Photo: David Goldman

Baltimore: ‘we want justice, by any means necessary’

- May 4, 2015

Race & Resistance

People had to resort to bricks and fire to be heard, but finally the authorities can no longer ignore the voices of the marginalized and oppressed.

- Author

It is not easy to sum up the history of oppression that is being expressed in these days of protests and riots in Baltimore. It becomes even more difficult when your hands are shaking with anxiety and helplessness, while right outside your window a couple of police officers are arresting a teen and the entire city is a frenzy of sirens.

But let us start from the beginning. Or not quite, as the beginning of this story is not easy to spot. Let us start with Freddie Gray. On April 12, at 8.40am, at the intersection between Presbury and N-Mount Street (in the neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester, West Baltimore), Freddie made the fatal mistake of running away from a police officer (Brian Rice) on bicycle, who had just made eye-contact with him. After deciding that this was enough of a probable cause to arrest the 25-year-old, Rice called out for the support of five other officers (Garrett Miller, Alicia White, William Porter, Edward Nero, Caesar Goodson) with whose assistance he arrested Freddie (probably already injuring him at this point) and threw his limp body into a police van.

Despite several calls for medical assistance by Freddie Gray, none of the officers responded. Instead, they dragged the victim around for 40 minutes, picking up other suspects in the meantime, before arriving at the police station. By that time Freddie was lying unconscious on the vehicle’s floor. A week later, on April 19, Freddie died in the hospital as the result of a severe spinal injury.

The death of Freddie Gray is only the latest in a long series of which we remember but a few names, such as those of Trayvon Martin (killed in February 2012) and Eric Garner (July 2014). The issue of police brutality against the black community suddenly hit newspaper headlines after the murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, last August. Mike Brown’s premature death triggered days of riots and months of protest in Ferguson and across the country, with thousands taking to the streets to declare that “black lives matter.”

The murder of Freddie Gray thus occurred in a context in which police actions are under close scrutiny of public opinion, on the one hand, and of the legislators on the other. Tensions in black-majority neighborhoods are running high. To this background we must add the fact that we are speaking about Baltimore: a city in which 65% of the population is black and where a large majority of the overall population lives in the “hoods” of East and West Baltimore, with only a very thin “safe strip” remaining in the predominantly white middle.

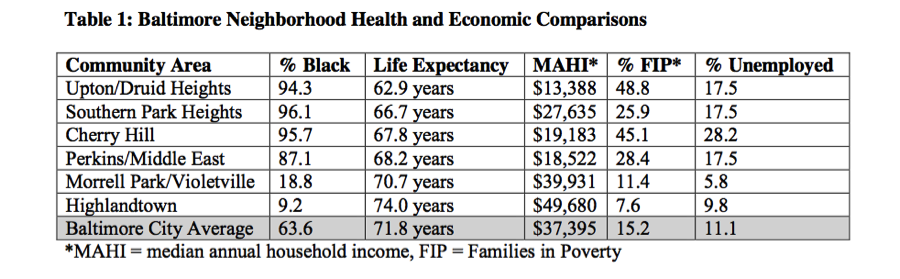

In sum, this is a tale of two cities, where the wealthy, white-majority neighborhoods of Guilford, Roland Park and Canton — with their perfectly mowed lawns — stand in stark contrast to the worn-down, crime-ridden neighborhoods that make up most of the city, where the rates of unemployment are — in the best cases — double those recorded in white neighborhoods. This is without taking into account those who have stopped actively seeking employment, which includes many young black men who are prevented from pursuing a job because they have criminal records.

Table extracted from the paper ‘Down to the Wire: Displacement and Disinvestment in Baltimore City’, by Lawrence Brown

In this context, many black youths in the hoods find that the only remaining job opportunities are in drug trafficking and the informal economy that revolves around it. The drug-dealing business is not only destroying the black community as a result of addiction, but is also producing the chain of violence that inevitably comes with the trade.

Thus, the umpteenth murder took place in a city where social tensions were already at fever-pitch, waiting to burst. In the days following Freddie’s death, Sandtown has taken to the streets every single day to protest, bringing along a growing crowd of supporters. Last Saturday, April 25, everybody was there: from Freddie’s friends to Johns Hopkins academics, from local unions to the angry mothers who have lost their husbands, their sons, their brothers at the hands of the police force: 1,500 people yelling “we want justice for Freddie!” — some at the police officials, some at the Mayor, some others at the sky.

After four hours of marching through the city, the crowd poured into the square in front of Baltimore City Hall, where the leadership of the New Black Panther Party made an attempt to keep the mass of people in place for a series of speeches. This attempt failed about half an hour afterwards, when Malik Shabbazz’s request to ‘calm down, we will let you march again in about an hour’ was met by a group of hundreds of people spontaneously “leaking” back into the streets and heading towards the stadium, where the baseball season recently started again.

Although the Baltimore police department had been almost invisible throughout the march, the stadium full of devoted Orioles fans could not go unprotected: rows of riot police equipped with horses and pepper-spray blocked the entrance. At the same time, however, it was clear that police officers received orders to stay calm, so much so that they remained relatively composed even as protesters attacked six police cars parked nearby the stadium and blocked the intersection between W-Pratt St and S-Howard St for four hours.

It was only towards 8pm that the police helicopter, which never stopped circulating overhead, began to relay the usual message: “you must clear the intersection or you will be arrested.” Even in this case, however, the authorities showed a surprising degree of restraint, clearly ordered from above: the mayor, police authorities and everybody else knew how incendiary the situation was.

But the composure displayed by the police was not enough to sedate the deep-seated anger, rooted not only in the racism and abuse of the law enforcement apparatus, but also in the lack of alternatives available to black youth in the hoods. Hence, while only 50 miles away President Obama was letting loose in a stand-up show for the annual White House correspondents’ dinner, the protesters in Baltimore went back towards the Western District, where people engaged in a night of clashes with the police.

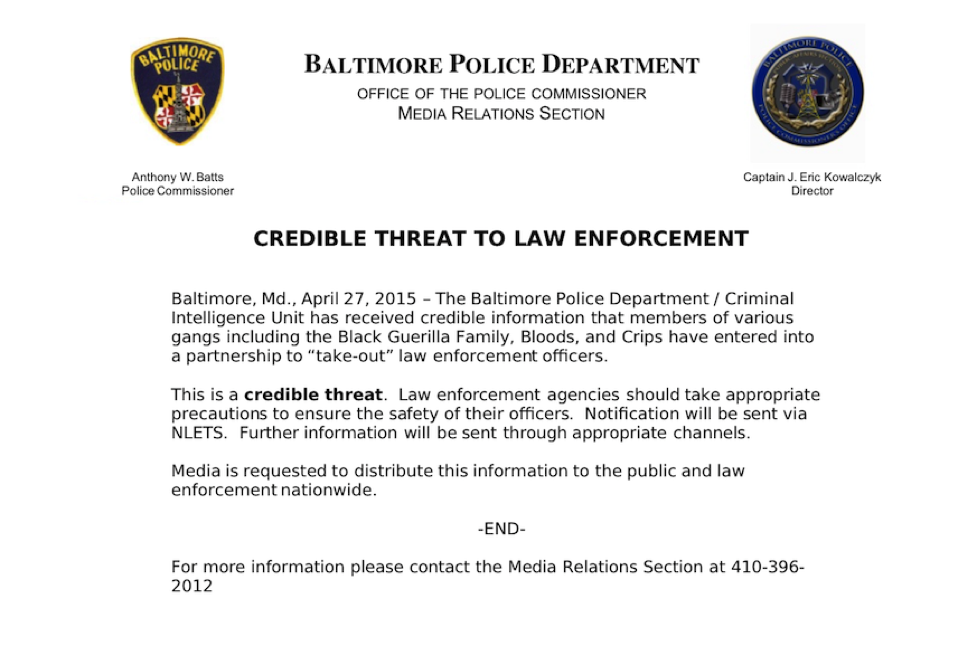

Following the night of clashes in Sandtown, the community called for peace in the streets until Freddie’s funeral, scheduled for Monday, April 27. Rallies were not to be resumed until the following Tuesday. But things soon got more complicated: April 25 saw the announcement of a truce between the three major gangs in the city: the Bloods, the Crips and the Black Guerrilla Family. While only a few days before they had still been killing each other, on April 25 the members of the different gangs were walking together in the same march, for the first time since the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, following the savage police beating of the African-American taxi driver Rodney King.

The truce is of such importance that it was invoked by the police later as a reason to abandon the low-key approach of April 25 and deploy the National Guard in the streets. On Monday morning, the Baltimore Police Department (BCPD) released a declaration stating that intelligence sources had issued a warning about a “credible threat” regarding a partnership between the city’s gangs aimed at “taking-out law enforcement officers.”

With this statement (whose validity has been questioned by the public declarations of some of the gang members involved), the authorities intended to send a clear message: we do not appreciate your unity, so be careful, as we are ready to act. The criminal economy, after all, constitutes the main relief valve of the marginalized urban underclasses, and the possibility of different criminal networks reaching common ground represents too big of a threat to law enforcement.

And so city authorities decided to first close down all public schools in the area and send the students home, and secondly to position 400 riot police nearby Mondawmin Mall, where riots were rumored to start. At this point, hundreds of school boys who had just been told to leave the nearby public school Douglass High found themselves facing off with hundreds of policemen dressed in riot gear and determined to not let anyone leave. This standoff was the immediate trigger for a long day (and night) of riots, which ended — according to estimates by the city authorities — with more than 200 arrests, 144 car fires and 15 structure fires.

In response, a state of emergency was declared across the city and the newly elected Governor of Maryland Larry Hogan called in the National Guard. Helicopters have been circling over the city 24/7 and on Tuesday, April 28, a week-long curfew was imposed, forcing everybody to stay indoors between 10pm to 5am. In the meantime, protests continue.

These are important days, not only for Baltimore, but for the entire country. People had to resort to bricks and fire in order to be heard, but finally the authorities (and the world) can no longer ignore the voices of the youth, the mothers, the fathers of Sandtown, who have much to talk about. They talk about the constant abuse of the police force and the everyday racism that consigns black people to a sub-human status. They talk about how the city authorities have completely divested from these neighborhoods, privatizing the little social housing that was left, closing down the recreation centers and cutting down water provisions to those households that cannot afford to pay the bills, while at the same time spending millions of dollars in TIFs and other subsidies to the big downtown developers.

They also talk about jobs, or more precisely the lack thereof, and the absence of perspectives for most of the black youth of Baltimore (and so many other cities in the United States). Because racism is the mask exploitation hides under. It constitutes yet another instrument to oppress marginalized communities and undermine social solidarity. Hence, in a city that has since the 1970s experienced a process of severe de-industrialization while companies fled abroad in the search for cheaper labor force, African-Americans have been consigned to poverty — either stuck in unemployment or hired for low-end jobs, predominantly in the service sector (the only sector that has expanded in the last few decades). As the first victims of the sub-prime mortgage bubble that trapped so many household into a spiral of debt, now they are also the first to be evicted from their residences to make space for the plans of the big private developers.

The protests of the past week talk about all of this — and, yes, they also talk about Freddie. We want justice, by any means necessary.

UPDATE, 02/05/2015:

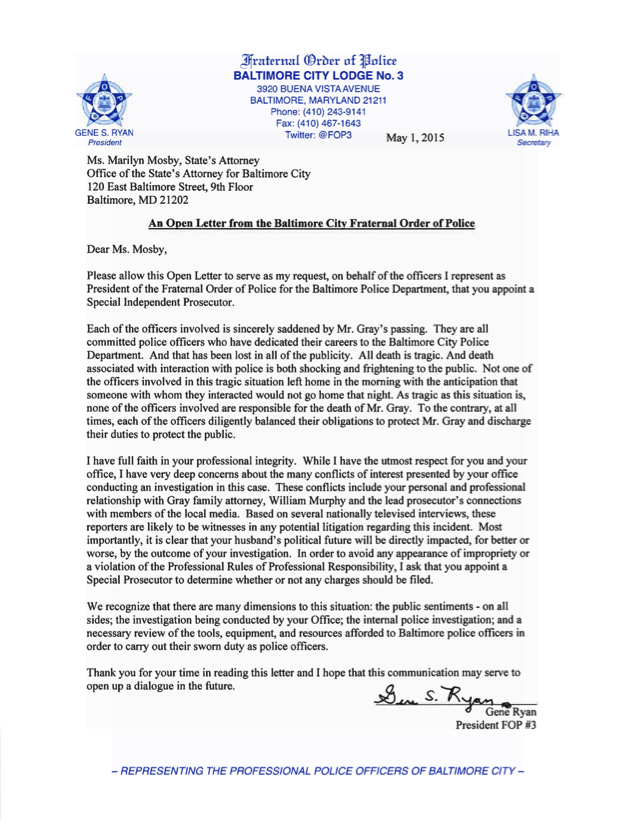

As many of you have probably heard by now, in the morning of May 1, the recently elected state attorney Marilyn Mosby announced that the six police officers involved in Freddie Gray’s arrest and transport to the police station have been charged with second-degree murder and manslaughter. The announcement was completely unexpected, especially after rumors had been circulating in the previous days about police authorities sticking to the version that Freddie actually deliberately broke his own spinal chord while locked up in the police van. These charges constitute an important victory, despite the police union effort to revert the verdict by pointing to an alleged “conflict of interest” between the state attorney, Gray’s family and the local media (see picture below for the official statement).

The struggle is not over, though. While people are now being arrested for defying a needless curfew (there have been no clashes, only peaceful rallies, since the National Guard entered town), concrete steps are needed to turn this victory into systemic change.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/baltimore-riots-police-racism/