Protesters in Hong Kong. February 2020. Photo: YT HUI / Shutterstock.com

“Full Spectrum Resistance”: a field manual for insurgencies

- June 25, 2020

People & Protest

Aric McBay’s two-volume handbook for political action helps us to strategize, plan and organize effectively in order to achieve our goals of radical social change.

- Author

Looking back on the events of May and June, one might be tempted to think that nobody needs a field manual for insurgency — that rebellions just arise when conditions are ripe and victories inevitably follow, as spring follows winter.

Alternately, one might look at the same events — the uprising against police violence that began in Minneapolis and quickly spread throughout the United States and beyond — and see a series of missed opportunities, strategic blunders, tactical errors and political miscalculations, resulting in a range of symbolic gestures, temporary concessions and ineffective reforms, all far short of the ultimate aims of abolishing the police.

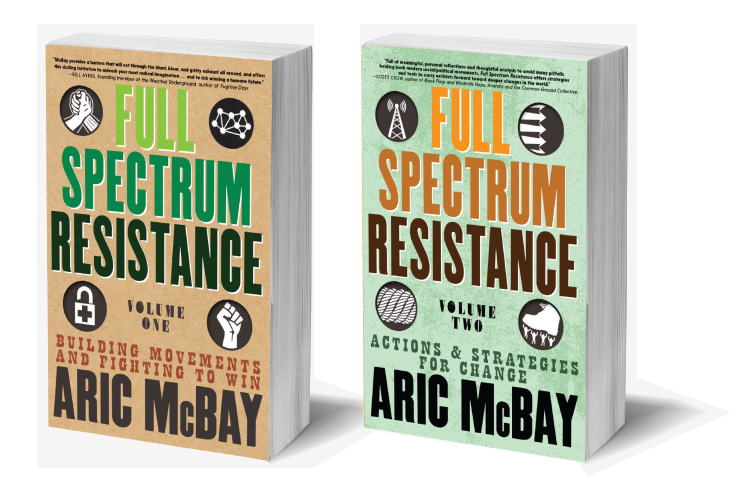

In that case, one might conclude that a field manual is exactly what we need. Luckily, there is such a thing: Full Spectrum Resistance, Aric McBay’s massive, two-volume, handbook for political action, covers the fundamentals of social change, offering advice on organization, strategy, tactics, security, communication (internal and external), and so on — all illustrated with historical case studies.

“Full Spectrum Resistance” (Seven Stories Press, 2019) by Aric McBay

McBay does not tell us what we should do. Instead he helps us learn to think about what we should do, and answer the question for ourselves in light of our actual objectives and circumstances. This is by far the stronger approach, especially because one thing that holds our movements back is the failure to think carefully and creatively about what we are doing, to reexamine our theories and alter course as needed.

Instead, we tend to engage in the same sort of actions as we always have, as if they were rituals, or reenactments. Peaceniks march against military interventions; workers picket job sites; antifascists “deplatform” right-wing speakers.

It rarely occurs to anyone to ask whether those tactics are well-suited to the goals of those movements, or to consider whether the goals are the right ones. The various parts of the left just acquire their own distinctive styles of action, modes of organizing, points of dogma and rhetorics — and then cling to them out of some combination of faith and dull habit.

Guerrillas and accountants

McBay wants to shake us out of our ruts. “We are losing,” he writes in the very first line of the very first page; it is time to try something else. He thus urges us to learn, not simply new tactics or talking points, but how to think strategically, and how to build organizations and movements that can implement our chosen strategy, and then learn and adapt.

The resulting manual — encyclopedic in scope and dense with information — is not the work of a singular genius. That, too, is a strength. McBay compiles and distills the lessons from generations of social movement organizing and its related scholarship. He draws from the environmental, labor, anti-war, civil rights, gay rights and feminist movements, as well as various struggles against colonialism and other forms of foreign occupation, and from organizations as different as the French Maquis, ACT UP and Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty.

The discussion of “Dynamic or Situated Hierarchies,” for instance, only occupies a couple of pages, but it looks to groups as varied as the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, the Deacons for Defense and Justice, historical pirates, the Durruti Column and the Kurdish YPG and YPJ.

From the plethora of specific case studies, McBay manages to draw lessons with a general applicability. However, the breadth of his approach and the willingness to learn from mistakes and defeats as well as successes, means that there is plenty here to challenge the conventional wisdom of whatever tendency you might identify with, from progressive moderates to Gandhian pacifists to insurrectionary anarchists to Black nationalists.

On the whole McBay’s advice is well-considered, sober, free from posturing and dogma, and in short, serious. It often serves as a much-needed reminder of what ought to be elementary common sense. He writes, for example, “Many tactical disagreements could be smoothed out if radicals at an action or in a campaign joined together as a bloc, organized and showed up early, explained their actions simply and in advance, and tried to calm anyone who got scared or upset by more militant tactics.”

Such straightforward solutions raise the question of why this sort of thing does not happen more often. Why do we need to be told to behave like responsible, grown-up people? Why has such an approach become so exceptional that it is somewhat shocking to see it recommended in print?

Likewise, while McBay is clear on the need for militancy, he is equally clear that militancy is not enough. That is true, in the first place, because tactics are not enough. “A diversity of tactics is not a substitute for good strategy,” McBay writes, adding later, “Tactics can only be evaluated in the context of a good strategy.” Without strategy, tactics are little more than empty gestures. But even within a confrontational strategy, a movement’s work has to consist of a great deal besides street-fighting and occasional arson.

The very notion of a “diversity of tactics” (a favorite trope of black-bloc types) implies that there is also room in the movement for quieter, more cautious, less bellicose action.

In this sense, McBay really does want resistance to be full-spectrum, availing itself of a broad range of approaches, using all the skills and creativity that many and diverse people can bring to the struggle. He refuses, therefore, to artificially rule out underground activity or violence; he equally refuses to fetishize what are always a small part of larger social processes. “Militancy is essential for successful resistance,” he writes. “But to make gains, the victories won by militancy must be incorporated into enduring organizations and daily life.” The movement may need guerrilla fighters and saboteurs, but it will also need lawyers, medics, artists, accountants and childcare providers.

We have no choice but to resist

Not that I always agree with McBay’s advice. For example, I think he himself offers plenty of reasons to disregard his rule “Don’t tell other people to slow down.” His impulse is of course a good one: to avoid “paternalis[m],” “dilut[ing] . . . tactics,” and “thin excuses for inaction.” However, much of this book is devoted to explaining the importance of strategy, planning, preparation, organization and a lot of other considerations that in practice mean looking before leaping, thinking before acting, and in general slowing down to make sure our efforts are not wasted and the risks we take are not pointless or foolish. It seems to me fairly obvious that not all “slowing down” is the same, and that there are circumstances where it is the best possible advice.

There is a way in which such agreements or disagreements are almost secondary. McBay’s advice is always well-argued, based in experience — his own, or historical — and clearly presented. One may disagree, but even then, the disagreement has its effect: it forces you to stop and consider why you disagree, to examine your own thinking, to question, to reconsider. McBay therefore models exactly the type of analysis he is trying to instill, and thus he nearly compels the same sort of rigor in the reader.

There are the occasional thin spots. The discussion of co-optation is unfortunately weak, missing the key fact that co-optation is a process by which opposition groups, or leaders, are granted access to power, but only so long as they limit themselves to demands that fit within established parameters. McBay’s discussion too closely equates this phenomenon with that of strategic concessions, whereby the authorities give in on select demands in order to placate and demobilize the moderate elements in a movement.

The two tricks of power are related, but importantly different: One works chiefly by limiting the objectives of the movement; the other, by dividing its supporters.

Perhaps the greatest oversight in this book is that there is no real guidance as to how to use it. The material calls out for serious study, and if it is to have its intended effect on our movements, its lessons need to be absorbed not merely by individuals but by groups and even formal institutions.

The book deserves careful reading and discussion; and collectives, organizing committees and even whole organizations would profit from reading and talking about it together. However the sheer heft of the work — two volumes, twelve chapters, 650 pages — may make it impractical to think that every member will read it straight through, especially if they are also engaged in ongoing organizing.

On the one hand, each chapter can serve as a stand-alone treatment of its topic; on the other, throughout the book, McBay sustains and develops an analysis of how movements work and how they can be made to succeed. The earlier chapters may not be necessary for understanding the later chapters but they certainly inform them.

My advice, for those looking to use the book for their organizing, is to take one of two approaches. One approach would be to have a small committee read the entire book and develop a curriculum tailored to the needs of the specific organization or campaign, selecting short readings as needed. That curriculum could then guide study in the rest of the organization.

The second, more involved approach, would have one or two instructors read the entire work to help with overall context, and then have other members of the organization read single chapters and present the material for the rest of the group. That would distribute the labor, while still allowing everyone to achieve some familiarity with the whole of the material.

McBay is careful never to understate the challenges, even the dangers, facing oppositional movements. He also makes a realist’s case that we have no choice but to resist. Resistance does not guarantee our survival — as individuals, as communities, or as a species — but allowing power to follow its own logic unopposed practically ensures that exploitation and oppression will continue, sometimes at genocidal levels, and likely leading to human extinction.

To avoid that fate we need radical action and militant tactics. But we also need strategy, planning and organization. Full-Spectrum Resistance may help us to get started.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/full-spectrum-resistance-review/