March For Homes demonstration in London on January 31, 2015. Photo: Mark Kerrison/Demotix/Corbis

Organizing tenants in the rentier society

- November 8, 2017

City & Commons

Against the backdrop of a deepening housing crisis, new grassroots organizations are emerging to challenge landlords and governments and to organize tenants.

- Author

The financial crisis of 2008 was not just a crisis of the global economy but also a crisis of the “home ownership dream.” The bursting of the debt bubble has placed the possibility of owning a home beyond the reach of an entire generation. In the US, the UK, Ireland, Spain and many countries affected by the financial crash, renting is on the rise for the first time in a century. This is much more than a shift in housing tenures; it represents a shift in the politics of housing.

Rent increases and evictions have become key issues and even the standard of accommodation and overcrowding, in a throwback to the early decades of the twentieth century, are major challenges. The shift to renting means that more wealth is being transferred from low-income households to wealthy investors, where the former have no possibility for the formation of housing wealth through ownership and the latter are increasingly driven by financialized dynamics. The inequality at stake here is not just about wealth: renters typically have weak rights in terms of security of tenure and the regulation of rents, and as such evictions, frequent moves and abysmal quality properties are the norm.

From individual crisis to collective organizing

Against this backdrop, a new generation of grassroots organizations are emerging to challenge landlords and government and to organize tenants. Three such organizations set up in recent years are:

- Living Rent (LR), a Scottish tenant organization with branches in a number of cities. It was established in 2014 and has recently expanded into a national union of tenants.

- The Dublin Tenants Association (DTA), in which I participate. It describes itself as a space for tenants to come together to fight for their right to housing. It was established in late 2014 as a volunteer, tenant-led group. The association engages in peer-support, campaigning and advocacy.

- The London Renters Union (LRU), a soon-to-be-launched project created by a number of London housing groups with the intention of fighting “for a fair deal for renters and to build the power we need to transform our housing system.”

These organizations are developing new ways of responding to the growing conflict between tenants and landlords and between housing as a right and housing as a financialized asset. They aim to become more than radical activist groups, but rather to organize tenants en masse and to change the structural conditions and policies which condemn tenants to a life of high rents, frequent evictions and low-quality housing.

These organizations are developing new ways of responding to the growing conflict between tenants and landlords and between housing as a right and housing as a financialized asset. They aim to become more than radical activist groups, but rather to organize tenants en masse and to change the structural conditions and policies which condemn tenants to a life of high rents, frequent evictions and low-quality housing.

All the organizations mentioned above are involved in collective action in response to individual issues, in particular rent increases, evictions and poor housing standards. This involves providing information about tenants’ rights, negotiating with landlords, media campaigns targeting specific landlords and taking legal cases. For tenant organizers this is about tenants working together to fight for their rights, rather than charity.

Renting can be an isolating and individualizing experience. The only time a tenant is likely to reach out to others is during a particular moment of crisis, such as a rent increase or eviction. These moments provide the possibility to de-individualize the experience of renting, but also to politicize that experience by showing that by working together tenants can change their reality.

Yet this kind of “case work” brings its own challenges — and not just in terms of the considerable resources it requires. It risks drifting into a kind of charity-based service provision and even produce a dynamic whereby the activist becomes a kind of housing rights expert, with the tenant passively receiving their help. This is something tenant organizations are currently negotiating. The challenge is to find a way of organizing that collectivizes and politicizes individual experiences in a way that strengthens agency.

Campaigning for change

Behind these individual experiences are wider social structures that perpetuate the conditions tenants face. If these structures are not challenged the individual crises they give rise to will be reproduced indefinitely. Renters in the private sector, unlike homeowners and social-housing tenants, have extremely limited rights on all fronts, and the sector has been subject to deep deregulation. The result is that the rental sector is the “wild west” of the housing system, peppered with irrational and dysfunctional policies that even the febrile mind of the most fundamentalist neoliberal would struggle to defend.

Living Rent emerged as a national tenants’ organization in response to a consultation opened by the Scottish government in relation to security of tenure. In common with England and Wales, Scotland had one of the weakest forms of security of tenure in Europe. The inclusion of “no fault evictions” meant that tenants enjoyed effectively zero security. LR used this opportunity to engage with tenants, to shape debate and discourse around tenants’ rights and to impact on policy change.

Their main tactic was to set up street stalls and go “door-knocking” to engage tenants, inform them of the consultation and encourage them to make a submission to the consultation process. They designed a postcard addressed to the relevant government department, which tenants could fill out. At the end of the process, Living Rent delivered sacks full of the postcard submissions to the consultation process. The focus of LR’s campaign was on security of tenure including ending “no fault evictions” and securing long-term security for tenants. However, rent levels, which were not originally included within the consultation process, were also raised by LR, and their campaign included a demand for rent controls.

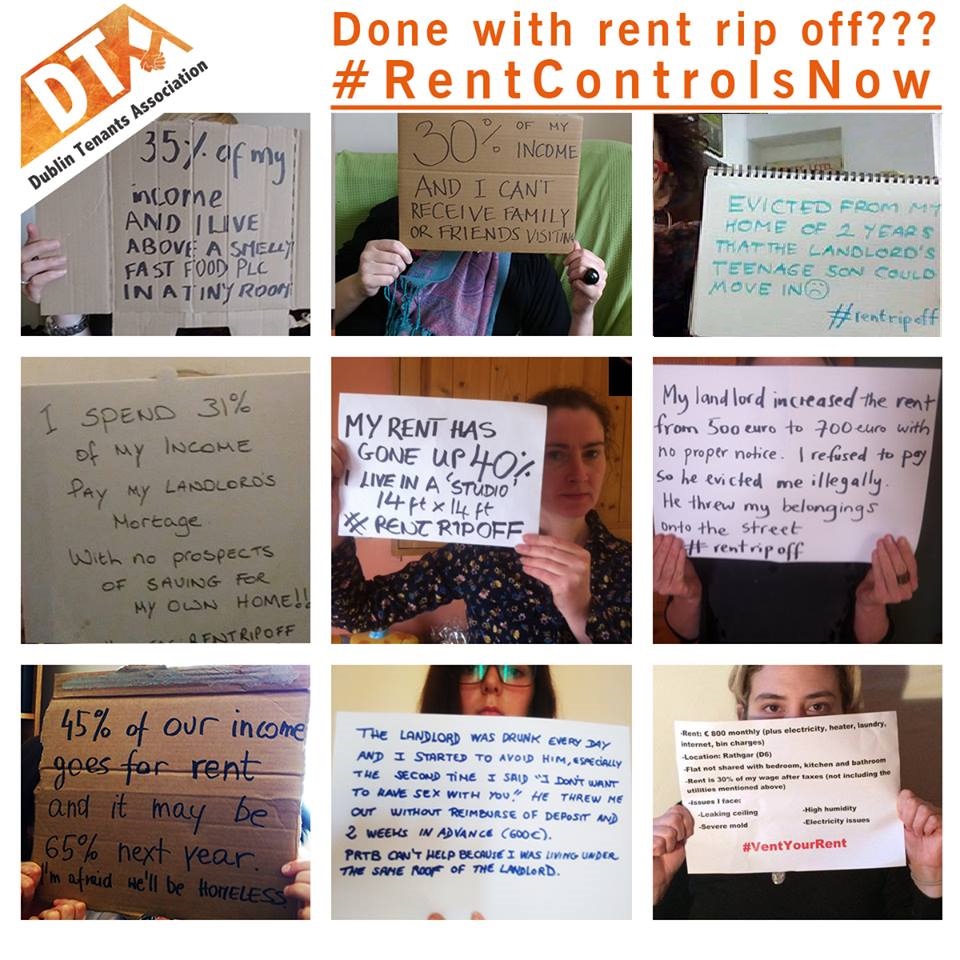

The Dublin Tenants Association, meanwhile, also conducted a campaign for rent controls and security of tenure in the context of a government consultation process in 2016. Tenants were asked to take photos of themselves holding a placard stating the impact of high rents on their lives and share them on social media. This was the first time, at least in recent decades, that tenants have featured as an organized and public voice in debates about housing.

The campaigns conducted by LR and the DTA met with a surprising level of success. Particularly in the case of LR, policy reforms were introduced that far exceeded what might have been anticipated. Indefinite security of tenure was introduced and regulation of rent increases, which was initially not even included in the policy agenda, was also introduced. A form of rent control has also been introduced in Ireland, as well as moderate reforms to security of tenure, although this was a result of a concerted campaign by a variety of civil society actors, in particular housing charities, and cannot solely be attributed to the DTA.

Successes and challenges

A number of factors help explain the effectiveness of these campaigns. Firstly, both DTA and LR achieved a very effective and informed engagement with policy. This has also been a strength of Generation Rent, one of the constituent groups of the London Renters Union. In critiquing current policy and developing alternatives, examples from other European countries were also important. For example, both DTA and LR were able to point to data from countries such as Denmark and Austria to show that tight regulation of rent increases is compatible with adequate supply of rental accommodation.

A second theme is effective engagement with the media. This is enormously facilitated by a firm understanding of policy detail, which makes possible credible arguments and proposals but also allows activists to combat anti-tenant perspectives. Media work was further facilitated by the fact that none of these countries have heretofore had organizations representing or advocating for tenants as a specific social group (at least not in recent decades). This created a vacuum that tenant organizations could fill.

Tenant organizations have furthermore developed a language to speak from a tenants’ perspective, reflecting the experiences of tenants but also articulating “tenants” as specific social actors and as a collective. Creating this sense of collectivity is a specific goal of tenant organizations to counter the individualizing nature of renting. The DTA, for example, set out from the beginning to develop a language through which to speak to and for tenants, based closely on their experiences rather than relying on a traditional left-wing discourse to produce a readymade critique of the rental sector. This is not just a case of “representing tenants” and communicating with them, but a case of speaking as tenants.

There are, however, a number of challenges in campaigning for renters’ rights. There is a danger of falling into a representational politics in which tenants become almost a “consumer group,” whose interests need to be factored into the policy process. This depoliticizes the fundamental antagonism between renters and landlords, and between a home as a right and as a speculative asset. It also potentially divides tenants in the private rental sector from those in social housing.

Furthermore, there are class divisions and other forms of stratification operating within the rental sector. This is typically ignored by media reports, which tend to focus on a “generation rent” consisting exclusively of “young professionals.” Minorities, migrants and female-headed households are very significantly over-represented within the rental sector, but may be underrepresented in tenant organizations. The London Renters Union has paid particular attention to this issue and organized extensive engagement designed to create an inclusive organization that is led by the different social groups that make up renters.

Unionizing and organizing tenants

Of the three organizations discussed here, two have established themselves as tenants unions, meaning they have a fee-paying membership structure. Tenants formally join the union, pay monthly due, are able to participate in decision-making, and are eligible for support such as legal advice.

The power of the union model is that it can combine and strengthen both casework and campaigning, the two principal forms of action which tenant organizations are already engaged in, and as such achieve the kind of mass-scale required to bring about structural change. In particular, a fee-paying membership creates independent revenue, which allows for hiring paid staff. LR and the LRU both view paid staff as a prerequisite for organizing effectively on a mass scale, and have either already hired staff or are in the process of doing so.

The DTA is more agnostic about the benefits of a somewhat professionalized structure. Indeed, all of the organizations are concerned about the political questions at stake in creating a well-structured union with paid staff, and this will no doubt be a challenge to be confronted — and hopefully overcome — as the organizations develop.

The DTA, LR and LRU are certainly not the only grassroots tenant organizations springing up across Europe. Acorn, the grassroots “community union,” is organizing around tenants’ rights in a number of English cities, and renters’ unions have recently been launched in both Barcelona and Madrid. The proliferation of these groups tells us something important about how the politics of housing is changing today. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the focus among many researchers and activists was on the issue of housing debt and the associated forms of social conflict and activism. Mortgage arrears and repossession have been important political issues in Ireland and the United States, but most significantly for the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) in Spain.

However, new banking regulation and more stringent credit standards coupled with declining wages and job security make accessing mortgages increasingly difficult. Today, the principal drivers of housing inequality are not excessive debt levels but exclusion from access to credit and homeownership. As households find themselves increasingly relegated to the rental sector for life, and with social housing continuing its decline, the types of issues which dominated “the housing question” in the early twentieth century have returned to prominence: rent increases, evictions, overcrowding rack-renting, and so on.

Political and social conditions today are, however, markedly different. The tenant organizations of the past typically organized in locally concentrated, neighborhood-based working-class communities characterized by relatively high levels of homogeneity and well-formed social networks. Much like the situation faced in precarious workplaces, today’s tenant organizers confront a highly fragmented and individualized rental sector. The challenge, then, is not just to mobilize tenants but to create a shared sense of being a tenant in the first place, as well as the social relations, forms of discourse and shared culture of organizing and political practice required to sustain any successful movement.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/organizing-tenants-rentier-society/