The many afterlives of the Paris Commune

- May 22, 2021

Paris Commune 150

Among the many reflections on the Commune, voices of the Communards themselves are often strangely absent. How did they remember this unique revolutionary episode?

- Author

The commemorative walk to Père-Lachaise Cemetery has been taking place for over 140 years. Every year during the last week of May, participants gather to walk through the streets of Paris to the Mur des Fédérés. Tucked away in the far south-eastern corner of the cemetery, the Mur represents the final resting place of some of the Commune’s last defenders — lined up against a wall, shot by the French Army and tumbled into a common grave at its base.

In May 1936, fists raised and accompanied by 600,000 supporters, the Socialist and Communist leaders Léon Blum and Maurice Thorez celebrated the electoral victory of their Popular Front coalition with their walk to the Mur. In May 1971, 100 years after the Commune and just three years after the 1968 protests that had rocked both the capital and the Fifth Republic, commemorators once again lined the streets. Some individuals tried to blow up the tomb of Adolphe Thiers, the man most widely associated with the Commune’s brutal suppression. In May 2019, thousands of gilets jaunes poured out onto the streets and into Père-Lachaise to commemorate the Commune and its stand against the French State.

There are many afterlives through which we can approach the Commune. Under the enormous weight of twentieth-century history, it has been a boon for the left and a bugbear for the right. For the likes of Blum and Thorez, it was proof that the exploited masses had the capacity to build a new socialist future. For others, it was the final, dying flicker of revolutionary insurrection. For some, it was a festival: a spectacular, anarchic celebration of alternative ways of life. For others, it was an expression of nationalist fervor: patriotic defenders facing down a German invasion. For all, it was and is an event filled with symbolic possibility, despite its short lifespan.

But what of the Communards themselves? They and their ideas are often strangely absent from these posthumous interpretations. In the political landscape of the 20th century the Commune was often more useful as a symbol of a broader ideology than as a lived event. The Communards and their thoughts were thus inconvenient or irrelevant.

What did they think of the event that shook Europe and precipitated the exile or arrest and deportation of so many of them? How did they write its memory in the years after and what kind of intellectual course did they try to chart for themselves? Did the Communards also view the Commune in terms of left and right, or somewhere between anarchism, Marxism or nationalism? Or did the excesses of its suppression leave them needing to rid themselves of its memory and somehow move on with their lives?

In fact, ex-Communards embraced the memory of 1871, writing various divergent accounts of what had happened and what had gone wrong. They placed the Commune at the heart of their political identity, using it to rehabilitate their reputation and to distinguish themselves from friends and rivals in French mainstream and international socialist politics.

Violence and struggle

Ex-Communards and revolutionaries wrote extensively about the Commune in the years after its fall. Many of these accounts focused on the trauma of the Commune’s final days. During this “Semaine Sanglante” — Bloody Week — the invading French Army fought Communards street by street to reclaim control of the capital, declaring victory on May 28. In the months and years that followed, revolutionary and radical publications dedicated considerable space to estimating how many revolutionaries had perished. As the years passed, these estimates steadily increased. By 1885, the journalist Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray was reporting in his newspaper La Bataille that 40,000 Communards had been killed.

Ex-Communards frequently relived the violence that surrounded the Commune in their writings. One of these was the veteran radical journalist and occasional deputy Henri Rochefort. Although not involved in the Commune’s government, he wrote extensively on his sympathies with it. Arrested and imprisoned in mid-May, Rochefort was one of over 4,000 suspected Communards who were deported to New Caledonia, a remote French penal colony in the South Pacific. He made a sensational escape from the islands in 1874, which turned him into something of a celebrity and was later immortalized in an Édouard Manet painting.

Following his escape, Rochefort used his public platform to bring attention to the Commune. He gave various speeches and newspaper interviews to eager journalists and exiles in the United States during his journey back from New Caledonia, and quickly re-started his own newspaper once he arrived in Europe. For Rochefort, violence defined the Commune. In an 1885 editorial, he described the Commune as “a battle of two and a half months” and foregrounded vivid, apocalyptic depictions of the Bloody Week. “Corpses,” he wrote, “floated down the Seine, and the swollen streams bathed the pavements in blood.”

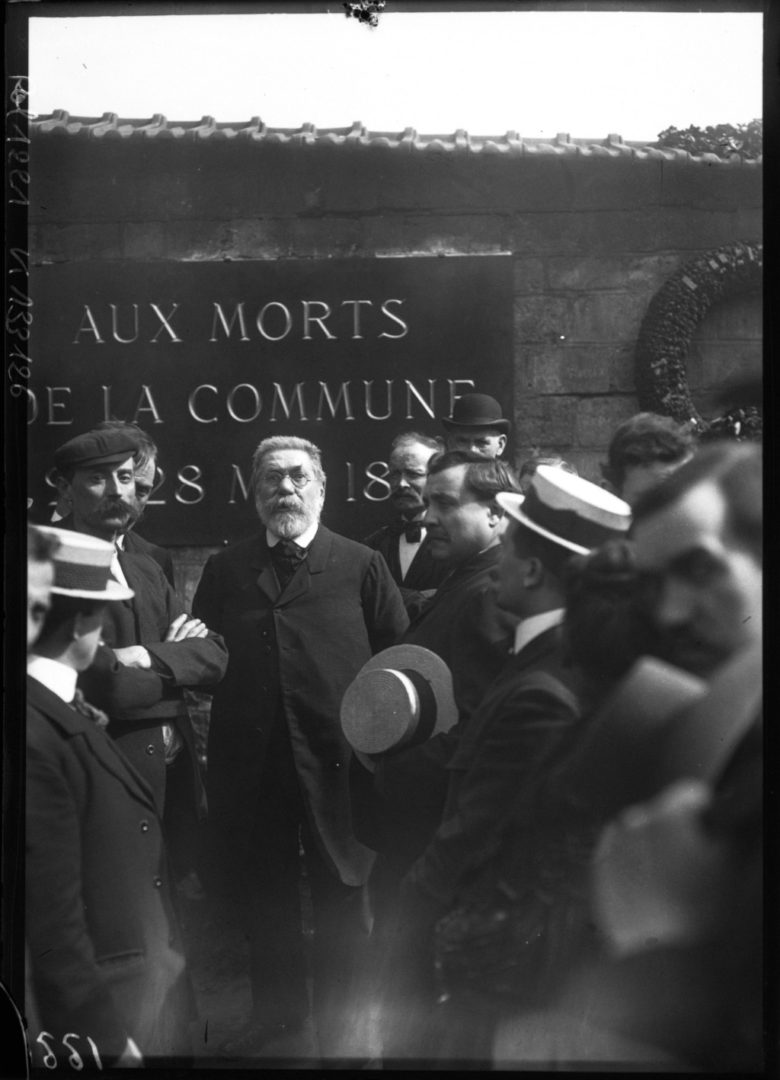

Édouard Vaillant at the Mur des Fédérés on May 24, 1908 during a commemoration of the Paris Commune. Photo: Agence Rol, source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Édouard Vaillant went even further. Unlike Rochefort, Vaillant had been present in Paris for the whole duration of the Commune and had been heavily involved in its government. He was a member of the ruling council, spearheaded the Commune’s drive for universal secular education and edited its Journal officiel. But in his later recollections he overlooked these roles, preferring instead to focus on violence — on the part of both the state and the revolutionaries — and the Communards’ own will to power. “The fighting, the struggle for existence and power was everything,” he wrote in William Morris’s Commonweal in 1885. “[T]he rest,” he went so far as to say, was “only an accident.”

This emphasis on violence and struggle was very common in ex-Communard recollections of the events of 1871. It tended to appear mainly in accounts written by former members of the Commune’s ruling majority faction. This had been comprised mainly of more traditional Blanquist revolutionaries like Vaillant who favored authoritarian measures like the creation of a Committee of Public Safety in imitation of Robespierre’s infamous Committee of Public Safety that effectively ruled France during the Terror in 1793-94. They were also more willing to use violence to get what they wanted.

Context and ideas

But this was not the only way that ex-Communards thought about the Commune. Others approached it in a more dispassionate manner. The Commune, they argued, had been flawed from its inception: it was hastily assembled, lacking in support and barely any of those involved had much experience. Jules Andrieu, a member of the Commune’s ruling council and a former employee of the Hôtel de Ville, was one of the only Communards with political or administrative experience.

In an assessment of the Commune published a few months after its fall in Edward Spencer Beesley’s and Frederic Harrison’s The Fortnightly Review, Andrieu was scathing. It had been, he argued, “staged worse than a drama on the boulevards.” The Paris Commune, in other words, had been doomed long before the army swept back into Paris in May.

These accounts dedicated a great deal of space to the context in which the Commune came about. In May 1877, Le Travailleur — a periodical run by French and Russian exiles in Geneva — observed that “the Commune is only understandable when it is explained in the context of the facts that brought it about: June [1848], December [1851], the awakening of the final years of the empire.” Similarly, the French socialist newspaper L’Égalité described the Commune in 1878 as “a complex event.” Without paying due attention to the wider circumstances and the sea of events crashing around them, the actions of spring 1871 could not be properly understood.

The most important context for ex-Communards was the Franco-Prussian War. The war had lasted for around six months from 1870-71 and involved a four-month long siege of Paris, during which many citizens and most of the political class had fled the capital. The Assemblée Nationale had retreated to Bordeaux, while the minister for war Léon Gambetta famously left via hot air balloon for Tours. The population that remained in Paris, meanwhile, had endured both the Prussian Army outside their walls and the scarce conditions within. Andrieu in The Fortnightly Review painted a picture of a lawless city: “there may have been men in military dress in Paris, but there were no longer soldiers, there was no longer an army.”

In this context, numerous ex-Communards argued that the Commune was not only justified, but necessary in order to protect the new — Third — Republic. Benoît Malon, who had sat on the Commune’s ruling council and would later go on to found the hugely influential Revue socialiste, wrote in 1880 that “[a]fter the ruin of the patrie, the Parisian proletariat…had to take up arms.” Arthur Arnould, a journalist and novelist who published a three-volume history of the Commune in the 1870s, defined 1871 as “essentially conservative against the official government.”

Communard exiles in London concurred. In 1877, a police spy reported on an address to the London exiles that had claimed,

without them [the Communards] there would be no Republic. They fought for it under the Empire and when a monarchy was being prepared on 17 March. Remember that without the dogged resistance of Paris, today you would be ruled by a Bonaparte, a Chambord, or an Orléans.

This focus on circumstances also helped them to explain why the Commune had failed. The problem had not been the Commune, Arnould wrote:

these failings are nothing to be ashamed of … They were the result of such overwhelming circumstances that even a union of geniuses would not have been able to navigate the reefs and make it into port without mistakes.

In turn, this even helped them during the 1870s to rehabilitate some of the Commune’s policies and ideas, such as reforms on night work, education and divorce, as well as the separation of church and state. Although the Commune might have failed, this was not because its ideas were fatally flawed. As Malon argued after the demise of the Commune in 1871, the revolutionaries might have been “beneath their task” but that was beside the point: “they could not do in those tempestuous days what they would have done in calmer times. Neither theories nor men can be fairly judged.” The Commune, in other words, had been full of potentially good ideas.

In contrast to the accounts that focused on violence, contextual recollections were mainly put forward by ex-members of the Commune’s minority faction. Andrieu, Arnould and Malon had all belonged to the minority, which was mainly composed of federalists, internationalists and other socialists. The fact that they had held only limited power during the Commune arguably gave them license to critically examine it in a way that ex-members of the majority, who had been responsible for its political decisions, felt unable to do. For them, the violence of the Bloody Week, which united all Communards and shifted focus onto the army and the national government, proved more valuable.

Regaining agency

The first of these interpretations — an exclusive focus on the violence of these events — is perhaps not surprising. Remembering the Commune as an event violently suppressed is familiar to us from the commemorations of the 20th century onwards. What is a ceremonial walk to the Mur des Fédérés if not a reminder of the Commune’s violent end? Linking the Commune to violence was also common at the time in republican, socialist and conservative assessments of the Commune.The historian Hippolyte Taine famously likened the Communards to “savage wolves and brigands,” and the literary critic Edmond Goncourt expressed pleasure that its demise had been so violent. These writers clearly had wildly different opinions of the Commune from the Communards themselves. But despite their differences, both foregrounded the Commune as a violent episode: an event outside the familiar boundaries of society.

The second of the two ex-Communard interpretations — focusing on structure and ideas — is subtly different from those we are familiar with. It is not surprising that revolutionary memories of 1871 would differ from those of conservatives and republicans in France who had opposed it, but they even differed from views on the left. Written in May 1871, Marx’s The Civil War in France was originally delivered as a speech to the First International. While it was by no means the only left interpretation of the Commune at the time, it quickly became the most widely known, and would go on to be regarded as the classic defense of the Commune.

Like the Communards, Marx laid into the French establishment and famously celebrated the Commune as the “glorious harbinger of a new society.” But unlike the Communards, Marx was not interested in rehabilitating the Communards’ reputations or their ideas. While he may have celebrated it as “the political form at last discovered,” he also pointed out that its ideas had failed. It was, he said, an “heroic self-holocaust.” In private correspondence Marx went even further, writing to his friend Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis that “the majority of the Commune was in no sense socialist, nor could it have been.”

Ex-Communards promoting the second of our two interpretations vehemently disagreed. For Arnould,

The idea [of the Commune] was great and just…It was the advent of a principle, the affirmation of a politics…carrying in the folds of its flag an entirely original program.

The anarchist Gustave Lefrançais, who had served on the Commune’s ruling council and fought on the barricades during the Bloody Week agreed, writing in an 1873 pamphlet that it was “precisely the solution to the social question, which grows more and more important each day, that particularly preoccupied the partisans of the movement of 18 March 1871.”

Remembering the Commune was vital for at least some revolutionaries in the years after its fall. In practical terms it had been a disaster, unceremoniously plucking them from their city and casting them into exile or deportation. But by working through their memories of it, ex-Communards managed to regain some of the agency they had lost in May 1871. They used these memories and interpretations of the Commune to set out visions of their ideas, their past and their future. Remembering the Commune was a way for French revolutionaries to distinguish themselves from both republicans like Gambetta in France and dominant personalities like Marx and Bakunin in international socialist circles.

An abundance of perspectives

The commemoration and remembrance of 1871 gives us an idea of what life was like for ex-Communards during this period. The two different interpretations — the privileging of violence or a focus on context and ideas — exposed the ongoing divisions in revolutionary circles. But their predominance waxed and waned over time, with the latter prevailing during the 1870s.

Most Communards found themselves in exile during this period and under assault from many sides in established politics and society more generally. Eleanor Marx later recalled a London landlord rescinding a booking as soon as he learned that his clients were Communard exiles.

This changed during the 1880s. In 1880, as a result of popular and parliamentary pressure on the government, a full Communard amnesty enabled both exiles and deportees to return freely and legally to France once again. The vast majority returned, and many went straight back into politics or journalism. Rochefort founded a fresh journal, L’Intransigeant, as soon as he was able to return to Paris, and by the mid-1880s ex-Communards were regularly standing on electoral lists.

Manifestation of the SFIO, the French Section of the Workers’ International at the Mur des Fédérés in 1933. Photo: Agence de presse Meurisse, source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

In this context, an interpretation of the Commune that confidently drew attention to revolutionary resilience and official repression was more useful than one preoccupied with the causes of the Commune. The evolving interpretations of 1871 therefore make visible many ex-Communards’ long journey back from exile and denunciation to the center of national politics.

This has important implications for the ways that we understand French and European politics more generally. We often think of the late 19th century as a period of increasingly confident nation states; of imperial Britain, ascendant Bismarckian Germany and a moderate Republican France, finally free of revolution. Yet the Communards and their associates were successful at re-establishing themselves in French public life. Newspapers and periodicals like Rochefort’s L’Intransigeant and Malon’s Revue socialiste ran for years. Vaillant and the syndicalist and ex-Communard Jean Allemane both served as deputies in the National Assembly and co-founded the SFIO with Jean Jaurès in 1905. Communards like Rochefort and Louise Michel maintained friendships with Republican heavyweights like Victor Hugo even in the dark days of the 1870s and thousands turned out every year for the annual walk to Mur des Fédérés.

Likewise, the abundance of perspectives on the Commune is evidence of the heterogeneity of socialism and the left. Ex-Communards operated at the heart of the international socialist movement. They socialized with Marx in London, Mikhail Bakunin and Vera Zasulich in Switzerland and were heavily involved from the 1870s in institutions like the First International. But their memories of the Commune — and the way they used them — shows that they were not swallowed up by broader power struggles like the 1872 confrontation between Marx and Bakunin that ripped the First International apart.

Instead, through their writings on the Commune, they worked busily and quite successfully to preserve an autonomous position for themselves. That this remained possible reminds us that the socialist movement was much more than its headline personalities.

Revolution in its many forms

Understanding how Communards wrote and remembered the Commune also has implications for the revolutionary tradition itself. For much of the twentieth and indeed the twenty-first century, opposition to established politics has drawn either self-consciously or unconsciously upon a distinctive revolutionary tradition. The Commune has played a central symbolic part in this. We recall Lenin’s corpse draped in a Communard flag, the Shanghai People’s Commune, Blum’s hopeful raised fist and, most recently, the gilets jaunes’ march to the Mur. These interpretations have generally agreed on why the Commune was significant.

But the content of ex-Communard writings on 1871 does not correspond at all to the directions these later uses of the Commune would take. Unlike Marx, they did not see it as a past event or the purely symbolic beginning of a new kind of society. They fought against its characterization by detractors at the time and by later historians like François Furet as the end of a peculiarly French revolutionary tradition. Nor is there much evidence that ex-Communards saw spring 1871 as a “festival” in the manner of the Situationists, Henri Lefebvre and the May ’68 protesters.

Ex-Communards wrote feverishly about the Commune in the years after its fall. They published, pushed and commemorated various divergent accounts of the Commune according to the circumstances they found themselves in. Some emphasized the Commune’s violent end, while others foregrounded its circumstances and its ideas. Rather than trying to forget about the event that had turned their lived upside down and somehow move on, they placed it at the heart of their political identity.

For ex-Communards in the years after 1871, the Commune was more than a past event to be interpreted: it was a process that was still ongoing.

Reading these texts gives us a deeper understanding of how the Commune was understood in the past, but it also provides lessons for the present and future. The Communards’ uprising failed spectacularly and scattered the revolutionary movement, but it did not wipe them off the political map or cause them to give up.

Although they might have been overlooked by later chroniclers, at the time ex-Communards were remarkably successful at re-establishing a distinctive position for themselves in national and international politics in the years after 1871, and their memories of the Commune played a key role in this. They talked about the Commune, organized walks to the Mur des Fédérés, and coordinated with more “moderate” allies in politics like Victor Hugo, the radical leader Georges Clemenceau and the leftist deputy Alfred Naquet.

In this way, they kept the revolutionaries on the public radar and helped to force an amnesty — which laid the foundation for their return to French politics, and also helped them to cultivate and preserve a political identity that was more than simply “Marxist,” “anarchist,” or “republican.”

For ex-Communards, the revolution did not end in Père-Lachaise in May 1871: the Commune represented two months of action, experimentation and ideas to be interpreted, debated and carried forward. Revolution, they implied, was not only action or violence. Revolution could take many different forms. It could be discussion, remembrance or association. These could be just as effective at bringing about political and social change.

The ways ex-Communards thought about and used their own ultimately failed uprising adds to our collective understanding of what “revolutions” might look like, and what it means to be a revolutionary.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/many-afterlives-paris-commune/