View of the Porto Marghera industrial area. Photo: Clara_C / Shutterstock

Exiting the false “jobs versus environment” dilemma

- November 16, 2020

Work & Workers

The workerist environmentalism of Italy’s Porto Marghera group connects the workplace and the community in the struggle against capitalist “noxiousness.”

- Author

Amidst the renewed rise of obscene inequalities, a wave of protests is sweeping through Italy, from south to north. On the one hand, the pandemic has engendered an upsurge in workplace disputes to defend health and in mobilizations to protect the income of workers affected by COVID-19-related restrictions. On the other hand, however, we have also witnessed successful interventions coordinated by the right and infused with a bewildering array of conspiracy theories in response to such measures.

Different from the slogan that emerged at a mass demonstration in Naples on October 23, 2020 — “If you lock us down, pay up!” — the right-wing discourse does not ask for more collective and egalitarian forms of prevention. It demands instead that “the economy” be allowed to run smoothly. Nonetheless, the right-wing side of dissent appears to attract a significant working-class presence, as many workers — rightly concerned about the impact of months-long lockdowns on their livelihoods — find an answer in negating the gravity of the pandemic and of the environmental crisis more generally.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Marxist commentators have underlined how the health crisis cannot be separated from the economic system that shapes our lives. This does not just concern inadequate healthcare systems: the very spillover of the novel coronavirus from non-human animals to humans was caused by the capitalist imperative to appropriate natural “resources” to safeguard the profit margins that drive the economy forward.

In a way, the pandemic is a global manifestation of the “jobs versus environment dilemma” and the related “job blackmail,” a situation in which workers are faced with a choice between defending their health and environment or keeping their jobs. There is no easy way out of this dilemma. However, the reflections developed some 50 years ago by a workerist collective mainly composed of workers employed in the highly toxic industrial complex of Porto Marghera in Venice, Italy could still provide a source of inspiration.

Workerist environmentalism in Italy

Workerism, or operaismo, is a New Left current that emerged around the struggles of Italian factory workers in the 1960s, mainly through the reviews Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia. This theoretical tendency informed the rise of several radical organizations in the late 1960s and 1970s, such as Potere Operaio, Lotta Femminista, and Autonomia Operaia.

Workerism is not famed to have much to say about environmental and health issues, yet this impression overlooks the theory and praxis on nocività (literally “noxiousness” or “harmfulness”) by the Porto Marghera workerist group. The group was active under different names between the early 1960s and 1980 in the large industrial cluster located in the Venice council area. It originated through the encounter between militant workers, students and intellectuals disaffected with the line of the Italian Communist Party and its associated union Italian General Confederation of Labor.

Their elaborations are little known — a result of the fact that the protagonists of this experience were factory workers and technicians rather than “full-time intellectuals.” Their reflections can be found scattered across a myriad of factory flyers and newspaper articles published on Potere Operaio’s homonymous review and later on the group’s local reviews Lavoro Zero and Controlavoro.

The Italian word nocività or noxiousness refers to the property of causing damage. Through its use by the labor movement, it came to encompass damage against both human and non-human life. It can then be translated neither as (human) “health damage” nor as (non-human) “environmental degradation.” The Porto Marghera group argued that noxiousness is inherent to capitalist work. They began to address such issues during the late 1960s, a time when the workerists had a determining influence in Porto Marghera’s class struggles, due to the extreme toxicity and hazards they faced in the local factories, particularly Montedison’s gigantic Petrolchimico. This case of working-class environmentalism is remarkably prescient. From as early as 1968, it involved workers employed by polluting industries denouncing environmental degradation — beyond workers’ health — caused by the very companies they worked for.

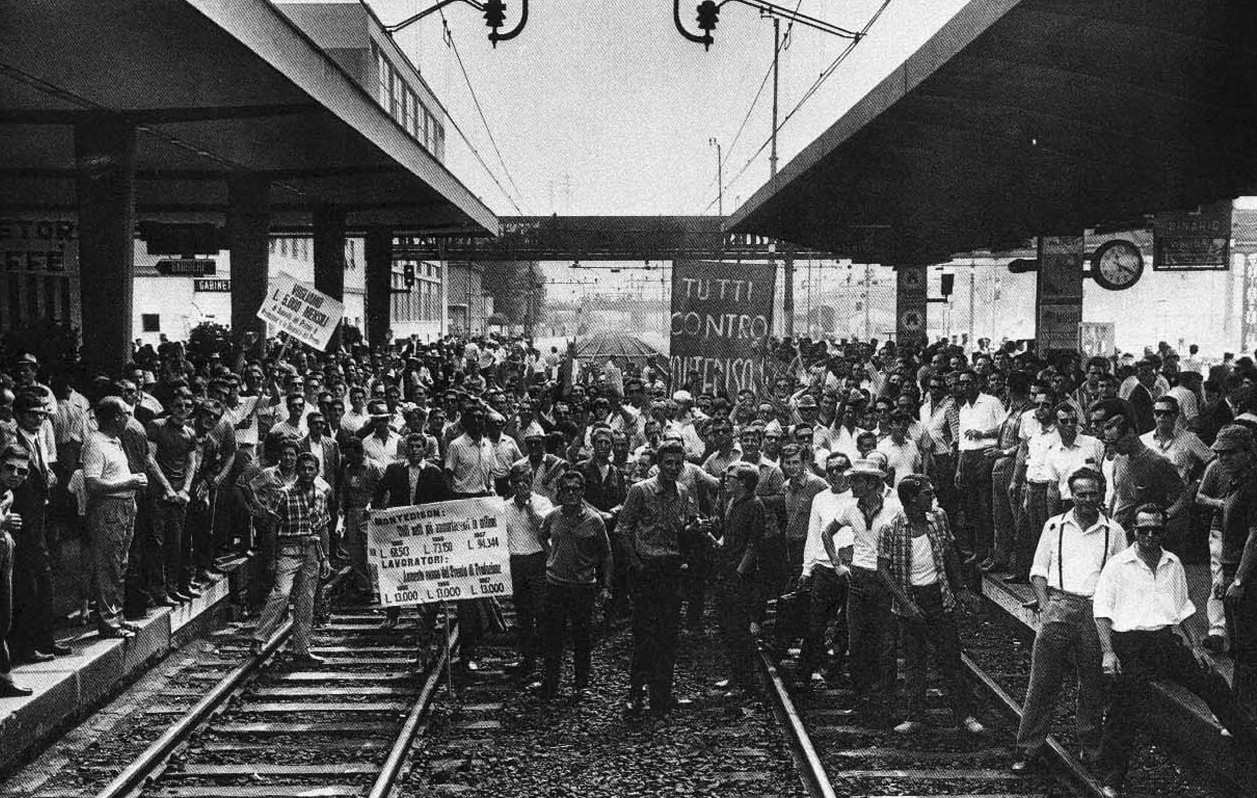

Workers’ militancy at Petrolchimico exploded in the summer of 1968 which culminated in the occupation of the Venice-Mestre train station on 1 August. Courtesy of Luciano Mazzolin’s Porto Marghera Archivio Ambiente Venezia

The group’s theorizing on noxiousness was spearheaded by a technician at Petrolchimico named Augusto Finzi. Born in 1941 to a Jewish family, Finzi spent part of his early childhood in a refugee camp in Switzerland to escape the Holocaust, in which the German chemical industry — the most advanced of the time — had played a key and dreadful role. After receiving a high school diploma in chemistry in 1960, he immediately began working in a Petrolchimico VCM-PVC unit. In 2004, he died of cancer. Premature death was indeed widespread among his co-workers at Petrolchimico.

The Porto Marghera group linked noxiousness to the workerist “strategy of refusal.” In this perspective, capitalist work is the production of value and thus the reproduction of a society of exploitation. Therefore, class struggle is not an affirmation of work as a positive value, but its negation. As Mario Tronti put it: “A working-class struggle against work, struggle of the worker against himself [sic] as worker, labor-power’s refusal to become labor.”

The combination of the refusal of work with the dire health and safety conditions they experienced led the Porto Marghera group to the core idea that capitalist work is inherently noxious:

Workers do not enter factories to make inquiries, but because they are forced to do so. Work is not a lifestyle, it is the obligation to sell oneself to make a living. It is struggling against work, against the coerced sale of themselves, that workers clash against all norms of society. It is struggling to work less, not to die poisoned by work, that they also struggle against noxiousness. Because it is noxious to wake up every morning to go to work, it is noxious to accept productive paces and conditions, it is noxious to take the shift system, it is noxious to go home with a wage that forces you back into the factory the day after. (Assemblea Autonoma factory flyer, February 26, 1973)

An early version of the group’s reflections was partially systematized in the paper “Against Noxiousness.” Its core assumptions are still very useful today:

It is necessary to immediately distinguish between one form of noxiousness — i.e. that traditionally understood — linked to the work environment (toxic substances, smokes, powders, noise, etc.), from the one linked more generally to the capitalist organization of work. No doubt, ultimately, the second type of noxiousness has a deeper impact on the worker’s psychophysical balance. It makes him [sic] an alienated entity, a piece of the productivist machine completely detached from the end of his work and subject to the continuous usury that brings upon him an inhuman use of his labor-power as it is the capitalist one, driven exclusively by the profits of the ruling class. (Comitato Politico, February 28, 1971)

According to this perspective, struggles for health targeting traditional noxiousness only —like the one proposed by their local unions to reform the work environment — are insufficient because they would only be harnessed towards the requirements of capitalist restructuring, while leaving the crux of the matter — i.e. the priority of value production over life reproduction — untouched: “In the new factory, coupled with a modest reduction in toxicities and thus in occupational diseases traditionally understood, there will be a strong increase in mental health disorders.” Instead, the group commended the tactic of worktime reduction with no wage cuts to transform the fight for survival in the factory into a struggle for liberation from capitalist work.

Following in the footsteps of Italian workerist pioneer Raniero Panzieri, a critique of capitalist technology was already in the Porto Marghera group’s equation (see also the “Refusal of Work Manifesto”). Safer machinery was necessary, “but maybe a new race of engineers is required to build machines that would not destroy health and enormously increase profits.”

The group criticized the union line of demanding more growth — rather than shorter hours — to protect employment levels, as such investments would result in automation and layoffs, as “[t]he bosses are still using automation in an anti-worker function. The introduction of new machines and computers does not lead to a decrease in working hours but to an increase in their profits.” Under such conditions, automation should not be accelerated. The group thus adopted an antagonistic-transformative approach to capitalist technology that eschewed both an instrumentalist view according to which capitalist machines are neutral means that can be unproblematically repurposed for anti-capitalist ends and the wholesale rejection of technology as such.

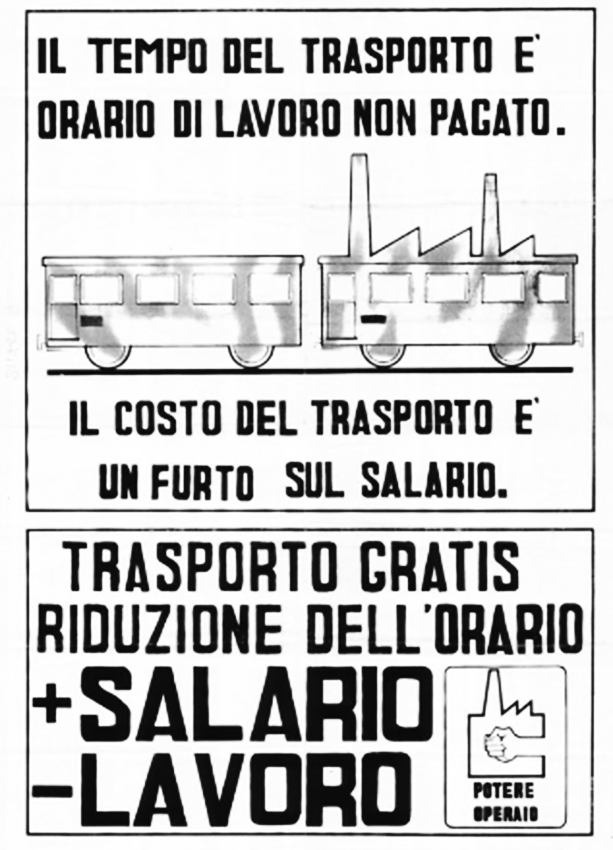

Flyer from 1970 demanding that the time for commuting to work be counted as worktime, as part of the campaign for “More money, less work.” Courtesy of Luciano Mazzolin’s Porto Marghera Archivio Ambiente Venezia

Over the course of the 1970s, the Porto Marghera group complemented its quantitative focus on “more money, less work” with a qualitative reflection on “what, how and how much to produce.” The latter was linked to the concept of “proletarian self-valorization,” or working-class empowerment through the production, re-appropriation and sharing of use values for the satisfaction of collective needs. The group then added self-valorization to the fight against noxiousness, proposing the construction of a counter-power connecting workplace and community struggles geared towards a transition to a system based on collective needs, understood as involving a mutually sustaining relationship between human health and the environment.

In this framework, it was deemed “more valid to change the content of production rather than [merely] taking over the productive apparatus.” . But what do these ideas tell us about the current crisis?

“Noxiousness” during a pandemic

In capitalism, the ways in which noxiousness appears are shaped by the law of value and its competitive pressures on the labor process. Pandemics happened in pre-capitalist societies too. But in a non-capitalist society, work mainly produces use values. This can happen under different modes of production, such as under the coercion of a feudal overlord who appropriates a share of the product but also — in principle — on the basis of democratic planning on what and how much to produce and at what conditions.

Under a capitalist mode of production, instead, workers must ensure their employers’ profitability. In the current pandemic, the noxiousness of millions of infections and deaths was brought about and molded by the competitive pressures that drive environmental destruction and tie workers’ survival to it.

In 1973, the Labor Inspection required all Porto Marghera employees to work with a gas mask within reach due to the severity of toxic hazards. The order provoked widespread outrage as it implied that highly unsafe working conditions need not be eliminated. Courtesy of Luciano Mazzolin’s Porto Marghera Archivio Ambiente Venezia

In Italy, the government’s response to the pandemic included a blockage on layoffs for workers with open-ended contracts, the provision of exceptional — albeit meager — income-support allowances for self-employed workers as well and the expansion of the capacity of public hospitals. Yet, given that the state depends on capital accumulation for its revenues, such mitigations are similarly subordinated to the preservation of the mode of production. Within this logic, the costs of the partial health and subsistence protections recently conceded to the workers in several countries will eventually be offloaded on the working class through rounds of austerity and restructuring proportional to the massive magnitude of the crisis.

As the subsistence of the working class is conditional on capitalist work, workers need jobs and thus endless economic growth to survive, no matter the health and environmental consequences. This kind of “job blackmail” does not apply solely to large-scale, highly toxic industrial complexes. It actually holds sway across capitalist society and is intrinsic to it. If reproductive needs — like the need for a healthy ecology — are the material basis of working-class environmentalism, the link between workers’ reproduction and capitalist work is the material basis of working-class negationism and must be broken.

Anti-capitalist interventions in the current cycle of struggles should build on demands for the long-term satisfaction of workers’ reproductive needs to make working-class environmentalism a winning alternative to working-class negationism. In the ongoing protests over the Italian government’s COVID-19-related measures, the slogan “Income and health for everyone” points in the direction of working-class environmentalism, while “Let us free to work” tends towards the pole of working-class negationism to the extent that it also refers to jobs where the risk of COVID-19 diffusion is high.

So, if workers are dependent on the very noxiousness of capitalist work to live, how can they struggle against it? The Porto Marghera group’s initial proposal, in line with the workerist strategy of the time, was an egalitarian call for “more money, less work” to break the link between the wage and productivity, throwing capitalism – or so they hoped – into a terminal crisis. This resulted in the demand for what was called a “guaranteed wage for all,” similar to today’s radical proposals for a universal income. The group later added to this quantitative platform a qualitative one that, through an antagonist-transformational approach to capitalist technology, posited the construction of a counter-power able to change “what, how, and how much to produce.”

Applied today, this strategy to exit the “jobs versus environment” dilemma could look like a platform centered on shorter hours, radical wealth redistribution and a just transitions to sustainable and non-commodified production as transitional steps towards the transcendence of capitalism, articulated with the anti-racist, feminist and anti-imperialist aspects of the struggle.

One example of an attempt to do this is the Climate Camp hosted in Porto Marghera by the Rivolta Social Center, an autonomous space that continues the thread of working-class environmentalism initiated by the Porto Marghera group and carried over through the 1980s and 1990s by rank-and-file unions and leftist environmental associations.

With the active participation of radical unions, the Climate Camp endorsed an environmentalist version of universal income — partially in money and partially in de-monetized goods and services — that differs significantly from the accelerationist one, in that such income would be funded through just degrowth and radical wealth redistribution, rather than through further capitalist automation. At the same time, the “what” and the “how” of production must change too.

The organizations that participated in the Climate Camp are now mobilizing to demand that workers’ subsistence come not from working at any cost — including the further rapid spread of viral contagion — but from making the rich pay for COVID-19 through higher wages and more progressive taxation.

The way out of the “jobs versus environment” dilemma can be built through the disconnection between workers’ reproduction and capitalist productivism, reconnecting workplace and community struggles against capitalist noxiousness.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/workerist-environmentalism/