The cybernetics of Occupy: an anarchist perspective

- June 20, 2014

Anarchism & Autonomy

Stafford Beer’s organizational cybernetics can help us understand Occupy’s non-hierarchical democratic processes and the role of autonomy within them.

- Author

In 1963, in the British journal Anarchy, a short debate took place on the relationship between anarchist forms of organization and organizational cybernetics. Organizational cybernetics, for those unfamiliar with the term, is often defined as the science of communication and control in organic, mechanical and social systems. While the term might suggest images of high technology and even cyborgs, etymologically it is derived from the Ancient Greek word κυβερνήτης (kyvernítis, or kybernetes), which means ‘steersman’ or ‘pilot’, and referred to the steering of a ship.

The contemporary usage draws on this analogy in the sense that cybernetics is involved in identifying and studying the ways in which systems and organizations regulate (or steer) themselves through mechanisms of feedback and emphasizes the importance of lines of communication through which this feedback is received and actions are taken as a result. The element of control that cybernetics attempts to explain in systems is one of self-organization: a system regulates and manages itself and doesn’t require external influence in doing so.

The debate in Anarchy, between British cyberneticians William Grey Walter and John McEwan, focused on the application of early developments in this science to explain how self-organization works in the context of social systems. In other words, can the study of feedback, communication and self-regulation in biological and mechanical systems by applied to human social systems? One writer who took up this idea was the noted anarchist thinker Colin Ward.

Ward, the editor of the journal Anarchy, wrote an essay in 1966 titled ‘Anarchism as a Theory of Organization’ in which he elaborates on the dynamics of anarchist organization and emphasizes the connections between anarchism and organizational cybernetics. “Cybernetic theory,” he writes, “with its emphasis on self-organizing systems, and speculation about the ultimate social effects of automation, leads in a similar revolutionary direction” as anarchism (John Duda presents a brilliant analysis of the history of cybernetics and anarchism in an article published last year in the journal Anarchist Studies). Ward draws on the work of classical anarchist geographer Peter Kropotkin as well as on examples of non-hierarchical anarchist organization that take place in everyday life.

Some of the core features of anarchist organization, according to Ward, are (1) that collectives and groupings should be based on voluntary participation, (2) that they should be aimed at performing a specific function and (3) should temporarily exist only for as long as they perform that function, and (4) that they should be small and based on face-to-face contact between participants.

For Ward, these elements would go at least some of the way towards ensuring the non-hierarchical nature of these forms of organization. Functions requiring larger organizational efforts ought to be met not by fixed structures but by federations in which “large-scale functions can be broken down into functions capable of being organized by small functional groups.” In addition to this, Ward is keen to highlight the importance of autonomy within organizational forms, and it is in this that his account of organization comes closest to that of organizational cybernetics.

While research on cybernetics began during the Second World War and was properly formalized by Norbert Wiener (in his book Cybernetics: Or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, published in 1948) it is to a later cybernetician that I want to turn in identifying the similarities between organizational cybernetics and anarchism. Stafford Beer developed his account of cybernetics while working in the steel industry in the UK in the 1950s. Despite little formal education in engineering, mathematics or other sciences, Beer made a name for himself internationally with the publication of Cybernetics and Management in 1959.

Project Cybernsyn

It was on the basis of this book that he was invited in 1970 to assist Salvador Allende’s newly-elected socialist government modernize and rationalize the Chilean economy. Thus followed arguably the most important period in the development of cybernetics as Project Cybersyn, as it became known, brought together the political principles of Allende’s government with Beer’s approach to effective organization. Central to the whole process was autonomy: the autonomy of different parts of the economy (factories and other enterprises), networked together using telex machines and a single central computer used for processing information received from these individual parts.

While the project was cut short by the US-backed coup in September 1973, the application of organizational cybernetics to the problems of communication and self-regulation in the Chilean economy had some remarkable successes during its short life (Eden Medina’s book Cybernetic Revolutionaries provides the whole story of the Chilean experience with cybernetics and is perhaps the most accessible and enjoyable books on cybernetics available).

The period Beer spent in Chile radicalized him politically, leading to him virtually renouncing the materialism of the upper-middle class lifestyle he had become accustomed to and eventually moving to a remote cottage in Wales that lacked electricity and running water. As Ward and other anarchists correctly identified, a potentially radical conception of autonomy and self-organization does lie at the center of organizational cybernetics and its account of effective organization.

Beer’s early work, prior to his experience in Chile and written as it was in the 1950s and ’60s, focuses on industrial production, and he shows that in organizations where different units (i.e. those concerned with producing separate components or those involved in different tasks like sales and manufacture) have the autonomy to work according to their own directives — based on their unique knowledge of what is required within their niches — a level of internal stability and effectiveness is reached which is difficult if not impossible in organizations where a strict, top-down hierarchy permeates every action of the workers at the bottom of the chain of command.

Coordination is achieved by communication between units working in different niches rather than through centralized control. Beer basically opposes Taylorist scientific management with a call for granting autonomy to the individual parts of an organization. To be sure, the autonomy is limited within the overall plan of the organization, which is decided at a senior management level (in the Chilean case this relied on a social democratic account of parliamentary authority), but the role of autonomy, and the potential of what Beer called the Viable Systems Model holds for genuinely democratic and anarchist organization, is nonetheless fascinating.

The Viable Systems Model is based on a tiered conception of an organization in which different tiers or levels are responsible for different functions ranging from ground-level operations to facilitating communication between different operations to decision-making about the strategic goals of the organization. Beer’s classic model, presented in his 1972 book The Brain of the Firm, assumes that while those at the bottom of the organization, the individual operational units, should be granted autonomy to work in their niches as they see fit. Higher level activities such as determining strategy should however be undertaken by a group of trained managers, separate from the workers on the shop floor.

Following the success and ultimate untimely demise of Project Cybersyn in Chile, Beer pushed the democratic character of the Viable Systems Model further by arguing that there should be mechanisms in place through which those at the bottom of an organization are able to influence policy at the top. Indeed his recommendations are not dissimilar to those proposed by proponents of E-democracy today. It is in the radically democratic character of anarchist organization, however, that the Viable Systems Model can be pushed to its furthest logical conclusion in terms of politics.

As anarchists like Ward and McEwan highlighted, by insisting that the different levels in the organization be seen as functions into which different individuals can step at different times, rather than as fixed offices, those involved in the day-to-day operations of the organization can be the very same people involved in strategic decision-making and other levels of the organization. The autonomy in this more radical version of the Viable Systems Model is extended to include not just operational issues but all aspects of the organization.

In this way Beer’s politicization of organizational cybernetics can be taken in an even more radical direction and can form the basis for understanding the dynamics of effective and stable democratic organization. Crucially, the autonomy embedded in the Viable Systems Model takes on a dual role as an essential part of an effective system and as a practical outworking of anarchist political ideals.

Turning to more recent examples of radical and anarchist organization, the general structure of this type of Viable Systems Model can be clearly seen. To elaborate on this, I want to take the example of the Occupy movement, and while what I’m presenting is an ideal account of how Occupy camps were organized, it serves to show the potential in this organizational form (which was common to much of the uprisings that occurred in 2011 and after) for a genuinely non-hierarchical, anarchist politics.

The Cybernetics of Occupy

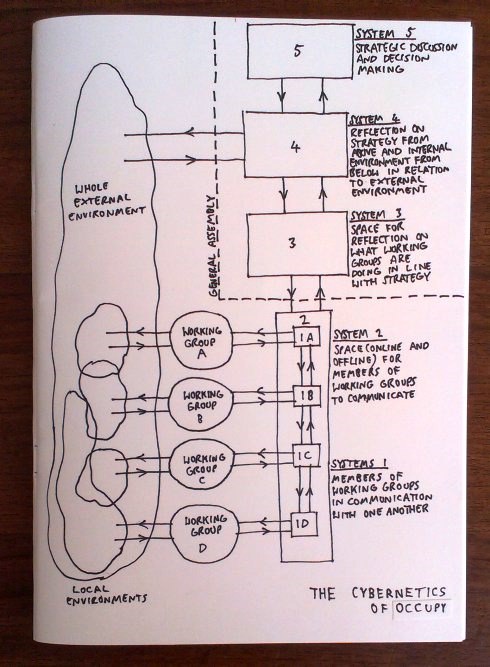

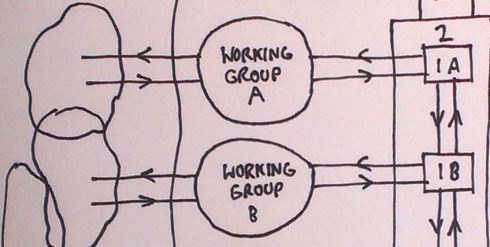

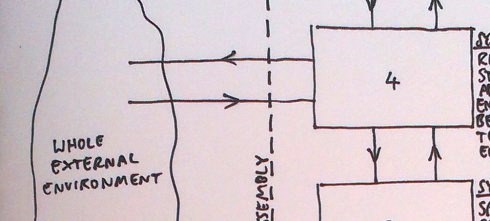

The Viable Systems Model is composed of five layers or systems. In addition to these five layers there are the operating units of the organization (in the case of the Occupy example, working groups) and the environments in which they operate, some overlapping and others not, as well as the whole environment in which the organization or system exists. The overall goal of organizational cybernetics is to show how an organization can achieve its aims while remaining internally stable.

System 1:

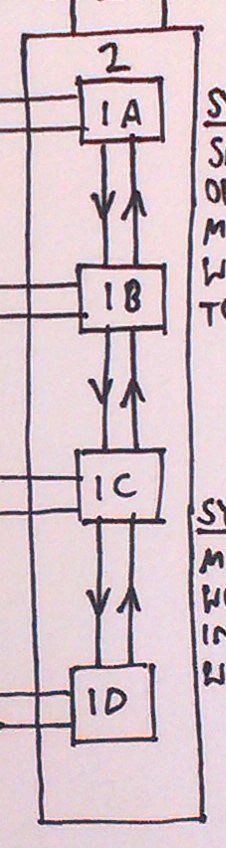

The blocks lab elled 1A, 1B, etc. in the diagram above represent the members of working groups in communication with one another. While in Beer’s account of the firm these are middle managers or foremen who both formally and informally shout across the void, as he puts it, in this modelling of the ideal Occupy camp these can be any member of a working group in communication with any other. There aren’t any specific roles at this level of the organization. The importance of this level of communication is basically to make working groups aware of what the others are doing, so that autonomous activities can be coordinated in an informal way.

elled 1A, 1B, etc. in the diagram above represent the members of working groups in communication with one another. While in Beer’s account of the firm these are middle managers or foremen who both formally and informally shout across the void, as he puts it, in this modelling of the ideal Occupy camp these can be any member of a working group in communication with any other. There aren’t any specific roles at this level of the organization. The importance of this level of communication is basically to make working groups aware of what the others are doing, so that autonomous activities can be coordinated in an informal way.

System 2:

System 2 in the diagram envelops systems 1 within it. This is to represent the formal space in which the communications between working groups take place. It could be either the physical space of the camp itself or the online spaces created on various social networking platforms.

System 3:

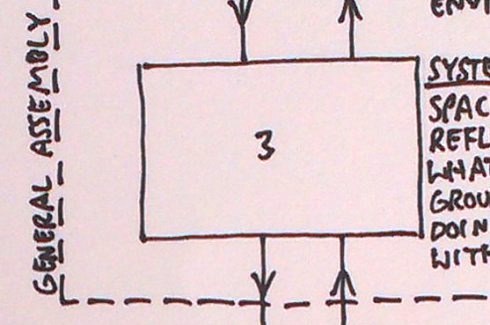

The third level of the model aims to allow members of the organization to reflect on the activities of the working groups in relation to the overall strategy of the organization as a whole. Discussions at this level would take place during the General Assemblies that came to symbolize Occupy’s decision-making structure. This allows the members of the working groups to consider their activities and adjust them if necessary in line with the decided-upon goals of the org anization.

anization.

For Occupy this is crucial as at this level the people engaging in the discussions are not separate or distinct from those involved in the working groups. The same individuals step out of their functional role as working group members and into that of reflecting on their practice within working groups. This is an essential distinction in the anarchist form of viable system developed here: there is a hierarchy in terms of function but not in terms of structure and it is not a hierarchy that issues commands from one group to another group. Rather, decisions are made democratically by all members of the organization. Limits are imposed on their autonomy but these are limits that are agreed upon together.

System 4:

System 4 involves the same individuals again, and also the General Assemblies, reflec ting on the activities of the working groups and the organization as a whole as well as its overall strategy in relation to events in the outside world. System 4 has a view to the tactical activities of lower levels in the model, strategic decisions made at the higher fifth level and the external environment in which the organization exists. This allows for adjustments to both tactics and strategy in light of changes in the environment that individual working groups might not be aware of. Again, for Occupy the distinction is functional and the activities of System 4 would involve all members of the organization discussing together at General Assemblies.

ting on the activities of the working groups and the organization as a whole as well as its overall strategy in relation to events in the outside world. System 4 has a view to the tactical activities of lower levels in the model, strategic decisions made at the higher fifth level and the external environment in which the organization exists. This allows for adjustments to both tactics and strategy in light of changes in the environment that individual working groups might not be aware of. Again, for Occupy the distinction is functional and the activities of System 4 would involve all members of the organization discussing together at General Assemblies.

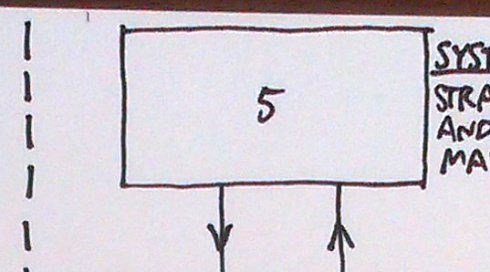

System 5:

The final level of the model of Occupy I’m presenting here is that which is concerned with the strategy and overall goals of the or ganization as a whole. This is again a level of discussion and decision-making that is, or should be, open to all in the organization. It is where decisions are made about the objectives and priorities of the organization and is ultimately what limits the autonomy of the working groups; but again, this is not a limitation coming from a distinct group of leaders but is something that is agreed upon democratically by all members of the organization.

ganization as a whole. This is again a level of discussion and decision-making that is, or should be, open to all in the organization. It is where decisions are made about the objectives and priorities of the organization and is ultimately what limits the autonomy of the working groups; but again, this is not a limitation coming from a distinct group of leaders but is something that is agreed upon democratically by all members of the organization.

In addition to these five levels within this ideal model of the Occupy camp, there are of course the flows of information that are represented by the lines with arrows. These highlight how information flows through the organization, between the different functional levels and to and from the external environment.

Diagnosing Occupy

What this representation of Occupy as a viable organizational cybernetic system allows is not only an understanding of how things went well for the 2011 uprisings and similar experiences that, in one way or another, adopted a broadly anarchist form of organization (Not An Alternative’s critique of Occupy in fact reinforces the importance of autonomy within its structure), but also crucially where and why things went wrong. Mark Bray, for example, in a recent article on the failures of Occupy, identifies the divergent strategies between liberals and radicals in terms of the role of the individual within the collective.

According to the model presented here, this comes down to a difference in strategy at System 5, which in turn provides differing messages to working groups in terms of the limits to their autonomy and their role in the organization. Without a clearly agreed upon strategy, individuals and groups operate along different lines and in often conflicting and mutually-detrimental ways. Agreement at System 5 allows for a clear paradigm in which to work and creates a clear objective for the organization and gives working groups the strategic perspective they need in order to effectively work autonomously within their own niches.

While using Stafford Beer’s organizational cybernetics to explain the successes and failures of Occupy undoubtedly misses out a lot of the analysis, its focus on levels of action and decision-making as well as on the lines of communication and flows of information can, I believe, help in understanding some of what was going on at an organizational level. The modifications to the model to account for the radical democratic processes put to work in Occupy and other uprisings are important in providing for a greater understanding of non-hierarchical organization and the role of autonomy and functional hierarchy within them.

The working group structure of Occupy, combined with the space for strategic decision-making in the General Assemblies, made possible the kind of anarchist organization Colin Ward discussed in his 1966 essay. Working groups engaged functionally in different niches and, as a cybernetic analysis makes clear, were able to do so with a level of autonomy that was limited not by a hierarchical command structure but by decisions made by the very same individuals at the General Assemblies.

The relationship between working groups, as represented in the anarchist version of the Viable Systems Model sketched here, mirrors in many ways that of the anarchist federation. Indeed, viewing the Occupy movement through the lens of the work of Stafford Beer in organizational cybernetics helps bring out the anarchist characteristics of this as a form of effective and at the same time radically democratic organization.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/cybernetics-occupy-anarchism-stafford-beer/