Protest for Eric Garner and Michael Brown in Seattle. Photo: Scottlum

From charity to solidarity: a critique of ally politics

- January 11, 2016

Race & Resistance

Ally politics wrongly suggests that one’s privilege can only be undermined by giving up one’s role as an individual, and following the lead of the oppressed.

- Author

The liberal concept of allyship is embedded in a rights-based discourse of identity politics. It works with the ideas that there are fixed groups of people (black people, women, gay people, and so on) that have been wronged by the structural oppressions of our society, that we must work across these differences to achieve equality for all, and that this responsibility falls especially on those who most benefit from structural oppressions. It centers on the idea that everyone has different life experiences that are shaped by our perceived identities, and so if you have an identity that is privileged in our society, you cannot understand the experiences of someone with an identity that is oppressed.

According to ally politics, in order to undermine whatever social privileges you benefit from, you must give up your role as a primary actor and become an ally to the oppressed. A good ally learns that if you can never understand the implications of walking through this world as an oppressed [fill in the blank with a person on the receiving end of a specific oppression], the only way to act with integrity is to follow the leadership of those who are oppressed in that way, support their projects and goals, and always seek out their suggestions and listen to their ideas when you are not sure what to do next.

It starts to get real complicated, real fast, however, as you discover that there is no singular mass of people of color—or any other identity-based group—to take guidance from, and that people within a single identity will not only disagree about important things but also will often have directly conflicting desires.

In an attempt to find brown folks to take direction from, white folks often end up tokenizing a specific group whose politics most match their own. “What does the NAACP, Critical Resistance, or the Dream Team think about X?” Or they search out the most visible “leaders” of a community because it is quicker and easier to meet the director of an organization, minister of a church, or politician representing a district than to build real relationships with the people who make up that body.

This approach to dismantling racism structurally reinforces the hierarchical power that we’re fighting against by asking a small group to represent the views of many people with a variety of different lived experiences. When building an understanding of how to appropriately take leadership from those more affected by oppression, people frequently seek out such a community leader not simply because it’s the easiest approach but also because—whether they admit it or not—they are not just looking to fulfill the need for guidance; they are seeking out legitimacy, too.

In gaining an anti-oppression education, you learn how you benefit from the oppression of others because our society values certain identities. You must come to terms with the fact that you are granted privilege in our society simply because of what you look like or where your family comes from—and there is nothing you can do to fully refuse or redistribute your privilege. The knowledge of this often comes with a deep sense of white guilt. It can be paralyzing to know that you are given something that others will never have, though you have done nothing for it, and have no power to change this privilege.

This sense of guilt, coupled with the idea that the only ethical way to act is by taking direction from others, can make one feel powerless and debased. The model of ally politics puts the burden of racism exclusively onto white folks as an intentional flipping of the social hierarchies, while being clear that you can never escape this iniquity, but offering at least a partial absolution if you can follow the simple yet narrowly directed penance: Listen to people of color. Once you’ve learned enough from people of color to be a less racist white person, call out other white people on their racism. You will still be a racist white person, but you’ll be a less racist white person, a more accountable white person. And at least you can gain the ethical high ground over other white people so you can tell them what to do. Time and time again, we’ve seen that the salvation model doesn’t move us in a liberatory direction—only toward increased self-righteousness and plays for power.

To be an ally is to shirk responsibility for your own actions—legitimizing your position by taking the voice of someone else, always acting in someone else’s name. It’s a way of taking power while simultaneously diminishing your own accountability, because not only are you hiding behind others but you’re also obscuring the fact that you’re in control of making the choices about who you’re listening to—all the while pretending, or convincing yourself, that you’re following the leadership of a nonexistent community of people of color or that of the most appropriate black voices. And who are you to decide who the most appropriate anything is? Practically, then, it means finding a black voice who agrees with your position to justify your own desires against the desires of other white people—or mixed-race groups.

(…)

I frequently hear from anti-authoritarian “white allies” that they are working with authoritarian or nonpartisan community groups, sometimes on projects they don’t believe in, because the most important thing is that they follow the leadership of people of color. The unspoken assertion is that there are no anti-authoritarian people of color—or none who are worth working with. Choosing to follow authoritarian people of color in this way invisibilizes all the anarchist or unaligned people of color who would be your comrades in the fight against hierarchical power. Obviously, there is at least as broad a range of political ideologies in communities of color as there are in white communities.

Anarchists and anti-authoritarians clearly differentiate between charity and solidarity—especially thanks to working with 74 indigenous solidarity movements and other international solidarity movements—based on the principles of affinity and mutual aid. Affinity is just what it sounds like: that you can work most easily with people who share your goals, and that your work will be strongest when your relationships are based on trust, friendship, and love. Mutual aid is the idea that we all have a stake in one another’s liberation, and that when we can act from that interdependence, we can share with one another as equals.

Charity, however, is something that is given not only because it feels like there is an excess to share but also because it is based in a framework that implies that others inherently need the help—that they are unable to take care of themselves and that they would suffer without it. Charity is patronizing and selfish. It establishes some people as those who assist and others as those who need assistance, stabilizing oppressive paradigms by solidifying people’s positions in them.

Autonomy and self-determination are essential to making this distinction as well. Recognizing the autonomy and self- determination of individuals and groups acknowledges their capability. It’s an understanding of that group as having something of worth to be gained through interactions with them, whether that thing is a material good or something less tangible, like perspective, joy, or inspiration. The solidarity model dispels the idea of one inside and one outside, foregrounding how individuals belong to multiple groups and how groups overlap with one another, while simultaneously demanding respect for the identity and self-sufficiency of each of those groups.

The charity and ally models, on the other hand, are so strongly rooted in the ideas of I and the other that they force people to fit into distinct groups with preordained relationships to one another. According to ally politics, the only way to undermine one’s own privilege is to give up one’s role as an individual political agent, and follow the lead of those more or differently oppressed. White allies, for instance, are taught explicitly to not seek praise for their ally work—especially from people of color— yet there is often a distinctly self-congratulatory air to the work of allyship, as if the act of their humility is exaggerated to receive the praise they can’t ask for. Many white allies do their support work in a way that recentralizes themselves as the only individuals willing to come in and do the hard work of fighting racism for people of color.

Where ally politics suggest that in shifting your role from actor to ally you can diminish your culpability, a liberatory or anarchist approach presumes that each person retains their own agency, insisting that the only way you can be accountable is by acting from your own desires while learning to understand and respond to the desires of other groups. Unraveling our socialized individualization until we can feel how our survival/liberation is infinitely linked to the survival/liberation of others fosters interdependence, as opposed to independence, and enables us to take responsibility for our choices, with no boss or guidance counselor to blame for our decisions.

For a liberating understanding of privilege, each of us must learn our stake in toppling those systems of power to recognize how much we all have to gain in overturning every hierarchy of oppression. For many people, this requires a shift in values. A rights-based discourse around equality would lead us to believe that we could all become atomized middle-class families of any race who are either straight or gay married. But anyone who’s been on the bottom knows there’s never enough room for everyone on the top—or even in the middle. A collective struggle for liberation can offer all of us what we need, but it means seeking things that can be shared in abundance—not those things that are by definition limited resources.

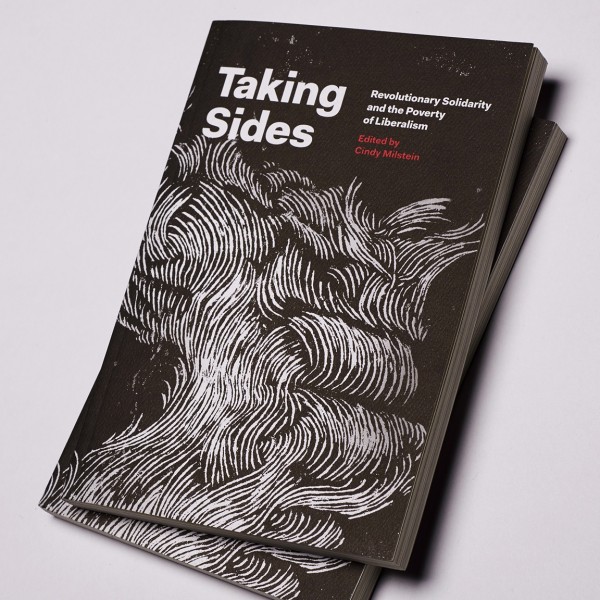

This is an excerpt from ‘A Critique of Ally Politics’, a chapter in the book Taking Sides: Revolutionary Solidarity and the Poverty of Liberalism, edited by Cindy Milstein and published by AK Press in 2015. Milstein has brought together a great collection of essays, some of which came to live as zines or direct interventions in debates and struggles, and all of which together form an invaluable resource for anarchists and activists.

From the Indigenous Action Media Collective’s contribution (‘Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex’) to Cindy Milstein’s own articles, this book reflects on ongoing struggles and offers tools and tactics for resistance. In particular the book attacks all that stands in the way of abolishing hierarchical power structures, from ‘white supremacy’, ‘peace policing’, and the role of NGO’s, to the perverse ideology of ‘ally politics.’

This analysis of ally politics “emerged from reflections on recent struggles in Durham, North Carolina, and was originally published as a zine in 2013 under the title Ain’t No PC Gonna Fix It, Baby.”

Click on the image below to buy your own copy directly from AK’s website.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/ally-politics-racism-solidarity-critique/