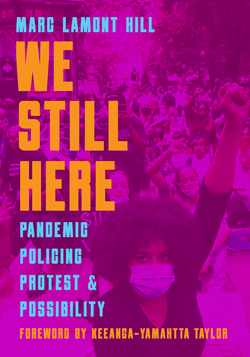

Protestors confront a line of police in riot gear in front of the Kenosha Courthouse following the shooting of Jacob Blake. Kenosha, Wisconsin - August 24, 2020 Photo: Alexandra Campion / Shutterstock.com

Anything is possible: toward an abolitionist vision

- January 23, 2021

Authority & Abolition

Abolitionism is about more than dismantling prisons. It is also about building a world with universal access to safety, self-determination, freedom and dignity.

- Author

we are each other’s

harvest:

we are each other’s

business:

we are each other’s

magnitude and bond.— Gwendolyn Brooks, “Paul Robeson”

As I reflect on the current moment, I see a widening sky of possibility. The public sphere is filled with radical voices, radical ideas and radical action. We are dreaming together, envisioning a free and safe world where we finally turn to each rather than on each other.

If we have learned anything from this moment of COVID-19, it is that we cannot survive a crisis through individual action and practice. It means nothing for me to wear my mask if you do not wear yours. It means nothing for me to establish social distance if you walk up in my space. For me to be safe, you have to be safe. This is what Martin Luther King Jr. meant when he said, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” This sensibility must guide us through not only the crisis of COVID-19 but also the crisis of living within a fascist, white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist empire in decline.

In the midst of loss and death and suffering, our charge is to figure out what freedom really means — and what our next move is to get there. I do not mean a specific tactic or strategy but the larger vision that we are to embrace. Historian Robin D. G. Kelly talks about “freedom dreams,” which speaks to the need to conjure the radical imagination in order to do the work of liberation. At this moment, we must ask ourselves, what does freedom actually look like? What does justice require? What will the future demand of us to one day declare victory?

The answer to these questions comes through an abolitionist vision. When I speak of an abolitionist vision, I am speaking to the beautifully audacious freedom dreams described by Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mariame Kaba, Joy James and so many other brilliant and courageous Black women. They teach us that, to be truly free, we must struggle to create a world where harm is met with restoration, justice is not confused with punishment, and safety is not measured by the number of human beings we imprison. They teach us that a world of police and prisons and cages is not free or humane or sustainable.

But an abolitionist vision is about more than dismantling the prison. It is also about building a world where we work together to meet one another’s needs; a world built on communities of care and networks of nurture; a world in which every living being has access to safety, self-determination, freedom and dignity.

This moment of rebellion has spotlighted the harm caused by our collective investment in blame and punishment rather than restoration and healing. All of the money spent to reform the police, enhance the punishment state and build more prisons did not protect George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. It never could. Their tragic deaths reinforced what abolitionists already knew: the problem with policing is not one of good versus bad apples. Our crisis is not rooted in the actions of particular police but the institution of policing itself, which cannot be disentangled from its origins as a mechanism for surveilling, criminalizing, punishing and killing Black bodies.

Some are leveraging this moment to call for criminal justice reform. These measures are designed to coerce us into believing the lie that the prison and its entangled institutions are salvageable, that the institution of policing is fixable, and that the system of capitalism is regulatable. But the truth has been laid bare again and again. They are not. What will secure us is embracing an abolitionist imagination that forces us beyond the posture of reform and dares us to imagine a world of new possibilities.

The architectures that uphold prisons have absorbed resources that could have been used to provide for the health care needs of a nation in crisis. Instead, the incarcerated were used to make masks and hand sanitizer that they were not allowed to use, while they got sick and workers got sick and communities got sick. In only three months, the number of COVID-19 deaths in the United States was greater than the number of US troops killed during the Vietnam War.

The prison industry must come down. We can demand a moratorium on prison construction today. We can demand the defunding of police today. We can begin to decarcerate today.

We have witnessed the possibilities of abolition during COVID-19. During the pandemic, some incarcerated people were released based on their age, health and chance of recidivism. The state also chose not to arrest and prosecute people for petty crimes. In the aftermath of the pandemic, we must sustain the same will to decarcerate. Just as the state made these moves to serve its own interests, we can continue them in the service of justice.

Of course, accountability should not be abandoned. Our communities must be protected from those who do harm. But we must ask challenging questions about the sources of the various forms of unsafety and harm we experience. We must also develop proactive measures to mitigate the harm we experience in our neighborhoods. Investment in mental health, conflict resolution, violence interruption — not to mention food, clothing, shelter, education and living-wage jobs — are the starting point for addressing and preventing the various forms of suffering experienced by the vulnerable.

Within the United States, no vision of freedom can be discussed without reparations as a beginning. US empire was founded on the exploited labor of enslaved Africans. So much of our pain, our so-called pathologies and our powerlessness is rooted in the institution of slavery. For this reason, the only way to even begin a conversation about justice for Black folk in the United States is with reparations for every single descendant of slavery.

We can no longer accept the longstanding arguments of the state that “we don’t know who to give it to,” “we can’t afford it,” or “we don’t have the resources.” As we learned during the economic shutdown that followed the pandemic, the government can always find the money, the resources and the political will to do what was previously deemed impossible. If we can find trillions to bail out the powerful, then we absolutely must do the same for the descendants of enslaved African people.

The abolitionist imagination requires the capacity to envision an “impossible” future. Yes, a world without prisons and police seems impossible. But so did ending slavery, accessing the vote, or ensuring marriage equality. Yet we have managed to achieve all of those things. When the people apply enough pressure, the state will bend. Not because it wants to, but because the people allow no other option.

The hard year of 2020 has shown us that anything is possible. We can engage in political education. We can reshape our daily practices. We can reorient our ways of life. We can radically reorganize the world.

The challenge before us is to never relent. We cannot let our mission be co-opted. We cannot reduce our radical vision to a reformist strategy. We cannot concede our right to reparations.

We cannot settle for nicer occupiers or warmer cages.

We cannot scale down our dreams. We cannot give up.

We Still Here.

Until victory. Always.

We Still Here by Marc Lamont Hill is out now from Haymarket Books.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/marc-lamont-hill-abolitionist-vision/