The true cost of austerity: lessons from Greece

- November 28, 2018

Capitalism & Crisis

The real lessons from Greece’s economic crisis can be learned not from the toxic legacy of austerity, but from movements for social justice and food sovereignty.

- Author

“You did it! Congratulations to Greece and its people on ending the program of financial assistance. With huge efforts and European solidarity you seized the day.” With this tweet, the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, celebrated the official ending of the third structural adjustment program on August 20, 2018. But as Greece’s “age of austerity” is consigned to history, the scars of eight years of savage cuts to wages, incomes and social spending will continue to haunt the Greek people for many years to come.

Unemployment rates in Greece reached nearly 30 percent and youth unemployment surpassed 50 percent several times during the past years, peaking at over 60 percent in 2013. Greece will continue to be subject to financial supervision by creditors, with a stipulation to maintain a 3.5 percent fiscal surplus until 2022 and a 2.2 percent surplus until 2060, belying any claims of European solidarity and effectively tying the hands of Greek governments for decades to come.

A toxic legacy

The creditors’ official narrative that painful austerity measures were implemented to “save Greece” demonstrates a failure to identify or acknowledge the real lessons of the crisis. Austerity measures have led to violations of economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to food.

A recent report by the Transnational Institute, FIAN International and Agroecopolis, documents the impacts of austerity measures on people’s access to food, and the wider food and agricultural system in Greece. Based on original fieldwork across Greece, interviews with more than one hundred people, aggregate data and survey analysis, literature reviews, legal analysis and expert commentary, the report delivers a damning blow to mainstream accounts of the Greek experience of austerity.

Analyzing the way in which waves of austerity have rippled through the food and agricultural system, it becomes clear that hardship for some has yielded untold benefits for others. This should not be surprising. The world food system is rife with structural inequalities and Greece is no different in this regard. It is unusual, however, to see these inequalities brought so starkly into relief.

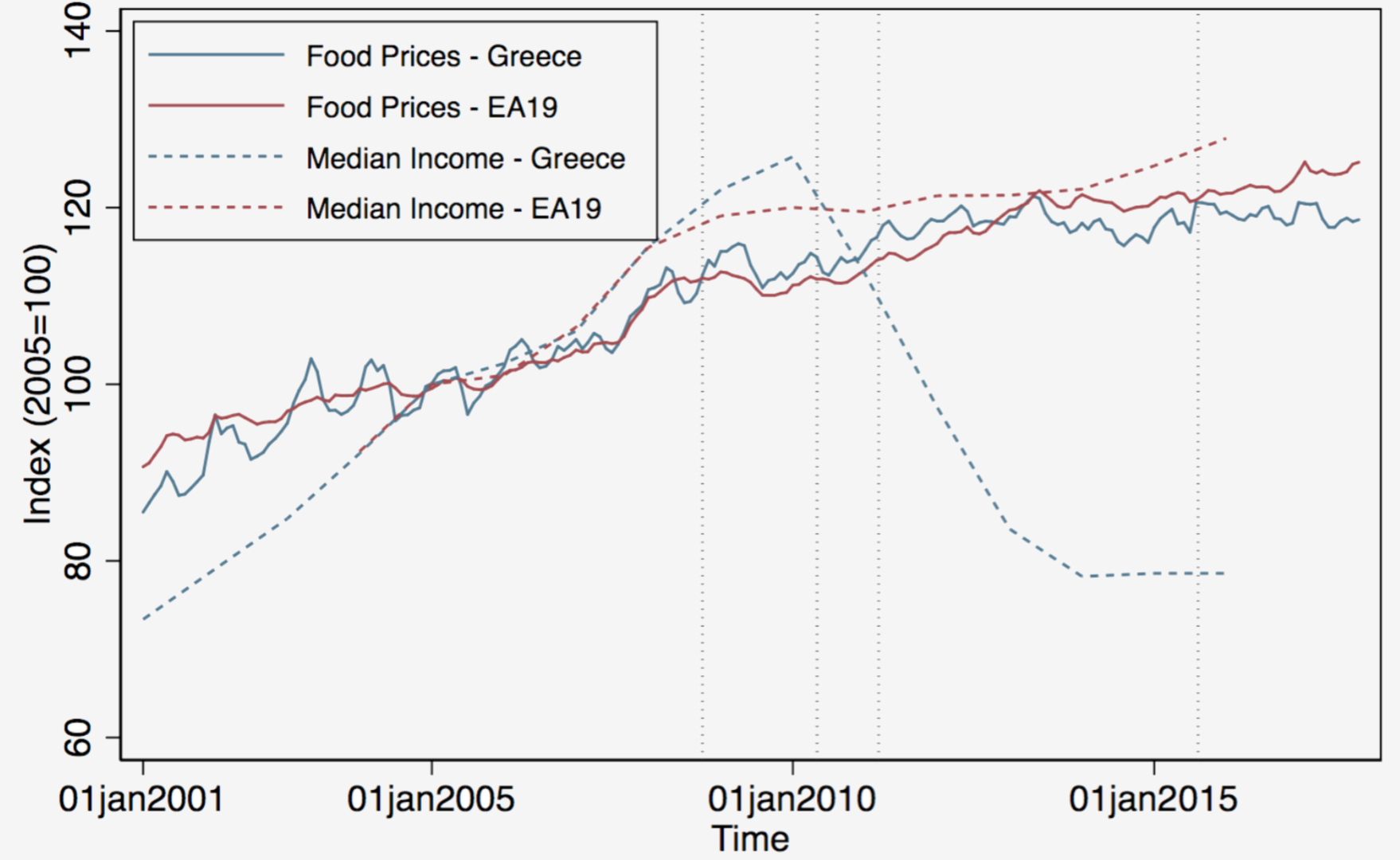

Take a look for example at the way in which food prices evolved during the crisis:

For a significant part of the crisis — until 2013 — food prices in Greece rose at an even faster rate than in the rest of the Eurozone, while incomes plummeted and labor costs were slashed. The perverse effects of austerity measures here are clear. Increases in VAT on food were introduced as part of the effort to increase tax revenue during the crisis, pushing food prices up, even in the face of declining living standards. All this against the backdrop of heavy dependence on imported food and the oligopoly power of supermarkets.

Austerity measures have favored larger food retailers and private traders to the detriment of small-scale producers as a number of structural reforms have been pursued, including the liberalization of the retail and wholesale food trade and privatization of the Agricultural Bank of Greece.

Violations of human rights

This has had serious consequences for people’s access to food. The share of households that cannot afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or vegetarian equivalent every second day has increased sharply since the beginning of the crisis, from approximately 7 percent in 2008 to more than 14 percent in 2016. There has been a discernible rise in the use of soup kitchens, food banks and other humanitarian assistance schemes. In 2016, in the prefecture of Attica alone, there were at least 200 organizations providing free meals to those in need.

Several austerity measures including changes to agricultural taxes and the drive towards privatization and trade liberalization directly undermined the right to food in Greece. Other measures such as minimum wage reductions and pension cuts also affected this fundamental human right and contravened other economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to work, housing and health.

The fallout from austerity shows there is a fundamental need to take control of the food system away from the hands of large food retailers, towards those farmers, fishers and citizens who are proposing a new food politics.

This is already happening. The “no middlemen” movement that sprang to life during the years of the crisis and which involved direct producer-to-consumer markets where food was sold at 20-50 percent below supermarket prices is one prominent example of this kind of “food sovereignty” in action.

Beyond this, all sorts of social and solidarity economy initiatives have taken off, not just around food, but also in other spheres, including social health clinics and communal housing. In 2013, 372 social enterprises were registered. By 2016 there were 907.

These are not without their own tensions and difficulties for the future, but it is from these movements for social justice, and not the toxic legacy of austerity, that the real lessons from Greece’s economic crisis can be learned.

Read or download the report, “Democracy Not For Sale”, here.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/austerity-costs-greece/

Further reading

Black revolutionary currents of the Atlantic

- Julius S. Scott

- December 4, 2018