Reviving the legacy of civil rights leader Anton de Kom

- March 21, 2022

Race & Resistance

Long forgotten, Anton de Kom, Suriname’s anticolonial leader, people’s historian and fighter in the Dutch resistance is now getting the recognition he deserves.

- Author

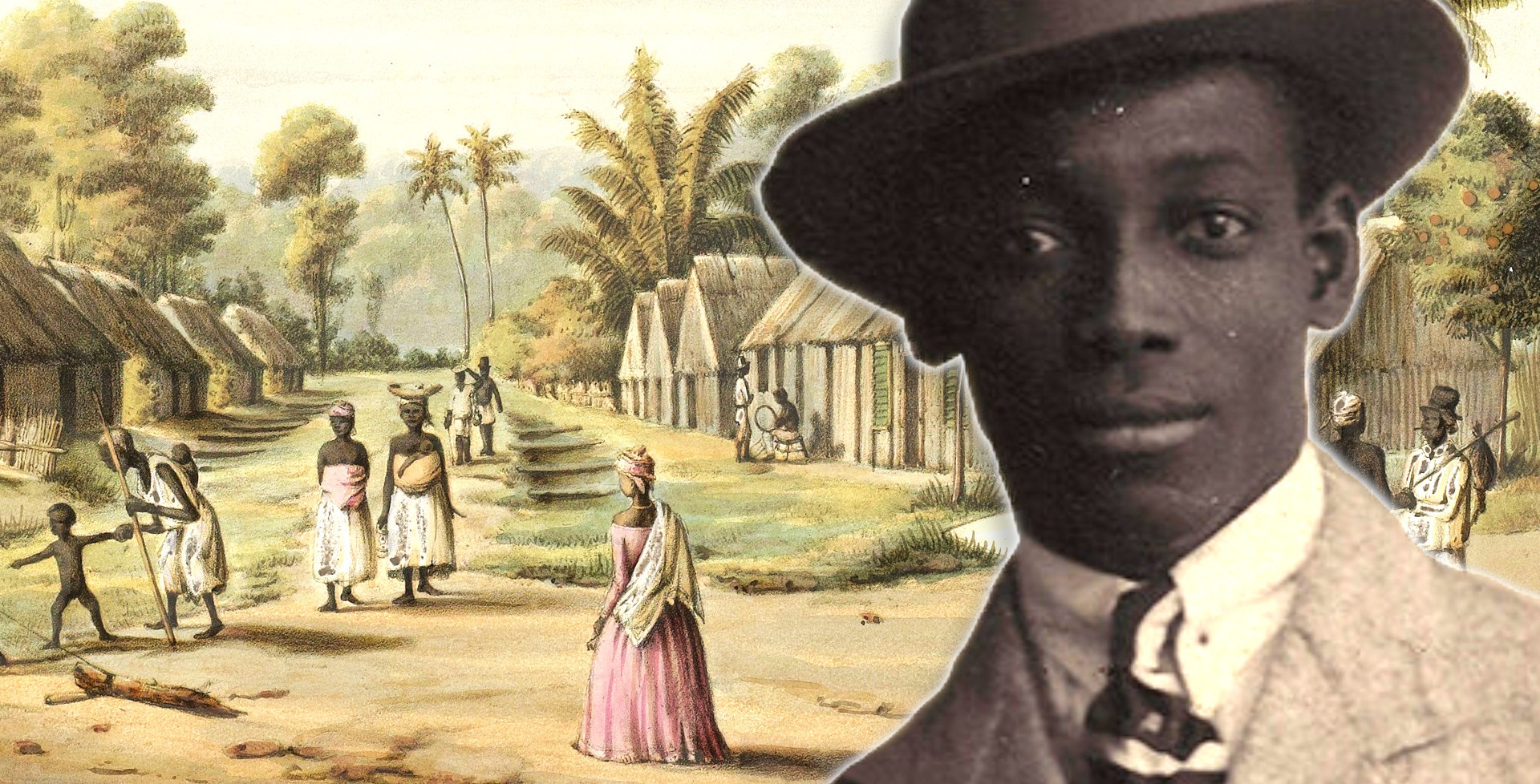

The story of Cornelis Gerhard Anton de Kom might seem one of those hard-to-believe Hollywood-style legends. Born the son of a formerly enslaved Surinamese farmer in 1898, he would go on to lead a national struggle against the ruling Dutch Empire before being imprisoned and banished to the Netherlands. Once in exile, he joined the resistance against the German occupation, was captured and died of tuberculosis in a Nazi concentration camp at the age of 47.

The seeming contradiction of a Black anti-imperialist who would come to fight and die on behalf of his oppressor nation, coupled with an unrivaled position as a Dutch colonial historian, intellectual and artist, should put De Kom among the ranks of civil rights heroes like Frantz Fanon, CLR James, Fredrick Douglas and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Until recently, De Kom’s life and works remained in relative obscurity. The first Dutch reprint of his formerly censored history of Surinamese slavery, identity and capitalism, We Slaves of Suriname, only appeared during the Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020, as an apparent indictment of the continued repression and denial in a country famed for its supposed tolerance and liberal attitudes. It is also simply an important mark of the Dutch language barrier that has trapped much of the Netherlands’ history and international relevance from view.

This year, We Slaves is published for the first time in English — nearly 90 years after its completion — and De Kom’s story and messages are beginning to enter global consciousness, replete with rediscovered artworks, children’s stories and major films in the works.

We Slaves of Suriname

De Kom’s history of Suriname is written as a poetic memoir, history, part fiction and political discourse. He paints a narrative of the country’s captivity and brutalization, the suppressed identity of its people under Dutch colonial rule and their continued exploitation following the abolition of slavery in 1863.

We Slaves is in many ways similar to CLR James’ Black Jacobins, which — also written during the 1930s — details the French slave trade in present-day Haiti and the only slave-led insurrection that brought about a Black-ruled state — which went on to become a kind of resistance manual for oppressed Afro-Caribbean communities in post-war Britain.

De Kom’s writing, however, never had such a profound influence in the Netherlands. And while We Slaves also recounts and honors numerous stories of slave revolts and resistance acts, no such successful revolution emerged in Suriname as did in Haiti. It is a tale of the unrivalled cruelty of the Dutch slave trade — something even recorded in horror by numerous French, British and Spanish slavers throughout the period.

Also similar to CLR James’ work, We Slaves gives a Marxian explanation of the causes of slavery’s abolition in Suriname. Rather than a sacrifice made by Western powers inspired by Enlightenment ideals, slavery became, for numerous reasons, unprofitable during the industrialization of the 19th century. The abolitionist movements in Europe and North America then became a convenient tool for their national rulers that allowed them to paint over an economic evolution as an ethical renaissance.

Duco van Oostrum, a senior lecturer in American literature at the University of Sheffield, emphasizes that “De Kom’s analysis of slavery, abolition and post-slavery all hinges on economic analysis and a reflection of capitalism. His emphasis on the Dutch ‘koopje’ (bargain) is central and he challenges this idea of the Dutch being some kind of moral leading nation.”

The African American connection

While De Kom’s contemporary CLR James is comparatively similar in these regards, We Slaves was more inspired by African American authors such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Fredrick Douglas, whose works also use interwoven historical narrative, cultural critique, autobiographical accounts and fiction.

Van Oostrum highlights this literary style as a key driver behind De Kom’s work. In 1937, De Kom even requested help in obtaining a scholarship to study in the US.

“There is plenty of evidence that De Kom was familiar with African American movements and his desire to travel to the US,” says Van Oostrum, “and that connection is also there in the methodology of We Slaves and the challenges to ideas of national literature formation.”

“From the invocation of the American slave narrative to Du Bois’ genre busting in Souls of Black Folk to the embracing of a socialist agenda and activism, De Kom’s book challenges Dutch literary cohesion in the profound ways African American literature has challenged the idea of American literature.”

De Kom’s connection to Otto Huiswoud, a Surinamese activist regarded as the first Black member of the American communist movement, for whom De Kom wrote an article during the Harlem Renaissance, is further evidence of his ties to the African American legacy. He also later campaigned for various US civil rights cases such as the Scottsboro Boys.

Organizing against empire

The lead up to We Slaves and De Kom’s connection and involvement in African American activism was a long one. He first began learning of Suriname’s history from the stories of his aunts, who had lived in slavery, before becoming an assistant bookkeeper at a rubber company, where he witnessed with his own eyes how the exploitation of Surinamese laborers continued after the abolition of slavery.

In 1920, De Kom left Suriname for the Netherlands, where he spent a year enlisted in the Dutch military as a cavalryman. After his post, De Kom became a bookkeeper again, this time in The Hague, and began to conduct further research into Surinamese history. It was during this period, in the late 1920s, that De Kom also began mixing with left-wing activists, writing groups and protestors — many of them Indonesian resistance groups spreading propaganda against the Dutch Empire.

He found a huge lack of resources and organization for a Surinamese independence struggle, particularly in comparison with that of Indonesia. De Kom began to redress this gap, writing articles for communist-sympathizing publications like Links Richten (Aim Left) and preparing detailed investigations for a manuscript that would later become We Slaves.

The return to Suriname

In 1932, he returned to Suriname, and upon his arrival in Paramaribo, was greeted by hundreds of local people who heard of his work and intention to subvert the country’s repressive regime. Ruling authorities had likewise got wind that a “communist agitator” was on the way and began making preparations to control what could become an uprising.

Speaking of the indentured servitude that had replaced outright slavery in Suriname, De Kom wrote: “We aim to show one thing: colored compatriots, you once were slaves, and you shall go on living in poverty and misery as long as you do not put your faith in your own proletarian unity. A smallholding here or there and a shovel or plow on credit will not help us.”

“We need a great plan of national reconstruction, a plan that includes collective corporations with modern equipment, owned by the workers of Suriname… but first, our country’s proletarians must develop class consciousness and a spirit of struggle; having thrown off their old slave chains, they must now throw off the old slave mentality.”

While De Kom was prevented from giving speeches or spreading his ideas publicly, he opened a consultancy at his father’s house in Suriname’s capital Paramaribo and was visited by a constant stream of people. Over 1500 Hindustani, Javanese, Creoles, Indians and Maroons — communities of formerly enslaved people who had escaped into the bush — visited “Papa De Kom,” and he recorded their myriad stories of abuse, poverty and trauma in a notebook.

“Every district of Suriname is teeming with malaria sufferers. Most of them are as good as dead, because they have no money… tuberculosis has become a full scale massacre,” he wrote. “Maybe I will find a way to make them [my fellows] feel some fraction of the hope and courage contained in that one powerful word I learned in a foreign country: organization.”

Arrest and banishment

These actions were too much for the local government, who began defaming De Kom and discouraging any contact with him among local people. This backfired tremendously and the number of visitors increased so dramatically that within a month the police brought the entire neighborhood surrounding De Kom’s house to a standstill.

De Kom became the target of active surveillance by the colonial authorities and anyone thought to be colluding with him was threatened by the police. De Kom refused the weapons offered by his supporters, fearing descent into armed struggle and a bloodbath. Instead, he made a vain attempt at negotiating with law enforcement, and handed himself in at a local police station. He was immediately arrested on suspicion of plotting a coup d’état, and incarcerated at the infamous Fort Zeelandia prison. His notebook containing records of local suffering disappeared.

A crowd of thousands then marched on the jail demanding his release and was dispersed by gunfire, killing two and wounding around 30 others. Without any evidence to convict De Kom of a supposed revolutionary plot, authorities secretly stowed him aboard a ship back to the Netherlands with his family. Nevertheless, state-sponsored newspapers wrote that they feared De Kom’s departure would not bring an end to the “tensions in the colony” that he had stirred.

This stint in Suriname only served to inflame the next period of De Kom’s life and works. Having seen the unremitting fear of revolution felt by the Dutch colonial rulers in Suriname, he continued to study and write voraciously in The Hague, now under constant surveillance by local intelligence agencies. Working day after day from the local library, his manuscript for We Slaves was published in 1934, less than a year after his banishment from Suriname. Two years later, a copy was translated into German, as Nazism was rapidly cementing its power throughout Europe, but the book was quickly banned by the Third Reich.

The Dutch resistance

On May 10, 1940, German bombs began falling on the Netherlands, where the local National Socialist Movement had already gained significant influence in many regions. De Kom, who had — according to some sources — fallen into depression due to unemployment and marginalization, started to become active in the resistance against the Nazi occupation of the country.

He wrote numerous articles for the illegal communist magazine De Vonk, unbeknownst even to his family, and distributed the publication covertly alongside other resistance fighters. Many of his writings drew comparisons between the treatment of Suriname by the Dutch and the German anti-Jewish racism. He also emphasized the connection between race and classism, writing in a piece published in 1941: “If the Nazis conquer [the country], this means the destruction of the Netherlands, Black slavery and hunger for our people, worse even than we are currently experiencing.”

Again, De Kom refused armed struggle, remembering the horrors he had heard and witnessed in Suriname, and continued to secretly spread anti-fascist propaganda. On August 7, 1944, Nazi police arrested him in the street and after searching his house and discovering his writings, interned him at a Dutch concentration camp before sending him to Sachsenhausen, a German camp for political prisoners. After several months of forced labor, he died of tuberculosis in 1945.

Continued resistance

The Suriname of today resembles much of De Kom’s. Poverty runs rife, exploitation of the land’s natural resources like gold and crude oil by Western and Chinese companies pollutes the natural environment and poisons the population. The Surinamese community in the Netherlands also continues to face bigotry and marginalization.

However, De Kom’s work and legacy has lived on in many powerful ways, despite a dearth of international recognition. Suriname’s national university is named after him, Amsterdam has a square and statue honoring him, and his story was recently introduced into the Netherlands’ national curriculum.

These small triumphs, evidently, have taken decades to accomplish. Some years after his death, his surviving contemporaries — namely Otto Huiswoud and his wife — established the Vereniging Ons Suriname (“Our Suriname Association,” VOS) in Amsterdam, which brought together immigrants to organize and resist the oppression faced by their community.

The VOS began keeping records of police brutality against Surinamese people in the Netherlands and published a magazine titled Adek, after De Kom. The records can now be seen in a thick notebook of newspaper cuttings kept at the Black Archives in Amsterdam. Among the clippings are three marked articles — the only records where charges were ever brought against law enforcement in decades of abuse.

Also among the over 10,000 books kept at the archives are records of how Dutch authorities purposefully segregated and housed Surinamese communities in disparate locations to prevent organization upon their arrival during the 1970s, when over half of Suriname’s entire population emigrated to the Netherlands seeking freedom and opportunity from the turmoil engulfing the country as a power struggle arose in the build-up to independence from the Netherlands, which was formally granted in 1975.

The New Urban Collective

Mitchell Esajas, a Surinamese anthropologist and researcher in Amsterdam, has over the past decade sought to revitalize and continue the work of the VOS. In 2011, he co-founded the New Urban Collective, a network of students and activists striving to “decolonize” the Netherlands’ education system and offer mentoring and labor opportunities for Afro-Caribbean youth.

He says this work is essential. “I could count the number of Black professors and Black history courses at Dutch universities on one hand,” he says. “I even felt a kind of jealousy on a trip to the UK some years ago, where we saw the level of organization among Black communities, and we want the same for the Netherlands.”

Esajas and his comrades founded BlackLivesMatter NL following the murder of George Floyd and organized demonstrations against institutional racism in the US and Europe. While thousands came out to demonstrate, Esajas’ perhaps most controversial moment came during his involvement in the Kick Out Zwart Piet movement — an ongoing activist group aiming to abolish the racist annual Dutch tradition of parading in blackface.

De Telegraaf, the Netherlands’ largest newspaper, branded Esajas and his compatriots’ peaceful protests the “danger of a radical agenda” despite a dangerous counter protest led by football hooligans and ultra-right-wing groups blockading a highway and making violent threats against anyone resisting the tradition. Esajas responded to the “laughable” article with a serious note: “I no longer feel safe walking alone in certain parts of the Netherlands. This is a disguised form of incitement and a call for violence against me and anti-Zwarte Piet activists.”

In 2020, the Black Archives were vandalized and murals of De Kom defaced with graffiti. Esajas says this is a clear indication of a “growing group of radicalized Dutch people who use violence to speak out on racism.” These disturbing occurrences have only added “fuel to the fire” of Esajas’ determination to continue his work in “decolonizing” Dutch society.

De Kom’s double character

Perhaps one of the central reasons for De Kom’s absence from the international canon of Black history is the same heroism that makes his story so remarkable. A resistance martyr for both his homeland and the nation that enchained and plundered it for so many centuries, there is an important difference between De Kom and the Afro-American civil rights leaders that inspired him.

Tessa Leuwsha, a Dutch Surinamese author, says this may be due to the fact that they do not have a homeland other than America. “In the Netherlands, one of the first questions people of color will be asked is: ‘Where are you from?’ Even if they were born and raised in the Netherlands. Anton de Kom will always be seen as Surinamese, although during his life his country belonged to the Netherlands,” she says.

Van Oostrum has also highlighted how De Kom sought to bridge the gap between his identities. In one passage of We Slaves, De Kom recounts meeting a white man aboard a ship whose face is covered in coal:

On the deck below me, a white stoker comes, but darker than I through the soot of the surfaces and he rushes to his stifling cabin. When he is halfway through the hold, he waves at me and the children. In the blackness of his face laugh the whites of his eyes and the white row of teeth. That, too, is the same everywhere and beautiful everywhere, the comradeship of the proletariat and their love for freedom.

Here, Van Oostrum argues, De Kom is again breaking the barriers connecting race, class and national identity, in a “very Frantz Fanon-like” way. This also extends the breadth of De Kom’s style and insight beyond the inspiration of African American civil rights leaders by foreshadowing Fanon, whose 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, explored the psychopathology of colonialism and its impact on human mentality.

The Jaguarman

Alongside the English publication of We Slaves, other art works by De Kom have been discovered and are beginning to surface. The release of a series of his children’s stories published in Dutch have now hit print, and an unfinished novel and film script were also discovered in a box at the Dutch Literature Museum.

Raoul de Jong, a journalist and novelist based in Rotterdam, has now been tasked with writing an official screenplay for a major film on De Kom’s life. In 2020, he published a novel titled Jaguarman: My Father, His Father and Other Surinamese Heroes, after — like so many other Dutch Surinamese people — having never been taught of his heritage or even hearing of De Kom.

His novel follows a mystical quest for his great-great-grandfather, who could apparently transform into a jaguar, an anthropomorphic hallmark of Suriname’s Winti religion that was banned by the Dutch. This power, De Jong is warned by his father, is a dangerous and demonic spirit spawned during slavery. Through his travels, however, De Jong learns the Jaguarman is actually a force of resistance — the same that drove what he calls the “miracle” of survival in Suriname.

In his upcoming film, De Jong also expresses his intention to bring out the vitality of Anton de Kom’s character, something largely unapparent in We Slaves. “De Kom loved to tap dance, dress up flamboyantly and socialize. This is a highly important aspect of his life,” says De Jong.

“This is not about the white and black of the Netherlands or Suriname, although these elements played a role. It is about us. We are the Jaguarman, we were born Jaguarmen. Becoming a Jaguarman is what lies in our destiny. Don’t be afraid of your superpowers. Use them. And don’t forget to dance.”

The ongoing work of organizations like the VOS, New Urban Collective and Black Archives, along with emerging Dutch language novels, an English translation and upcoming film are clear evidence that De Kom’s struggle surpassed and survived his death. The end of his life was never the end of his story, and — as De Jong puts it — he won, even if only posthumously.

In the coming years, it seems De Kom will take his rightful place as an international civil rights hero, while the Netherlands continues to struggle with the divisions and oppressions that “Papa de Kom” sought to expose and reconcile.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/reviving-legacy-anton-de-kom/