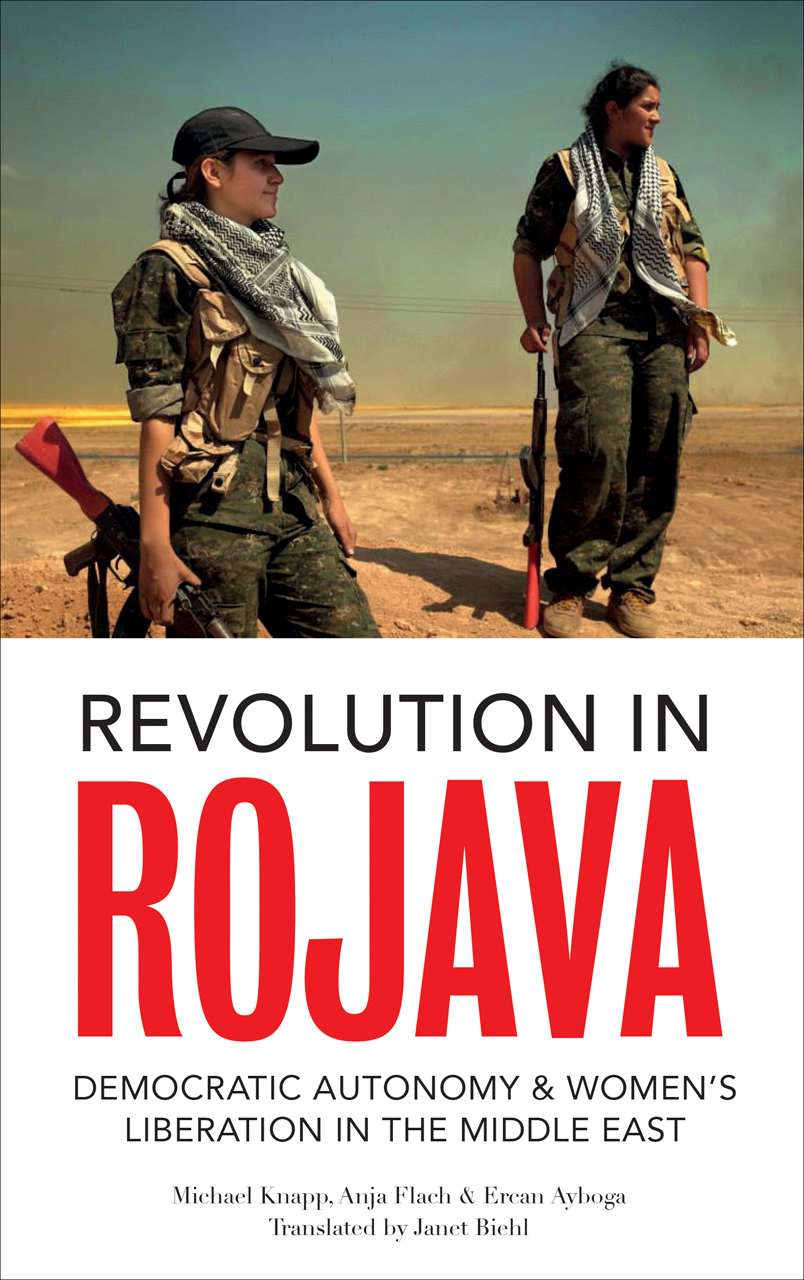

Photo: Kurdishstruggle

The revolution in Rojava: an eyewitness account

- October 20, 2016

Land & Liberation

An interview with the three authors of a new book — “Revolution in Rojava” — about their experiences and observations witnessing the birth of a new society.

- Authors

For decades, three million Syrian Kurds lived under severe repression by the Assad regime, their identity denied and access to education and jobs refused. Despite imprisonment and torture, the resistance grew. When the Arab Spring arrived in Syria, their organizations seized the moment to create a pioneering democratic revolution. The liberation of Rojava began in Kobane, on July 19, 2012. From this day on, the history of social and political revolution entered a new era.

Anja Flach, Ercan Ayboğa and Michel Knapp are longtime activists in the Kurdish freedom movement, working in Germany and Turkey. Together they visited Rojava in May 2014, and with their language skills, contacts and knowledge of the Kurdish movement, they were able to do close fieldwork for a full month. Upon their return, they compiled their observations into a book, Revolution in Rojava, published in German in March 2015. They have made subsequent visits to Rojava and updated the book. In its revised form, Revolution in Rojava is published in English by Pluto Press in October 2016.

Anja, Ercan, and Michel, your book is a deeply insightful contribution to understanding the Kurdish movement’s achievements in Rojava. First, please tell us a little about yourselves.

Anja: In the early 1990s I got to know the Kurdish women’s movement, and we formed a committee with Kurdish and German women. It deeply impressed me that many Kurdish activists saw no separation between the political and the personal, and that a women’s army was being created, of all places, in the Middle East. The German Left consisted almost entirely of students, but in the Kurdish movement, people from the whole population, from small children to the elderly, joined in demonstrations.

In 1994, I traveled to Kurdistan for the first time, with a delegation, to get to know the movement better and to learn from it. The Kurdish people’s determined struggle convinced me of the importance of the movement. In 1995, I participated for 2.5 years in the Kurdish guerrilla army. I wrote two books about the women’s movement, published only in German.

The next years were difficult. Öcalan was abducted and the Kurdish movement went into a deep crisis. In Hamburg, where I live, some other activists and I established a women’s council. At the moment I’m active in the women’s council, and I organize events and write articles. With German friends we discuss how we can implement the principles and methods of the Kurdish movement here in Europe.

Ercan: The Mesopotamian Ecology Movement was founded in 2011 as a network in North Kurdistan, when several ecological groups became active in different provinces. Since the beginning of 2015, it has been restructured as a social movement: in every province of North Kurdistan, it works in “ecology councils” of usually several dozen active members. The main work at the provincial level is carried out in up to twelve types of commissions.

The aim is to develop and strengthen the ecological character of the Kurdish freedom movement, as is the case with Kurdish women’s movement. We work against destructive and exploitative “investment” projects in rural and urban areas; we organize educational activities for political activists and for the general society; we develop projects around conservation, the use of local seeds and traditional construction methods; and we work with progressive municipalities for more ecological policies at the community level.

Michel, you live in Berlin and are the historian for the group and its geo-strategic analyst. What can you tell us about your Kurdish solidarity work?

Michel: Well, I actually come from the radical left-anarchist autonomous movement, but I had my first experiences with the Kurdish movement in the 1990s. I had been working in solidarity networks, but as anarchists we were critical of the Marxist-Leninist understanding of the PKK. Still, there was room for discussion and I was impressed by the PKK as the strongest left-wing movement in Germany. All other movements were in deep crisis due to breakdown of state socialism — even we anarchists.

We were all discussing “triple oppression,” and in that context the PKK’s definition of patriarchy as a central contradiction was really revolutionary for me. The development of democratic confederalism and its practice in North Kurdistan, which I had the opportunity to visit, left a deep impression. As a result I do not feel like somebody working in solidarity with, but rather as part of this movement for radical democracy — working in institutions like Civaka Azad, which is doing strategic analysis, conducting diplomacy, and organizing conferences; NAV-DEM, the Council System of the Kurdish Diaspora in Germany; and some solidarity networks like TATORT Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Solidarity Committee.

What made you decide to undertake that trip to Rojava in May 2014?

Anja: In 2013, as soon as I heard about the revolution in Rojava, I absolutely wanted to go there as soon as possible and study it and write about it. The journey couldn’t come together immediately, but I kept asking when it would be possible. A friend in the Kurdish movement then suggested that I write a book with Ercan and Michel.

Michel: Sure, the same as Anja. For me it was clear that I should go there because I had been working on Democratic Confederalism as an underground structure for quite a while, and now to see it in the open was a great opportunity. The first time I went to Rojava was in October 2013, and I got to know all the contradictions and all the propaganda being used to attack the Rojava project. So I wanted to see it with my own eyes, to learn from its practice, to understand the contradictions, and to research the difficulties. We can learn a lot from Rojava for revolutionary projects in Western countries.

Anja, what role have women played in the Rojava revolution? What are the women’s movement’s greatest achievements, in your view?

Anja: This revolution achieved international recognition because of the women’s units in Kobane — it surprised the world that women were commanders there and that they played a vanguard role in the revolution. But little was known about the Kurdish women’s army — it had existed since 1995 — and behind it stands a whole women’s system.

As early as the 1990s, women in Syria had developed an organization — not only in Rojava but also in Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and Raqqa. They went from house to house and established grassroots institutions under the umbrella of the women’s movement. In Rojava there is a women’s committee in every street, and in every neighborhood a women’s council, a women’s academy, women’s security forces, and armed units. No revolution can be successful if it lacks a female face. You cannot abolish capitalism without abolishing the state, and you can’t abolish the state without abolishing patriarchy.

In Rojava’s general society, many people still live under traditional gender structures. In what ways does the political women’s movement work to try to liberate women outside the movement, including non-Kurdish women?

Anja: The women’s movement would like to win over and organize every woman, regardless of whether she is a Kurd. Kongreya Star, the women’s umbrella organization, goes to every house. It is aware that the isolation of women from one another and competition among them is what gives power to patriarchy. Principles like dual leadership for every speaker position, and the 40 percent gender quota for every committee, had already been developed in the guerrilla army in the early 1990s, in order to roll back patriarchy.

Kurdish women have studied revolutions throughout the world closely and realized that in the past, after an armed struggle came to an end, women had to return to their traditional roles. That’s why they decided instead to create autonomous women’s structures in every area. If women create strong organizations, they can never be sent back to the kitchen. That included defense but also the economy. They can be independent only with an economic base. So in Rojava women’s cooperatives are being constructed everywhere.

These women are convinced that capitalism can be overcome only by a society based on non-patriarchal principles like communality, grassroots democracy, and an ecological economy. Syriac women are also starting to organize, to construct their own councils and military units. Arab women at the moment are still participating in the Kurdish women’s organization — they may need more time, but I’m sure they’ll eventually build their own organizations too.

The book presents the voices of many YPJ members. What is the continuity between the women’s forces that you observed in the mountains in the 1990s, and these young women?

Anja: In the 1990s in the mountains I got to know very strong women. One commander, Rûken, was one of the guerrilla leaders in Beytüssebab, North Kurdistan, despite the fact that she was only seventeen years old. She had no problems. Patriarchy in Kurdistan seemed to me to be very superficial, even among the nomadic asirets (tribes).

In Rojava I came across many of my onetime fellow fighters again. As young women they had left Rojava to join the PKK, and now they’ve returned to defend the revolution. For decades women in the PAJK, the women’s guerrilla army, have participated in political education. It’s part of everyday life to do political analyses, to read and discuss together, and to reflect on strategic matters. For several months each year, every woman participates in educational units.

These women have so much experience — they’ve read and discussed authors ranging from classical revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg to current thinkers like Maria Mies and Judith Butler. They’ve studied matriarchy, researched their own society, and almost at the same time put their new knowledge into practice. They analyze history from women’s viewpoint, because they’re convinced that one must understand the roots of society to change its future.

At the same time, the Kurdish movement is a youth movement — the older people transmit their experiences into collective life. Because the movement knows no hierarchy and privileges, everyone lives together and shares everything.

What surprised you most during your visit?

Anja: Visiting Rojava was like a dream come true. It was what we had been fighting for all those years — a free society that administers itself. The ideas of Abdullah Öcalan, which we had read about in books, were being implemented one by one. I had had doubts, but when I met my women friends again, their confidence was infectious. I was surprised by how many young people work voluntarily to carry on the revolution. Young girls work with the security forces, or in the city administration, seven days a week without payment. Women are everywhere and are part of everything.

It was also beautiful when my former commander Rûken took us to the front at Til Koçer. Here we met Arab men and women who had joined the YPG and YPJ. In the 1990s I had seen Turkish and Assyrian units in the mountains, but this dimension strongly impressed me — I heard young Arab women say, “We will become free women like the Kurdish women.”

Ercan, the book provides a clear and detailed description of the structure of communes and councils set up shortly before the 2012 liberation. Could you tell us the principles of this system? What are some of its challenges?

Ercan: The People’s Council of West Kurdistan (MGRK) and its coordination, the Democratic Society Movement (TEV-DEM), were initiated by the Democratic Union Party (PYD). After the uprising started in Syria, they undertook a broad self-organization of the Kurds in Rojava. The approach was to organize society and avoid armed clashes. The MGRK created a system of “radical democracy,” a combination of council and grassroots democracy.

On the ground are the communes, which are organized in the residential streets of cities and villages. Above them are the people’s councils at three other levels. Each of the lower levels is represented in the next higher level through its coordination. At all levels are nine commissions that cover areas like defense, women, civil society, diplomacy/politics, economy, education and health. This system has effectively empowered hundreds of thousands of people. People have started to govern themselves and to make decisions about their lives.

Together with the YPG/YPJ, the Rojava revolution started in July 2012, when the self-organized elements in society were strong enough and the Ba’ath regime quite weak. Later in January 2014, the MGRK initiated the Democratic-Autonomous Administration (DAA), which includes the vast majority of Rojava. Rojava consists of several ethnic and religious groups and many political parties. Although the DAA is a system of representative democracy, the MGRK system continues to exist and spread on the ground, particularly with the communes. A combined system called “democratic autonomy” has been working ever since in quite a successful way.

Is the MGRK system spreading into the areas newly liberated by the SDF? Are Arab villages, for example, adopting it, and perhaps other aspects of the revolution?

Ercan: Yes, the system is spreading into areas liberated by the SDF. TEV-DEM activists go the villages and cities and describe themselves and what they’ve done in the past few years. They propose that the people organize themselves in communes. At this stage there are no strong overarching organizational structures in these areas yet, but there are dozens of new communes, very soon hundreds of them, with a mainly Arab population.

In March 2016, the Federal System in Rojava/Northern Syria was declared, among other objectives, to encompass the liberated areas. But the name Rojava is Kurdish and refers only to Kurdish people, while the system is committed to including people of all ethnicities and religions. Recently, since we finished the book, discussions are underway about eliminating the name Rojava altogether and calling it the “Federation of Northern Syria.”

What are the principles of the new justice system in Rojava, in terms of arrests, criminality, conflicts and punishment?

Ercan: The first principle is that “crime” is mainly a result of unjust social relations and circumstances — it has political and social reasons. So in the discussions it is always asked why the person charged with an alleged “crime” might have committed it. Since the summer of 2015 this work has been done not only by the peace committees in the communes and neighborhoods, but also by the justice platforms, where up to 300 people may come together. A large group of people discuss the root causes of actions that are described as negative.

The peace committees solve problems at the lowest level, with the active participation of local people who are elected by the communes or people’s councils. As a result of the radical democracy, social and political justice in the whole society has been strengthened, and in the absence of repression by the state the number of prisoners has dramatically declined in general. In most of the cities there are a maximum of two dozen prisoners.

Are there political prisoners in the new society?

Ercan: Political prisoners do not exist, except fighters from terrorist organizations like ISIS or other Salafists. Several times members of political parties of the right-liberal bloc ENKS have been arrested in the context of political actions that were hostile, but all of them were released after few days. Sometimes ENKS members who have been arrested for nonpolitical reasons claim to be political prisoners. Almost all of them have been released. To date there is no evidence that prisoners or detainees have been tortured or even treated badly — several international human rights organizations have had unlimited access to all prisons.

What surprised you most when you visited Rojava?

Ercan: Several things, both positive and negative. In the Cizîre canton I could see no forests, not even a long line of trees, but instead unlimited fields of wheat. It expresses the loss not only of biological diversity but also of agricultural and human or cultural diversity. Another negative surprise was the dimension of the water crisis. All the rivers were dry — even in May — or else very polluted. The groundwater level was decreasing. Water scarcity limits life and production in many ways, and it poses a serious future challenge.

On the positive side, I was very impressed by the determination of the many political activists, including young people and women, that their struggle to overcome all challenges and their goal to build a new society would be successful. It gave me hope that the revolution will not be defeated, even though so many regional and international reactionary forces have strong interests in Syria.

Also very positive was the fact that there was no state anymore. You did not need to think that anybody might arrest you or that any intelligence service, police, camera or agent would be observing you. People with other political views are absolutely not a problem. You are free in Rojava!

Michel, the book contains a detailed account of Rojava’s “social economy,” based on cooperatives. Why did they choose this system? What kind of cooperatives did your group visit?

Michel: Many times when we asked friends in Rojava about that topic, they told us something like: “there can’t be real democracy without democratic control over all sectors of society, including the economy.”

The concept of a “social economy” was developed on the basis of Democratic Confederalism’s form of socialism, as distinguished from both neoliberalism and state-socialism. Their critique is that the development of the economy independently from society led to the establishment of exploitative states and finally to economic liberalism. In contrast, state socialism, which diverged from its own economic ideas, made the economy part of the state and turned everything over to the state. State capitalism isn’t very different from multinational firms, trusts and corporations.

In the social economy, production is to be administered neither by a state nor by the market but through the communes and the councils, which as institutions of self-representation are in a position to know the participants’ needs. While there is a market, the ideal of a communal economy projects its meaning to the exchange between councils. The cooperatives are connected through the councils’ economic commissions at all levels, and they should be able to fulfill the people’s needs for fuel, gas, flour, foodstuffs and other products of the communal economy. They are to build up federations to fulfill the needs of the population.

Cooperatives exist in all sectors of society, even the oil refinery sector. Most of the cooperatives we visited were small, with some five to ten members producing textiles, agricultural products and groceries, but there are some bigger cooperatives too, like a cooperative near Amûde that guarantees most of the subsistence for more than 2,000 households and is even able to sell on the market.

In a sense it’s an advantage for this process that the Syrian state treated Rojava as a classical colony. Resources were extracted but almost no production took place. To fulfill the demands of the people of Rojava, industrialization around ecological and communalist principles is being planned, but due to the war and the economic embargo, it hasn’t been realized yet.

Turkey would clearly like to extinguish the revolution, and indeed all Kurdish aspirations to autonomy, but so far it has failed to persuade the world that the PYD is a “terrorist” organization. In what other ways is Turkey working against the Rojava revolution?

Michel: There are many fronts and fault ines in the Middle East, and a third or fourth world war is raging in the region. Obviously there is a battle between Russia with its Shiite allies, and the West with its Sunni allies. But the situation is also more complicated as the so-called Islamic State is acting in many ways on its own. On the other hand, the federal system in northern Syria stands for democratization and for self-organization beyond statehood.

While analyzing the clashing alliances is quite useful when talking about Rojava, it’s important to also understand it as a war between statist powers and anti-statism: between capitalist modernity — of which ISIS is an expression — and the alternative: democratic modernity. This topic may seem theoretical, but it becomes clear when you look at the actions of the powers struggling on the ground. Enemies like Turkey and the Assad regime act together when it comes to fighting Rojava, and even the so-called allies of the coalition allow the incursion of Turkey into the region, intent on weakening the Rojava model.

Turkey itself is supporting extreme right-wing Turkmen militias and jihadist groups like Ahrar Al-Sham and Al Qaeda against Rojava. It is also directly attacking units of the YPG. The July 2015 massacre in Suruç of supporters of Kobane was perpetrated by ISIS suspects under Turkish surveillance. Jihadist militias terrorize the Kurdish population in North Kurdistan/Turkey as well as in Northern Syria and Iraq.

Turkey is also acting through the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) of South Kurdistan (Northern Iraq), which has its own proxies in Rojava called the ENKS, part of the so-called Syrian opposition under Turkish control. They’re waging war against the self-administration, especially in the Şêx Maqsûd neighborhood in Aleppo, including a propaganda war. They complain about their situation in Rojava, but they can still act freely in the region, even though they are affiliated with those attacking Şêx Maqsûd and have participated in numerous attacks on the self-administration.

Who are the best potential allies for Rojava’s federal system in the other parts of Syria?

Michel: The best allies for Rojava are the people, the revolutionaries worldwide — those who are struggling for emancipation and liberation. They are the strategic allies for the revolution. The people of Rojava are quite aware that statist and imperialist forces like the United States can only be tactical allies because their interest is contrary to social liberation and emancipation.

What surprised you most when you visited Rojava?

I have to state that the anti-propaganda had its influence on me, too. I came to Rojava and was so surprised to be able to visit everything, every opposition party — even parties that are radically against the self-administration. Prisons were open to us, and we were able to talk to the prisoners in private about their problems and their situation. People responsible for justice were discussing how one could build up a society without prisons.

One of my favorite parts of the book is the section on the Kurdish neighborhoods of Aleppo. The city lies outside Rojava itself, but democratic confederalism was implemented early there, even before the liberation of 2012, and the three cantons looked to Aleppo as a model for implementation. Now the horrific fighting between the government forces and the various jihadist groups of the opposition are reducing much of the city to rubble. Can you tell us anything about the Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo today? How are they surviving?

Ercan: Yes, in 2011 and 2012 the political structure in the mainly Kurdish-populated areas of Aleppo, especially the Şêx Maqsûd and Aşrafiye neighborhoods, was a model for the rest of Rojava. But since 2012 the three cantons have taken huge strides, and today “Free Aleppo” may have to look politically to them. At the end of 2014 fighters from Aleppo joined the heroic resistance at Kobane — a very interesting interaction.

Today only 20 percent of the original population live in Free Aleppo, under a very difficult situation. For one year there has been an embargo and daily attacks by Salafist and other reactionary groups. More than 170 civilians have been murdered in these neighborhoods alone. But the defense is quite strong; in the brutal war in Aleppo, it is on the side of neither the Syrian government nor the reactionary/Salafist armed organizations. The long-term aim is never to join either of them. The YPG/YPJ have lost almost no areas in recent years and have even liberated some small areas. The destruction is not as bad as in East Aleppo, where the majority of the buildings are uninhabitable.

The people live, cook, sleep and meet in the lower floors or in courtyards. Schools still work, and cooperatives have even been built up. But there is no centrally supplied electricity anymore, and diesel is very difficult to get. A big creative effort is requested to meet all basic needs.

Rojava’s revolution, now well into its fourth year, is surrounded by hostile forces from Turkey, the KDP in Iraq, and IS and other jihadists. Under these circumstances, its survival is remarkable. How do you explain it?

Anja: Rojava survives partly because the people have no alternative but to fight, and partly because of their organizations and their ideological background. The friends there have always said, Abdullah Öcalan lived and worked here for twenty years, it is the place where the most people have come in contact with his ideas. There are women here who have been doing grassroots work for thirty years. So the power vacuum opened up in the north because of the war, and the Kurdish movement was ready.

How can people elsewhere show solidarity and help it survive?

Anja: I think anyone who can make a contribution could go there directly. Especially doctors, midwives, engineers and others are urgently needed in Rojava. But a basic knowledge of Kurdish or Arabic is quite essential. Financial support is also very important, especially for the reconstruction and for the women’s institutions. There is a foundation [see sidenote] that builds women’s projects like cooperatives and kindergartens.

Political support for Rojava is very significant. The defense of Kobane has become a symbol of international solidarity. The attacks of Daesh [ISIS] between September 2014 und January 2015 almost wiped the city and canton of Kobane off the map. The YPJ and YPG fighters who defended it hardly had any heavy weapons and were able to hold the city despite self-sacrificing resistance for only a few days.

In Kobane many women’s units were at the front, and in the struggle against Daesh, they had sympathy on their side. If Kobane had not been held, the dream of the Rojava Revolution would have been over. That was clear to many progressive people around the world. Worldwide actions took place, which finally moved the United States to intervene and to support the YPJ and YPG against ISIS with airstrikes, which turned things around.

Finally, the international solidarity contributed a lot to preventing Kobane — and therefore Rojava — from falling into the hands of Daesh. Jarabulus, now under Turkish occupation, can be liberated only if pressure is raised against Turkey and all other states, like Europe, the US and Russia.

But the most important support would be to organize in our own countries and to take on the struggle against capitalist patriarchy. We can learn a lot from the revolution in Rojava. It is urgently necessary to organize and to construct an alternative to capitalist patriarchy. The survival of humankind depends on it, for war and industrialism — and the social and ecological disasters connected with it — are destroying the foundations of life. We don’t have much time left.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/revolution-rojava-pluto-book/