Photo: Ruben Hamelink

New Lines: a parliament for the Rojava revolution

- November 1, 2015

Land & Liberation

New World Summit recently started building a revolutionary public parliament in Derîk, open to all, and a true home for Rojava’s stateless democracy.

- Author

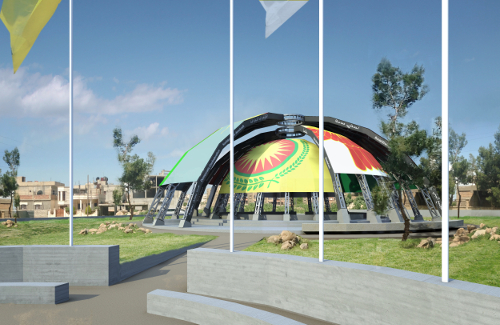

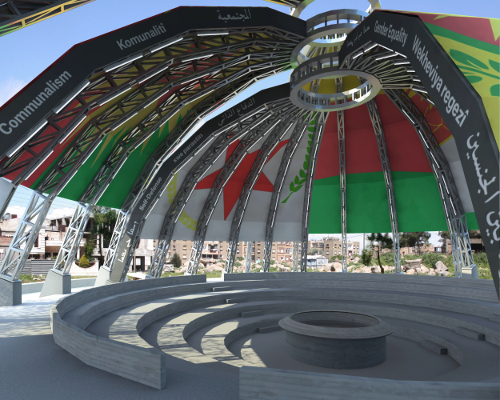

Two cranes circle above a large pit in the ground, lifting heavy, black metal arches into the air. They are covered with hand-painted words: Yeksani Regezi, Gender Equality, Xwe-Bergîri, Self-Defense.

Neighbors surrounding the construction site have walked out of their homes to see the choreography of cranes, cement trucks, and bulldozers — some of the machinery decorated with flags of political parties and councils.

Among the observers is Amina Osse, the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Cezîre Canton, watching the spectacle together with some women of the local security forces, the Asayish — famous for its public statements about the wish to auto-dissolve when the entire society has become capable of organizing its own self-defense.

Osse is one of the driving forces behind the building process, one of its co-authors. The day passes by and her silhouette turns dark. In the remaining light a large spherical shape has emerged in front of her. A constructivist globe that we hope will be a symbol for a new world in the making.

New World Summit

I am writing these words from Rojava, or West Kurdistan (northern Syria), where, for the third time since 2014, I am a guest, together with my colleagues Younes Bouadi and Renée In der Maur.

For the past years, our organization — the New World Summit — has dedicated itself to creating platforms in art institutions, theaters, and public spaces for stateless political movements from all over the world. From Berlin and Brussels to Kochi in India, we have constructed what we call “temporary parliaments,” large-scale architectural constructions in which representatives of more than thirty stateless political movements have taken the floor: from Basque, Catalan, Amazigh, Oromo and Baluch, to Tamil and West-Papuan revolutionary organizations.

Moussa Ag Assarid of the National Liberation Movement of Azawad (left) debates with Shigut Geleta of the Oromo Liberation Front (right) at the 4th New World Summit in the Royal Flemish Theater (KVS) in Brussels (New World Summit, 2014; Photo: Ernie Buts)

Today, many of these groups are blacklisted, as a direct result of the so-called War on Terror. This has resulted in the freezing of bank accounts, the enforcement of travel bans, and the cancellation of passports.

Cynically enough, this means that through the act of blacklisting, those who are already without a state are turned stateless once more, facing a double negation. Blacklisting these organizations — literally placing them “outside” of democracy — has much to do with the threat they pose to the status quo of the global capitalist doctrine.

As Tamil activist and scholar Suthaharan Nadarajah argued, the policies of blacklisting is essentially driven by a project of neoliberal state building: the demand for resistance movements to “disarm” and to engage in “peaceful democratic participation” all too often simply means that the space is to be cleared for corporate politics to take over resources and land.

Many of those declared stateless through terrorist blacklisting in the so-called War on Terror embody the living, insurgent memory of legitimate resistance against exactly these policies.

The New World Summit believes that, as artists invested in emancipatory politics, our task is to create spaces to narrate these counter-narratives: spaces where we can re-imagine and represent the world according to the stateless.

The lines drawn throughout North Africa and the Middle-East were drawn by bureaucrats and colonists. As artist Golrokh Nafisi has said, it is time to draw new lines. Not according to the occupiers, but according to the resistance. Not lines that isolate one nation from another, but lines of new shapes and forms that allow us to enact this world anew. To create a new world we need the imaginary of what that world could or should look like. As such, every political imaginary needs an artistic imaginary as well.

The revolution of Rojava

The Rojava revolution has provided the world with the political imaginary that many leftists, anarchists, eco-activists and libertarian socialists have been seeking. In mid-2011, when the Assad regime was fighting the Free Syrian Army in the south, the power vacuum in the northern, predominantly Kurdish regions of the country was filled up by the Rojava revolutionaries, who declared their autonomy.

Election for local women representatives in the City Parliament of Qamishlo, Cezîre Canton (Photo: Jonas Staal, 2014)

A collectively written text, the “Social Contract,” clarified the points of departure: Rojava was to become a non-state entity, where self-governance, gender equality, ethnic and religious diversity, the right to self-defense and communal economy would form the foundational pillars. Ever since — while in the middle of a war against the Islamic State and other jihadist groups such as the Al-Nusra Front, and surrounded by the forces of the Assad regime, Russian troops and the international “coalition forces” — Rojava revolutionaries have begun to put their new ideals of self-governance into practice.

Recent years have seen the birth of countless local parliaments and communes, self-organized neighborhood protection forces, new universities for the studies of repressed languages and cultures, the development of “jineology” (science of women), cultural centers, and a new film academy. Together they form the new social ecology known as the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava.

The Rojava revolution is more than a revolution of arms — it is a social and cultural revolution. Resulting from decades of revolutionary theory and practice developed by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the work of Abdullah Öcalan has been leading in this process. After his imprisonment by the Turkish regime in 1999, he began to theorize models of autonomy that would form an alternative to the traditional paradigm of the nation-state. Concluding that the nation-state today is nothing more than a “colony of capital,” Öcalan instead proposed a model of “democratic confederalism,” which he described as “democracy without the state.”

As is widely known today, the Kurdish women’s movement was elementary in supporting this rejection of traditional forms of statehood. PKK co-founder Sakine Cansiz described how the revolutionary movement had been “an ideological struggle from the very beginning against denial, social chauvinistic impression, primitive and nationalist approaches.”

Öcalan and Cansiz thus redefined the very notion of what autonomy means. Rather than following the terms of the colonists and their projects of state building that wreaked havoc and divide, a set of new terms arose through the practice of revolutionary struggle. This is why today we can witness the stateless democracy of Rojava.

Many journalists have described the Rojava Revolution as a surprise, as a curiosity that emerged out of nowhere. But those who visit Rojava are quickly brought to reality: on every corner, in every house or commune, the names and images of martyrs are displayed. Every inch of Rojava was fought for, in past and present.

That expression is to be taken very literally: the liberation of towns and cities occupied by the Islamic State are full of booby-traps and mines, sometimes covering hundreds of meters through serially attached explosives that cannot be but detonated to be cleared, with scattered snipers and suicide bombers left behind to achieve maximum casualties. The many young people that have to fight the way through these terrifying labyrinths are the ones who make a future for Rojava possible, very literally: one inch made inhabitable at the time.

Every idea, every achievement that formed this new democratic paradigm is thus tied to a communal memory of those who helped to bring it into practice. And still today, in Rojava, as well as in Bakûr, Rojelat, and Başûr, this sacrifice continues. The saying that “Kurds are born in struggle” is the harsh reality on which a revolutionary imaginary of a new world is founded. One cannot embrace a revolution without accounting for those who were willing to resist at the cost of their very own lives.

Living quarter of the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Amude, Cezîre Canton (Photo: Jonas Staal. 2014)

When our team of the New World Summit arrived in Rojava the first time, we felt that we were witnessing a political project that we — as artists — had hardly been able to even imagine. In a region that suffered the terror of decades of imperialist and neocolonial state-building, a radical new democratic imaginary had arisen.

Those subjected to forces that often legitimize themselves through the name of democracy re-appropriated the term, re-enforced its principles and practice, and liberated democracy from its increasing history of serving state terror, foreign wars, clientelist regimes, and covert warfare. Revolutions are also explosions of creativity; they liberate old terms and old forms, and open up the possibility for different ways of acting upon the meaning and possibilities of our being in the world. They are expansions of the imagination of what a society could become. Essentially, that is what every great work of art should be about.

Our hosts, Foreign Affairs Minister Amina Osse and Sheruan Hassan, the international representative of the Democratic Union Party, wanted to know everything about our work in the New World Summit and the temporary parliaments we created in the past years for Kurdish and other stateless political organizations.

One night, looking through the photos of our architectural constructions, Osse looked up at me and asked: “Where are these parliaments now?” I answered: “Nowhere, we construct them for the days of our international summits only: they are temporary parliaments.” With a sparkle in her eye she smiled and said: “If you would ever make one in Rojava, we would keep it forever.”

A parliament for the Rojava revolution

Design of the public parliament and surrounding park in the city of Derîk, Cezîre Canton (Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava/New World Summit, 2015)

That evening, political and artistic imaginary met. And that very same night, Osse, Hassan, and my team began to draw and develop a new public parliament for the Rojava Revolution. But this time, as Osse had suggested, it would be a permanent one.

We began drawing lines. But this time, they were not the lines of yet another state, yet another occupation, yet another wall or separation: as Nafisi wanted, they were new lines.

The first line we drew defined that the parliament had to be a public space: a people’s parliament, accessible at all times, for all layers and organizations that form the autonomous self-government of Rojava. The parliament was no longer to be separated from the public sphere, but had to become one with it.

The second line we drew defined that the parliament had to be circular; a parliament that rejects formal hierarchies between speakers and public; a parliament that embraces the fact that the revolution of Rojava rejects all monopolies of power.

Design of the inside view of the circular agora, the heart of the public parliament (Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava/New World Summit, 2015)

The third line we drew defined that the parliament had to be founded on six pillars: six metal arches, each of which would carry a foundational concept from the Social Contract that resulted from the Rojava revolution. Written in Kurdish, Arab and Assyrian these pillars would carry the foundational principles of the revolution, namely Democratic Confederalism, Gender Equality, Secularism, Self-Defense, Communalism and Social Ecology.

The fourth line we drew defined that the parliament would be covered by fragments of six flags: six organizations that form the texture of grassroots movements and coalitions that continue to shape the Rojava revolution. Six fragments of flags that, when perceived from within the parliament, form a new whole, a new flag in which the stars and suns that decorate so many of the emblems of the organizations in Rojava construct a new confederate whole.

The fifth line we drew was the overall shape that all these components would construct together: a sphere, a new world.

In many ways, we, as the New World Summit, thought that a parliament could only be revolutionary by being temporary. But through the revolutionary imaginary of Rojava, a new parliament became possible: a stateless parliament for a stateless democracy.

The Kurdish Sun

Construction site of the public parliament in the city of Derîk, Cezîre Canton (Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava/New World Summit, 2015; photo: Jonas Staal)

Now the public parliament is being built: by the hands of artists, workers and revolutionaries alike. The concrete, circular heart of the parliament has become visible. The first arches of the parliament have been erected. Artists such as Abdullah Abdul help us paint the enormous canvasses that will cover the structure.

On October 17, 2015, a delegation of twenty-seven international guests stood together with the people of Derîk and the representatives of the Democratic Self-Administration of Rojava to celebrate the parliament’s coming into being. Revolutionaries from Rojava stood side-by-side with representatives of the Scottish National Party, the Popular Unity Candidacy in Catalonia, the Amazigh World Congress from North Africa, Feminist Initiative from Sweden and the National Democratic Movement of the Philippines: an internationalist blessing for a new world in the making.

As the music started, and a dance around the new parliament began under the remaining light of the Kurdish sun, Osse stood and watched the parliament. This time she stood with many.

She had said it herself many times: “Our revolution is a revolution for humanity.” It seems that humanity is beginning to see that. We certainly do. The revolutionary imaginary of Rojava taught us the profound possibilities of a new world. And now, we, as artists, hope to make our own modest contribution to make that imaginary a reality for all.

Bijî jiyana nû ya Rojava!

Amina Osse, members of the Asayish and the building team observe the construction site of the new public parliament in the city of Derîk (Democratic Self Administration of Rojava/New World Summit, 2015; Photo: Jonas Staal)

The author wishes to thank Renée In der Maur, Dilar Dirik and Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei for their editorial support in writing this article. Also thanks to artist Golrokh Nafisi, who truly does honor to Mazou Ibrahim Touré’s saying that “Slogans are the poetry of the revolution.”

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/new-lines-a-parliament-for-the-rojava-revolution/