Computed Conformity

Not only do our devices know our deepest desires, they also reprogram what we want and how we go about getting it — keeping us to conformist paths.

Algorithmic Control and the Revolution of Desire

- Issue #4

- Author

Last year, Stanford University published a study confirming what many of us may long have suspected: that your computer can predict what you want with more accuracy than your spouse or your friends. Your digital footprint betrays the truth not only about what you “like” but about what you really like — or so the argument goes. But what if our digital footprints, besides revealing our desires, are also responsible for the very construction of these desires? If that were the case, we would need to display a far deeper level of suspicion towards the complex patterns of corporate and state control found in contemporary cyberspace.

There is little doubt that innovations in mobile technologies are part of emerging methodologies of social control. In particular, games and applications that make use of the Google Maps back-end system — including Uber, Grindr, Pokémon Go and hundreds of others — which should be seen as one of the most important technological developments of the last decade or so, are particularly complicit in these new regulatory practices. Putting the well-publicized data collection issue aside, such applications have two powerful ideological functions. First, they construct the new “geographical contours” of the city, regulating the paths we take and mapping the city in the service of both corporate interest and the prevention of uprisings. Second, and more unconsciously, they enact what Jean-Francois Lyotard once called the “desirevolution” — an evolution and revolution of desire, in which that what we want is itself now determined by the digital paths we tread.

The Psycho-Geographical Contours of the City

In 1981, the French theorist Guy Debord famously wrote of the “psycho-geographical contours” of the city that govern the routes we take, even when we may feel we are wandering freely around the physical space. At that time, it was Debord’s topic — architecture — that was the dominant force in re-organizing our routes through the city. Today, however, that role is increasingly taken up by the mobile phone. It is Uber that dictates the path of your taxi, Maps that dictates the route of your walks and drives, and Pokémon Go that (for a summer at least) determined where the next crowd would gather.

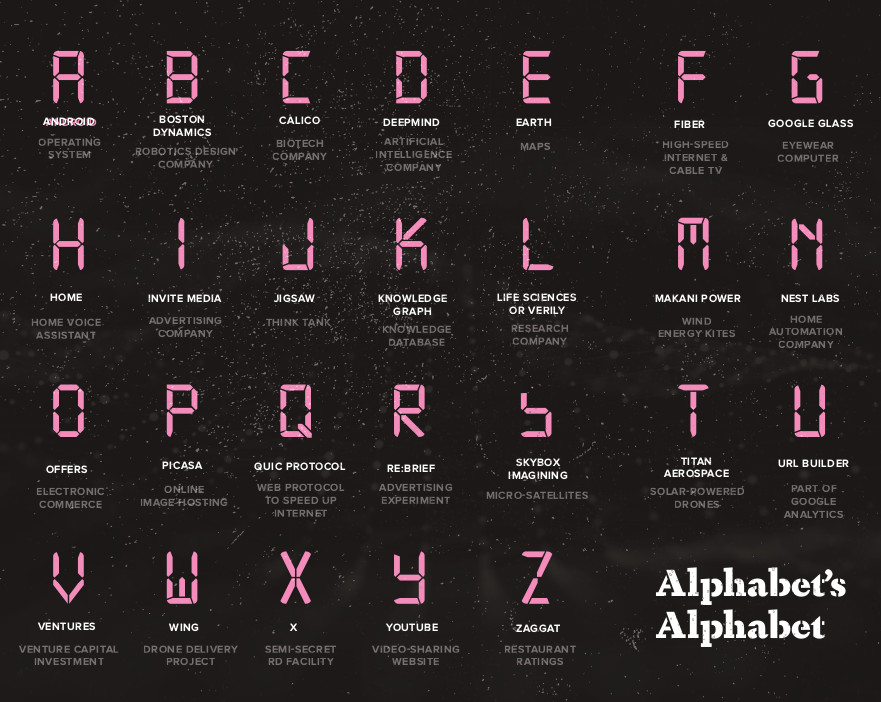

Other similar map-based application programing interfaces, or APIs, dictate our jogging routes (MapMyRun), our recreational hikes (LiveTrekker) and our tourist activities (TripAdvisor Guides). Pokémon Go attracted some publicity because it accidentally and humorously gathered crowds in weird places, but this should only alert us to its potential ability to gather crowds in the right places (to serve corporate interest) or to prevent the gathering of crowds in the wrong ones (to prevent organized uprisings, for instance). Such applications should be seen as a testing phase in the project of Google and its affiliated corporations as they work out how best to regulate the movements of large populations via their phones. Pokémon Go players were the early cyborgs, complete with hiccups and malfunctions — a beta version of Google’s future human. These future humans will go where instructed.

Other similar map-based application programing interfaces, or APIs, dictate our jogging routes (MapMyRun), our recreational hikes (LiveTrekker) and our tourist activities (TripAdvisor Guides). Pokémon Go attracted some publicity because it accidentally and humorously gathered crowds in weird places, but this should only alert us to its potential ability to gather crowds in the right places (to serve corporate interest) or to prevent the gathering of crowds in the wrong ones (to prevent organized uprisings, for instance). Such applications should be seen as a testing phase in the project of Google and its affiliated corporations as they work out how best to regulate the movements of large populations via their phones. Pokémon Go players were the early cyborgs, complete with hiccups and malfunctions — a beta version of Google’s future human. These future humans will go where instructed.

On a smaller scale, this point can be seen in concrete terms with a case study of London. A recent Transport for London talk discussed the possibility of “gamifying” commuting. In order to facilitate this possibility, Transport for London have made the internet API and data streams used to monitor all London Transport vehicles open source and open access, in the hope that developers will build London-focused apps based around the public transport system, thus maximizing profit. One idea is that if a particular tube station is at risk of becoming clogged up due to other delays, TfL could give “in-game rewards” for people willing to use alternative routes and thus smooth out the jam.

While traffic jam prevention may not seem like evidence that we have arrived in the dystopia of total corporate and state control, it does actually reveal the dangerous potentiality in such technologies. It shows that the UK is not as far away from the “social credit” game system recently implemented in Beijing to rate each citizen’s trustworthiness and give them rewards for their dedication to the Chinese state. While the UK media reacted with shock to these innovations in Chinese app development, a closer look at the electronic structures of mapping and controlling our own movements shows that a similar framework is already in its development phase in London too. In the “smart city” of the future, it won’t just be traffic jams that are smoothed out. Any inefficient misuse or any occupation of public space deemed dangerous by the authorities can be specifically targeted.

The Corporate Surveillance State

When it comes to these developments in technology, state and corporate forces work more closely with each other than ever before — and much more closely than they are willing to admit. Srećko Horvat has pointed out the short distance between the creators of Pokémon Go and Hillary Clinton, despite her odd and unsolicited recent public claim that she didn’t know who made the game. Likewise, Julian Assange’s strangely under-discussed 2014 book When Google Met WikiLeaks showed the shocking proximity of Google chief Eric Schmidt and the Washington state apparatus. In terms of surveillance and the use of big data, it has become impossible to sustain the distinction between state control and the production of wealth, since the two have become so irrevocably intertwined. As such, old arguments that “it’s all just about money” need to be treated with greater suspicion, since major firms today are so closely tied to the state. Various aspects of state organization should likewise be considered equally suspect because of their corporate underpinnings.

Of course, when it comes to the mapping applications that promise to help us access the best quality objects of our desire with the greatest efficiency and the least cost, these tempting forces of joint corporate and state control are entered into willingly by participants. As such, they require something else in order to function in the all-consuming way that they do. Far from simply channeling and transforming our movements, they also need to channel and even transform our desires.

Of course, when it comes to the mapping applications that promise to help us access the best quality objects of our desire with the greatest efficiency and the least cost, these tempting forces of joint corporate and state control are entered into willingly by participants. As such, they require something else in order to function in the all-consuming way that they do. Far from simply channeling and transforming our movements, they also need to channel and even transform our desires.

We are now firmly within the world of the electronic object, where the mediation of everything from lovers and friends to meals and activities via our mobile phones and computers makes it virtually impossible to separate physical from electronic objectivity. Whilst the electronic Pokémon or the “in-game rewards” offered by many applications may not yet have the physicality of a lover who can be accessed via Tinder, or a burger that can be located via JustEat, the burger and the lover certainly have the electronic objectivity of the Pokémon. We can therefore see a transformation in the objects of desire taking place by and through our devices, so that we are confronted not only with a change in how we get what we want, but with a change in what we want in the first place.

Italo Calvino once wrote of the “amorous relationship” that “erases the lines between our bodies and sopa de frijoles, huachinango a la vera cruzana, and enchiladas.” While in such a moment food and lover become one in a kind of orgy of physical consumption, in the same novel Calvino warned of a time “when the olfactory alphabet, which made them so many words in a precious lexicon, is forgotten,” and in which “perfumes will be left speechless, inarticulate, illegible.”

It is this world that we find ourselves desiring in, where an orgy of electronic objects with no olfactory physicality blurs the distinction between lovers, meals and “in-game” rewards. The purpose of this shift, of course, is to increase the power of technological corporations by giving them a new sort of control over the way we relate to our objects of desire. If the boundaries between the way we search, desire and acquire our burgers, lovers and Pikachus are dissolving, it is not so much the old point that everything has become a commodity, but a new point that this kind of substitutional electronic objectivity endows corporate and state technologists with unprecedented power to distribute and redistribute the objects of the desire around the “smart city.”

Data Centralization in China and the West

There is, moreover, a significant centralization of power underpinning these developments. Like the social credit idea, the Chinese phenomenon of WeChat — developed in 2011 by Tencent, one of the largest internet and mobile media companies in the world — has received concerned media coverage in the West. WeChat is the first truly successful “SuperApp,” the basic premise of which is that all applications like WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, OpenRice, Tinder, TripAdvisor and many more, are rolled into one cohesive application. All for our convenience, of course.

As a result, however, there is now a new level of cohesion between the data-collection and movement monitoring going on in the mobile phone as a whole, where all data is now directly collected in a single place. More than half of the 1.1 billion WeChat users access the app over 10 times per day, and many users simply leave it on continuously, using it to map, shop, date and play. This means that the app sets a new precedent for continually monitoring the movements of a whole nation of citizens. WeChat’s incredibly strange “heat map” feature actually lets users — and authorities — see where crowds are forming. The claim is that this has nothing to do with crowd control: the objective is simply to help us access the least crowded shopping malls, doing nothing more than helping us get what we want.

WeChat is already the most popular social media application in China, but it will soon have huge significance worldwide, with an international version now available and many replica “SuperApps” in production. What the Western media finds to be so concerning about WeChat is once again something that already exists here in the West, at least in beta form, without us knowing it. WeChat actually offers us a glimpse into an Orwellian future in which companies and governments can track every movement we make. While in China the blocking of Google means that WeChat uses Baidu Maps as its API, the international version of WeChat simply taps into Google Maps, showing just how deeply integrated these corporate technologies already are.

What emerges from Western media coverage of these developments is the continued insistence on an apparent division between the public and the private sphere in the United States and Europe. When it comes to digital surveillance and the monitoring of movement, the situation is almost certainly better in the West than it is in China at this moment. Yet from an analysis of recent developments in China we learn not only that we need to be attentive to similar dangers here in the West, but also that there are powerful ideological mechanisms at play to obscure these developments by presenting China and the US as fundamentally opposed to one another. Whilst in China the links between the new SuperApps and the state are commonly accepted, in the US the illusion of privacy remains paramount. Although data is often shared between different corporations and between the public and the private sectors, this fact is generally obscured. The continued expressions of shock at the more openly centralized state control visible in China serve only to further consolidate the impression that these things are not happening in the US and Europe.

Furthermore, WeChat reveals more than the dangers of mass data collection and new levels of technological surveillance. It also embodies the power of the phone over the objects of desire. Since one single app can successfully market us food, lovers, holidays, events, blogs and even charities, the connections between such “objects” become more important than the differences. While the structural similarities between Grindr, Pokémon Go and OpenRice become apparent via analysis of both their surfaces and back systems, WeChat makes the connections plain to see. The various forms and objects of each individual’s desire no longer represent discreet and separable elements of a subject’s life. Instead we enter a fully cohesive libidinal economy in which we are increasingly regulated and mapped via the organization of what and how we desire.

The Desirevolution

So what do we do when faced with this revolution — a technological revolution that is not overthrowing any existing power structures but rather transforming the world in the service of private corporations and the state? Often, the response of those concerned by such developments is to express hostility or distrust towards technology itself. Yet to break this corporate organization of desire, we need not nostalgically yearn for a desire that is free of politics and technology, for no such desire is possible. On the contrary, what we need is to recognize that desire is necessarily and always controlled by both politics and technology.

This awareness would be the first step towards ensuring that the centralized corporate and state organization of desire malfunctions — and, ultimately, it would be the first step towards its potential reprogramming. The corporate desirevolution depends on our blindness to the politics of its technologies, asking us to experience our desires as spontaneous yearning and our mobile phone and its powerful apps as just tools for our convenience, helping us get what we want in the easiest way possible. We need to recognize that this is far from the case. The principal concern of those who own the apps — perhaps even more powerful than data collection — is to transform desire itself. At the very least, we can make visible the complicity of such technologies in producing the perfect conformist modern citizen.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/algorithmic-control-smartphone-internet-apps/

Next Magazine article

Neoliberalism’s Crumbling Democratic Façade

- Joris Leverink

- December 18, 2016

Mass Surveillance and “Smart Totalitarianism”

- Chris Spannos

- December 18, 2016