People impacted by human caging debt tell their stories. Photo: Debt Collective

The case for debt abolition: “We cannot afford not to rebel”

- September 21, 2020

Capitalism & Crisis

By turning individual indebtedness into a source of collective leverage, debtors’ unions can exercise material power and coordinate campaigns of resistance.

- Author

In 2008, around the same time Lehman Brothers collapsed and the mortgage market began to melt down, I got a call telling me my student loans were in default. I remember trying to grasp the logic as I spoke to the collector. Because I didn’t have money, they were increasing my principal by 19 percent. My balance ballooned, as did my monthly payments, which meant I was even more broke than before. My credit score tanked, further compounding my financial woes.

When I got involved in Occupy Wall Street a few years later, I realized my situation was hardly unique. Most people drawn to the encampments were also in the red. To talk to fellow protesters during the first few weeks of Occupy Wall Street was to talk about student loans that couldn’t be repaid, medical bills that were piling up, houses that had been foreclosed on by bailed-out banks, and insolvent communities forced to endure austerity measures, with people of color hit hardest. Millions were homeless and jobless, delaying starting families or losing hope of ever being able to retire, while bankers got massive bonuses. Perhaps organizing around indebtedness, some of us thought, would be worthwhile.

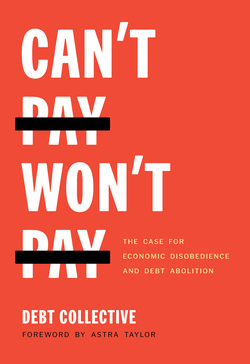

“Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay” by the Debt Collective is out now from Haymarket Books.

That’s what those of us who wrote this book have been working to do ever since. What follows is a jointly authored record of insights and ideas developed over years with various collaborators too numerous to name individually. Our efforts kicked off in April 2012 when the Occupy Student Debt Campaign (OSDC) organized a protest marking “$1 T Day” — the day outstanding student debt hit one trillion dollars — and demanding full debt cancellation and free public college. (The 1T protest was the first time I ever heard anyone make the call for student debt cancellation, and I was enrapt.) Over the coming months, OSDC merged forces with Strike Debt, a decentralized initiative focused primarily on public education. Strike Debt hosted debtors’ assemblies, where strangers gathered and shared personal stories and collaborated on a pamphlet called the Debt Resisters’ Operations Manual, which combined practical financial advice and a radical overview of our economic system.

A little over a year after Occupy began, we launched the Rolling Jubilee, a crowd-funded project that erased more than $30 million of medical, tuition, payday loan and criminal punishment debt belonging to thousands of strangers. We acted just like debt collectors, buying portfolios of debt on shadowy secondary debt markets for pennies on the dollar, but instead of collecting on them we erased them, sending people letters notifying them that their obligations were erased, no strings attached.

In 2014 we formally launched the Debt Collective, a union for debtors. Over the years we have developed a shared understanding of the central role debt plays in our economy and the way debt might be wielded as a form of power, an analysis we share in the following pages. Debt, we realized, bridges the individual and the structural, the personal and political, binding each of us to a broader set of financial and political circumstances — circumstances that have emerged over centuries of racist, colonialist and capitalist exploitation and wealth accumulation. Our goal has been to devise new creative ways to organize. Specifically, turning our individual indebtedness into a source of collective leverage in order to transform those broader conditions. As Marx famously said, the point isn’t just to interpret the world but to change it.

Taking inspiration from the labor movement, we believe debtors organized in a union can exercise material power over their common circumstances. The two modes of organizing have different targets but complementary aims. Where labor unions focus on sites of production, debtors’ unions focus on circulation, or how money and capital flow and to whom. Labor organizing targets the employer, demanding higher wages, benefits and more. Debtor organizing, on the other hand, targets the creditor (which, in the era of neoliberalism is also often the state). Debtor organizing fights against predatory financial contracts and for the universal provision of public goods, including healthcare, education, housing and retirement, so that people don’t have to go into debt to access them. These public goods and their access must be structured in ways that remedy long-standing and ongoing social inequalities.

The Debt Collective believes that it is not enough for public goods and social services to be universal, they must be reparative, too. One of the upsides to debtor organizing is that, unlike worker organizing, there have not been decades of class war aimed to suppress the tactic. Since the Labor Management Relations Act, typically known as Taft-Hartley, was passed in 1947, a lot of seemingly sensible union organizing strategies are simply illegal. The war on labor unions helps explain why only a small percentage of workers are organized on the job (about 6 percent in the private sector and 30 percent in the public sector). The core activities of organizing debtors have not been overtly regulated or restricted in the same way, leaving room to experiment. Debtor organizing has the potential to bring millions of people who may never have the option of joining a traditional labor union into the struggle for economic justice.

What follows is a document of collective thinking and an invitation to collective action. Like employers, creditors have enormous power over people’s lives. We are forced to debt-finance healthcare, education, housing and even our own incarceration. When we can’t pay, debtors are disciplined with steep penalties, high interest rates or loan denials and damaged credit scores, not to mention poverty, as unpayable bills come due. State power is often deployed to enforce unfair financial contracts through court judgments, garnishments and even jail time.

This book does not advise financial suicide but coordinated and strategic campaigns of resistance. An individual default is not a debt strike. As with any organizing campaign, there is no guarantee of success. Bosses retaliate against workers, and creditors can be expected to do the same to debtors who dare to throw down the gauntlet. But it is worth the risk, because the present is unbearable. Although many older people are also deeply indebted, the rising generation is the first in a century to face more dismal economic prospects than their parents, in part because they are being crushed by debt. In the United States, for example, student debt now surpasses $1.7 trillion. In better news, that’s $1.7 trillion of leverage to use in the fight for a different economic system.

If we don’t get organized, debtors will keep getting pushed deeper into a financial hole. In the throes of the pandemic, some payday lenders are charging close to 800 percent interest on short-term loans, taking advantage of people who have no other way to keep a roof over their heads or put food on the table. Mass unemployment in the absence of a functioning safety net intensifies mass indebtedness, fueling the already vastly unequal distribution of wealth along predictable racial lines. Meanwhile, financiers are becoming more powerful. When the stock market tanked, the Trump administration put the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock, in charge of a multitrillion-dollar federal fund tasked with buying up corporate debt. Meanwhile, the tens of millions of people who lost their jobs are expected to continue making monthly payments to banks and bill collectors.

We’ve entered unprecedented territory, but we’re not powerless. Over the last decade, once fringe left-wing ideas have become mainstream. Free higher education, universal health care, a Green New Deal, defunding and abolishing the police and debt cancellation are now popular policies, thanks to grassroots pressure. I’ll never forget how, back in 2012, 1T Day organizers were met with derision from the mainstream press when they called for student debt relief and free college. “They want all student debt in the country forgiven. All $1 trillion of it. And if the government would be so kind, they’d appreciate it if it would pay for higher education from here on out, as well,” Reuters’ Chadwick Matlin snarked. “What has happened to this proposal? Hardly anybody has cared.” NPR’s All Things Considered also covered the action, reporting that “most experts believe there’s little chance the government would ever forgive student loans.”

Those so-called experts were dead wrong. Over the last five years Debt Collective members succeeded in forcing the government to cancel more than a billion dollars’ worth of student loans and put student debt at the center of the 2020 presidential primary cycle.

The moral of the story is that we have to keep organizing. If we don’t, the crisis of indebtedness will only become more acute in the years to come. Personal debt has reached historic proportions, totaling $14 trillion, and staggering rates of unemployment and a decimated social safety net only raise the stakes. The chant that rang out at Occupy — “Banks got bailed out, we got sold out” — resonates in 2020, only it wasn’t just the banks that got a lifeline when COVID-19 crashed the economy. The cruise and hotel industries, the fossil fuel sector, meat packing plants, private equity firms and more all lined up to receive public money while regular people were hung out to dry. We need an organized, militant debtors’ movement now more than ever.

Given the way capitalism isolates and divides us, we have long needed to find a way to organize across physical distance and social difference and debtors’ unions offer one promising approach. Debtors who share common creditors are rarely confined to a single geographical location. Unlike workers, debtors don’t share a factory floor or office but are connected nevertheless, bound by the same creditors and an economic system that forces them into debt for basic needs. Coordinated campaigns of debt renegotiation and refusal can include people who live on opposite sides of the country, opposite ends of the city, or, in some cases, on the other side of the world.

I write this in the midst of intersecting crises. A public health crisis coupled with an economic crisis have intensified and exposed longstanding racial inequities, catalyzing a global movement against police brutality and white supremacy. With huge numbers of people newly out of work and vital social services being slashed, one thing is certain: many households, disproportionately households of color, will be forced to take on massive debts to survive the next year. Life was already difficult before COVID-19 crashed the economy; things are now becoming untenable. Racial capitalism is a centuries-long pandemic. We cannot afford not to rebel.

These days, the words crisis and apocalyptic couldn’t be more apt. The first term comes from the Ancient Greek and means the turning point in an illness — death or recovery, two stark alternatives. The root of apocalypse means to reveal or uncover. This is the truth unveiled by this apocalyptic moment: to truly cure ourselves and survive this crisis we are going to need way more than a vaccine.

We will also need more than debt write-downs or even debt abolition to heal what ails us, though that would be a welcome start. We need to completely transform our economy and society so that millions of people don’t have to live in perpetual financial and physical peril. We offer our thinking, research and proposals as a resource for everyone struggling to build a better world.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/cant-pay-wont-pay-excerpt/

Further reading

Orcas are not taking nature’s revenge, but we should

- Max Haiven

- September 24, 2020

Europe’s necropolitics sparked the fire at Moria camp

- Daniel Loick

- September 19, 2020