The solidarity ecosystems of occupied factories

- January 16, 2017

Work & Workers

The workers of the recuperated VIO.ME factory in Greece are building towards more supportive communities and a stronger, less-fractured society.

- Author

At first glance it is a factory: heavy machinery, crates, palettes, industrial barrels and men doing manual labor. Little catches the eye, except maybe the homemade banners hanging up around the warehouse. They’re in Greek, so you might not be able to read them, but you can tell these are not the stock decorations from the ‘IKEA industrial chic’ catalog.

Over a couple of days, you might also notice that you’re unlikely to see those men doing the same specific jobs, day after day, as you would in most factories. They seem to rotate their roles, mixing up batches of soap, pouring them into frames and cutting it into bars, but also cleaning toilets, taking product orders and coordinating distribution.

However, overall, when you walk into VIO.ME, it mostly looks like countless other industrial workplaces in the north of Greece and beyond. At least, until you come back on a Wednesday or a Thursday and find part of the administrative office converted into a free health clinic for workers and the wider community.

… or when you arrive first thing any day of the week and see all the workers gathered together, sharing updates on the work and making sure they are all in the know around the pertinent aspects of the business for the day ahead.

… or if you go into one of the store rooms and discover members of different migrant solidarity groups sorting through donations that are stored at the factory, for ongoing distribution around Thessaloniki’s many migrant squats, camps and occupations.

Over time, you notice that beneath VIO.ME’s sometimes mundane veneer, a series of radical changes are taking place. These are changes that offer alternatives to how we organize work, community and society at large. While VIO.ME has become a hallmark of these shifts in Europe, what those who work and support the factory are discovering is not unique. It is spreading, offering an alternative vision of how radical changes might occur in the ways we work, live and relate to the planet as a whole.

Introduction to workers’ control

Workers have formed cooperative workplaces together for at least three centuries. The recuperated workplace movement that the VIO.ME factory in Greece is a part of, however, traces its roots back to Argentina in 2001. This was a moment when the country was ravaged by neoliberal debt, frozen bank accounts and a handful of presidents who could only cling to the role for a number of days amidst mass public uprisings.

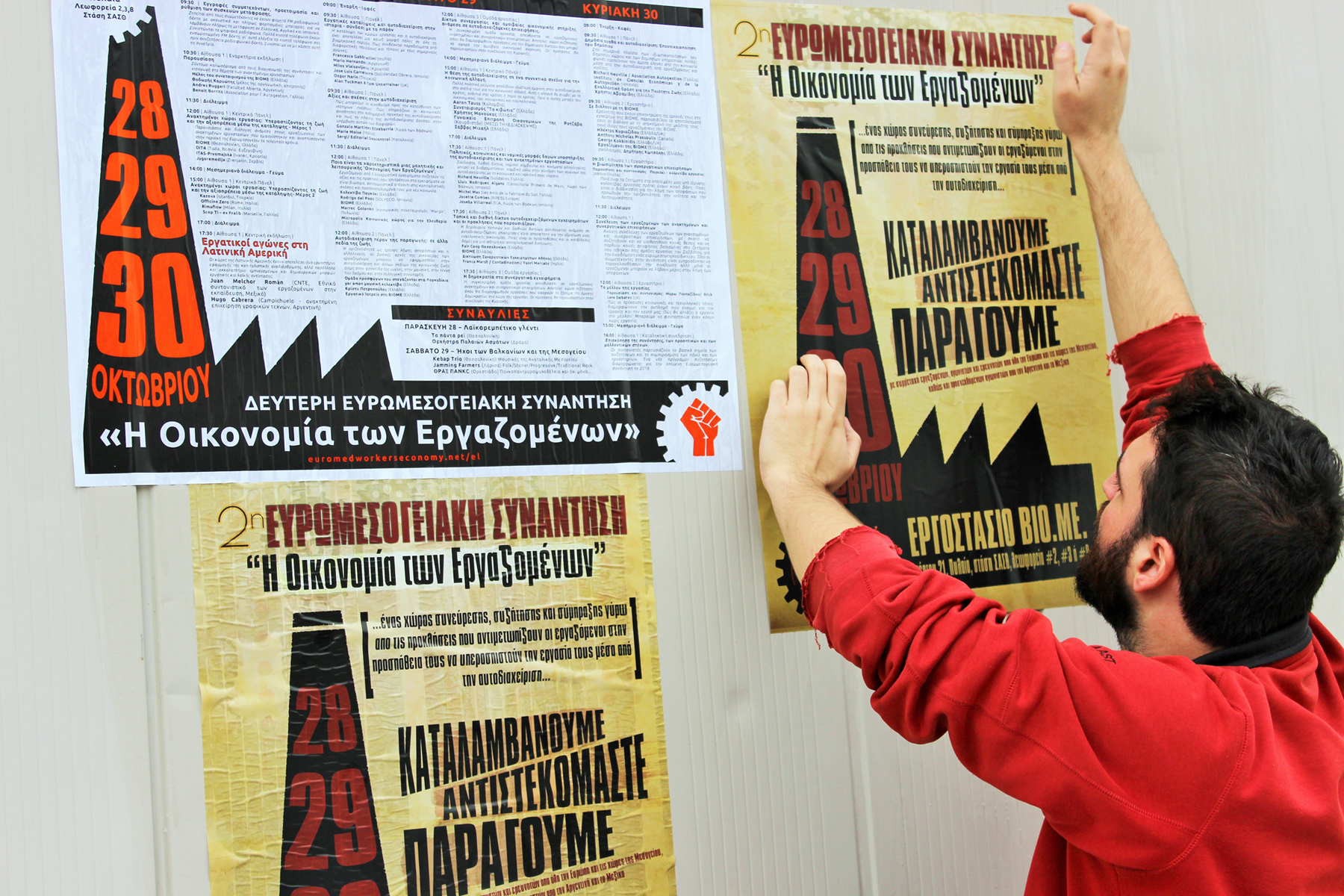

“It was an economic, political and social crisis,” says Andres Ruggeri, an academic at the University of Buenos Aires, who has been studying worker recuperations since 2002 and came to Greece to participate in the Second Euromediterranean Workers’ Economy meeting at VIO.ME in October. “This was not a working class, or middle class, or poor people’s insurrection — it was everything,” Ruggeri explains. “The ruling class collapsed. In this context, some of the bosses abandoned their factories.”

In 2001-’02, roughly one hundred workplaces that were left behind by their owners were quickly re-occupied by their workers. Though worker occupation was not a new phenomenon, its immediate explosion in Argentina at the turn of the millennium was the first time such actions had happened at this kind of scale.

Today in Argentina there are roughly 16,000 workers in 370 recuperated workplaces, holding up two fingers to the systems of work that have dominated the global economy since the Industrial Revolution. These coops range from industrial manufacturers, to hospitals, textile producers to chocolate factories, hotels to print shops. Some have come to lead their industries and have improved members’ incomes, making clear that it doesn’t take an MBA to run a complex business.

Though the movement has its roots in Argentina, it has spread across much of Latin America since the early 2000s, and begun to pop-up in countries around Europe, in the aftermath of the 2008 crash. VIO.ME is undoubtedly a shining star in the fledgling European movement for workers’ control, but similar projects to take back abandoned workplaces from absentee owners are currently underway in France, Italy, Serbia, Spain, Turkey, Croatia, Bosnia, and other parts of Greece.

While the motivations of the workers leading these occupations have been more pragmatic than utopian, what is emerging through their experiments is the DNA of a new kind of society.

How work changes, how change works

“We knew that if we left the factory, the economic crisis would leave us without money, with big problems with our families,” says Dmitri Koumatsioulis, one of the VIO.ME workers involved in the initial factory occupation in 2010. “We knew that we had to restart production without knowing the next steps.”

This was the uncertain footing from which the first steps were taken to put the Thessaloniki factory back to work after its bosses disappeared, owing the workers months of back pay. With no managers around, it fell upon the shop floor workers to figure out how the business they had worked in for so long was actually run.

They could have opted for new managers to fill the roles of the old managers. They could have adopted the pay structures of the former company and the jobs they had all done before. But they decided to leave all of that behind and try something different. Rotating roles, equal pay and decisions made by assembly became the new norm, as the VIO.ME workers experimented with finding a new way of working together.

“When production started again in 2012, we would come every day, drink our coffee calmly, and talk about each day’s production, the money to pay for materials, and the problems that came up each day,” says Koumatsioulis, contrasting the collective nature of the factory today, with the command-and-control systems of before. His colleague, George Arvanitis, puts the difference more explicitly: “All of us, we are the boss.”

Whose voices count?

Assemblies and democratic decision making were not familiar processes for the workers of VIO.ME before the occupation began, but once they started talking, it became obvious that they had no desire to reproduce the kinds of unequal relationships that were the core of work under bosses. Even beyond the bold move of deciding to take decisions together though, they realized that they were still missing important perspectives if assemblies only included the relative few who were actually members of the newly-formed cooperative.

“After [the decision to occupy],” Koumatsioulis recounts, “we decided that we must open the factory up to society, with an assembly to decide what we were going to do next, like, what products we would sell.” Thus was born the Solidarity Assembly, a weekly gathering in which supporters and Thessaloniki residents were free to take part in shaping the direction of the factory.

Too often a company’s communication with a community is limited to occasional promotional broadcasts, or at best, hollow consultations when the decision is already a fait accompli. But the motivations for opening the gates at VIO.ME were fundamentally different, having seen how important the support of the wider community had been in helping them take back the factory. “After a lot of talk with the many who were in solidarity,” Koumatsioulis explains, “we decided that we must produce something that was going to help them.”

This decision marked a fundamental departure from the relationship between most modern companies and the local areas in which they set up shop. Rather than seeing the neighborhood as incidental to the business — one of the pitfalls of owners and shareholders making decisions from afar — the workers saw the factory as a part of the community in which they lived their lives.

With this simple grounding came one of the most radical shifts between the old and the new factory: the idea of active interdependence, rather than an incidental coexistence between the work and the lives of those in the area. People were supporting the factory, and in turn, the factory was supporting the people.

What happens when everyone is involved?

When the choice of what to make is left up to workers and communities, rather than managers and shareholders, the results improve in a range of obvious and important ways. The workers had been made ill by the chemicals used in the old production process. The local area had been polluted by the factory’s fumes. There was no investment capital to buy expensive specialist raw materials. People in the local area had seen their household incomes evaporate during the crisis.

These kinds of issues are deemed “externalities” in most companies, but what are they actually external to? In a typical company, “externalizing” important factors is a one-way street: the company gets to say everything which doesn’t produce direct profit is external to it, shedding responsibility in the process, but no one else can do the same to the company. The company is never “external” to the environment within which it is based, the community that surrounds it, or the lives of those who work there.

By involving all of these “external” perspectives — very few of which would have been particularly relevant to the planning processes carried out by VIO.ME’s former owners — a direction emerged which offered answers to a considerable shopping list of problems found in countless other communities in Greece and beyond. When left with the choice and with the various relevant questions brought to the table, the workers began manufacturing affordable and eco-friendly cleaning products, instead of toxic industrial adhesives.

Today, the factory gates no longer separate the workplace from the community, nor from the environment its emissions escape to. From what the factory makes, to what the community needs and what is best for workers’ health and the wellbeing of the planet, decisions are made together, with those who do the work and live nearby.

Through the initial act of workplace occupation, VIO.ME and countless other recuperated workplaces have begun to overcome the multigenerational failures of business owners, trade unionists, urban planners, sociologists, environmentalists and a range of policymakers, by weaving solutions to a seemingly disparate array of social, economic and ecological issues into the foundations of a single factory space.

When our opposition mirrors that which we are opposing

Corporations have made a science of isolating, externalizing, siloing and compartmentalizing themselves, under the illusion that it makes the business more manageable. In doing so, they lose perspective, zooming in on one aspect of the business or another, without ever being able to put the pieces together and see the cumulative mess they are creating.

Different teams and departments are found to be working against one another’s aims, while “the bottom line” is seen as unrelated to the company’s environmental impacts. What the company does has no perceived bearing on the world it inhabits. There is no “cause and effect,” so long as the effect falls beyond the realms of a quarterly report.

From a distance, we see the dysfunctional impacts of these false divisions, yet we often come to mirror them in the ways we organize our opposition. Unions fight for workers’ rights, green groups demand environmental protection, local community organizations push for neighbors’ concerns to be heard, but rarely do these isolated pushes align themselves, at times becoming explicitly adversarial.

We see this dynamic in clashes between trade unions representing workers in ecologically-destructive industries and environmental organizations. The unions rarely appreciate the realities that a fracking rig will have on any particular community’s environment, because they see the operation through the lens of net job gains or losses.

When that union is organizing at a national level, the issues are further isolated through the consolidation of industry workers’ common interests across the country, further minimizing the significance of any local impacts that extend beyond employment. What emerges is a single battle cry, divorced from any particular place: we need jobs. Battle cries like “we need non-flammable drinking water” are lost in the noise. They are “externalized.”

Similarly, national environmental organizations too often attribute the parts-per-million of various greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to particular industries, without understanding what those working in those industries in a particular area need. Abstract references to “green jobs” do little to calm the fears of those who see their source of livelihood threatened by people who talk about their community from an abstracted distance and lack any personal stake in the impact of their pronouncements.

However, these kinds of differences have a potential to become more aligned when we move away from large-scale centralized thematic organization (like that of governments, unions and NGOs), towards small-scale distributed community-led organization, which has a clear shared value base at its core. In closer proximity, with those most-affected involved, it is easier to find common ground.

In VIO.ME, it became clear that neither the workers nor their neighbors wanted the factory to keep producing the building industry chemicals that they had before. Without the dialogue of the Solidarity Assembly, though, it is hard to know if that common ground would have ever had the chance to surface, or if it would continue to be hidden behind the factory gates, as it had for so many years before the decision to occupy.

‘Solidarity ecosystems’

What seems to be emerging around VIO.ME and many other recuperations, are the early shoots of hundreds of connected “solidarity ecosystems.” These are interdependent social and economic networks bound together by a mix of human need, geographic closeness and a set of core values that allow them to reach beyond their immediate territories and avoid the pitfalls of tribal localism. A shared sense of solidarity connects different aspects of local life in an area with one another (work and health, for example), as well as with the local lives of countless others, further afield.

Recuperations can be hard to describe because they transcend the various institutions most of us are used to. Rather than just a change of management, recuperations represent a new form of bottom-up social organization, in which people decide together what they need, in the place they share, and take the action required to make it happen there, linking up with those further afield with similar values along the way.

A former shell of purely economic production may now address healthcare needs, alternative education provision, civic participation, food production and whatever else the people involved can create. These transformations are still in their early days, but the communities that surround these workplace recuperations are beginning to gently extract themselves from the logic and structures of capitalism and the state.

The recuperations tend to carry a sense of shared responsibility to meet community needs, but it is not addressed via one-size-fits-all welfare provision. There is certainly a level of supply and demand in the trading relations between recuperations, but it is driven by shared values and community needs, rather than lowest price and greatest profit.

The avoidance of hierarchy and promotion of collective decision making tend to transcend the different functions of a particular workplace, but no two recuperations will offer exactly the same combination of social and economic activity.

There is a clear pattern of these spaces moving beyond the remits of their former owners, towards collectively answering many of the basic questions of life for those working and living nearby. However, the specifics emerge organically in each location based on the people involved, the needs they express and the materials available.

Scaling across

The spread of workplace recuperations fits a pattern described by Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze in their 2011 book, Walk Out, Walk On, as “scaling across.” According to Wheatley and Frieze, “scaling across” is a process through which “small efforts… grew large not through replication, but by inspiring each other to keep inventing and learning.” This is about when good ideas, rather than being scaled up and rolled out by central government or multinational businesses, are passed directly from community-to-community, changing and adapting to their local circumstances in each place they take root along the way.

Scaling across is the natural extension of the bottom-up, non-hierarchical organizing patterns that are being used in recuperation after recuperation. It is the way that these (relatively) small-scale examples of social change become something more than an inspiring curiosity in one community or another. It is the process through which good ideas can become widespread practices, without an imposed model steamrolling the ever-critical local contexts they are being used in.

Wheatley and Frieze argue that “scaling across” is a way of understanding scale that is still based on individual relationships between people and groups.

A few people focus on their local challenges or issues. They experiment, learn, find solutions that work in their local context. Word travels fast in networks and people hear about their success. They may come to visit or engage in spirited communications… But these exchanges are not about learning how to replicate the process or mimic step-by-step how something was accomplished… Any attempt to replicate someone else’s success will smack up against local conditions, and these are differences that matter.

While Dmitri Koumatsioulis and his colleagues at VIO.ME have watched their own work inspire others around Europe to take over their workplaces, they initially took inspiration from workers in Buenos Aires. Some of those workers, from the Zanon factory (highlighted in Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis’ 2004 film, The Take), flew to Greece at a critical moment at the start of the occupation, to share their learning and experiences. So while VIO.ME represents a major moment in the pan-European movement for workers’ control, their early days were the result of “scaling across” more than a decade of learning from Argentina. And herein lies the real potential emerging from VIO.ME and so many other recuperations.

“Success for us is not whether this factory makes profits,” VIO.ME member Tasos Matzaris argues, “but if this example goes abroad and new factory cooperatives are being made. This is what we think success will look like.” Or as a member of the VIO.ME Solidarity Assembly echoed, “one VIO.ME is not enough… What we are hoping is that more people will follow this example and that we’ll be able to cooperate and start a network. Occupy your own company and come find us.”

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/worker-control-viome-greece/