.” However, since recommitting to the human labor process and reconnecting with politics (not as representation but as violence) is sometimes hard, he also acknowledged a third defense. This involved “telling one another lies: we all fall into that.”

In such moments, false hope becomes a false resolution to true despair. In contrast, the true confrontation with despair brings with it true work — and true fighting too.

IX

Evaluating the political trajectory of the Weather Underground, Tikkun editor Michael Lerner found that despair had led the group to grossly miscalculate. Indeed, their posture amounted to nothing less than “the final admission of despair” since, from their perspective, “those whom one was traditionally supposed to organize become one’s enemies.” Consequently, “‘fight the people’ must replace ‘power to the people’ as the summary of the Weatherman program.” As far as Lerner was concerned, such a program could only end in defeat, since “fighting the people does not cause radical breakthroughs in their consciousness; it makes them want to institute repression instead.”

It’s a sobering assessment. But while Lerner’s tale has much to teach as we struggle to gain our bearings in Trumpland, the idea that despair inevitably signals a political program’s inadequacy must be reconsidered. Indeed, even Lerner advocated breaking people from their allegiance to the hopes that kept them ensnared. “Part of the white revolutionary’s job is to show white workers how phony their privileges are,” he said. Such phony privileges include those of:

selling one’s labor so one can buy poisoned foods, shoddy goods and cardboard houses in an environment being completely destroyed by capitalist avarice; of producing goods for someone else’s personal profit; of raising children who will die in foreign wars to protect the investments of the bosses; of relating to other human beings as objects who will screw you if you do not screw them first; and finally the privilege of losing the love and respect of your children since they are beginning to see the price you paid for the TV set and second car under capitalism was the exploitation of blacks and Third Worlders — an exploitation they cannot accept.

Despite condemning the despair that had animated the Weatherman program, Lerner’s analysis ultimately yields a demand to intensify awareness of the intolerable so that we might break white workers from false hopes. At this point, despair discloses its positive, generative function. For Bataille, despair of this kind “results in neither weakness nor dreams, but in violence.” The trick, however, is in “knowing how to give vent to one’s rage.” Will we “wander like madmen around prisons,” or will we “overturn them?”

X

Given despair’s potentially generative character, it’s not surprising that our rulers insist on hope. For Machiavelli, cunning rulers were notable for taking “great care … not to reduce an enemy to total despair.” Indeed, “Julius Caesar … used to open a way for [his enemies] to escape after he began to perceive that, when they were hard pressed and could not run away, they would fight most desperately; he thought it better to pursue them when they fled, than to run the risk of not beating them while they defended themselves with such obstinacy.”

Applying this insight to a thought experiment involving a defensive scenario, Machiavelli concluded that, if he were to build a fortress, he “would make its walls very strong” but he would include no “retreating places.” In this way, “the garrison might be convinced that when the walls … were lost, they had no other refuge left.” Under such conditions, they would be certain to give their all.

Since both hope and despair are practically ambivalent, it makes little sense to insist upon either posture. Both are potentially revolutionary, and both run the risk of demobilizing people by making it seem as though matters are beyond their control. In the face of this ambivalence, both hope and despair must be pushed to the point where the burden of responsibility they entail can be acknowledged and cultivated. When disconnected from the active human labor process, hope is booty for swindlers. When brought to its logical conclusion, despair can only mean attack.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/ten-theses-trump-vocabulary/