Photo: Carlos Wagner

Chile’s feminists inspire a new era of social struggle

- January 26, 2019

Gender & Governmentality

Feminism has a long history in Chile, but 2018 gave rise to a movement that was far more powerful than anyone could have expected.

- Author

It is May 2018 and as winter descends on Santiago, Chile, a new wave of feminist activity is exploding into life. Anti-patriarchal graffiti covers the city walls and streets are littered with the evidence of recent marches. Tension is rising in the universities and social media are flooded with posts ranging from cautious inquiries to joyous declarations: “Is the downtown campus of PUC occupied?” “Was UCEN taken over?” “Instituto Arcos on feminist strike!”

Almost every day, a new selection of feminist banners can be spotted hanging from the fences of Santiago’s most prominent institutions. One by one, the universities and high schools are falling to feminist occupations, but somehow it still only feels like the beginning. Feminism is on the rise, and while there may be messages of sorority in abundance, they are sharpened by an intense anger directed squarely at those who have wielded patriarchal power against the women of this country.

To an outsider, the feminist movement in Chile might come across as a strong, unified mass movement, with a large number of diverse organizations joining the annual mobilizations. But what at first glance might be taken as a well-developed expression of feminist power was in reality much more fragmented. The movement was in chaotic transition, disrupting and challenging the left as a whole, but without a clear vision of what new practices would replace the old.

A new wave of Chilean feminism

The frustration and outrage felt by women, trans people, and queers had clearly been intensifying for years, but the tension had yet to find release in a mass, popular movement. Everyone could feel something coming, but no one was sure which combination of events would finally crack the dam. The flood would come in April 2018, with a massive wave of university and high school occupations, all carried out in the name of feminism.

The Chilean student movement has a long, rich history, most recently marked by periods of struggle in 2006 and from 2011 to 2013 and can seem quite exotic to foreign audiences, thanks to iconic photos of occupied schools and massive mobilizations. However, there is a danger in romanticizing these superficial images of struggle. The risk is that without historical grounding or contextual analysis, this current spectacle of youthful, feminist rebellion will obscure the far more intriguing political developments taking place away from the cameras.

The students may have been the first to throw open the door, but many more may soon walk through it. Feminist activity has re-awoken in the working class neighborhoods of Santiago and is stirring in the rapidly expanding migrant community. Workers’ movements are integrating an analysis of reproductive labor and even some traditionally masculine unions are considering going on strike for feminist demands.

This new wave of Chilean feminism will be explored in a series of three articles with a specific focus on the multisectoral and transversal tendencies within the movement which arguably hold the potential to unite Chile’s diverse social movements into a force capable of presenting a real challenge to the triad of capitalism, patriarchy and the state. This first part in the series looks at the conditions that gave rise to this fresh cycle of struggle as well as the emergence of La Coordinadora 8 de Marzo, the coalition currently serving as the primary vehicle for this political approach.

Feminists against femicide

Currently, the wave of strikes is already subsiding and the movement is charting a new course. However, Chilean feminists are still struggling to analyze the moment in which they have found themselves. It is not enough to simply react; we must understand where we have been in order to determine where we will go from here. This process of reflection will be ongoing, but several contributing factors can be clearly identified: the surge in global feminist visibility, the parallel ascensions of other social movements and the pressure exerted on all Chileans and Indigenous peoples through the continued application of the neoliberal policies instituted since the return of democracy.

Chileans are very sensitive to international political trends. The #metoo movement in the US and its equivalent in Spain, #yotecreo (“I believe you”), aligned neatly with Chile’s history of funas — a tactic where people congregate around the homes of public figures or known abusers in order to denounce and shame them for human rights violations or patriarchal violence. This tool is used when people believe there is no other recourse for justice, which is often the case with individuals who escaped criminal prosecution for their roles during the military dictatorship. Unfortunately, this also applies to abusers who are often free to live their lives and perpetuate violent behavior without experiencing any consequences.

In the modern era, funas have gone digital and young women bravely post photos of their bruised faces on social media accompanied by explicit accounts of their abuse. These women are naming names and sharing screenshots, taking advantage of modern means of communication to highlight their daily struggles.

#NiUnaMenos (“not one [woman] more”) is a slogan against femicide which originated in Argentina and resonates strongly with Chilean feminists, giving life to such organizations as the Coordinadora #NiUnaMenos (NUM Coordinator), which successfully instigated massive mobilizations throughout 2016 and into 2017. Femicide is a dominant theme in Latin America, so much so that it feels like every week brings a fresh headline about a woman murdered out of jealousy or as a punishment for stepping beyond traditional gender expectations.

June 25, 2018, for example, marked the second anniversary of the death of Nicole Saavedra, a young lesbian from a rural community who was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered. Family members and activists have charged that the investigation of Nicole’s death was neglected due to the lack of importance placed on the lives of women, and those of lesbians in particular. This is a recurring theme for Chilean feminists, who are met with resistance from both the government and media when they insist on the existence of femicide as a unique category that cannot be understood or combated in the same way as other homicides.

For many who organize to combat the persistent themes of domestic abuse, sexual violence, and femicide, the fight against apathy and resignation is a struggle in and of itself. In Chile, remembering is not only about personal reflection. Rather, it is political process that prevents the loss of collective knowledge and preserves the memory of martyrs. Contemporary feminists use the politicization of memory in the same way as the older generation who lived under the dictatorship: by honoring victims of femicide through art and political struggle.

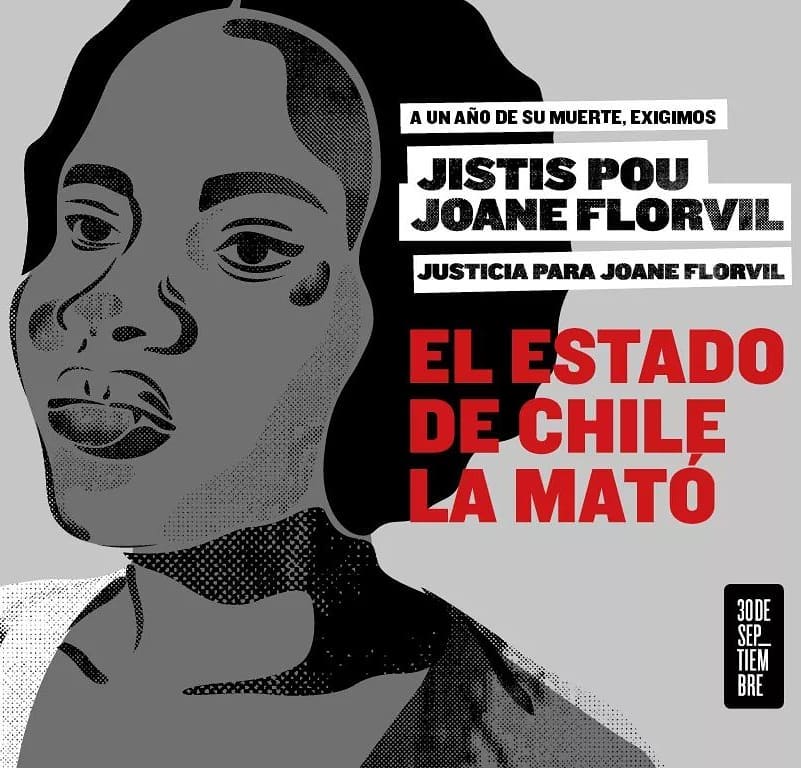

In late 2017, the struggle against femicide and gendered violence converged with the immigrant rights’ movement with the death of Joane Florvil, a young Haitian woman accused of abandoning her infant daughter. She was subsequently arrested and held in detention until her death 30 days later, allegedly due to injuries incurred during her arrest. As a recent migrant who didn’t speak Spanish, Joane was placed in a position of hyper-vulnerability, unable to explain her actions to the police or to defend herself against their accusations. Her death has since become emblematic of growing xenophobia, a problem which is further exacerbated by anti-black racism and misogyny.

As migrants continue to surge into the country in unprecedented numbers, the left has struggled to adapt to this new political landscape. Chilean feminists have been some of first to extend a hand to the Haitian community, building bonds through activism and popular education projects. With the passage of a new decree that singles out Haitians for a more restrictive immigration process, feminism has the potential to become the lens through which this crisis is understood and confronted.

Multisectoral movements

The themes of income disparity, reproductive labor, and precarity have been taken up most notably by the Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras No Más AFP (National No More AFP Workers’ Coordinator, or No+AFP), the coalition organized to reform or replace the corrupt pension system. This movement has been propelled forward by female trade unionists — among others — and hasn’t hesitated to highlight how women are uniquely disadvantaged under the current capitalist system due to gender-based income disparity and the uncompensated nature of work in the home. The women of No+AFP are often active participants in neighborhood assemblies and political organizations and represent a traditional image of Chilean working class activism.

Tension emerges when the feminism of the labor movement and poblaciones — shantytowns or working-class communities — intersects with the feminism of the student movement, which has largely, but not exclusively, been developed in the context of the most politicized high schools and universities. Certainly there is a vast gulf of experience between poor, rural Chileans and those who are able to attend the best universities in the capital city of Santiago. That said, it is the project of every social movement to identify the common threads capable of binding these groups together across and through their diverse experiences.

The neoliberal policies instituted under the dictatorship and expanded on by subsequent right-wing governments have impacted the lives of all Chileans and indigenous people. Therefore, movements against state violence and privatization in the areas of education, social security, healthcare and labor have everything to gain from recognizing and acting on their complementary objectives.

This multisectoral approach is exemplified by the national organization Movimiento Salud para Todas y Todos (Healthcare for All Movement, or MSpT), which unites healthcare workers, medical students and patients to demand healthcare as a public right. They pursue this goal through many diverse campaigns, including support for Mapuche hunger strikers, improvement of patient conditions, public health education workshops and the decriminalization of abortion. In the language of the Chilean left, sectors are defined areas of struggle, such as labor, territorial — land and community — and student.

Multisectoralism means having a cross-sectional analysis of these social movements and developing relationships of solidarity across these sectors, resulting in multisectoral support for specific demands.

The multisectoral movements of today reflect the experiments and advances of the past, as evidenced by the Chilean student movement which has proven itself to be remarkably flexible, capable of incubating new ideas and putting them into practice. One such idea was “sexual dissidence,” a radical answer to the neoliberal politics of inclusion and diversity. Popularized by such groups as Colectivo Universitario de Disidencia Sexual (Sexual Dissidence University Collective, or CUDS), sexual dissidence denotes “constant resistance to the prevailing sexual system, to its economic hegemony and its postcolonial logic” and rejects the idea of subversive identities — gay, lesbian, queer, trans, drag, etc. — in favor of subversive analysis and action. The result is an inclusive, combative politics that cannot be easily co-opted or institutionalized, no matter how many individuals are peeled away by token reforms.

Since the theorization and practice of sexual dissidence developed in conjunction with the growth of student feminist activity, there is a significant tendency that has proved resistant to trans-exclusive radical feminism. This influence is most visible in feminist assemblies and demonstrations in Santiago where trans and nonbinary feminists show up in far greater numbers than can be seen in the US and even hold leadership positions in their organizations.

Contemporary Chilean feminism is refreshingly experimental and resilient, grounded in historical leftist analysis, but open to integrating new theories and tactics as they emerge on the global level. By maintaining a class struggle orientation and infusing their analysis with lessons learned from Black and Indigenous feminisms, this generation of feminists has advanced the struggle much farther than was previously considered possible. However, there are a number of forces that stand in ideological opposition and seek to sabotage the movement at every opportunity.

Co-option, Fascism, and Threats From Within

The first threat comes from the current Piñera administration which immediately rolled out token healthcare and labor reforms with the intention of giving a “pro-woman” face to the same old policies that have caused so much harm to Chile’s social infrastructure. These reforms are the carrot dangled in front of political moderates, while the stick is represented by harsh new policies which seek to further criminalize both migrants and Mapuche — the Indigenous people who inhabit central and southern Chile.

Piñera’s neoliberal strategy can be understood as the “gentler” approach compared with the borderline fascist positions taken by contemporary far-right politicians such as José Antonio Kast, whose 2017 presidential campaign promised a return to “law and order” and was welcomed by traditional conservatives. His hard-line positions on immigration and social issues such as abortion have made him an inspirational figure to fascist groups organizing on the grassroots level. The ascent of nationalist and ethno-supremacist movements globally has given Chilean fascists a feeling of increased legitimacy, and the threat of organized violence against Black migrants and feminists is moving from empty posturing to real violence on the streets.

Unfortunately, the final — and possibly most potent — threat comes from within the movement itself, which has been plagued by ideological splits and power struggles. After instigating mobilizations throughout 2016, the Coordinadora NiUnaMenos (NUM) effectively tore itself apart. The first split came as a result of the actions taken by one of the member organizations, Pan y Rosas (Bread and Roses), which sought to use its superior numbers to compel the coalition into defending controversial positions. This exposed a significant ideological split between anti-organizational feminists who advocated for separatism and those feminists who maintained membership in traditional gender-mixed leftist groups.

As internal crises continued to batter the coalition, the atmosphere grew toxic and political debate devolved into bullying and personal attacks. Before this series of events had finished playing out, the remaining pro-organizational feminists collectively determined that the coalition was no longer a safe or productive vehicle for their politics and chose to make their exit.

For some, the disintegration of NUM must have been a cruel disappointment, especially after experiencing such a vibrant resurgence of feminist activity. However, the feminists who had discovered political affinity while navigating the coalition’s myriad conflicts were far from despondent. On the contrary, the adversity they experienced forced them to hone their political analysis and articulate fresh alternatives to the positions and practices they opposed.

In this way, the metaphorical blood shed in this difficult period came to fertilize the soil from which the next stage of the movement would grow. At the close of 2017 some feminists continued to turn to groups of friends or separatist spaces for politics, while others began to grapple with the project of defining feminism as something transversal, multisectoral and far more ambitious than what had come before.

Naming the Moment

Thus we arrive in January 2018, with a mosaic of social movements, leftist parties, cultural collectives, neighborhood assemblies and politicized individuals repositioning themselves to confront the new political landscape unfolding as the Piñera administration prepares to take power. It is in this context that the Coordinadora 8 de Marzo (March 8th Coordinator, or C8M) met to discuss the coyuntura — the combination of factors that characterize the political moment — of Chilean feminism.

C8M is a coalition with a deceptively simple mission: to bring together a variety of social organizations, labor unions and individual feminists to plan the annual march associated with its name. Every year, veteran participants and newcomers must coalesce around a common analysis of the state of feminist struggle and identify a theme capable of uniting a heterogeneous and conflictual movement.

The feminists of C8M, many of whom were veterans of the conflicts of the #NiUnaMenos era, knew that isolationist separatism was a dead end for their political objectives. To build the movement they knew was necessary, they needed to find the common thread that passed through the lives of all working-class women and gender dissidents: something to bring people together instead of tearing them apart. Towards this end, they adopted a transversal feminist approach.

Transversal politics is an organizational method designed to generate collective identity in non-hierarchical coalitions across the diverse positionalities of their members. In fact, these very differences are considered an asset, since it is only through analyzing a problem from multiple perspectives can “the truth” be ascertained. This method seeks to avoid the excessive universalism of the left which flattens differences, often in an ethnocentric manner, as well as the excessive relativism of contemporary identity politics, which are often essentialist and substitute individual identity for collective identity. In Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, Patricia Hill Collins writes that in order to build bonds of solidarity across our differences, “Empathy, not sympathy becomes the basis of coalition.”

C8M would come to define two commonalities through which to channel this politicized empathy: the experience of individual and structural violence and the condition of working for others. The latter was interpreted in a broad way, acknowledging that women’s labor takes many forms, both salaried and informal, and must be made visible in all places it occurs. This analysis opened the door for feminist struggle on all fronts, permeating all social movements positioned against capitalist exploitation and state oppression. It was possible, they posited, that feminism itself could become the commonality to unite and reinvigorate the left as a whole.

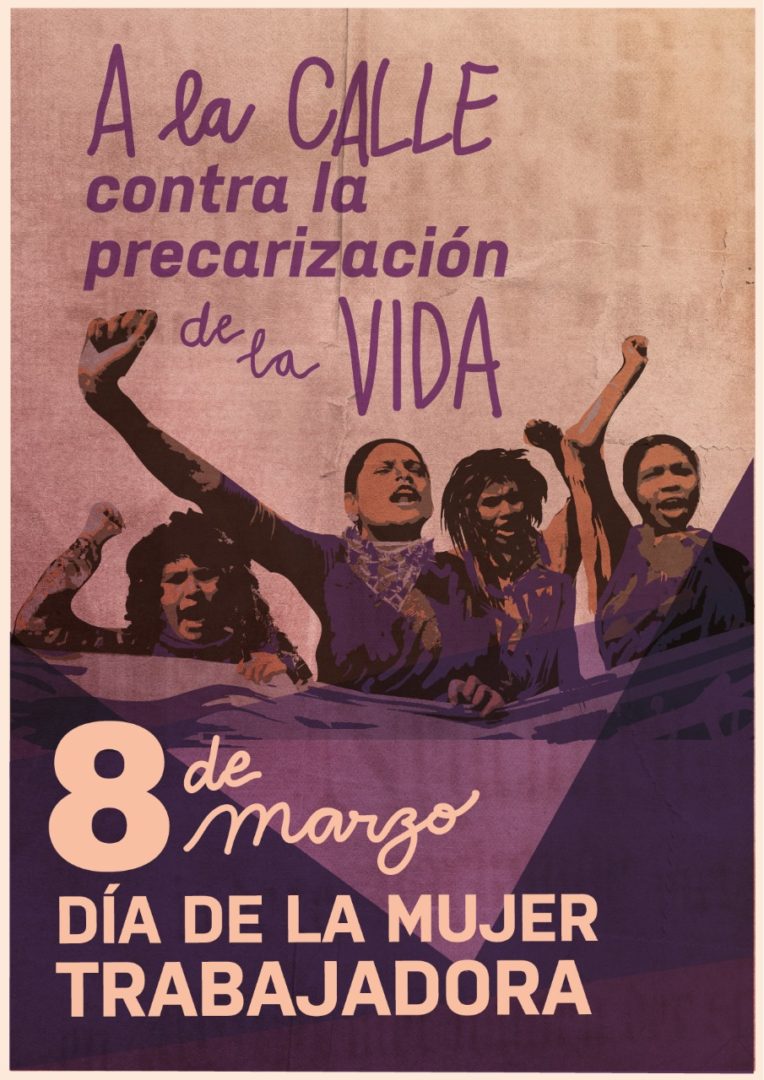

What slogan could possibly speak to this common condition of labor exploitation and violence in all its myriad expressions? This year, C8M decided, feminists would mobilize “Against the Precaritization of Life.” This theme spoke to the effects of 30 years of neoliberal policies instituted in Chile after the return to democracy. While not always explicit in their targeting of women, the result of these policies was the further immiseration of a group already placed at a historical disadvantage.

Whether a Mapuche on her ancestral territory, a student in the classroom, a worker on the job, a mother or care-taker maintaining her home and family or an immigrant building a new life, all women have felt the sting of intimate or structural violence and the systemic stripping of their autonomy and resources by the state. The 2018 march would, by necessity, bring together the territorial organizations of the poblaciones, the zonal formations of NO+AFP, the female-dominated trade unions, the numerous student feminist organizations, immigrant and human rights organizations and many, many more, essentially representing a broad picture of Chilean social movements, all united through feminism.

This convergence of struggles was evident on March 8, 2018, when a seemingly never-ending stream of feminists overflowed the streets. The general feeling was that something significant had shifted, that forces were coming into alignment. Months later, members of C8M would reflect that they knew discontent was rising in the universities as early as their first meeting in January. That said, few could have predicted the massive wave of feminist strikes and occupations that would sweep away schools and universities throughout the country just a few short weeks later or the reinvigoration of the movement for abortion rights that would soon follow.

You can read the second part of this triptych on Chilean feminism, “Chile’s feminist movement is here to stay”, here.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/chile-new-feminist-movement/