Policing the borders of anti-Asian violence

- April 29, 2021

Race & Resistance

Amidst calls for militarized state “protection,” it is urgent we expand the concept of anti-Asian violence towards a systemic and global diagnosis of imperialism.

- Author

This is New York City, not Vietnam!

That is how Le My Hanh, a high school student in Queens, New York, reportedly appealed to the man who had followed her into her Queens apartment building, tied her up in a vacant apartment, and accused her of being a Vietcong. That man was Louis Kahan, a 30-year-old ex-Marine and Vietnam veteran who later claimed that the New York heat and construction rubble had triggered memories of his time on the frontlines.

Le’s brutal rape and murder at the hands of Kahan in 1977 collapsed the neat spatial segregation between violence “abroad” and “at home.” Le had been marked by the US for the good life, having been resettled during the fall of Saigon and the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam in 1975. The Saigon-born daughter of a Vietnamese professor and an honor roll student at New York’s Jamaica High School, the apparent success story of Le’s resettlement served as a symbolic vindication of the US wars in Southeast Asia and a testament to the freedoms to be found in American society.

But in the eyes of her murderer, she was just another “gook” to be subjected to the same policy of indiscriminate violence which Kahan had been indoctrinated to exercise abroad. In the face of the raw racial hatred of a disturbed veteran, the US state’s sophisticated scaffolding which delineated a burgeoning refugee “model minority” at home and dehumanized “enemy combatants” abroad fell apart.

In a nonjury trial, Kahan was found “not responsible by reason of mental disease or defect” for Le’s tragic murder. By chalking up Le’s murder to the paranoid delusions of a traumatized veteran, the criminal justice system and mainstream media deferred a broader reckoning with the policy of institutionalized dehumanization that had governed US military violence in Southeast Asia. Official delineations between war and refuge, enemy and ally, and “gook” and refugee required painting Kahan as an exception rather than the rule. Kipling’s old axiom had been updated for an era of permanent war and multiculturalism: Vietnam was Vietnam, New York was New York, and never the twain shall meet.

This official distinction between institutionalized military violence in Asia and individualized racial “hate” domestically continues to constrain attempts to understand and challenge the roots of anti-Asian violence. More than one year of racist attacks and harassment stoked by pandemic racism, coupled with the targeted murders of six Asian women in Atlanta and four Sikh community members in Indianapolis, has brought newfound political visibility to the persistence of anti-Asian racism. Yet popular framings such as the hashtag “#StopAsianHate” obscure the institutional and international roots of anti-Asian violence in favor of a liberal vision of domestic civil rights enforcement and “raising awareness” to combat individual prejudice.

The domesticating of anti-Asian “hate” enables a strange contradiction: the relative visibility of anti-Asian violence in the US has been accompanied by the quiet expansion of the US military footprint in Asia, a bipartisan inheritance of Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and the virulent China-bashing of the Trump era. To insist on the link between the two is to challenge the state’s self-designation as the face of anti-racist enforcement rather than racism’s institutionalized form. Such connections are obscured by the dominant lens of liberal anti-racism, which is increasingly used to naturalize the role of repressive state apparatuses — from local police presences to international military buildups — to “protect” targeted Asian and Asian American communities.

At a time when the US simultaneously targets the “Indo-Pacific” as its primary military theater and pledges itself to the defense of Asian American communities, the critique of empire emerges as the connective tissue necessary to reject these carceral discourses of state protection. Rising abolitionist, anti-imperialist calls for self-determination and community-based visions of safety and solidarity demand that we expand the conceptual borders of anti-Asian violence towards a systemic and global diagnosis of militarism, imperialism and racism.

A different timeline of anti-Asian violence

In a national culture steeped in amnesia and exceptionalism with regards to the Asian American experience, the so called “spike” in anti-Asian violence has sparked renewed attempts to historicize the roots of this racism. Donald Trump’s “China virus” rhetoric quickly prompted historical comparisons to 19th century associations between Chinese migrants and disease. Graphic footage of street violence against unsuspecting Asian victims sparked invocations of Vincent Chin, the Chinese American groom-to-be bludgeoned to death in Detroit in 1982 by two white men who saw in Chin’s East Asian face a proxy for the Japanese automobile industry they blamed for their declining livelihoods. Historians further alluded to precedents of vigilante and state violence against Asian Americans, naming 19th century anti-Chinese massacres such as that of Rock Springs, Colorado in 1885 and the state-sanctioned incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II.

These well-trodden timelines of anti-Asian violence reveal as much as they obscure. Generally absent from these historical accounts are events such as the 1906 Moro Crater Massacre, during which US forces killed more than 800 Filipino independence fighters before posing with their bodies in mass graves; or the My Lai massacre of 1968, when 504 Vietnamese civilians were murdered by US troops. While the March 16, 2021 murder of eight people in Atlanta, including six Asian women, brought important national scrutiny to the specific violences faced by Asian women and sex workers, mainstream media accounts largely evaded the important interventions of grassroots activists and scholars, who placed the tragedy in a global context in which Asian women are frequently the targets of gendered racial violence by US military personnel in “camptowns” in Okinawa, Korea, the Philippines and beyond.

In the early months of the pandemic, Asian American progressives roundly chastised the callous patriotism emblematized by Andrew Yang’s call to combat anti-Asian violence by “[wearing] red white and blue.” But many have nonetheless clung to conceptual borders of anti-Asian violence which place preeminence on the US nationality of its victims. In contrast, movements against imperialism and militarism in Asia have long been guided by a critique of racial violence, especially towards women in general and sex workers in particular. The murders of Yun Geum-i in Korea in 1992, Jennifer Laude in the Philippines in 2014, and Rina Shimabukuro in Okinawa in 2016 all sparked renewed national movements for demilitarization and self-determination, yet these tragedies did not spark corresponding conversations in the US about the violence this country inflicts in Asia. These silencings are not accidental but strategic, enabling the cleaving of domestic anti-racist movements from internationalist struggles against empire.

Yet at the height of the Vietnam War, it was exactly these linkages between anti-Asian racism “at home” and US imperialism abroad that Asian American anti-war activists insisted on. As Mike Murase wrote in the pages of Gidra, a radical Asian American magazine published out of Los Angeles, the racism facing Asian Americans was intrinsically linked to the war in Vietnam. Describing the need for an Asian contingent to the national anti-war rallies of May 1972, Murase argued: “The systematic dehumanization of ‘gooks’ in the military affects Asians in America as well, because it is to America that trained killers of Asians return.”

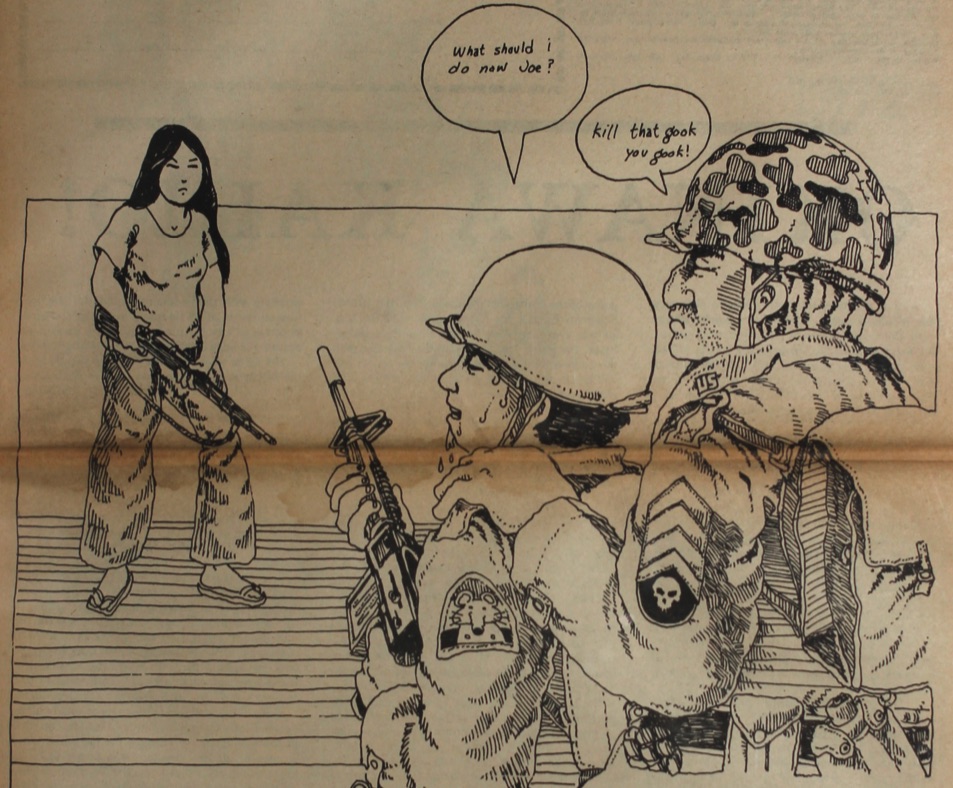

Alan Takemoto for Gidra Magazine, from the Densho Digital Archives.

In the eyes of Asian American anti-war activists, racial ideology transcended national boundaries, uniting Asian peoples in shared struggle against the myriad violences of global white supremacy. Chinatown organizer Mike Eng captured this interrelationship when he likened LAPD patrols in Los Angeles Chinatown to an occupying force abroad. Reporting in Gidra on the physical violence and racial abuse hurled by police towards Chinatown youth in the summer of 1971, Eng saw a “My Lai mentality” that had “returned home with the troops.”

In such moments of racial encounter, the Asian body served as an avatar for the transference of imperial ideologies which painted Asians as official enemies marked for destruction. An illustration by Alan Takemoto featured on the May 1972 Gidra cover crystallized the dialectics of race and imperialism in provocative terms: an Asian American soldier, confronted by what appears to be a Vietcong woman, asks his commander: “What should I do now, Joe?” The commander’s response: “Kill that gook you gook!”

Confronting an “anti-racist” empire

The conspicuous absence of US imperialism within conversations about anti-Asian racism was on full display when Secretary of State Antony Blinken took a moment during his diplomatic tour of Asia to denounce the Atlanta massacre. From a press conference in Seoul, Blinken said he was “horrified by this violence which has no place in America.” Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin similarly condemned what he called a “horrific crime.”

This imperialist hypocrisy is worth naming. Blinken’s and Austin’s Asia tour had the express aim of shoring up support for further US military buildup in the region. Lloyd’s Pentagon is rolling out a $27 billion Pacific “deterrence” initiative to expand US military bases, missile capacity and war exercises in a region the US now declares its primary theater of war. While the 20th century hot wars in Korea and Vietnam have receded into generational memory, Blinken and Lloyd inherit — and seek to expand — the infrastructure of permanent militarization those wars instantiated.

This Cold War military apparatus has swelled into an “empire of bases” with a quarter of a million US military personnel staffing over 800 official overseas military bases. Increasingly, this imperialist network is triangulated around China: even as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq raged on, Obama officials were defining the 21st century as a “Pacific century” which required a military and economic pivot to Asia to face a “rising” China. That Obama-era consensus was escalated both by the Trump administration’s declaration of China as a “strategic competitor” and the Pentagon’s “number one priority” and Biden’s bellicose campaign promise to get tough on “thugs” like Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un.

Critics have pointed out that the Atlanta shooter’s language describing Asian women as “temptations” is itself part of an imperialist discourse which paints Asian women’s bodies as part of the spoils of US war. In this context, Blinken’s and Austin’s self-righteous denunciation of anti-Asian violence stands in stark contrast to their role as architects of a global military apparatus which enables the endemic violence of US military bases in Asia. In Korea, the Philippines, Okinawa and beyond, this violence — often sexual violence — is silenced through joint status of forces agreements which protect US soldiers from being tried by local courts for violence they commit, obstructing justice for the victims of US occupation.

The ease with which figureheads like Blinken and Austin can safely denounce anti-Asian violence while advancing a historic military buildup in Asia thus speaks to the thorough excising of imperialism from popular understandings of racism. But Blinken’s claim to “stand with the Korean community and everyone united against violence and hate” in the wake of the Atlanta massacre is also illustrative of the longstanding uses of similar rhetoric of freedom, protection and deterrence to cloak the ambitions of US empire.

Blinken’s remarks inherit a longstanding paradigm of liberal war which poses the US military not as a purveyor of violence but a righteous watchdog against it. In this sense, denunciations of violence by the figureheads of imperial violence are not simply hypocritical, but paradigmatic. The conceit of US imperialism is to frame its myriad interventions and occupations not as destructive — of sovereignty, ecosystems and local livelihoods — but as productive — of freedom, liberal personhood and free market capitalism. Underpinned by a liberal discourse of defense, the bloody post-World War II order of US supremacy is rendered instead a benevolent “Pax Americana.” Historian Monica Kim describes the paradigm shift marked by the Korean War: “War would have to be conducted in the name of ‘humanity’… conducted as a disavowal of war itself.”

These militarized conceptions of freedom continue to structure US geopolitics in Asia and beyond. The Trump and Biden administrations have both advanced the concept of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” as the strategic cornerstone of US regional policy. But a declassified 2018 strategic framework document outlines just what policymakers believe “freedom” entails. The top priorities outlined for US Indo-Pacific strategy are to “preserve US economic, diplomatic, and military access,” “maintain US primacy,” and “advance US global economic leadership.” No doubt, the discourses of liberal intervention — premised as necessary defense against regional bogeymen like China and North Korea — continue to provide cover for a project of US regional hegemony.

Blinken’s promise to “stand with the Korean community” in the wake of the Atlanta tragedy thus parallels the US commitment to “defend” South Korea from its supposedly belligerent and trigger-happy northern neighbor — in contradiction to cross-border movements for peace and reunification. Both narratives position the US state not as the primary purveyor of racial violence but as a benevolent watchdog tasked with regulating “hate” in the form of either individualized prejudice or “rogue states” which challenge the US hegemonic order.

The anti-racist racial state

Unsurprisingly, Blinken’s and Lloyd’s denunciations of anti-Asian violence have been echoed by stateside officials: President Biden ahistorically described recent attacks on Asian Americans as “un-American.” Even Donald Trump was compelled to tweet in defense of Asian Americans last March, calling for the US to “totally protect” the community amidst rising hate violence stoked by his own politicization of the pandemic for the purposes of a hawkish geopolitical agenda vis-a-vis China.

While it is reasonable to press political leaders to denounce such violence, the function of this official antiracism is more circumspect. Empty state disavowals of anti-Asian “hate” serve to delink individual racist acts from their systemic corollaries: the Biden administration’s continued deportation of Southeast Asian refugees, the criminalization of sex work and the expanding US military footprint across Asia.

In this sense, liberal antiracism can be seen as the domestic complement to liberal war, in which the structure of racism itself is increasingly predicated on its own disavowal. Both discourses reinscribe the state’s responsibility to police the very violence it creates. Here, the United States’ self-designation as a “global policeman” is instructive: the “defensive” posture of US military occupation abroad mirrors renewed calls for police to “protect” Asian American communities from racial violence.

Such calls have quickly gained momentum in providing a progressive pretense to police expansion. For instance, the New York Police department formed an anti-Asian hate crimes task force in August 2020, much to the dismay of local Asian American community organizations which consider the NYPD itself a source of systemic violence which targets Asian American tenants, undocumented immigrants, sex workers and elders. Following suit, President Biden announced in March that the FBI would be giving “nationwide civil rights training events” as part of a presidential action to address anti-Asian violence. These carceral moves have less to do with keeping Asian American communities safe than with reifying the punitive state’s role as an official arbiter of anti-racism.

The police murders of Daunte Wright in Brooklyn Center and Adam Toledo in Chicago further intensify the ideological uses of promoting “anti-racist” policing to combat anti-Asian violence. Long positioned as a “racial bourgeoisie” used to discipline Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities, the simultaneous unfolding of anti-Asian hate crime task forces amidst national demands for police abolition raises the specter of wielding Asian Americans to reinforce the moral legitimacy of the police as an institution. In this divide-and-conquer scheme, the moral goodness of police tasked with “protecting” vulnerable Asian communities will be posed as a symbolic negation of the systemic violence police inflict on working class communities of color.

Once more, the linking of abolitionist and anti-imperialist critique helps us to see through these ruses of state protection and reform. While images of militarized police forces in American cities often provoke criticisms of a “war come home,” we might instead see the police and military as conjoined arms of a repressive apparatus designed to enforce the conditions necessary to sustain racial capitalism at both a domestic and global scale. These overlapping, mutually constitutive circuits of Orientalism and anti-Blackness form a regime of racial capitalism whose dismantling requires a language and lens beyond any individualized, identity-constrained vision of combating hate or prejudice.

Beyond “belonging”

In an emotional exchange last month, Ohio politician Lee Wong addressed racism against Asian Americans at a local community meeting. “People question my patriotism, that I don’t look American enough,” Wong protested. Revealing a long scar across his chest sustained during service in the US Army, Wong cried out: “Here is my proof…Is this patriot enough?”

Footage of the exchange went viral, amassing tens of millions of views on YouTube and Twitter from viewers who applauded Wong’s patriotism and service. Yet the logic that Americanness is a prerequisite to shelter from racial violence — let alone that such Americanness is best demonstrated through war — is troubling.

These claims to Asian American belonging are complicated by the historical uses of multiculturalism as a tactic of liberal war. The genre of “military multiculturalism” has long posed US militarism as a crucible of racial progress rather than an instigator of racist war. The desegregation of Army units in the Korean War, for instance, cloaked that genocidal intervention in terms of Black-white national unity. The decorated military service of all-Japanese American units in World War II similarly provided a redemptive arc to the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans.

This pernicious multiculturalism allows selective incorporation into the arms of the racial state in order to provide legitimacy to the persistence of racist systems in an era of official antiracism. Under this paradigm, the structures of the racial state may be entrenched not by a phobic exclusion but a -philic embrace. If Vietnam War commander William Westmoreland’s callous declaration that “life is cheap in the Orient” represents one register of imperial racism, Antony Blinken’s recent ode to sundubu-jjigae represents an imperialist discourse now defined less by explicit dehumanization than by a multicultural embrace of de-politicized “difference.” The apparatus of a global military empire and the violence it deals has not changed — only its enabling fictions.

The ruse of liberal antiracism takes on a new urgency in a moment in which the justifying discourses of US hegemony are faced with a crisis of legitimacy on all sides. From a catastrophic pandemic response, to the January 6 siege of the “city on the hill,” to ongoing Black abolitionist insurrections — the common sense of US moral leadership of the world is increasingly under question. In this context, official antiracism, as a legitimizing discourse of racial rule, threatens to subsume the contradictions of these crises into progressive notions of slow, benevolent reform. Depoliticized symbols of racial liberalism do this work of legitimation: Black Lives Matter banners hang from the US embassy in Seoul and are painted on the streets of Washington D.C. A Black Secretary of Defense is lauded as a figure of progress — deep ties to the weapons industry be damned. Exceptional acts of violence are denounced as “un-American” — leaving uninterrogated the structures of racism that enable them.

The renewed visibility of anti-Asian violence is a critical invitation to expand our conceptions of racial violence beyond metrics of belonging, nationality, class or kinship. To the contrary, discourses of militarized “deterrence” in Asia and local police “protection” seek to domesticate a radical critique of systemic violence in favor of a legitimizing discourse which proffers militarized state enforcement as the adjudicator of racial violence rather than its primary, constitutive form. At a time when the “Indo-Pacific” is targeted as the primary theater of US military power and “stopping Asian hate” is deployed as a mandate for state intervention in racialized communities, to return imperialism to the frame is to instead expose the inextricable global circuits of racism, imperialism and capitalism at the root of racial violence.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/anti-asian-racism-american-imperialism/