#NoBorders solidarity banners in Berlin, May 2020. Photo: Amanda Priebe

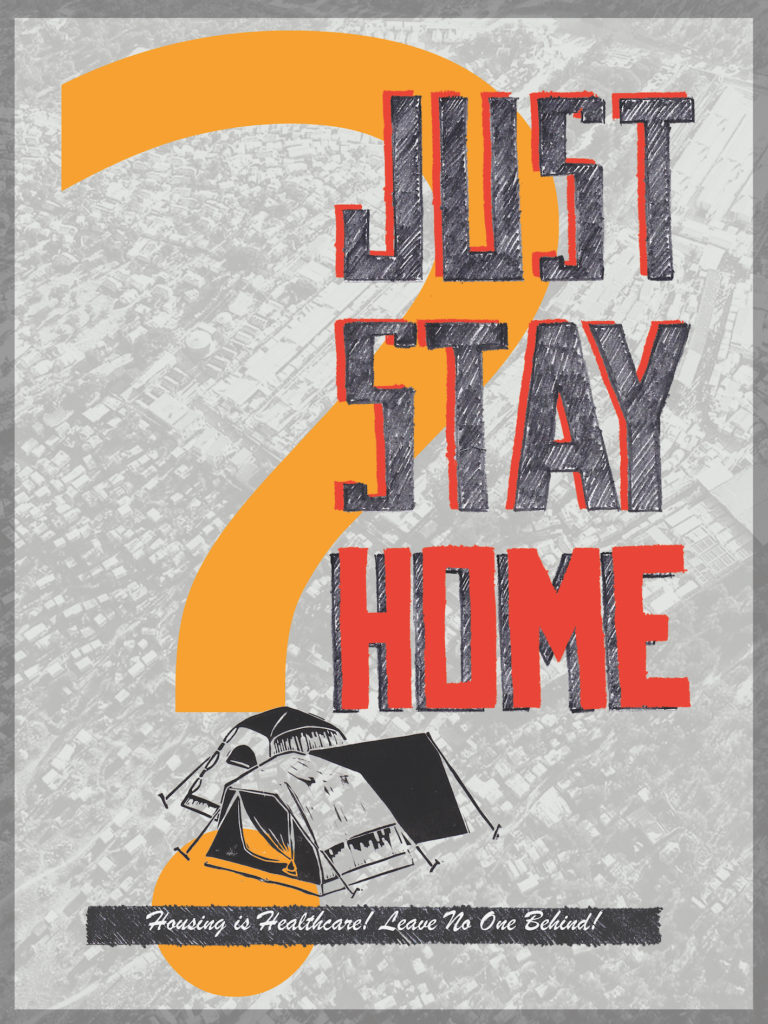

Towards a borderless world where we can all “just stay home”

- May 26, 2020

Borders & Beyond

Now may be a strange time to call for border abolition, but as the pandemic has shown: we are collectively no safer than the least protected among us.

- Author

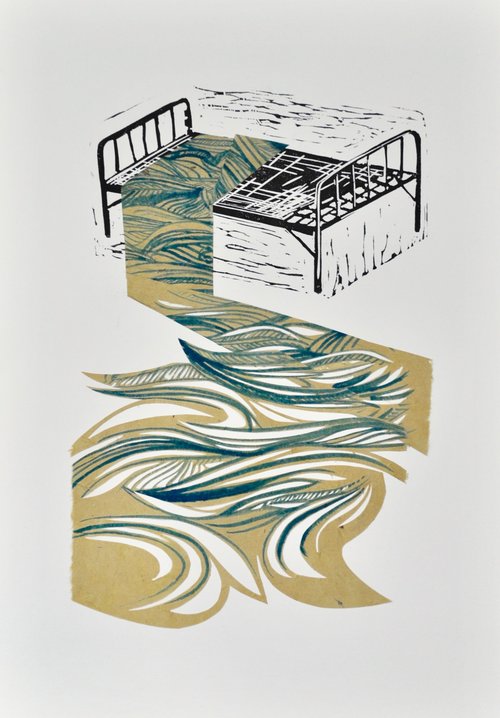

In Greek mythology, Procrustes was an iron smith and an innkeeper who offered hospitality to travelers on the road between Athens and Eleusis. Procrustes liked to brag to passing strangers that an iron bed in his inn had magical properties so that it would exactly fit whoever laid down upon it. However, the method of Procrustes’ “magic” bed was only revealed upon accepting his offer; to fit the traveler was either stretched or had his or her legs sawed off.

Pharmakon, linocut and ink collage on paper. Amanda Priebe, 2016

On the Greek island camps of fortress Europe, European “hospitality” likewise exacts its brutal price. Today, as COVID-19 has caused our worlds to appear to contract, the borders may seem as a distant and obscure abstraction. In this moment it is all the more crucial to understand the border not merely as a line on a map, but as an everyday practice reproducing inequality.

As the pandemic has made even more clearly visible the breathtakingly unequal foundations of our societies, so too has it uncovered the deadly reach of the border in our everyday lives.

It is at the borders — both at the edges of the nation state and at the edges of our imagination — where the vicious logics of containment and neoliberalism cause the most suffering and it is here where the radical struggle for “no return to normal” must begin.

Border abolition

Much has been written about the classed, racialized and gendered nature of who has the ability to “just stay home”. Poor, racialized and women workers are disproportionately represented in precarious and low wage industries now deemed essential. These workers are now forced to choose between risking their own health and feeding their families. Similarly, the expectation of home as a site of safe refuge is far removed from the realities of domestic violence, which has increased dramatically with lockdown measures across the world.

Incarcerated people, barred from social distancing and lacking appropriate sanitary measures, are some of the most affected by the virus and most at risk. Certainly, their families would love for them to “just stay home.”

For those who were born on the wrong side of the border, “Stay home!” is an all too familiar refrain. The threat of disease has long been used as a racist dog whistle to portray immigration as a public health menace. In the last two months, we have seen a doubling down on these kinds of narratives. There are well-documented links between anti-immigrant hate groups and the Trump White House, which has repeatedly labelled the coronavirus as a “Chinese virus.”

In fact, many of the border policies that Trump has sold as emergency responses to coronavirus were drafted long before the pandemic. Chief advisor Stephen Miller has argued for years that the president should invoke public health powers to close the borders. Border abolitionists understand that the supposed trade-off between economic security and public health is a false one. Such expansions of state powers that we are told are designed “to keep us safe” in fact target those who are already oppressed.

Now may seem to be a strange time to make the case for border abolition. In the midst of a pandemic, limiting non-essential travel to slow the spread of the virus is clearly necessary to protect those who are vulnerable in our communities. But the call for border abolition is more than a simple demand to immediately eliminate the security state; it is rather a call to build its replacement founded on ethics of care and mutual aid. As the pandemic has already viscerally illustrated, we are collectively no safer than the least protected among us.

The #StayHome border regime

The current regime of border walls and checkpoints is a dysfunctional modern obsession without historical precedent. Human beings have always migrated. The militarized and exclusionary border regimes in place today are thus not a timeless feature of human society, but rather an inheritance of 19th century nation states. Our collective memory in this regard seems especially short. Even the US-Mexico border had no wall until the 1990’s, despite being drawn in 1853.

The Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe argues that it is a contradiction of the classical liberal state to construe some movements as “freedom” and other movements as improper and threatening. In pre-colonial Africa, borders were permeable and “the most important vehicle for transformation and change was mobility.” The liberal state attempts to resolve this contradiction through a “managed mobility” that plays out along lines of class and race — but this arrangement is far from inevitable.

Despite the restrictions of COVID-19, the borders are still much less of an obstacle to those with the money and privilege to command their permeability. Travel bans have not impacted the ability of citizens to return to their countries of citizenship, regardless of possible exposure to highly affected areas. Privileged passport holders from the Global North for whom freedom of movement was never an issue continue to be the least affected by increased border restrictions. Yet they have played a prominent role in spreading the virus.

Just Stay Home? poster, linocut and digital. Amanda Priebe 2020

In March, Americans were able to cross into Mexico, taking advantage of lenient Mexican drug regulations to buy out stocks of the controversial drug chloroquine in border towns. These actions sparked protests by locals who feared that they would spread the virus in Mexico, a relatively unaffected country. In Europe, COVD-19 was spread overwhelmingly by people returning home from business meetings and vacations. In Brazil, where President Jair Bolsonaro has joined anti-lockdown demonstrations, the virus now devastating poor favelas was imported by wealthy Brazilians vacationing in Europe.

The world also remains a borderless playground for the movement of capital. In fact, as Justin Akers Chacon argues, in our neoliberal era “borders exist only for labor.” In Germany, talk of evacuating a small number of people from Moria, one of the most notorious Greek island refugee camps has stalled while politicians bicker over logistics. Moria now houses 20,000 people under horrific and unsanitary conditions in a space designed for 3,000.

Meanwhile, the German government had no problem hastily organizing a travel exemption for a “Spargel Brücke” (asparagus bridge) of low wage Romanian workers to pick this year’s asparagus crop. These low wage, precarious workers will not be eligible for German health benefits and will return to Romania potentially with both work injuries from strenuous labor and COVID-19.

A consistent view of borders as safeguards of public health would take into account that leisure travel for privileged passport holders plays a key role in spreading disease. Yet no one is suggesting limits on non-essential travel for Europeans once the pandemic is brought under control. In fact, “tourism corridors” are already being opened to EU citizens, while the rich remain free to move across borders to their doomsday shelters uninhibited.

For migrants and asylum seekers, whose journeys are essential travel, borders remain as dangerous and impenetrable as ever. Their crossings were always a question of life and death, not mere temporary inconvenience. Detention facilities have become even more horrific as deadly ticking time bombs where proper social distancing and hygiene measures are impossible. The practice of warehousing people in unsanitary and inhumane detention facilities is not only morally indefensible, it also poses a serious risk to public health. Detainees are at high risk of contracting the virus and spreading it further.

The Trump administration has already knowingly spread the virus through deportations to regions far less capable of dealing with a serious COVID-19 outbreak. On one deportation flight to Guatemala alone, 75 percent of the people tested positive for the virus.

If one does manage to evade the deadly oceans, deserts and detention centers and successfully enter the walled fortresses of the Global North, the border extends its reach, affecting everything from access to work and housing to education and healthcare. Undocumented workers or workers with precarious immigration statuses are less likely to have access to health insurance or seek out healthcare if they become ill due to fears of being deported. They are also more likely to work in low wage “essential” jobs, increasing their risk of exposure to the virus.

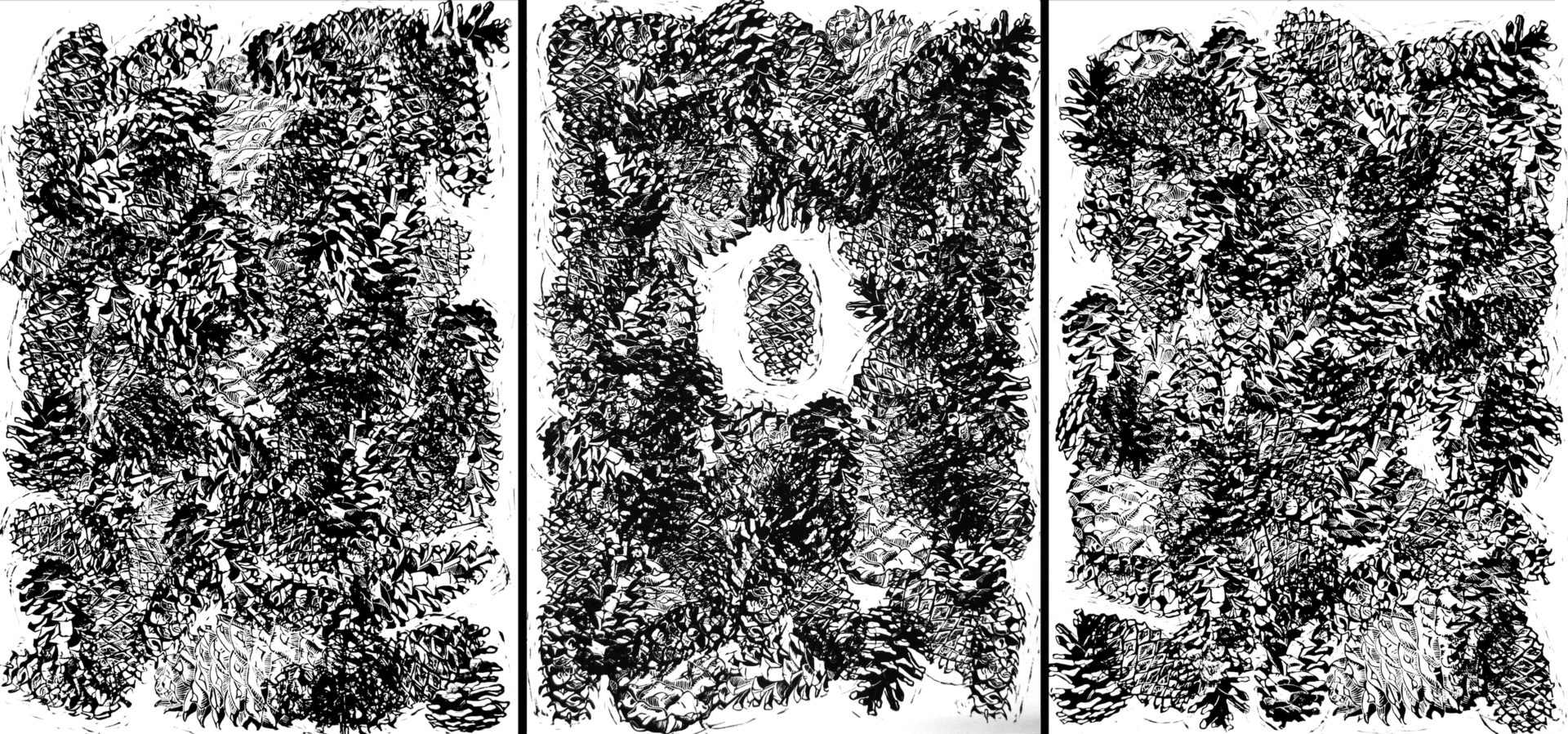

Proposal for a World on Fire, linocut. Amanda Priebe 2017

Safety without borders

Border abolitionists organize towards a society which meets the basic needs of all, regardless of citizenship status. An ethic of “no borders” demands that we not only address the current lethality of borders, but also that we create a long-term vision to look beyond national boundaries and conceive of economic and health security for all. In such a crisis as we now find ourselves, it would actually be possible for everyone to “just stay home.” Our politics are clear: no one is disposable; no one is left behind.

The no border-ethic thus must be understood not as a question of who has the right to travel, but of what responsibilities we have to each other. Today those responsibilities include social distancing and limiting our travel as much as possible. Tomorrow they may well include less flying and less leisure travel for those of us in the Global North. It means more focus on being good stewards of our local environment and building strong and interconnected communities.

Opposition to closed, militarized borders does not mean simply throwing open the gates, it means replacing the security state with structures and institutions built upon ethics of care and mutual aid.

If we are really concerned about public health during the COVID-19 pandemic, our concern and our solutions must take everyone into account — not only those people who already have somewhere safe to stay. There are many tactics we can use in pursuit of abolishing borders — from pushing policy decisions that provide immediate shelter and safety for migrants and asylum seekers to fighting for decolonization and participating in individual or collective direct actions that undermine border regimes.

Fundamentally though, our organizing must go beyond traditional debates of reform versus revolution to position “no borders!” as a frame for the revolutionary imagination and a practice of care against the destructive logic of containment. Practically, this means combining policy reform and direct action aimed at short term emergency relief, with the long term project of local organizing towards dual power and a truly borderless world.

As an artist, I am interested in how we can expand our social imagination of the possible.

One of the images I have come back to in my work is the pinecone as a symbol of abolitionist struggle. The lodgepole pine requires all of the destructive intensity of a forest fire to germinate; what appears at first as total destruction is actually the critical element of new growth and creation. This is how I think about the abolitionist struggle; not as destruction, but as creation. “No borders!” is not just a call for the elimination of the checkpoints and the razor wire and the detention camps, but for the founding of a society that could never build such things, knowing they are not what really keep us safe.

The COVID-19 pandemic is already shaping our collective imaginary — both potentially utopian and dystopian — of what radical new worlds might arrive in its wake. But the fight to wrench this moment from the grasp of disaster capitalism and refuse a return to business as usual is just beginning.

What comes next depends on the limits of our imagination and our capacity for organizing today. “No borders!” might sound like a utopian demand, but taking this principle seriously means we imagine a society that truly prioritizes care and safety for everyone — societies where we are all free to stay home because our homes are not in the midst of war zones, or the casualties of environmental destruction or epicenters of economic collapse — societies that prioritize stability and care for all those seeking refuge and safety.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/border-abolition-pandemic/