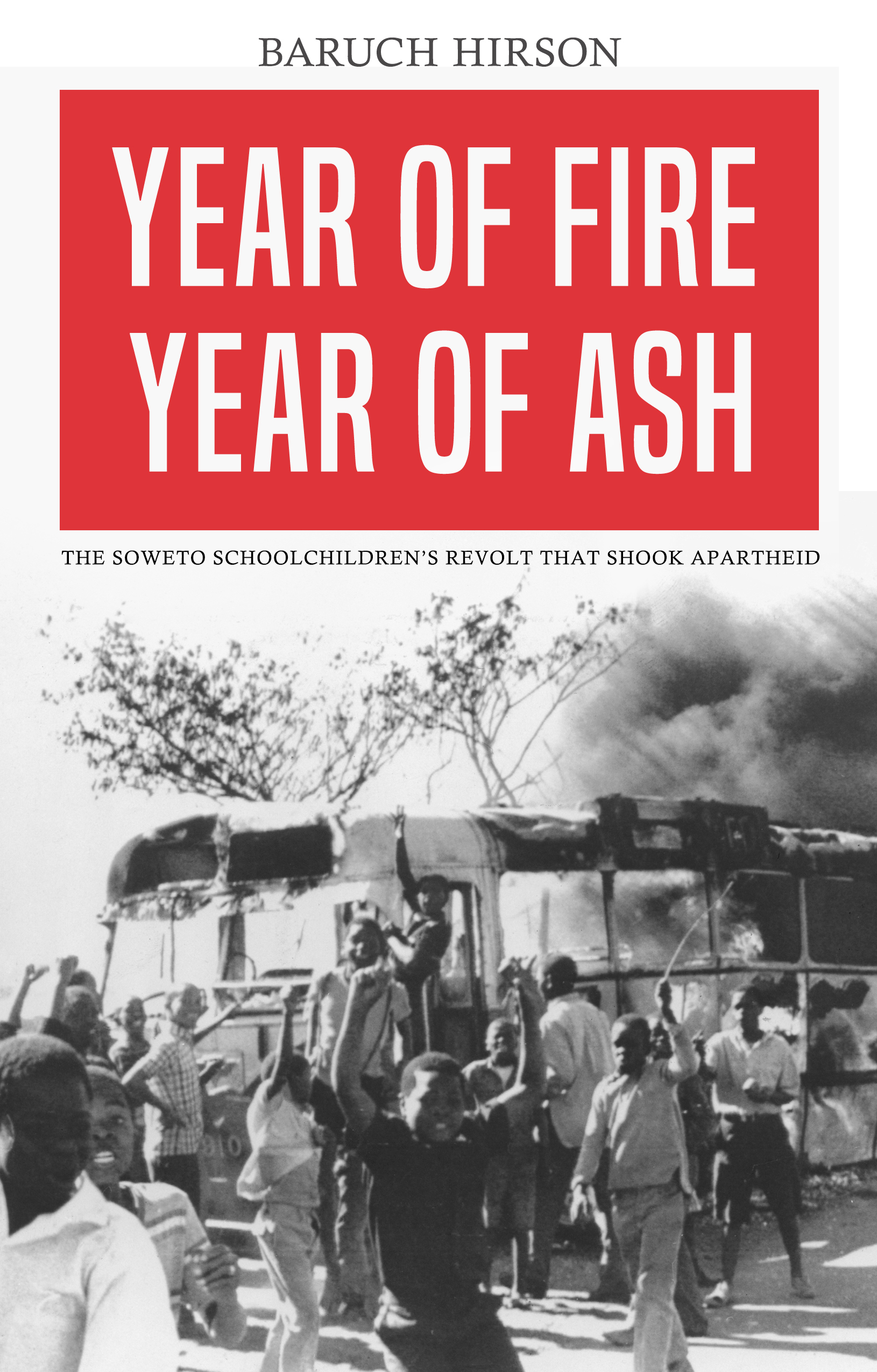

The Soweto schoolchildren’s revolt that shook apartheid

- June 16, 2016

Education & Emancipation

Forty years after South Africa’s Soweto Uprising, Baruch Hirson’s account still provides inspiration for anti-colonial and anti-capitalist struggles today.

- Author

In this exclusive extract from Year of Fire, Year of Ash: The Soweto Schoolchildren’s Revolt that Shook Apartheid, re-published this month by Zed Books (US/World), Baruch Hirson describes the socio-political and economic backdrop to the 1976 Soweto Uprising, which kicked off exactly forty years ago today.

Tens of thousands of school children took part in the uprising that started off as a protest against the proposed introduction of compulsory tuition in Afrikaans, which was widely seen as yet another discriminatory measure against the country’s black students who already suffered from a lack of educational facilities and poor-quality education. Hundreds of students — exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range from 176 to 700 — were killed when the police brutally cracked down on the protests.

The uprising is commemorated to this day, and celebrated as Youth Day in South Africa.

Black anger against white domination has never been far below the surface in South Africa. In the countryside, on the farms, and in the towns, Africans have voiced their protests, organized campaigns, and used every means available to them in order to secure some concessions from the white ruling class. At every turn they were met by an intransigent minority which meant to maintain its control — by political hegemony, by economic subordination, by social segregation, by rules and regulations, and ultimately by brute force.

The anger has often been muted. The forms of protest have been “peaceful”. The black population has shown a measure of self-control which belied the deep hatred of endless humiliation felt by every man, woman and child. In all the strikes, the boycotts, the demonstrations, and local and national campaigns, leaders urged restraint — and the police answered with baton charges, or with armored cars, teargas and bullets.

The violence, all too often, turned inwards, and in the black townships that bordered the all-white towns, groups of tsotsis (as the delinquents were called) terrorized the population. The seething anger, fostered by poverty and frustration, exacted its toll of injured, mutilated and murdered from the oppressed black population itself.

Soweto, a town that is not to be found on most maps, has been the focus of much violence for several decades now. Its population of 1.3 million serves the half million whites (who constitute the “official” population of Johannesburg) as laborers in their homes, shops and factories. By all accounts this town that is not a town, this area known to the world by the acronym Soweto (South West Township) is one of the most violent regions on earth. One year before Soweto erupted in revolt the newspaper of the students of the University of the Witwatersrand reported that:

… In the last year there was a 100 per cent increase in crimes of violence: 854 murders; 92 culpable homicides; 1,828 rapes; 7,682 assaults with intent to do grievous bodily harm. Four hundred thousand people in Soweto do not have homes. The streets and the eaves of the churches are their shelter. The faces and bodies of many Soweto people are scarred; the gun is quick and the knife is silent.

The same black fury has been turned against whites. Not only in acts of “crime” — the houses of white Johannesburg are renowned for their rosebushes and for their burglar-proofing! — but through acts of violence directed against any individual seen to be harming members of the township population. There is a long history of rioting following motor, train or bus accidents in which Africans have been injured or killed. The fury of the crowd that collected was directed against persons who were present, or passing the scene. Voluble fury changed to stone throwing and the destruction of property. The crowd would metamorphose into a seething furious mass that sought revenge.

This violence was endemic in a country where local communities lived under intolerable conditions. There was always a deep sense of frustration and alienation inside the townships or segregated areas of the big urban conurbations. The riots served to bring a section of the community together; to fuse disparate individuals into a collectivity which rose up against long- standing wrongs.

When the riot was protracted — as it was in 1976 — the crowd was not static. Factions emerged and formulated new objectives. There was not one crowd, but an ever-changing mass of people who formed and reformed themselves as they sought a way to change social conditions. To describe the participants and their groups as being “ethnic” or “tribal” or “racial”, as many white South Africans do, does not help to explain the aspirations of such people or the causes of events. It only hides the glaring inequalities in the society and conceals the poverty of the rioters. Such descriptions, furthermore, distract attention from the provocateurs who egged the “rioters” on, and from the prolonged campaigns of hatred in the local or national (white) press which often preceded African attacks on minority communities. An openly anti-Indian campaign in the press preceded the Durban riots of 1949. Direct police intervention and direction accompanied the “tribal” assaults during the Evaton bus boycott in 1956. Open police incitement led to attacks on Soweto residents by Zulu hostel dwellers in 1976.

When apologists for the system found that descriptions of the rioters in terms of “race” or “ethnicity” were not convincing, they tried another ruse. They claimed that the events were due to “criminal elements” and to township tsotsis. They ignored what has long been a marked feature of periods of high political activity in the townships of South Africa, namely a corresponding sharp drop in criminal activity. This decline in criminality was also a marked feature of the events of 1976 when the initial riots were transformed into a prolonged revolt against the white administration.

It was necessary for the police and the regime to mask the new antagonisms that emerged in the townships. When the youth turned against members of the township advisory council (the Urban Bantu Council or UBC), or against African businessmen and some of the priests, the authorities blamed the tsotsis; when the youth destroyed the beerhalls and bottle stores, again it was the tsotsis who were to blame; and when plain clothes police shot at children, tsotsis were blamed again. Yet never once did any of these tsotsis shoot at the police, or indeed at any white. Not one of the slanderers, who glibly accused blacks of shooting their fellows in the townships, find it necessary to comment on this anomaly.

Race Riots or Class War?

The revolt, presented to the world by the media as a color clash, was, in fact, far more than a “race war”. The words used in the past had changed their meanings by 1976. The word “black” was itself diluted and extended. During the 1970s the young men and women who formed the Black Consciousness Movement recruited not only Africans, but also Colored and Indian students and intellectuals. During the 1976 Revolt the Colored students of Cape Town, both from the (Colored) University of the Western Cape and from the secondary schools joined their African peers in demonstrations, and faced police terror together with them.

In the African townships there were also indications that the Revolt transcended color considerations. In Soweto there were black policemen who were as trigger-happy as their white counterparts; there were also government collaborators in the black townships who threatened the lives of leading members of the Black Parents Association; there were black informers who worked with the police; there were Chiefs who aimed to divert the struggle and stop the school boycott; and there was an alliance between members of the Urban Bantu Council, the police, and tribal leaders which was directed at suppressing the Revolt; and, ultimately, there was the use of migrant laborers against the youth. Armed, directed, and instructed by the police, these men were turned loose on the youth of Soweto, and in Cape Town, shebeen (pothouse) owners used migrant laborers to protect their premises. The result was widespread maiming, murder, and destruction of property.

Despite this evidence of co-operation by part of the African petty bourgeoisie and others with the government, there was one indubitable fact. The Revolt did express itself in terms of “black anger” which did in fact express a basic truth about South African relationships. Capital and finance are almost exclusively under white control. Industry and commerce are almost entirely owned and managed by whites. Parliament and all government institutions are reserved for whites, and all the major bodies of the state are either exclusively manned by, or controlled by, white personnel.

The conjunction of economic and political control and white domination does divide the population across the color-line. Those blacks who sought alliance with the whites naturally moved away from their black compatriots and allied themselves to the ruling group. Certain others were cajoled or threatened, bribed, driven — or just duped — into buttressing the state structures and using their brawn-power to break black opposition.

Because most white workers, irrespective of their role in production, sided so overwhelmingly with the white ruling class, class divisions were concealed, and racial separation and division appeared as the predominant social problem. The economic crisis of 1975, in part a result of the depression in the West and the fall in the price of gold, and in part a manifestation of the crisis in South African capitalism, only cemented the alliance of white workers and the ruling class. The black communities found few friends amongst the whites in the aftermath of the clash of June 16, 1976. Those whites who demonstrated sympathy with the youth of Soweto were confined to a handful of intellectuals who came mainly from the middle class; or from a group of committed Christians who had established some ties with the groups that constituted the Black Consciousness Movement.

Capitalist production in South Africa owes its success to the availability of a regimented cheap labor force. In the vast rural slums, known as Reserves, the women and children, the aged, the sick and the disabled eke out a bare existence. All rely on the remittances of their menfolk in the towns. The accommodation in townships, in hostels, or in compounds (barracks) is likewise organized in order to depress African wage levels. At the same time, the vast urban slums, of which Soweto is by far the largest, were planned in order to ensure complete police and military control, were the administrative system ever to be challenged.

The government also sought to control more effectively the vast conurbations that grew up on the borders of the “white” towns by dividing the townships, the hostels, the compounds and all the subsidiary institutions (like schools and colleges) into segmented “tribal” regions. It also divided Africans from Coloreds, and both of these from Indians, by setting up residential “Group Areas” (each being reserved for one “ace”). The map of South Africa was drawn and redrawn in order to seal off these communities, and ensure their separation from one another.

For much of the time the government has, in fact, been able to use its vast administrative machinery (reinforced by massive police surveillance) to keep opposition under control. Time and again small groups, organized by the movements in exile, were uncovered and smashed. Political organizations in the townships were not allowed to develop, following the shootings in Sharpeville and Langa in 1960, and the banning of the two national liberation movements (the African National Congress and the Pan-Africanist Congress). It was only with great difficulty that political groups emerged at a later date, and it is some of these which will be discussed in this book.

The Uprising of June 1976

Conflicts on the campuses in the 1970s coincided with a contraction of the country’s economy and with momentous events on the northern borders of the country. The fighting in Namibia, the collapse of the Portuguese army in Mozambique, the move to independence in Angola and the resumption of guerrilla warfare in Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) all influenced the youth of South Africa (or Azania, as they renamed the country). The BPC (Black Peoples Convention) generally, and SASO (South African Student Organization) groups in the universities, used more militant language. They now talked of liberation, and of independence; they defied a government ban on meetings, and when arrested were defiant in court.

When the government finally took steps to change the language of instruction of higher primary and secondary school students in 1975, the stage was set for a massive confrontation. The factors sketched above were by no means independent of each other. The strains in the South African economy, the wave of strikes, the new military situation, the resurgence of African political consciousness and the rapidly altering position in the black schools, were all interconnected.

The only non-tribal political organization that was able to operate openly inside South Africa was the Black Peoples Convention. Yet from its inception in 1972 the difficulties it faced were insuperable. The South African state was powerful, its army undefeated and unshakably loyal to the regime. The police force was well trained and supported by a large body of informers in the townships — and it had infiltrated the new organizations. Above all, the regime had the support of the Western powers and even seemed to be essential to America and Great Britain in securing a “peaceful” solution to the Zimbabwean conflict.

The young leaders of SASO and of the BPC were inexperienced. Their social base was confined (at least as of 1975) to the small groups of intellectuals in the universities, some clerics, journalists, artists, and the liberal professions. Furthermore, their philosophy of black consciousness turned them away from an analysis of the nature of the South African state. They seemed to respond with the heart rather than with the mind. They were able to reflect the black anger of the townships — but were unable to offer a viable political strategy.

At times, in the months and even weeks before June 16, the students in SASO seemed to be expecting a confrontation with the forces of the government. They spoke courageously of the coming struggle — but made no provision for the conflict. Even when their leaders were banned or arrested there did not seem to be an awareness of the tasks that faced them and when, finally, the police turned their guns on the pupils of Soweto schools and shot to kill, there were no plans, no ideas on what should be done. Black anger was all that was left; and in the absence of organization, ideology or strategy, it was black anger which answered the machine guns with bricks and stones.

The people of Soweto had to learn with a minimum of guidance, and they responded with a heroism that has made Soweto an international symbol of resistance to tyranny. Young leaders appeared month after month to voice the aspirations of the school students — and if they were not able to formulate a full program for their people, the fault was not theirs. A program should have been formulated by the older leaders — and that they had failed to do. In the event, the youth fought on as best they could — and they surpassed all expectations.

Despite all the criticisms that can be leveled against the leaders of the school pupils, the revolt they led in 1976-’77 has altered the nature of politics in South Africa. Firstly it brought to a precipitate end all attempts by the South African ruling class to establish friendly relations with the leaders of some African states, and it has made some Western powers reconsider the viability of the white National Party leaders as their best allies on the sub-continent. Secondly it marked the end of undisputed white rule, and demonstrated the ability of the black population to challenge the control of the ruling class.

In every major urban center and in villages in the Reserves, the youth marched, demonstrated, closed schools, stopped transport and, on several occasions, brought the entire economy to a halt.

The youth showed an ingenuity that their parents had been unable to achieve. They occupied city centers, they closed alcohol outlets, they stopped Christmas festivities. At their command the schools were closed, the examinations were boycotted, and the teachers resigned. They forced the resignation of the Soweto Urban Bantu Council and the Bantu School Boards — both long castigated as puppets of the regime. They were even able to prevent the immediate implementation of a rent rise in 1977 and, in the many incidents that filled those crowded days that followed the first shootings of 16 June 1976, they were able to show South Africa and the world that there was the will and the determination to end the apartheid system.

Year of Fire, Year of Ash The Soweto Schoolchildren’s Revolt that Shook Apartheid (Zed Books, 2016) is available now. Click here for distribution in the US, and here for the rest of the world.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/1976-soweto-uprising-south-africa/