Militia members on the attack on the Aragon front, summer 1936

An Italian anarchist’s memories of the Spanish Civil War

- March 29, 2019

Anarchism & Autonomy

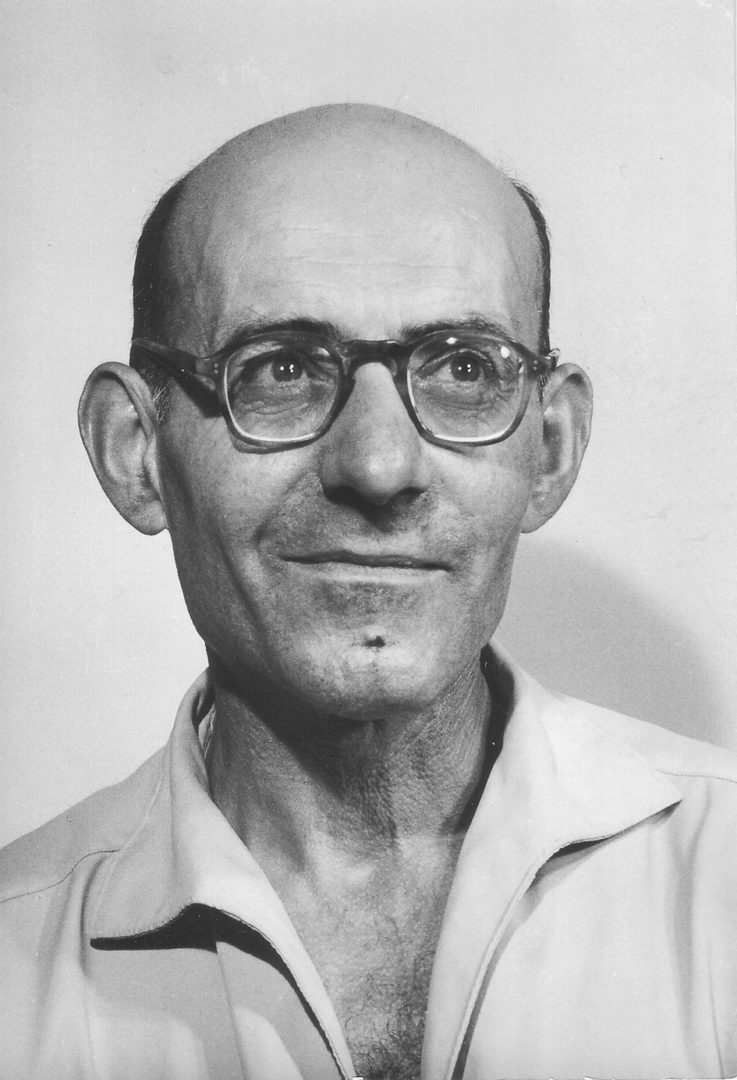

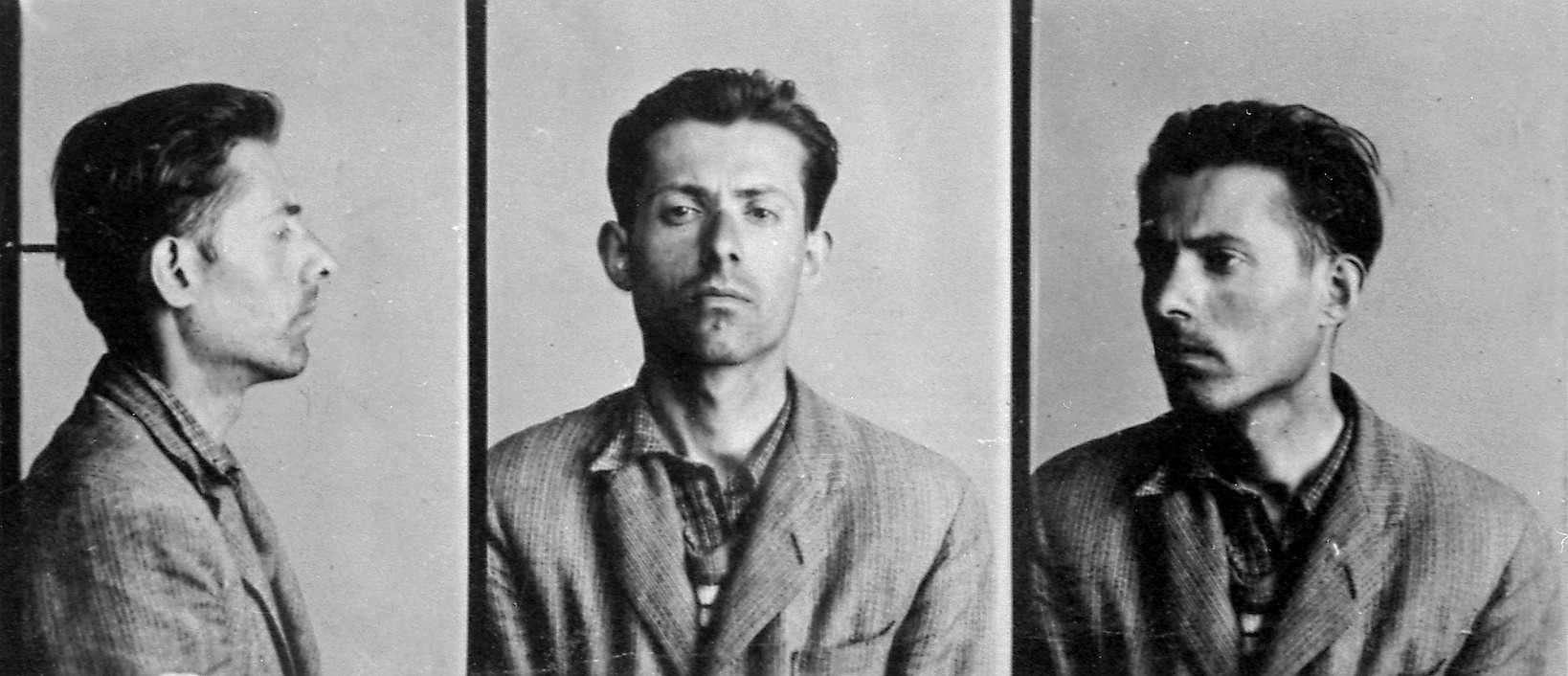

Antoine Gimenez was an Italian who fought in the Durruti Column during the Spanish Civil War. “Sons of Night” is the first English translation of his memoir.

- Author

In 1936 I was what is conventionally referred to nowadays as a ‘marginal’: someone living on the edge of society and of the penal code. I thought of myself as an anarchist. Actually, I was only a rebel. My militant activity was restricted to smuggling certain pamphlets printed in France and Belgium over the border without ever trying to find out how a new society could be built. My sole concern was living and tearing down the established structure. It was in Pina de Ebro and seeing the collective organized there and by listening to talks given by certain comrades, by chipping into my friends’ discussions, that my consciousness, hibernating since my departure from Italy, was reawakened.— Antoine Gimenez

Antoine Gimenez was born as Bruno Salvadori on December 14, 1910 in Chianni, Italy. Around the age of twelve he got into a fight with some fascist Blackshirts and was rescued by the Livorno anarchists. In fact, it was Errico Malatesta himself who visited young Antoine to make sure he was alright after having been knocked unconscious by the fascists. This was his first encounter with the anarchists whose libertarian ideas would continue to shape his thoughts and actions for the rest of his life.

His life as a chemineau-trimardeur (tramping artisan), as he would call himself, led him from Italy to Spain and France, where at one point, he was arrested and sentenced to jail for burglary and “carrying a prohibited weapon.” The next few years he spent in and out of jail, with the French authorities unsuccessfully trying to expel him from the country on several occasions.

In the mid-1930’s Gimenez ended up in Spain, where again he familiarized himself with the interior of the local prisons. In Barcelona’s Modelo Prison he started corresponding with Giuseppe Pasotti, a very active anarchist who would later take charge of the Political Investigations Service on behalf of the FAI. After his release from prison, Gimenez was deported to France, this time carrying a CNT membership card in the name of Antoine Gimenez — it was the definite goodbye to Bruno Salvadori.

Gimenez returned to Spain on the eve of the pronunciamento (the coup attempt by the fascists) and joined the Durruti Column, and later the column’s International Group. For the next few years he would be fighting on the front lines of the Spanish civil war.

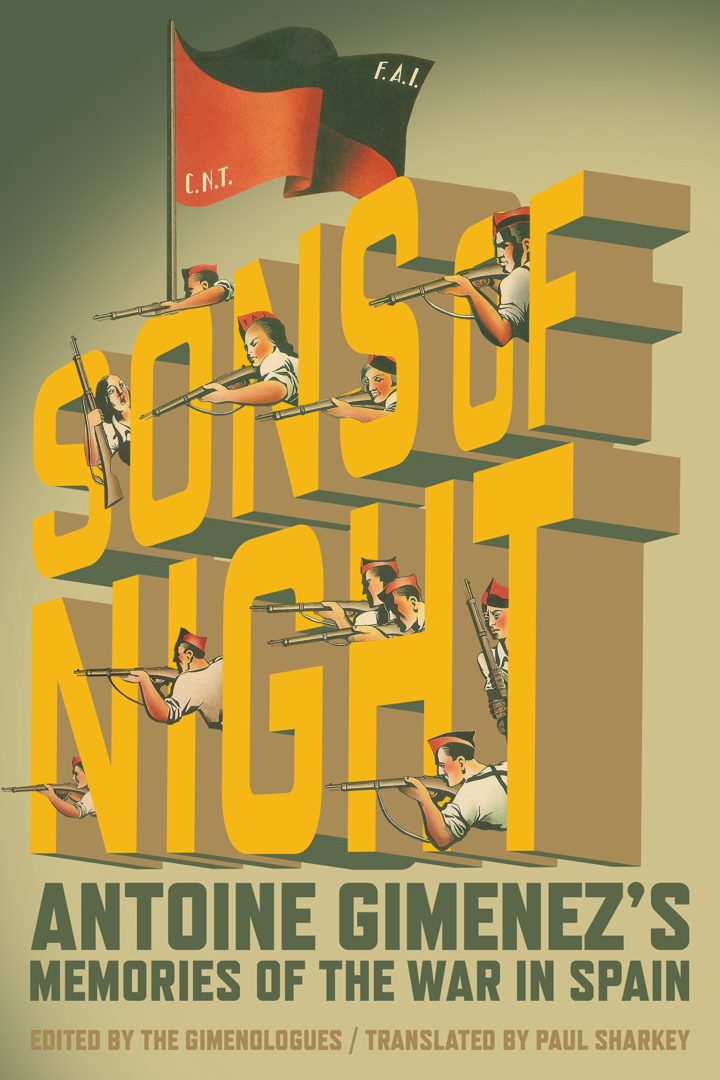

Sons of Night (AK Press, 2019) is the first English translation of Antoine Gimenez’ memoir, reconstructed and validated by The Giménologues, a group of friends who became historians over the twelve-year adventure of publishing Gimenez’s memoir. What follows is an excerpt from the memoir, and through Gimenez’ description of life at the front we can catch a glimpse of the unraveling of the libertarian revolution, both on the battlefield and in the rearguard, especially as the state imposed strict militarization upon the people’s army that had formed after the fascist coup attempt.

SARIÑENA

Typical of military logic, after telling us to move ten kilometers north of Siétamo, I was ordered to take a truckload of arms and munitions south. We were to head for Farlete on roads that followed the Sierra de Alcubierre, doing what we could to avoid the towns and villages occupied by POUM or PSUC units, which might have commandeered our truck.

Our newest recruit, Aznar, was at the wheel and telling me about life under siege and — for the tenth time — describing how, for ten days, their ears had been cocked for the slightest sound in the night; how, convinced that we were trying to starve them out, they’d relaxed; and how, once the patrols had passed by, they used to play cards, which is how I managed to get across. After opening fire at Affinenghi, they were convinced that, as had been the case on previous nights, we’d turn in for the night, taking our wounded comrade with us.

A few kilometers south of Siétamo we were intercepted by a group of irregulars who forced us to leave the passable trails and head cross country. The two comrades in the back were wounded during the shooting. Thanks to their courage and Aznar’s cool head we managed to shake off our attackers, but in the course of escaping we got lost. Unfamiliar with the area, we were obliged to drive on pretty much blind, heading southeast.

A steeple loomed on the horizon just as the engine started to fail, and Aznar started cursing like a sailor: “Me cago en Dios y en su puta madre, hijos de putas de todos los santos!” The truck came to a halt; we’d run out of gas. Aznar and the two wounded comrades — whose wounds were slight — asked me to go and find help. According to them, I was the best marcher. Aznar had to stay behind to booby-trap the truck and blow it up if necessary.

It took me an hour to reach Sariñena, a little fiefdom of the POUM. The POUM’s militias were organized in the class style of every army in the world; rank meant everything, and there was no arguing. At their HQ, I approached an orderly who referred me to the corporal, the corporal to his sergeant, and so on until I got to the captain who showed me into a large room, telling me I should wait there. The commanding officer was at a meeting, and the captain was not empowered to assign men with a car to bring out the required gasoline. My toothache was flaring again; it was as if needles were being hammered into my skull.

How long did I pace that room? I have no idea. I remember head-butting a door open and finding myself in a lecture room. A dozen people seated around a long table rose to their feet, startled by my intrusion. I shouted to them that I needed gas to get the truck rolling again and that I wanted to talk to whomever was in command there. They gathered around me, asking me who I was and where I’d come from. As if by magic, my toothache eased up. Orders were barked. I jumped onto a motorcycle, and the rider took off cross country, followed by a tiny car laden with gas cans.

By evening we were billeted in Sariñena, and I had lost my first molar. Our victory in Siétamo was nothing when it came to the progress of the war. The news was not good; Durruti had set off for Madrid, which was besieged by Franco’s divisions. Franco had taken over following the deaths of Generals Mola and Sanjurjo. In Seville, Queipo de Llano was supervising the push against Málaga. Up in the North (Asturias and the Basque Country), the fighting was still going strong.

In Pina, I’d finally admit to myself that “Gori” had been murdered by the communists in Madrid, outside the University City. I had already been told about his death, but I had refused to believe it, because ever since I’d met him, I had thought he was a dead man time and again. This time, though, the news was true. The communists hadn’t messed up. Manzana had replaced him at the head of the column, which they were beginning to refer to as a “division” — just the way our centurias had been turned into “companies.” During the early weeks, we tramped the Aragon front from the Sierra de Alcubierre to Velilla de Ebro. Reconnaissance patrols and raids alternated with stays in Pina, where I had reoccupied my digs at Tía Pascuala’s. She always delighted to welcome me in like the prodigal son every time I returned.

Madeleine was back from Barcelona. Her partner was still in hospital, making a slow recovery from his wounds. She used me as a sounding-board and would tell me that her countrymen didn’t know how to satisfy her. Unfortunately for her, in Pina, I slept at La Madre’s and she was billeted with a different family, and it was almost impossible for us to snatch enough time together to satisfy her. So she got back at me by not giving me any space the whole time I was in there. No matter where I went, she followed me around. I was often with Tarzan and Madeleine, and we looked like a couple out walking the family dog.

The news she brought back from the Catalan capital was depressing. The power struggle between the various factions in the republican camp was continuing. The CNT was now part of the government through García Oliver and Federica Montseny. Such partnership with the government, even if it was described as a coalition, amounted to treachery in my eyes and was proof that we hadn’t been clear-sighted enough to know that we shouldn’t be embracing the leadership style of the political parties and sitting at their table. But while doing our bit for the war effort, we had to retain our independence in social terms so that we could reject any law or systemic reform that might have flown in the face of the basic freedoms of the producer masses.

The reorganization of the column into battalions, companies, et cetera, was continuing. Gritting their teeth, the comrades were agreeing to be led by officers who were nearly always chosen by the troops or the union. These changes were most poorly received inside the International Group, so much so that a team of militants was sent down from Barcelona to persuade them to embrace the new arrangements, at least outwardly and on paper. María Ascaso was one member of that team. She dropped in to see me in Velilla de Ebro to give me a pack of French cigarettes and to take me to task for not coming to the meeting held at divisional CP, a meeting designed to persuade us to at least go through the motions of bowing to the demands of the restructuring of the republican armed forces.

We spent an entire afternoon arguing. She tried to convince me of the need for us to reassure the democracies, such as France and England, by making them believe that we were standing up for the Republic and had a strong, disciplined army ready to defend society as it stood on its territory. I tried to get her to understand that we were a group of irregulars with arrangements of our own and that we could be more effective by remaining outside of the army. I managed to convince her that I was right, but my success was short-lived. The majority of the group’s members caved in to suggestions from the propaganda team, which returned to Barcelona proud of having accomplished its mission. The only tangible result from militarization was that nearly all the Germans and a sizable number of the French and Italians left us in order to swell the ranks of the [International] Brigades in Albacete.

Durruti’s murder had seriously shaken any appetite I might have had for the fight. My friends Scolari, Giua, Otto, Mario, and Ritter belonged, with me, to a small band unfriendly toward militarization and the discipline that it entailed. Pablo knew that he could rely on us when it came to the crunch as long as he didn’t ask us to do things that we had always refused to do — even though they might cost us our freedom or material well-being. We were nearly all draft-dodgers or deserters. The exodus of comrades toward the International Brigades had cost us half of our strength. Pablo decided to send me to Barcelona to recruit more Italians and French and others from the Catalan capital, volunteers to swell our ranks; Giua, Ritter, and Otto came with me.

Sons of Night: Antoine Gimenez’s Memoirs of the War in Spain is now available from AK Press

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/gimenez-sons-of-night-excerpt/