Demonstration in Notting Hill on August 9, 1970 against police harassment of Frank Critchlow’s Mangrove restaurant. Photo: The National Archives UK / Flickr

The life and legacy of Britain’s Black Panther Movement

- October 27, 2020

Race & Resistance

The British Panthers are rarely recognized for their central role in the history of Black radical resistance — it is time to set the record straight.

- Author

It has been for some time now that Black people have been caught up in complaining to police about police, complaining to magistrates about magistrates, complaining to judges about judges, and complaining to politicians about politicians.

We have become the own shapers of our destiny as from today.

These words were uttered by Darcus Howe on August 9, 1970 as he addressed an estimated crowd of 150 demonstrators outside the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. The Mangrove demonstration and the trial that followed became monumental events in British legal history. In his speech, Howe, a member of the British Black Panther Movement (BPM) accurately expressed the frustration of his generation of Black radicals.

Determined for change, the BPM channeled their anger into action and fought against the British establishment, becoming one of the most powerful anti-racist organizations of the time.

When reflecting on Black radical resistance, the BPM is often omitted from popular accounts of history. This erasure is particularly controversial when one considers the incredible achievements made by the Black Power activists in the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 70s. Through endless campaigning and strategic organizing, the British Panthers fought against police brutality, challenged the state and demonstrated the importance of community empowerment.

Black Liberation through Black Power

The formation of the BPM came in 1968 after Hyde Park rebel Obi Egbuna joined forces with fellow activists Eddie LeCointe and Peter Martin to create a British equivalent of the Black Panther Party in the United States. Egbuna, a Nigerian-born playwright, was a frequent Speakers’ Corner orator who used his fiery anti-racist speeches as a call to action for the Black community in Britain.

The British Panthers were conscious that as Commonwealth migrants they were in a different position to their American counterparts, so their organization had to suit this unique context. Many of them, having migrated from countries in the West Indies, Africa and Indian subcontinent, had witnessed and participated in anti-colonial movements in their countries of origin.

This led the BPM to take an explicitly internationalist political outlook as they were aware that British imperialism not only affected Black people in the metropolis, but also in the Empire and Commonwealth. Additionally, one of the most notable differences with the American Panthers was the absence of guns amongst the BPM.

Anti-racist activity, however, was not a new phenomenon in the UK as there had been many debates on race and imperialism in the preceding decades. Since the 1930s, London seemed to attract Black radical thinkers from Africa, America and the West Indies. Activists such as C.L.R. James and Amy Ashwood-Garvey had been instrumental in organizing anti-colonial campaigns in Britain and even participated in forums for Black liberation, such as the 1945 Pan-African Congress held in Manchester.

Organizations such as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), founded shortly after Martin Luther King’s 1964 visit to Britain, had been active in critiquing discriminatory legislation and lobbying government officials for anti-racist measures. CARD featured an array of seasoned activists such as Marion Glean, Selma James and Dipak Nandy. However, CARD’s organizational structure — with white allies assuming key positions — and its closeness with centers of power led to internal tensions, as the Black community increasingly favored grassroots Black Power organizing.

Publications were used to spread awareness of the cause throughout the black community, with the publication of the Black Panther Movement’s Publications like the Black People’s News Service were used to spread awareness of the cause throughout the black community. Credit: The National Archives UK / Flickr

By the mid-1960s, Black American radicals, such as Malcolm X, frequently crossed the Atlantic and urged Black Britons to intensify their anti-racist action, this led to the locus of resistance shifting from the theoretical Black intelligentsia to the grassroots.

One of the most memorable visits was by American civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael who used his 1967 speech at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress to call on Black Britons to take a more radical approach to anti-racist resistance. Black Liberation, as he argued, could only be achieved through Black Power.

It was in the aftermath of Carmichael’s visit that organizations including the Black Liberation Front, Racial Adjustment Action Society and the BPM were formed. Though these groups adopted Black Power ideology to varying degrees, they shared a determination to protect the black community by any means necessary.

Fighting racism with confidence and conviction

Due to their adoption of political Blackness — the belief that all non-white citizens could unite under the term “Black” — the British Panthers’ membership was ethnically varied. Whilst the BPM had significant numbers of Black West Indians and West Africans, there were also prominent South Asian activists such as H.O Nazareth, Mala Sen and Farrukh Dhondy.

The reconceptualization of the term “Black” provided a practical means of organizing against the simplistic way that racists viewed non-white migrants. It united all non-white migrants in their struggle against a common evil: racism. Additionally, these activists knew that in the eyes of many white Britons they were merely a social “other” and that there was little difference between how Asian or Afro-Caribbean communities were treated. Therefore, political blackness was an appropriate principle for the British context.

In 1968, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, a Trinidadian doctoral student, took over leadership of the BPM after Egbuna was arrested on conspiracy to murder a police officer. Under her leadership, the BPM operated through strict organizational codes which involved attending group meetings, going on regular demonstrations and, most importantly, completing assigned readings.

Books by intellectuals such as Marcus Garvey, C.L.R. James, and Walter Rodney were deemed essential reading because they could raise Black consciousness while teaching the Black community about how to best achieve liberation. As well as consuming this literature, BPM members, such as Dhondy, passed on knowledge through youth education classes where texts like E.P. Thompson’s The Making of The English Working Class were on the agenda. For the British Panthers, education was vital.

The BPM in the 1970s featured an array of activists who brought a distinct energy and radicalism to the group, many of them utilizing the skills they acquired from previous liberation movements. Trinidadian activist and broadcaster Darcus Howe became involved with the BPM after 1971. He brought with him experience gained from participation in similar Black liberation movements in the West Indies and America.

Other members such as photographer Neil Kenlock, writer Beverley Bryan and activist Olive Morris played vital roles within the movement, as they documented the group’s activities and took part in door-to-door canvassing. In a recent interview, Kenlock recalled the way that the BPM encouraged them to live boldly and fight racism with confidence and conviction, saying that “We did it for the community [and] we weren’t afraid of anybody.” Similarly, Bryan reflected on the “fearlessness” of the Panthers and their belief that what they were doing “could impact what was happening in Africa and that you could link with people in America and Jamaica.”

An example of the transnational links formed by the BPM was the demonstration organized on March 2, 1970 outside the American embassy, in support of American Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale, who was on trial for murder and conspiracy charges. The demonstration, which resulted in sixteen arrests, saw BPM members argue that Seale’s trial was part of a government-initiated plan to undermine Black Panther organizing in America. As argued [PDF] by Anne-Marie Angelo, the BBP “saw themselves not merely as allies of Seale but as the direct victims of American oppression.”

A jury of our peers

A significant moment in the organization’s history was the 1970 Mangrove Nine trial which saw nine activists, some from the BPM, charged for riot and affray during a demonstration in Notting Hill on August 9, against police harassment of Frank Critchlow’s Mangrove restaurant, a long-time hub for the West London Black community. On three occasions, the police had raided the restaurant supposedly searching for drugs, but none were ever found.

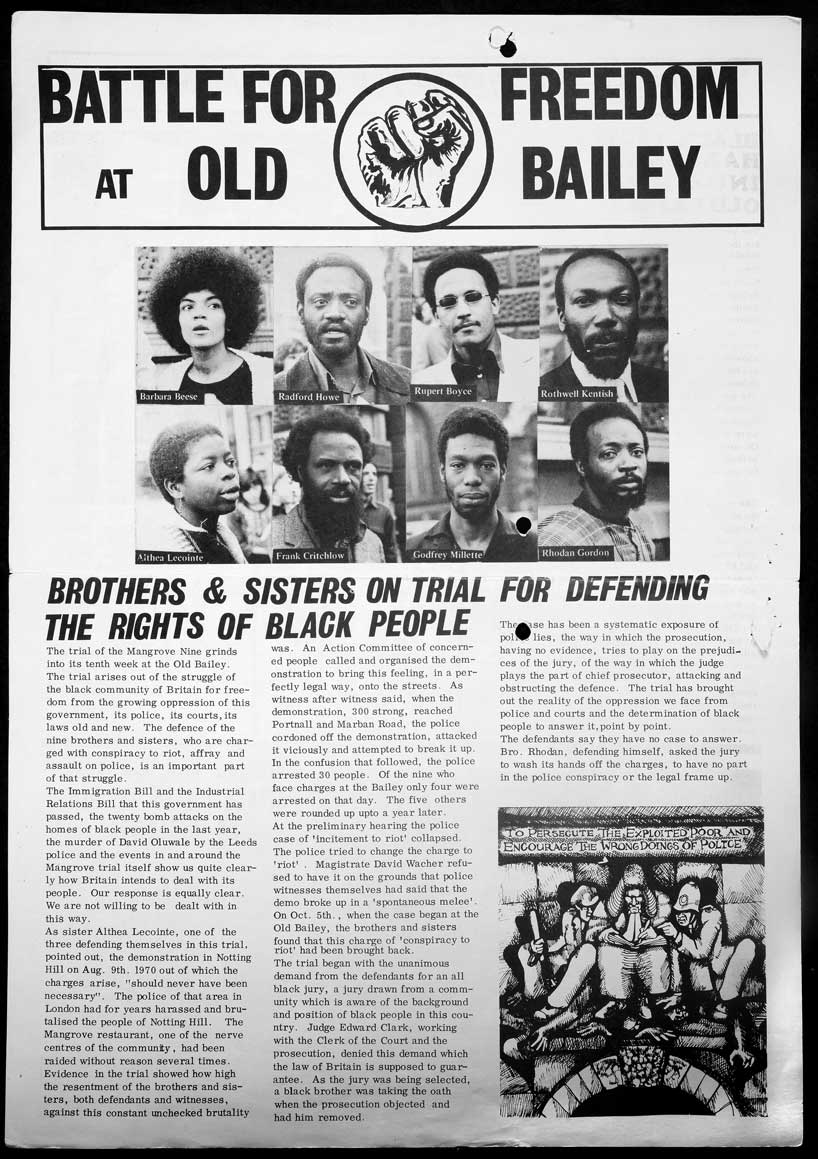

Flyer created in the 10th week of the trial that was distributed to Black people around the court and Notting Hill to raise public awareness. Credit: The National Archives UK/ Flickr

Critchlow’s well-known opposition to drugs within his restaurant and the systematic nature of the raids, led many to air their grievances at the demonstration, where protesters marched to three local police stations with Black Power placards. When the demonstrators reached Portnall road, violence exploded as they were met with hordes of police officers, which Howe described as being in “military formation.”

The nine individuals arrested during the march are thought to have been selected by the Director of Public Prosecutions due to their involvement in the demonstration and their prominence within the local Black community. The nine defendants were Althiea Jones-LeCointe, Anthony Innis, Darcus Howe, Barbara Beese, Rothwell Kentish, Frank Critchlow, Godfrey Millett, Rhodan Gordon, and Rupert Boyce.

During the trial, the Nine devised a radical defense strategy that would seek to communicate the Black experience and expose police racism. This strategy, orchestrated by defense lawyer Ian Macdonald QC, saw two of the Nine defend themselves and also saw the invocation of class struggle and colonial history as means of legal defense.

The 55-day Old Bailey trial began with Howe and Macdonald citing the Magna Carta in their application for an all-Black jury; despite the request being unsuccessful, it set the tone for the landmark trial. Defending themselves, Howe and Jones-LeCointe — later joined by Gordon — used their oratory skills to cross-examine the prosecution and display the structural racism that had long kept Black people oppressed.

The most successful technique adopted by the Nine was their decision to use an intersectional critique of race and class. The defendants, along with Macdonald, attacked the imperial structures of the courtroom and society-at-large. They demonstrated how the Judge’s position in the courtroom was used to intimidate the jury, how the court rituals reinforced class structure and how the rule of law had historically only favored the ruling classes.

In a 1972 documentary on the trial, Jones-LeCointe recounted how the “judge sit on high” thus enabling him to “keep [the jury and defendants] under control.” Explaining the significance of this, Macdonald stated that “The structure of the court is such that there is a tendency for that jury to identify with the judge.” The defendant’s task, as Macdonald explained, was “to make the jury go along with their working-class experience [and] their anti-authoritarian sentiments rather than to side with authority.”

The Nine’s success

During the trial, it was revealed that Special Branch operatives had been instructed to gather intelligence on the day of the march. These operatives were part of a Special Branch task force called the “Black Power Desk,” which sought to monitor and limit Black Power radicalism in Britain. Surveillance files on the British Black Power movement were first revealed by historians Robin Bunce and Paul Field in 2010. Since then, the Special Branch Project have archived and extensively researched the declassified documents.

Special Branch files on the Mangrove demonstration feature an array of photographs taken by the operatives. They also include in-depth briefings on the Nine defendants and their community activism. Jones-LeCointe and Howe were particularly singled out in the files as being leading figures and staunch advocates of Black Power. Such briefings reveal the anxiety of the state and the power of the activists to pose a real challenge to authority.

The majority-white jury, including only two Black men, ended up siding with the defendants, as the most serious charges of riot incitement were dropped. Judge Edward Clarke’s closing remarks signified the importance of the trial as it was the first time that racism within the Metropolitan police was acknowledged. Clarke’s unprecedented, yet cautious, statement noted that “regrettably,” the trial had “shown evidence of racial hatred on both sides.”

Protest in solidarity with the Mangrove Nine. Credit: The National Archives UK / Flickr

For the Black Power movement, the Mangrove Nine trial was monumental as it not only demonstrated Black Power in action but also articulated the Black experience in Britain. Clarke’s comments sent shock waves throughout the British State, as it caused great embarrassment for the police and the Home Office who had been closely monitoring the trial’s developments. As women’s rights activist Selma James recounted, “if the [Nine] had lost, they would have been in a lot of trouble with Police who would [have felt] empowered in what they were doing”.

Following the Nine’s success at the Old Bailey, Special Branch documents appear to show that the Black Power Desk was decommissioned as they had failed in their mission to stop Black Power activity in Britain. However, after the trial Black Power groups began to wane in influence and members due to organizational in-fighting and ideological differences.

The importance of collective action

By 1973, the BPM’s membership had dropped drastically and the organization underwent a rebrand, becoming the Black Workers Movement. Prominent members of the BPM such as Howe, Dhondy, Beese and Sen had left the BPM to run the radical Black journal Race Today with activists Leila Hassan Howe, Patricia Dick and Jean Ambrose. Similarly, female members of the Movement, such as Olive Morris, Liz Obi and Beverley Bryan left to form Black feminist organizations such as Brixton Black Women’s Group.

The BPM not only demonstrated the power of Black Power radicalism, but also the importance of collective action. Far from seeing themselves as helpless victims, the British Panthers fearlessly spoke out against racial injustice and remained in control of their own destiny.

Over half a century since the founding of the BPM, Black youths in Britain find themselves fighting the same battles of police violence and institutional racism. Whilst the global re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement has shown promising signs that our generation will fiercely defend the rights of the Black community, we must reflect on the history of our predecessors and learn from their mistakes and successes. A failure to engage with our Black radical past could severely derail our ongoing fight for liberation.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/black-panther-movement-uk/