Ponzi property: the neoliberal delusion of homeownership

- March 22, 2015

Capitalism & Crisis

The dream of homeownership has led many in the US and UK to buy into a Ponzi scheme of epic proportions. How much longer can the scam be maintained?

- Author

Despite the brief awakening offered by the Occupy movement, there really has been very little discontent with how our rulers have dealt with the aftermath of the global financial crisis in places like the US, UK and Canada. As the so-called neoliberal heartland, we might expect that people in these countries would go through the harshest of soul-searching following the collapse of our much-vaunted, although entirely delusional, free-market system.

Grumbling and carping aside, people have not taken to the streets, unlike in Spain or Greece, nor have people really mobilized to protest the mass looting of our taxes by the banks and other financial institutions. Maybe we got panicked into consenting to whatever our political and corporate overlords thought best for our futures. I think the reason is very close to home — pun very much intended.

It basically has to do with the pacifying effects of homeownership. Most people in the neoliberal heartland — and beyond — are deeply invested in the present financial order, at a personal and often visceral level. Since the 1970s we have become increasingly financially dependent, to a worrying extent, on the combination of rising homeownership and, more importantly, rising house prices.

On the one hand, homeownership rates in the US, UK and Canada had been rising for most of the twentieth century, but reached almost 70 percent as the financial markets started to collapse in 2007-’08. Even today, this rate remains around or above 65 percent in these countries, despite the shake-out — or should that be shake-down — of sub-prime borrowers.

On the other hand, and during the same period, house prices rocketed, almost doubling since the 1990s, for example. So while homeownership rates rose modestly since the 1970s — if slightly more sharply in the UK — falling interest rates and rising house prices have meant that we have all splurged on borrowed money. All three countries have experienced a major rise in personal debt as a result.

Now, homeownership rates are similar or higher in countries like Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal — so what is the difference? These countries experienced larger house price bubbles than the US, UK and Canada, and, consequently, their populations lost far more wealth (i.e., housing equity) as a result of the crash. This has been compounded by subsequent rises in unemployment and crippling austerity policies. Ultimately people in these countries now have much less to lose by taking to the streets.

So a less palatable reason for our acquiescence in the neoliberal heartland is that for many people in the neoliberal heartland, especially of a certain generation (older, outright homeowners basically), the global financial crisis has had a limited impact in many ways. Anglo-American countries are still sitting pretty, at least somewhat, for now. However, for the next generation of workers and potential homeowners things are not so bright, and this represents a potential threat to the future of our moribund economic system. It’s a threat we can use if we so choose, as I’ll explain below.

Well before the global financial crisis revealed house prices as the soft underbelly of contemporary, finance-driven capitalism, housing had come to underpin our economic livelihoods and personal lifestyles. The rise of homeownership and house prices since the 1970s necessitated that most people buy into the ‘housing dream’, both economically and culturally.

Our own house: we are expected to want it. We are expected to get on the property ladder as soon as we can afford it. We are expected to mow our laws, mend our fences, and defend our property whatever the cost. And most people in Anglo-American societies do just that — as those 70 percent homeownership rates illustrate.

Economically, this dream has played out through deliberate political strategies by governments to promote homeownership as a way to pacify populations. David Harvey has argued that American suburbanization “altered the political landscape, as subsidized homeownership for the middle classes changed the focus of community action towards the defense of property values and individualized identities, turning the suburban vote towards conservative republicanism.”

Culturally, it has played out through the constant bombardment of our senses with various forms of housing porn — TV shows about selling houses, renovating them, moving between them, upsizing, downsizing, ad absurdum. Thankfully, these TV shows have since quietly slunk from our screens, although there is still evidence of their alluring power (see the image above).

Why is all of this a problem? While on the surface things may seem pretty, below it they are far uglier. Basically, homeownership both entrenches and hides a number of deep-seated and unyielding problems we face should we want to change our societies.

First, and perhaps most important, homeowners — and pretty much everyone else in society — have become increasingly dependent on continually rising house prices in order to maintain their living standards. Real wages, by which I mean wages adjusted for inflation, have stagnated for most people since the 1970s in countries like the US, UK and Canada. Moreover, the austerity aftermath of the global financial crisis has simply reinforced this trend with many people yet to return to pre-crisis earnings.

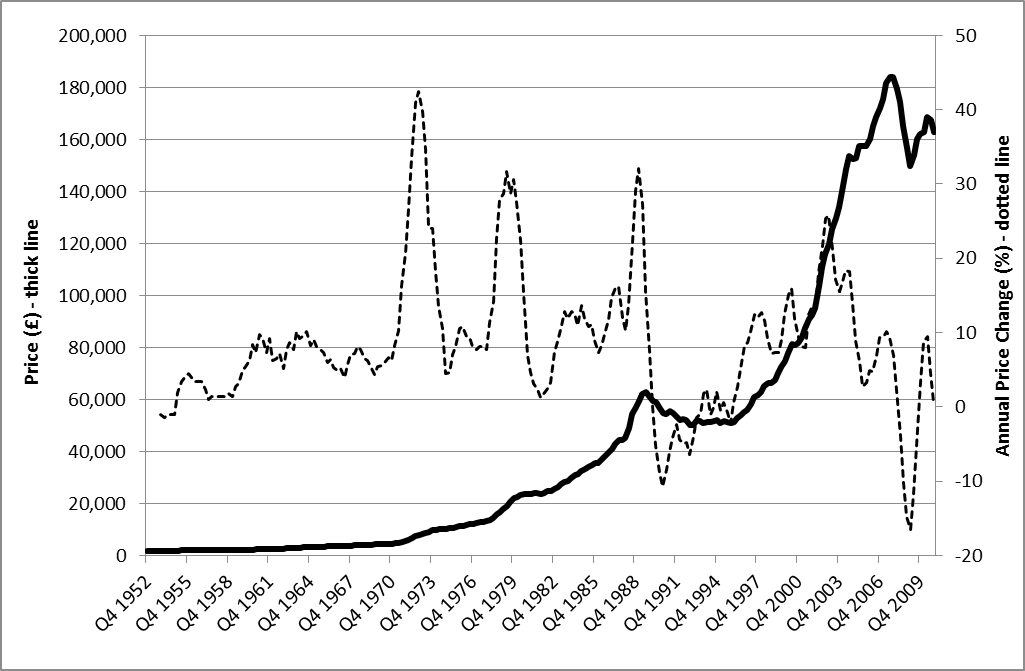

It is understandable that people put so much of their hope in rising house prices (see Graph 1), and so much effort in adding value to their homes (like renovations). Rising house prices have supplanted rising wages for many people, meaning that most people have become dependent on their house to finance things like their own lifestyles, their children’s education and future, medical bills, and so on.

Graph: Average UK House Price (left) and Average House Annual Price Change (right) (1952-2010). Source: reproduced from Birch, K. (2015) We Have Never Been Neoliberal, Zer0 Books; data on UK House Prices Since 1952 from Nationwide Building Society.

Second, and most perniciously, this dependence on housing and rising house prices breeds complicity with fiscal conservatism, encouraging and supporting the continuing stagnation of real wages, which the non-home-owning 30 percent of the population (the poorest) rely upon for their survival (as do many others).

Homeowners are turned into fiscal conservatives through their fear of rising wages, since such inflationary pressures might erode the value of their houses. As pernicious, corporate strategies to enroll sub-prime borrowers (again, the poorest in society) in the homeownership dream — or delusion — involved horrific forms of predatory lending, all of which has been well documented by the financial journalist Matt Taibbi.

While some people were rudely ejected from the home-owning dream, it’s not really surprising that the vast majority do not support any truly radical break with the past. Many remain bound, clinging desperately to the same imperative as before: ever-rising house prices. As a result, inequality is increasingly entrenched across the generations, with parents jockeying with one another to buy housing in the best school districts, lending their kids money for down payments, and so on. Attempts to break this cycle and create greater equity are treated to screaming, braying headlines in right-wing newspapers like The Daily Mail. Meanwhile government-imposed austerity policies reinforce this generational divide as the youngest are hit hardest.

Finally, the expansion of homeownership created an enormous economic boom in a number of countries around the world, most of which experienced a (brief or otherwise) hiccup as the global markets came crashing down in 2007-’08. Since then, it is particularly noticeable that house prices in the epicenters of greed like New York, London and Toronto have shot up again — and look like they won’t be coming down any time soon. Even that stalwart mouthpiece of free market capitalism, The Economist, has called London “The bubble that never burst.”

Continuously rising house prices, on which we all now depend, are themselves dependent on either selling off our housing stock to overseas investors — already happening — and the creation of “generation rent,” or enticing young, first-time buyers to put their hopes and dreams in the same Ponzi scheme as their parents. And I’m not calling homeownership a Ponzi scheme as some sort metaphor; it’s the very reason why Alan Walks refers to contemporary capitalism as “Ponzi neoliberalism.”

Promises of ever-rising house prices are premised on always being able to enroll new buyers in the property market with the promise of ever-rising house prices, and then letting the cycle start again. Without this promise — just like any other Ponzi scheme — housing would collapse and quickly lose its luster. But, and it’s a big but, first-time buyers wanting to jump aboard the Ponzi train now face a twofold dilemma.

On the one hand, since house prices are still rising in cities like New York, London and Toronto — the great centers of work, basically — they (or you) have to move to increasingly isolated and ostracized suburbs. Parts of the UK, for example, are now off limits to most people as average house prices have rocketed to many times average salaries: 14.9 times in Oxford, 13.9 times in London, 12.7 times in Cambridge, 10.9 times in Brighton, and so on. On the other hand, however, since house prices remain stagnant in many other parts of these countries, it’s become incredibly difficult to find anyone willing to sell their property: there’s just too much risk of negative equity.

What I find particularly egregious about all this is that we are still supposed to buy into the ‘aspiration’ of homeownership — we are not even considered proper adults or citizens in many cases until we have a mortgage weighing us down. Almost everyone still assumes you will buy a house someday (if you can afford it, that is). It’s such an entrenched assumption that people rarely frame it as a suggestion — “you should buy” — but simply a statement of fact — “when will you buy.”

Even amongst (supposedly) leftist scholars and activists the assumption holds: no-one wants to miss out on the golden property ladder it seems, even if property is still theft. What this collective delusion hides is that our grandparents, parents, friends and families are actually desperate for us to join their Ponzi scheme, for without our own desperate scrabbling for somewhere — anywhere! — to call our own, the value of their houses starts to tremble, crumble, and then fall.

This brings me back to my point at the start: a significant proportion of the population have bought into the rise of neoliberalism, or whatever we want to call the transformation of our societies since the 1970s. Can this state of affairs continue? Likely not, especially without the significant and continuous personal indebtedness of future generations. Who can find a house at four times their salary nowadays? That means that new buyers have to go into far more debt than their parents, in order to get less in terms of quality and yet face more risk. Is this just a new, improved form of pacification staring down the barrel of a mortgage? What can we, or you, do about it?

Now represents an ideal time to turn your back on it all. You can just not agree to pay all that interest on a house; you can stop financing previous generations through your ballooning debt; you can stop pushing up the value of their homes and their living standards; you can stop buying into the delusion of homeownership. We live in a strange society when one of the most radical decisions you can make is not to buy a house, but maybe that’s precisely what’s needed. At least it’s a good start.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/home-ownership-ponzi-scheme/