Beyond the Hashtags? Gezi and the AKP’s Media Power

- January 11, 2014

Authority & Abolition

The alternative media practices used in the Gezi uprising have changed the political parameters and may yet create real institutions of popular power.

- Author

When a group of environmental activists sought to defend one of the only green areas in downtown Istanbul from being turned into a shopping mall on May 30, 2013, little did they know that their protest would spiral into the most serious popular uprising in modern Turkish history. Activists used social media like Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr as the mainstream media failed to report their actions and the violent police crackdown. Activists and supporters went beyond the use of hashtags in order to undermine Erdoğan’s AKP and create radical alternatives from below. In Turkey, this has sparked people’s imagination and will help fire up their actions next time around. For us abroad, it should reconfigure how we look at activists’ use of social media.

Will the Revolution be Tweeted?

During the media black-out in the first couple of days, activists and supporters of the blossoming Gezi movement turned towards corporate-owned social media such as Twitter for news on what was happening. Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook became practical tools for activists to render their actions and the police repression visible to fellow protesters in Turkey, international activists and sympathizers abroad, and a general news audience around the world.

A few days into the Gezi revolt, the New York University’s Social Media and Participation Lab released a report titled ‘A Breakout Role for Twitter? The Role of Social Media in the Turkish Protests’. It shows that more than during the first two days, 90% of all recorded Tweets on Gezi came from within Turkey and 50% from within greater Istanbul. The hashtag #OccupyGezi was mentioned more than 160.000 times on the first day alone.

By the following day, the Lab had collected and mapped more than two million tweets containing the hashtag #OccupyGezi. The quantity of Tweets collected and mapped is of unprecedented scale. However, the collection of Tweets does not tell us anything about how individual activists and movement participants used new communications technologies such as Twitter; or how new forms of collective action developed through the use of Twitter and other social media. In fact, the study reinforces the orientalist prejudice that social movements in faraway lands can only be successful if they make use of Western technologies.

In his book, Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism, Paolo Gerbaudo argues that the indignados in Spain and Occupy activists in the United States used Twitter primarily as a “means for internal coordination” between activists, and Facebook as a “recruitment platform” where activists could enlist non-political contacts such as friends and family to their cause. Communications researchers Miriyam Aouragh and Anne Alexander argue that Egyptian activists used social networks such as Twitter and Facebook as “tools of mobilization” and “spaces of dissidence” during the February revolution of 2011.

These theorists provide possible explanations as to how activists might have used social media and the internet during the Gezi protests. Unfortunately they fall into the same trap as the above mentioned study as they confine themselves to the analysis of social media without accounting for the national media environment that activists are embedded in, as well as the different media technologies and formats they make use of in the same round of mobilization (and, even the same demonstration).

This is exemplified by a YouTube video of a Turkish Airlines cabin crew on strike. The video underlines how activists consciously mediate themselves in front of different audiences to build new coalitions and bonds of solidarity. With their faces hidden behind the Guy Fawkes/Anonymous masks — the symbol of the new wave of anti-capitalist protest since Occupy — they are lined up in a dance-formation in front of the Turkish Airlines headquarters in Galata.

Rather than performing a dance routine, the female strikers subvert the usual safety announcement conducted at the beginning of each flight. They condemn the media for not covering their dispute and go through a list of grievances before fastening their seat belts — around their necks, thus creating a noose to hang themselves. This is culture-jamming at its finest, coming from a group of workers who traditionally vote for Erdoğan’s AKP.

Beyond the Hashtag

Based on my own online observations, which involved watching countless hours of Youtube footage and discussions with activists who participated in the Gezi protests, I argue that #OccupyGezi should reconfigure our thinking on how activists use (social) media. The activists of the Gezi commune used a variety of different tactics and strategies to strengthen their movement and counter the media black-out. They subverted Prime Minister Erdoğan’s denunciation of the movement as looters (çapulcu) and turned it into a collective identity by integrating the English neologism ‘chapuller’ into their Facebook names and Twitter handles so that even Noam Chomsky declared himself “a chapuller” in solidarity on Youtube.

The popular humor and satire magazine Penguen became an amplifier for the movement by featuring many anti-governmental cartoons on its pages. Penguen also highlights to what extent the online world and the offline world are inter-related in contemporary social movements. The famous Twitpics of the “girl in the red dress” and the woman with open arms being blasted by water cannon appeared in cartoonified versions on the magazine’s front pages. Meanwhile the movement on the streets advanced qualitatively when it adopted the penguin as its symbol of resistance after CNNTurk aired the now infamous documentary. And one night scanning the internet I came across the Portuguese trade union confederation’s (CGTP) mobilization video of a group of penguins who act together to beat a killer whale gone viral in the new Turkish context.

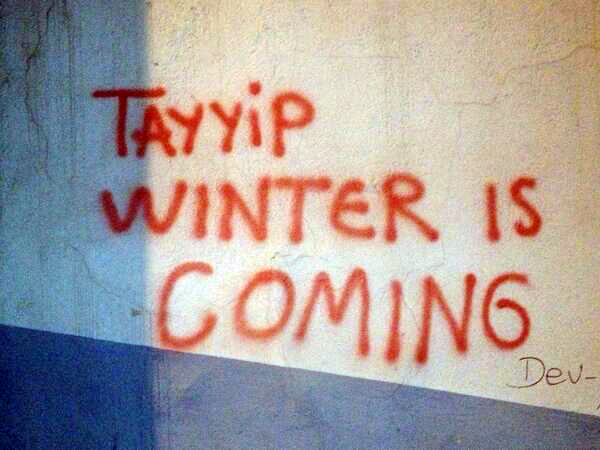

While protesters adopted humor, satire and subversion, Prime Minister Erdoğan continued a confrontational course both in form and content. An image which floated on Facebook showed an army of penguins with the text: “Tayyip – Winter is coming.” Again, Penguen took it up and turned it into a front cover. This Game of Thrones reference came after Erdoğan said: “We already have a spring in Turkey … but there are those who want to turn this spring into winter … Be calm, this will all pass.”

Erdoğan’s televised speeches and one-man rallies could not compete with the anti-systemic forms of communication that the movement adopted from the very first day. Thus the threats to shut down Hayat TV and to fine Halk and Ulusal TV for livestreaming protests exposed his desperation in face of an ever-growing movement on the streets. After President Abdullah Gül had praised the role of social media during the Arab Spring, Tayyip Erdoğan called Twitter and social media “the greatest menace to society” — despite having two million Twitter followers himself. In response, confrontational methods such as the RedHack Collective’s shutting down of the police’s webpage and the vandalizing of ntv vans caught the popular imagination.

As tear gas replaced oxygen in the streets, cooking shows, dance performances and popular soap operas filled the airwaves. While for our Turkish sisters and brothers a whole world changed in the first three days of the Gezi protests, the Turkish mainstream media continued with business as usual. For example, Sabah newspaper did not feature the protests on its front page in the first three days. Instead they showed President Abdullah Gül with a horse on a visit in Turkmenistan.

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

In order to understand the relationships between the media black-out, Erdoğan’s confrontational course and the activists’ (digital) media practices, one has to look at how Turkey’s neoliberal turn has concentrated media power into the hands of the few, in turn undermining the quality of Turkish democracy.

Turkey’s neoliberal turn preceded the AKP’s rise to power, yet the two are closely tied up with one another. In the 1990s, general elections were won or lost in the pages of Hurriyet and Sabah, which battled on behalf of the two main political parties, the CHP and the AKP’s predecessor, the Motherland Party. Once elected to government in 2002, the AKP sought to consolidate its power in the fragmented country. Tayyip Erdoğan’s son-in-law, the CEO of Calik Holding bought Sabah newspaper. Other businessmen-turned-media-moguls followed suit. They became either friends or foes in Erdoğan’s Turkey.

In 2008, the Prime Minister called for the boycott of The Doğan Media Group which controls Hurriyet; a confrontational course continued during the Gezi protests. Under the conditions of political polarization and increased economic pressure to produce shareholder value, channels such as ntv of the Doğuş Media Group moved closer to the AKP in years to follow. Other capitalist entrepreneurs such as the Demirören Group, which controlled 15% of the domestic oil and gas market, diversified their business by buying the up-market Milliyet daily newspaper in 2012. It was only during the media black-out that the popular classes started to comprehend that the media did not serve anyone’s interest but their own, and started turning to social media and alternative ways to communicate their message.

A by-product of this concentration of media power is the newfound fame of Turkish soap operas across Europe and the Middle East. Even in crisis-ridden neighbor country Greece they have gained widespread popularity. ‘Soft power’ is exclusively used to improve Turkey’s image abroad. At the home front, the Turkish people have to learn the hard way what Erdoğan’s hegemony and a neoliberal media ecology means in practice. Before the Kurdish-Turkish peace process, Erdoğan’s AKP made extensive use of anti-terror laws to imprison and sanction journalists, in particular those associated with the Kurdish cause. Today many remain in jail. According to independent reports more journalists are imprisoned in Turkey than in countries such as China or Belarus.

Before the Gezi protests shook Turkey, Erdoğan had seemingly learned how to move from seeking consent to coercion in order to maintain his hegemony and expand the neoliberal project to new areas of social life. One would imagine that the house of cards quickly came crashing down when a couple of environmentalists and activists unexpectedly connected to millions of ordinary people. The media’s response to the movement mirrored the experience of millions of Kurdish people whose protests had never been reported by the media.

In the days that followed, even respected journalists who had played by the rules found themselves under attack, like Can Dündar, who found his column pulled from Milliyet. Yavuz Baydar was sacked from his editorial position at Sabah newspaper for his ‘critical’ line on the Gezi protests. #OccupyGezi exposed the links between the Erdoğan government and the media moguls but the AKP’s triumphant neoliberalism would require more to crack.

From Movement to Change

From Movement to Change

Many of my contacts in Turkey have told me that things have reverted back to normal these days. It might even be argued that Erdoğan emerged stronger from of the uprising. However, the cracks at the top of Turkish society are exacerbated by widespread discontent from below. The fact that socialist feminists, anti-capitalist Muslims, CHP (Kemalists), the BDP, environmental groups and Football Ultras demonstrated and fought on the barricades together is unprecedented. While Gezi may not have had the power to dethrone Erdoğan and the AKP, the movement’s innovative media practices in a neoliberal media environment showed that the Gezi protests changed the parameters of Turkish politics while it lasted.

One would believe that such a coalition would suffice to break a government. However it may be precisely because activists from different political, ideological and religious backgrounds found themselves together for the very first time that they had a lot to learn. These lessons will not be in vein. The alternative practices established during the Gezi days have been engrained into the collective consciousness of those who participated in the protests. The uprising thus changed the parameters once and for all. Neighborhood assemblies and internet television channels such as ChapulTV can turn this broad coalition into a real movement that will not only see the BBC World Service end its collaboration with ntv, but that will create its own institutions of popular power.

I am indebted to a number of friends for always being there to answer my latest questions on Turkey over the last years. While we might disagree over a number of things, my writings and research on Turkey have greatly benefited from our debates and discussions both on- and offline. In particular, I would like to thank Ipek D., Nese K., Defne K., Cavidan S., Taylan H., Ege, Seda A., and Irem A.. This piece is dedicated to all of you!

This essay is part of the first ROAR symposium: ‘Reflections on the Gezi Uprising.’

1. Editorial

Gezi and the Spirit of Revolt

2. Rüzgar Akhat

Gezi: Losing the Fear, Living the Dream

3. Dilan Koese

Revolt of Dignity: Gezi and the Global Legitimation Crisis

4. Burak Kose

The Culmination of Resistance Against Urban Neoliberalism

5. David Selim Sayers

Gezi Spirit: The Possibility of an Impossibility

6. Cagla Aykac

Strong Bodies, Dirty Shoes: An Ode to the Resistance

7. Stephen Snyder

Gezi Park and the Transformative Power of Art

8. ROAR Collective

The Sultan Is Watching: Erdoğan’s Lust for Power

9. Yasemin Acar & Melis Ulug

The Body Politicized: The Visibility of Women at Gezi

10. Elif Genc

At Gezi, a Common Voice Against State Brutality

11. Erkan Gursel

Sarisuluk’s Story: A Family Fighting for Justice

12. Beatrice White

Cracking Down on the Press: Turkish Media after Gezi

13. Matze Kasper

To Survive, the Gezi Movement Will Have to Compromise

14. Mark Bergfeld

Beyond the Hashtags? Gezi and the AKP’s Media Power

15. Emrah Güler

Is Social Media Still the Way to Resist in Turkey?

16. Lou Zucker

Reclaim the Urban Commons: Istanbul’s First Squat

17. Christopher Patz

From Madrid to Istanbul: Occupying Public Space

18. Sinan Eden

The Mayonnaise Effect: International Inspiration from Gezi

19. Mehmet Döşemeci

Superman, Clark Kent, and the Limits of the Gezi Uprising

20. Editorial

Beyond Gezi: What Future for the Movement?

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/occupy-gezi-social-media/

Further reading

To Survive, the Movement Will Have to Compromise

- Matze Kasper

- January 11, 2014