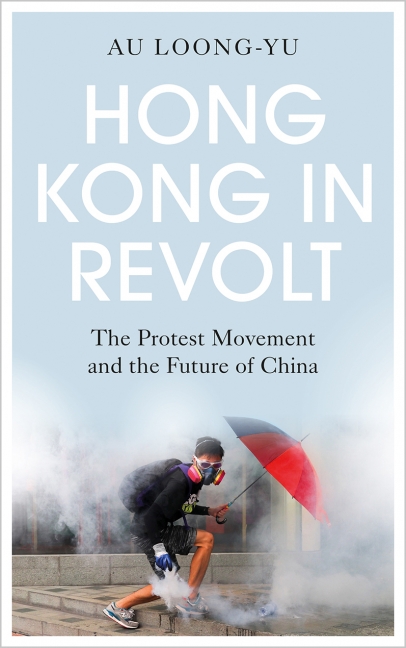

Protesters in Hong Kong, 20 October, 2019. Photo: Isaac Yeung / Shutterstock.com

Hong Kong in revolt: an interview with Au Loong-Yu

- September 28, 2020

People & Protest

To celebrate the publication of his new book, Au Loong-Yu joins us to talk about the origins, scope and legacy of last year’s Hong Kong rebellion.

- Author

When a group of protesters staged a sit-in at the government headquarters of Hong Kong in March 2019, little did they know that their actions would kick off the most significant wave of struggles in Hong Kong’s history. The sit-in was in opposition to the anticipated implementation of the “Fugitive Offenders amendment bill,” more commonly known as the Extradition Bill, that would give Beijing the power to extradite Hong Kong residents and visitors to the mainland. Protesters feared that by subjecting Hong Kong citizens to the mainland’s draconian legal system the bill would effectively end the post-colonial policy of “one country, two systems.”

As protests intensified, hundreds of thousands took to the streets. Global media became captivated by the protesters’ pitched battles with the police and their impressive array of new street tactics that have since inspired protesters around the world, from Chile to Rochester, New York. Even as the bill was rescinded and the media’s attention went elsewhere, protests continued, stopped only by the outbreak of COVID-19 at the start of the year.

In his new book, Hong Kong in Revolt: The Protest Movement and the Future of China (Pluto, 2020), labor campaigner and author Au Loong-Yu charts the origins of the movement, explores its internal dynamics and reflects on its significance for the future. To celebrate the book’s publication, ROAR associate editor Kai Heron interviewed Au about the protests and the future of struggles in China and Hong Kong, now wracked by the effects of COVID-19.

Kai Heron: As Mao’s old saying goes, a single spark can start a prairie fire. We hear often enough that China’s extradition bill was the spark that started the Hong Kong rebellion but as you make clear in your book, the rebellion’s causes run much deeper. Could you explain its historical context and why perhaps it was the Extradition Bill that ultimately lit the fire of rebellion?

Au Loong-Yu: It was the Extradition Bill that served as the spark for last year’s revolt mainly because it simultaneously involved not just two — Hong Kong and Beijing — but three parties: Hong Kong, Beijing and the “international community.” This combination shook Hong Kong to its foundations.

The first party, the Hong Kong people, had been conformant for many decades. They did not even protest, for instance, when London and Beijing negotiated Hong Kong’s future in the early 1980s without their consultation. But despite their passivity, Beijing did not feel secure, especially after its crackdown on the democratic movement in 1989 stirred up dissent.

In 2003, six years after the handover, Beijing tried to tighten its hold over Hong Kong by tabling the first National Security bill. When 500,000 people took to the streets to protest, the government was forced to backdown. On one level, this was not a major blow for Beijing since it had held onto a number of hyper-repressive laws that had been introduced under British colonialism — albeit now accompanied by a minimum of human rights protections — that effectively fulfilled a similar purpose as the proposed bill.

On another level, though, the 2003 legal offensive backfired for Beijing because it reminded Hong Kong that the mainland had not kept its promise to implement universal suffrage. Without this, it was clear that the Hong Kong people would remain powerless in the face of an Orwellian state. Since 2003 calls for universal suffrage have only become stronger.

The stage had been set for a full confrontation between the two sides.

The next flashpoint came in 2014. The Umbrella Movement, as it became known, demonstrated that the younger generation would not wait any longer. This prompted Beijing to take drastic measures in 2019 by tabling the Extradition Bill, which practically put an end to the separation of mainland China and Hong Kong in terms of their respective legal systems. Importantly, the bill made it possible for Hong Kong residents to be tried on the mainland under Chinese, rather than British, laws. Hence the great resistance against it.

At first, Beijing claimed that the bill was meant to extradite corrupt mainland Chinese who had fled to Hong Kong. But in truth, the bill’s purpose was to target anyone who happened to be in Hong Kong, including foreign visitors. This meant that the bill would affect Western countries, many of whom had interests in Hong Kong, with the US and UK at their head.

The bill therefore not only spelled the end of the policy “one country, two systems” but tore up the promise Beijing made to the West at the start of the negotiations between London and Beijing four decades ago. Both the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1985 and the Basic Law that came into effect in 1997 stipulate that Hong Kong would maintain its original British colonial laws — themselves based on British common law — for 50 years, implying that anyone in Hong Kong would be tried by colonial laws and Hong Kong judges, including a number of judges from Commonwealth countries.

This is far from ideal, but Beijing’s Extradition Bill was worse. It would put an end to the abovementioned legal arrangements and meant that anyone in Hong Kong could be tried under Chinese laws. Under mounting domestic and international pressure, the bill was rescinded by the Hong Kong government, only to be reincarnated in the form of the July 2020 National Security law, imposed from Beijing.

Until recently both the US and UK had been accommodating towards Beijing, even after the latter’s crackdown on the 1989 democratic movement. The arrangement had brought huge economic benefits to both sides. In 2015 when the Hong Kong pan-democrats, under pressure from the previous year’s Umbrella movement, wanted to veto the government’s reform package that would grant universal suffrage but deny Hong Kong people the right to nominate candidates for the head of administration, representatives from the UK and US establishment lobbied the pan-democrats to accept the bill rather than vetoing it.

The position of the US and the UK in this regard could be understood by the fact that they had hugely benefited from Beijing’s “one country, two systems” policy in Hong Kong. The 1997 Basic Law not only protected their political, legal and cultural privileges, but it also boosted their economic interests because of Hong Kong’s role as the third largest financial center in the world.

The 2019 Extradition Bill threatened these arrangements. It is widely believed that the bill was written this way because Beijing saw targeting both Hong Kong people and foreigners as a necessary act of retaliation against the Canadian government’s arrest of Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei’s boss on an extradition request from the United States.

Whatever the reason for the bill, it moved the UK and the US to abruptly change their policy of engaging with Beijing towards a more confrontational stance that would support the Hong Kong people’s opposition against the bill. Without the intervention of these “localized foreign forces” the local revolt alone would not have created such huge repercussions.

Coverage of the rebellion in Western media suggests that the protests have widespread popular support. Predictably, what is missing from this narrative is how class and social status shapes participation in the protests. So what is the class and political composition of the movement? Is it a mostly young movement? And what explains this composition?

According to a 2020 report by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, among 26 major protests in 2019, the “middle class” accounted for between 42 and 65 percent of total participation while the figure for the “lower class” was between 28 and 40 percent and the participation of the “upper classes” was negligible. The limitation of this kind of self-described “class identity” is that it often reproduces misconceptions about class identity found among the general public.

In Hong Kong, “white collar workers” like teachers and nurses, for example, are considered “middle class”. But while they might be paid more than those in so-called “working class” jobs like cleaning, both “classes” are dependent on the wage-relation for their reproduction and both organize in unions. So it is safe to say that when students are factored out, protest participants were mainly workers in a broad sense.

What is interesting about the revolt is that it started as a broad, popular, movement. In June 2019, two months after the first huge protests, the movement was powerful enough to demand and organize a general strike on August 5, where 350,000 employees stopped work and joined rallies across the whole of Hong Kong. This was the first successful and genuinely local political strike since 1949 and it paved the way for the birth of a new trade union movement with dozens of new trade unions formed by the end of 2019. This was the first time ever that labor organizations had such a visible role in the local democratic movement.

On top of this, there is also a section of the revolt’s participants whose class status is not yet entirely clear, namely, students and recent graduates. Nearly half of the participants to the three biggest protests numbering up to two million people were under the age of 30, and among them students or recent graduates accounted for around 30 percent. It is a generation that I refer to in my book as the “1997 generation”: those born just before or after 1997 when Hong Kong was handed over to China. Their presence was even more visible during smaller and more radical actions.

The perception of Beijing among the “1997 generation” is that it is nothing but an oppressor, not just in the sense of political rights, but also of their very identity. Since 1949 mainland China and Hong Kong have embarked on very different historical trajectories. Especially since the mid 1970s, when the British government, which was becoming increasingly concerned about an ever-stronger China, began to soften its authoritarian rule in Hong Kong. The more liberalized Hong Kong became, the more it differed itself from China. Along with economic prosperity came a growth in self-awareness, civil spirit and an increasing consciousness of the binary opposition of “a free Hong Kong versus an autocratic China.”

These changes gradually converged into a unique “Hong Kong identity,” although at its earlier stage it was still a very soft identity, one that was not necessarily excluding a “Chinese identity.” This only started to become stronger after Beijing began to attack Hong Kong people’s language rights by trying to replace Cantonese with Mandarin as the primary language for education more than a decade ago. Imposing its “national education” on Hong Kong students further alienated the young people. That was also the moment when the term “localism” became popular among them. Many of them now feel that in nurturing their home city and resisting encroachment from Beijing they have found some meaning in life other than making money. This new awareness was what empowered first the Umbrella movement, followed by last year’s revolt.

One of the fascinating questions you discuss in the book is how the movement interprets itself. For those living in the US and Europe in it can be hard to even ask this question. On the one hand there is an increasingly strong anti-China slant to our news that colors reportage of the movement. Mainland China is framed as an uncompromising aggressor while any potentially unsavory aspects of the movement are passed over in silence.

On the other hand, there are some left critics of the movement who see its calls for greater autonomy and democracy as a thinly veiled anti-communist call for liberal capitalism. They find evidence for this in images of protesters waving US flags or calling on Trump to help their cause. What do you think about these accounts, what other misperceptions have you noticed in the mainstream and the left, and how does your attention to how the movement makes sense of itself help to adjust the picture?

Judging from what Beijing has done to Hong Kong people since 1997, it is legitimate to say that the former is the latter’s direct oppressor. I also think that depicting last year’s revolt as anti-communist is blatantly wrong. The revolt produced a document containing its “five demands.” While four were related to the Extradition Bill and police violence, the last is about universal suffrage. I do not see any “anti-communist” element here. Because of its five demands, the revolt was surely “anti-Chinese Communist Party,” but that does not equate to “anti-communism” because the CCP today cannot represent communism or socialism — it is their antithesis.

Most parts of the world implemented universal suffrage a century ago, but not Hong Kong. Of course, Beijing is not alone in denying us this basic right — the UK did that for more than a century. This, however, only goes to show the tragedy of the Hong Kong people. Decades on, they still do not have a say over their own government or their own fate in general. This makes the case for universal suffrage more justified than ever.

I am not denying that there were real right-wing forces within the movement, but they were marginal and could not have led or shaped it. Actually, the two million-strong movement was largely spontaneous and had no recognized leaders at all. What unified the millions of people were the five demands, not the demand for independence, nor the support of Trump. Both Western media and pro-Beijing supporters loved focusing on people waving the US flag instead, albeit for quite opposite reasons. But this ignores the fact that most protesters did not wave it. A small minority of protesters were put under the limelight while people carrying the Catalonian flag or holding a pro-Catalonia rally, in defiance of the pro-US right wing, were ignored.

In addition to those conscious right-wing currents, there were also young people waving the US flag who did not belong to any political party. On the contrary, they were mostly new hands in the social movement. They might carry a US flag, or the Union Jack, or a Taiwan flag, but most of them did this to call for international support — they thought that waving a country’s flag could achieve this goal. One might say that these protesters were a bit naive — and they were — but it is important not to conclude from their actions that they are politically aligned with these countries.

A further problem with last year’s revolt was that most protesters had no idea of “left versus right.” Everything in the world was squeezed into their worldview of “either Beijing or us,” which led them to accept any foreigners’ help, without asking the question “are they your real friends?” On occasion, this lack of understanding allowed protesters to be played by the pro-Trump current, which was then magnified by the media.

So overall, and speaking from a from a broader historical point of view, I think it is helpful to see last year’s revolt as the gradual awakening of many Hong Kong people who had previously been apolitical. They learned fast, yes, but they were still not fully equipped. Under these circumstances, it is understandable that some acted unwisely. This does not mean that they cannot learn or that they cannot be brought over to an organized left. We should fight determined right-wing currents, but when it comes to the majority of this movement we should act like an open-minded teacher patiently showing new hands an alternative.

For those of us watching the protests from afar, the movement’s street-level organization and tactics have been a marvel to observe. How did this organization emerge, how has it endured, and what lessons, if any, do you think those outside of China can learn from them?

The interesting thing about this revolt is that it had hundreds of big and small protests but there was no broad organization behind them. For the big marches it was always the Civil Human Rights Front which applied for the license from the police, but its role ended there. Everyone, the Civil Human Rights Front included, was aware that it was not the political leadership of the protest and enjoyed no authority; this was why it often publicly stressed that it had no control at all over the protesters’ behavior. The participation of political parties was negligible.

Usually the eye-catching part of the marches was when the “braves” began to confront the police. These were the protesters on the front lines who would consciously and purposefully engage in clashes with the police. One would be impressed by the well-developed division of labor — throwing Molotov cocktails, building roadblocks, holding up the defense line to protect the “braves” from rubber bullets, transporting tools and materials, healing the wounded etc. There were also people who specialized in putting out campaign literature and cartoons and online and field “sentinels” to monitor police movements.

There were no overarching organizations that took care of this, only very small autonomous groups of usually no more than a dozen members. Each of them chose their own role. Therefore it was not rare to see too many first aiders running around while there were too few Molotov cocktails. The enthusiasm of the young people compensated for the lack of organization — with their motto “be water” in their heads they were ready to shift their role to make ends meet. Communication software such as Telegram and Instagram facilitated the exchanges of views and coordination among protesters. Hence the confrontation with police, while not 100 percent unorganized, was largely spontaneous.

“The braves” were inspired by the European Black Bloc, but they eventually surpassed it in terms of intensity and duration. One might say there were excesses as well, like the smashing of the subway and the torching of one pro-Beijing counter-protester who was seriously injured. Yet as a whole there is an important lesson here: in contrast to the Black Bloc, the Hong Kong “braves” did enjoy very broad support among the population. A survey showed that the revolt, characterized by fierce street fighting and vandalism, had an approval rate of 60-70 percent of the population.

This was in stark contrast with the very peaceful marches of the past 30 years. The popular slogan “It is you — the government — who showed us peaceful protest is useless” bore testimony to why the revolt carried broad support among the general population. The fact that the revolt was largely spontaneous speaks for one truth: it is the people who make history. This aspect of the rebellion echoed all the great revolutions of the past several centuries. It is a lesson that today’s generation should take to heart.

As you explain in your book, COVID-19 has given the Chinese Communist Party renewed license to intervene in the daily affairs of Hong Kong’s people. How has the pandemic changed the terrain of struggle in Hong Kong? What else has changed in the time since you finished the book and how will this play into the movement’s future?

With the outbreak and spread of COVID-19 in Wuhan in early 2020, Hong Kong people were immediately on the alert. They recalled how the SARS pandemic that first began in mainland China in 2003 had soon spread to the city, causing more than 700 deaths. So this time around, the newly founded Hospital Authority Employee Union — whose 20,000 members account for one-fourth of all Hospital Authority employees — called for a five-day strike to press the government to temporarily close the border to stop the virus spreading to Hong Kong. This aim was partially achieved two days later. The newly-founded union had proved its strength. In late March, the government had to further tighten the measure in the face of the worsening situation and general discontent among medical staff.

Soon, Hong Kong’s government realized that it would be a shame to let a good crisis go to waste. The need to impose lockdown and social distancing gave it a perfect excuse to curb protests. On many occasions, a hundred or more police offers hunted down just a few protesters. It also used the pandemic as an excuse to defer the legislature election for a year, which was bitterly opposed by the opposition. On top of this, Beijing had directly imposed its National Security law on Hong Kong on July 1. The combined result of all of the above attacks has been to effectively put a stop to protests altogether.

Recently, with strong encouragement from Beijing, Hong Kong’s government launched a city-wide check-up for COVID-19 to find silent virus carriers. The opposition is against this as they fear that Beijing may extract DNA from such tests so as to impose the Social Credit system — already in place in the mainland.

This system collects the information of citizens and then evaluates their “trustworthiness” and rewards or punishes them accordingly. The Hong Kong government stressed that the test was not related to the Social Credit system and that it would be voluntary. Soon it was reported that certain big corporations made their employees do the test. With the defeat of the people’s resistance last year, we have entered a new phase of reaction, and the pandemic has been weaponized by the government to ensure its victory.

What kinds of struggle do you think we can expect to see in Hong Kong and mainland China over the coming years and decades? Do you have any hope in these struggles taking a radical anti-capitalist direction? And if so, will this emerge in alliance with anti-capitalist members of the Chinese Communist Party or will a struggle have to be waged against the Party?

An anti-capitalist labor movement in mainland China is not probable in the short term, simply because the ruling class has already put in place complete control and repression to keep that from happening. In addition, the regime also completely restructured the old working class in the 1990s by privatizing state-owned enterprises, while firing 30 million workers. On the other hand, it also turned 250 million peasants into urban migrant workers. This also meant replacing an old working class, which had some kind of collectivist consciousness, with one that is more individualistic and one which, at least in the first period, had no idea of its own rights.

On top of this, in the 1990s, intellectuals for various reasons, failed to see the laboring class as their ally for democratic and socialist change. There was a heated debate between the liberals and the “new left.” While the former argued for “efficiency over equity” so as to legitimize their support for privatization, the latter argued for the reverse, which was to a certain extent an argument against privatization. Unfortunately, the “new left” mainly interpreted “equity” along economic and not political lines. That was why, despite the heterogeneity among themselves, the common point of the “new left” was that they saw the one-party dictatorship as the bearer of “socialism” and supported its status quo and opposed any idea of political liberties or free election. This led them to align with the state rather than with the working class. Only small groups of new leftists became involved in solidarity work with the latter.

The combination of the above three factors keep the working class as a class in itself but not — yet — for itself. Meanwhile, the absence of a labor movement has also sealed the fate of both the liberals and the “new left”; they were either crushed, co-opted, or simply disappeared. The monolithic party state is now all powerful.

At the same time, I also argue that the party state may be its own antithesis in the long run. Both the Soviet Union and the CCP became capitalist four decades ago, however unlike the former who had experienced tragic de-industrialization, Beijing’s turn to capitalism resulted in even more radical industrialization.

We now have the world’s most populous working class, numbering 350 million. Urbanization rates have since long surpassed 50 percent. China is no longer a poor peasant country. From this reborn working class, a voice for change will sooner or later be heard. In the past 20 years, through their spontaneous economic strikes, the workers are now more conscious of their rights, and steadily raising their expectations. This was also what was behind the constant rise in wages in the past decade.

If an anti-capitalist labor movement could ever break loose from state and party repression, this would be necessarily in opposition to the party state. I do not see there is any reason to assume that there is or will be a sizable genuine socialist democratic force among the middle and upper level of the party. Absolute power does corrupt people. Since the onset of “reform and opening,” besides facilitating the rebirth of the private sector, this first and foremost has helped the party officials to enrich themselves.

This is what people have called “bureaucratic capitalism,” something which I discussed in my 2012 book, China’s Rise: Strength and Fragility. Party officials have been so corrupted that, upon his accession to power, Xi Jinping launched his anti-corruption campaign. Yet no harsh repression of corruption could work without an overhaul of the one-party dictatorship and the implementation of pluralism. This brings us back to where we started, a labor movement demanding this kind of transformation is necessarily seen as the number one enemy by the party state.

Hong Kong, at least previously, did have freedom of association. Yet its labor movement remains very weak. This was partly because of the fact that decades long prosperity kept unemployment very low and workers did not feel the need to unionize. Last year’s revolt stimulated the birth of a new union movement but how much it can do is still not clear.

Au Loong-Yu’s Hong Kong in Revolt: The Protest Movement and the Future of China is out now from Pluto Press.

Photo credits: doctorho / Flickr & renfeng tang / Flickr.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/hong-kong-interview-au-loong-yu/