Black Panther, white woman: a meeting in Algiers

- October 14, 2018

Imperialism & Insurgency

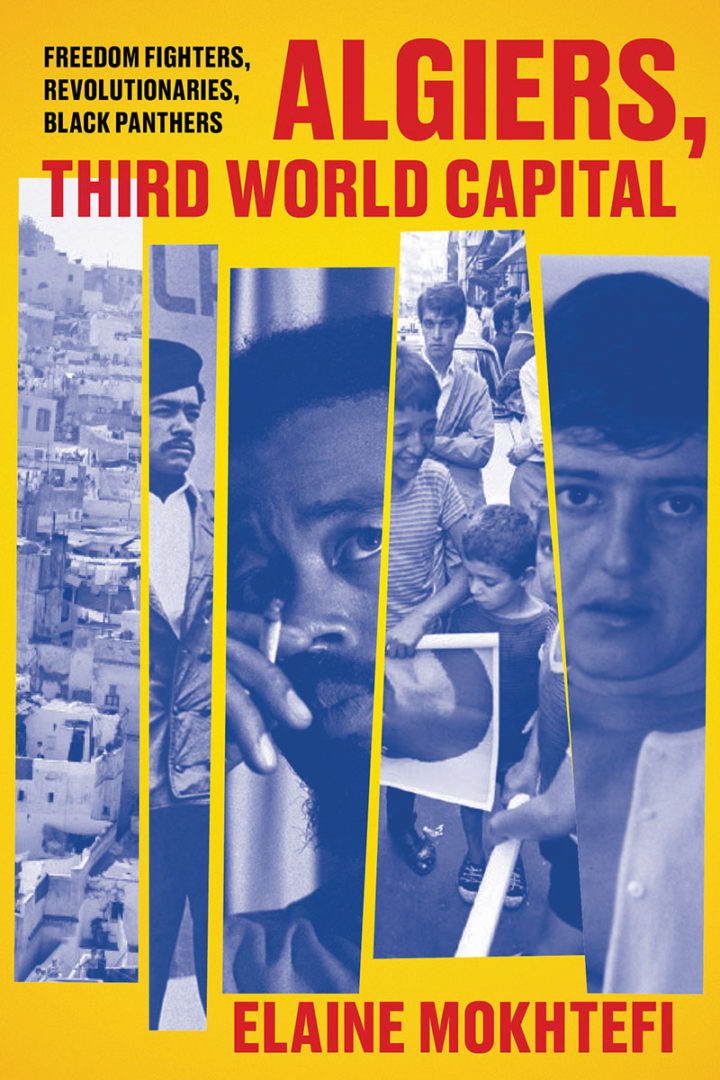

“Algiers, Third World Capital” is a fascinating story of liberation, radical politics and how one woman’s life became entangled with the Black Panthers in Algeria.

- Author

When Elaine Mokhtefi boarded a ship from the United States to Europe in 1951, aged just 23, little did she know that it was the start of a decades-long involvement in both the Algerian struggle for independence and the Black Panther Party’s resistance against the US power machine. In Paris Mokhtefi became closely involved with antiracist and anticolonial struggles focusing on Algerian independence. After a brief intermezzo back in the states, she moved to Algiers, where she would live until she was deported in 1974.

During the 1960s, Algiers had become a gathering point for leftist revolutionaries and liberation and opposition movements from around the world. It was there that her life became closely entangled with that of Eldridge Cleaver, Minister of Information of the BPP, editor of the party’s newspaper and Head of the International Section of the Panthers.

Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers (Verso, 2018) is Mokhtefi’s remarkable memoir. “For years,” she writes, “friends have urged me to tell my story. I have finally taken the plunge. I bear no grudges. I feel no rancor. This is a story with a beginning and an end.”

The following is an extract from the book.

Capital of the Third World

The Algerian war for independence had lasted close to eight years, ending officially on July 5, 1962. Algerians, from the bureaucrat to the homemaker, the fellah, the schoolchild, were acutely aware of the support received from abroad throughout the war. The local and international press had followed the yearly UN debates closely. Everyone knew the names of their representatives and which countries in the Middle East, the developing world, or the Communist bloc had supported their battle against France. They knew that John F. Kennedy, while a US senator, had directed a scathing attack against France for waging a colonial war. They knew that the ALN had trained freedom fighters from other countries during their own struggle.

Once independence was achieved, no one forgot. Algeria adopted an open-door policy of aid to the oppressed, an invitation to liberation and opposition movements and personalities from around the world. All were welcomed: the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam; the Palestinian liberation organizations; exiled politicians from Brazil, Argentina, Spain, Portugal, even neighboring Tunisia and Morocco; representatives of liberation movements in South Africa, Ethiopia, Southwest Africa, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, and Canada, with the Front de Libération du Québec; and those fighting guerrilla wars in Venezuela, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

Once independence was achieved, no one forgot. Algeria adopted an open-door policy of aid to the oppressed, an invitation to liberation and opposition movements and personalities from around the world. All were welcomed: the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam; the Palestinian liberation organizations; exiled politicians from Brazil, Argentina, Spain, Portugal, even neighboring Tunisia and Morocco; representatives of liberation movements in South Africa, Ethiopia, Southwest Africa, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, and Canada, with the Front de Libération du Québec; and those fighting guerrilla wars in Venezuela, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

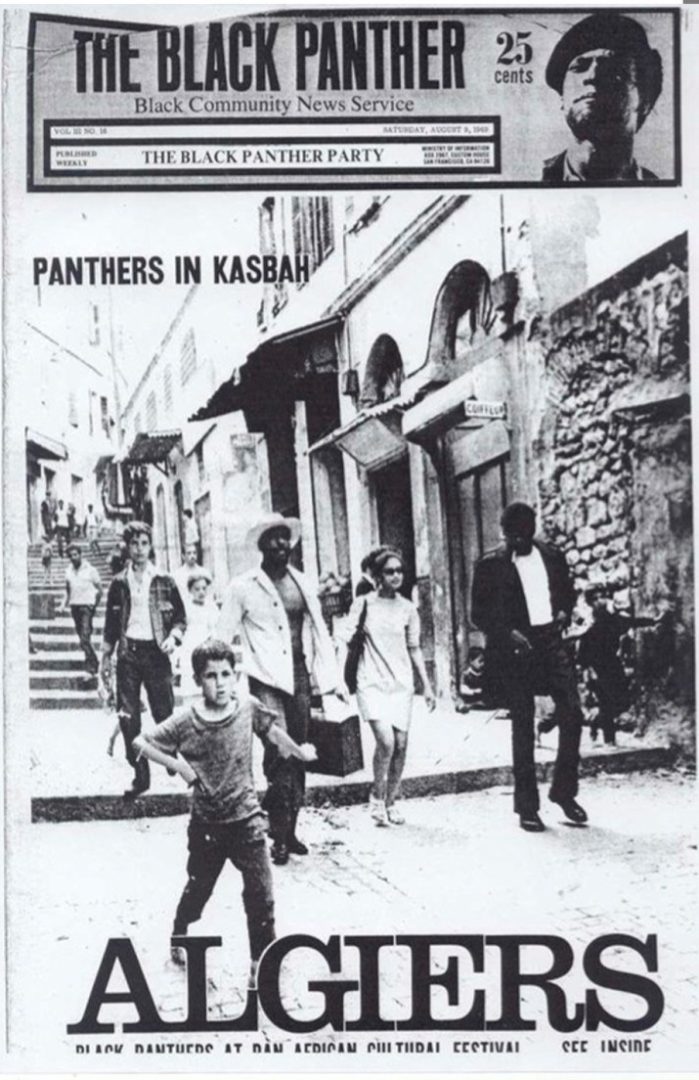

The reception the Black Panther Party received in Algiers was in line with the country’s foreign policy at the time. It has been said that recognition of the Black Panthers was only possible because no diplomatic relations had existed between the United States and Algeria since the 1967 Arab–Israeli war. I feel certain that Algeria’s treatment of the Panthers flowed naturally from its position as a Third World leader, and would not have differed had relations with the United States been reestablished.

Even before he surfaced officially, Eldridge met with Trần Hoài Nam, representative of the Vietcong. The meeting took place just as the American war against Vietnam was at a turning point: the Vietcong’s Tet offensive of early 1968 had shaken the American military and political establishment to the core. Inflamed agitation and protests at home were dogging American complacency. As a result, Lyndon Johnson had refrained from running for reelection. Since January, Richard Nixon had been occupying the White House.

Nam was a small man, slight in build, with a gentle face that belied his staunch convictions, abrasive militancy, and courage. He had great capacity for friendship, and was one of the rare foreign representatives in Algiers who developed close relationships with Algerian leaders. My own relationship with him was warm. He looked on me as the typical American, which amused me. He was anxious for my comments on events in the States; he wanted his associates in Algiers to know me and see how I lived. On Nam’s suggestion, I invited his two aides to my apartment for “American” meals.

Nam and I worked together on several projects, including putting together an “Americans for Vietnam” group with the few compatriots living in Algiers or those passing through. Green, a Black jazz pianist, was the spokesman for the group. We made a small splash in the press when a journalist from Newsweek called for an interview after seeing the communiqué I sent out over the APS wire. Nam spoke fluent French; I did the interpreting for him and Eldridge. When he was next received by President Boumediene, Nam spoke favorably of the Black Panthers.

The North Korean embassy contacted me to set up a meeting with Cleaver at its Algiers residence. There, the ambassador extended an invitation to the Black Panthers to attend an international conference of journalists (billed as the “International Conference on the Tasks of Journalists of the Whole World in Their Fight Against the Aggression of US Imperialism”), to be held that September in Pyongyang.

We were also guests at the Chinese embassy for a film showing and reception, and exchanged comments with the Chinese ambassador. “China is the friend of the American people,” he stated. “Our quarrel is with the American government and their policies.” I interjected: “The American government was elected by the American people.” My feeling was that you get the government you merit.

These were Cleaver’s first encounters with high-level foreign emissaries. He handled himself like a veteran. He was cool, reflective, intelligent, the representative of an indigenous liberation movement establishing relations with countries and movements whose goals were shared to varying degrees. Taking into account what I knew of his past—school dropout, drug dealer, rapist, ex-convict—his capacity to learn and adapt was awesome, and right on time.

As for me, it was thrilling to be involved in American politics again. My old roots were still alive, and I was ready to battle. I don’t know how the Panthers saw me, this strange white woman in Algiers, but they were certainly relieved to find someone who could speak the language and knew the conduits of power in this curious country. After all my years of adapting, first to France and then to Algeria, they made me conscious of my American self. I had not discarded it.

Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers by Elaine Mokhtefi is now available via Verso.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/mokhtefi-algiers-book-excerpt/