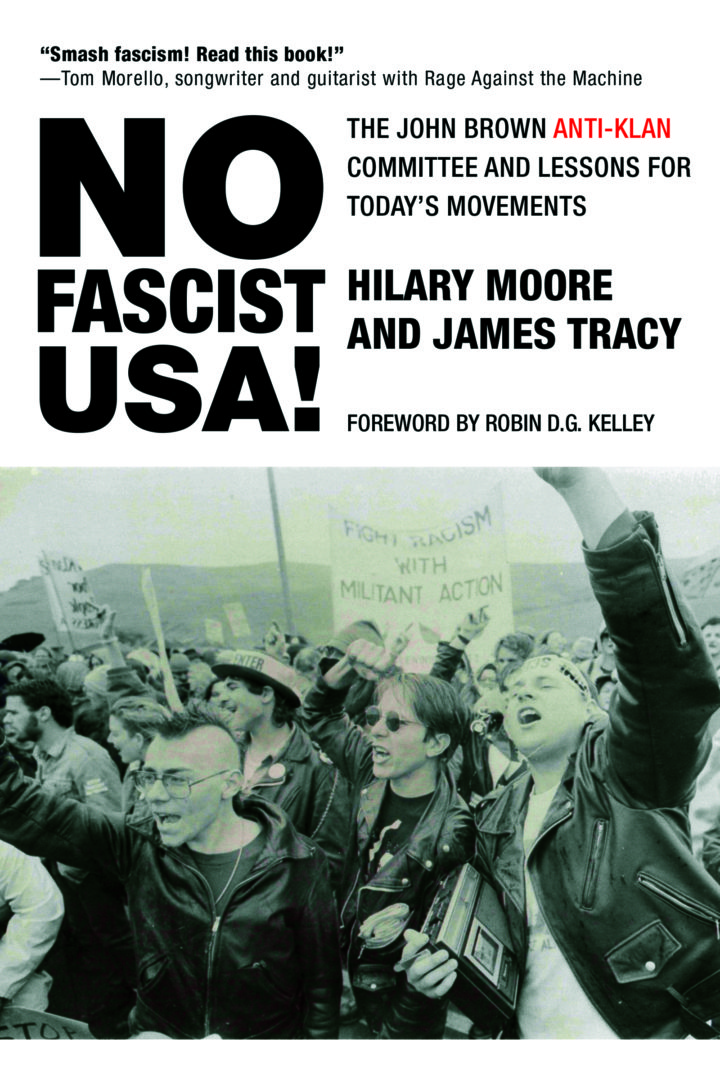

Anti-Klan protesters at a KKK rally in Chicago, Illinois, 1986. Photo: mark reinstein / Shutterstock.com

No fascist USA! Lessons from a history of anti-Klan organizing

- February 15, 2020

Fascism & Far Right

In the Reagan-era, the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee fought against fascism and racism in the US — their story provides valuable lessons for anti-fascist movements today.

- Authors

Ever since fascism first crawled out of the ideological sewer, anarchists and autonomists have been there to confront, antagonize and organize against it. You need not dig deep into past history to find evidence of this. After the mayhem of Charlottesville, Cornell West, reported to Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!:

Those 20 of us who were standing, many of them clergy, we would have been crushed like cockroaches if it were not for the anarchists and the anti-fascists who approached, over 300, 350 anti-fascists. We just had 20. And we’re singing ‘This Little light of Mine,’ you know what I mean? So that the anti-fascists, and then, crucial, the anarchists, because they saved our lives, actually. We would have been completely crushed, and I’ll never forget that.

The anarchist tradition holds many insights into the approaches to fighting of fascism. Ones that liberals and socialists would do well to consider. One, they know that relying on the state for liberation is a fool’s game. Secondly, as the Spanish Civil War shows us, that political parties of any stripe often capitulate to fascism in favor of a mythical “long game.”

In the Reagan-era, the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee (JBAKC) fought a pitched battle against the resurgent forces of fascism and racism in the United States. They were Marxists, committed to taking leadership from Third World national liberation movements. In practice, they both applied a highly creative and unorthodox interpretation of this tradition. Their approach is reflected in contemporary anti-fascist movements to this day, with considerable alignment with anarchist and abolitionists.

In the Reagan-era, the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee (JBAKC) fought a pitched battle against the resurgent forces of fascism and racism in the United States. They were Marxists, committed to taking leadership from Third World national liberation movements. In practice, they both applied a highly creative and unorthodox interpretation of this tradition. Their approach is reflected in contemporary anti-fascist movements to this day, with considerable alignment with anarchist and abolitionists.

In 1977, the JBAKC was founded in upstate New York. Many of their early members belonged to the New Left and had been committed to anti-racism and anti-imperialist actions since the 1960s. Their work was an outgrowth of solidarity activism with incarcerated people, many of whom were locked up due to their involvement with the Black Liberation Movement.

In that year, Khali Siwatu-Hodari, imprisoned at the Eastern Correctional Facility wrote to his outside allies to alert them that the Ku Klux Klan was organizing both guards and white incarcerated people. The JBAKC’s early efforts to lend support grew into a national anti-racist and anti-fascist network with chapters in Brooklyn, Austin, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other cities.

Their model prioritized mobilization and confrontation instead of vying for state intervention, an attempt to win white people as supporters of Black and Brown autonomy (self-determination). They went toe-to-toe with Nazi skinheads for the allegiance of young punk rockers and mobilized against racist graffiti campaigns in Chicago. Their slogan “No Cops, No KKK, No Fascist USA!” was taken from Born to Die, a song by the hardcore band Multideath Corporations/Millions of Dead Cops (M.D.C.). The politics of no-platforming and general aesthetics influence anti-fascist politics to this day.

We wrote, No Fascist USA! The John Brown Anti-Klan Committee and Lessons For Today’s Movements (City Lights/Open Media Publishing, 2020), in hopes of harvesting the insights and shortcomings for today’s opponents of fascism and racism. This excerpt illustrates another one of the group’s strengths: the willingness to organize against the Klan, far outside of liberal enclaves.

No Fascist USA!

The Ku Klux Klan has come to town

In the summer of 1982, residents of Austin, Texas, turned on local Channel 24 to watch Good Morning, Austin. It was like any other Thursday, except that on this day, the Grand Dragon of the Texas Klan, Gene Fisher, and Imperial Wizard James Stanfield were on the show, describing their youth training camps and showing off their shotguns and semi-automatics. That afternoon, local radio station KLBJ hosted the same Klan members, this time inviting Austin listeners to call in and chat with the Klan. Over the next two days, the Klansmen made two more television appearances. They used this media blitz to publicize their upcoming August rally in Bastrop, Texas. “We’re going to destroy Communism,” they boasted, and vowed to “take action, violent if necessary” to counter those who dared to oppose them. For these Klan leaders, three things were essential: deploying border patrols for “sealing” the border between the United States and Mexico, purchasing land for “survival camps” in preparation for an inevitable race war, and staging cross burnings. In response to their media blitz, the Black Citizens Task Force newspaper ran a headline that read: “The Ku Klux Klan has come to town.”

In 1982, the Task Force had joined up with the Brown Berets and the East Town Lake Citizens to form the Austin Minority Coalition. Their aim was to build a united force against the problems they faced in their respective communities: police brutality, high utility rates, and gentrification. The Austin John Brown Anti-Klan chapter participated in this coalition. Their efforts included driving community members to political education meetings, mobilizing white support for actions against developers’ land grabs in the barrio, investigating Klan activity, and monitoring police actions in communities of color. For instance, the Austin chapter was able to find phone records of frequent calls between CIA agent Charles Beckwith and local Klan leaders about land purchases in Bastrop, Texas, a half hour east of Austin, where the Klan burned a cross along with a casket inscribed with “reserved for commies.”

The organizations in the Austin Minority Coalition shared the belief that an active anti-racist majority could be established, and that the best way to get there would be for groups to specialize their efforts. For the Task Force, the Brown Berets, and East Town Lake Citizens, this involved building community power, addressing a community’s basic needs, and engaging in self-defense. They would have to apply pressure to moderates while also confronting paramilitary formations like the Klan. The majority of elected positions in Austin were held by white people who often spoke about opposing racism but still colluded with racist local policies and practices. For example, they wouldn’t take a position against the University of Texas’s financial support for South African apartheid and they would implicitly condone racist police behavior by supporting lengthy misconduct investigations.

In January 1983, the Klan submitted a legal request to stage a rally at the Capitol in Austin. The Austin Minority Coalition was the first community-based formation that intervened, beginning with attending a series of city council meetings. They recognized that, time and again, local governments had sanctioned Klan rallies on First Amendment grounds. During the previous year in Atlanta, the Klan, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, had won approval in federal court to march after its request was rejected by the local government, and even won a temporary restraining order pre- venting the city from interfering with the march. Weeks before the city council made a decision about the Klan permit, the Austin Minority Coalition knocked on doors to spread the word and bring people to the meetings in an attempt to reframe the debate.

A series of editorials in local newspapers urged residents to stay at home and let the Klan march. Some of the editorials also accused groups that wanted to stop the Klan of being instigators who would make things worse. In response, the Brown Berets circulated a leaflet arguing that resistance to the Klan was a matter of survival for their members. “Our plan is not to infringe upon anyone’s First Amendment rights, an argument used by public officials and the media to confuse the issue, but rather to expose the Klan’s practice of genocide, which constitutes a criminal act according to the United Nations’ Convention on War Crimes Against Humanity.”

By the time the Austin City Council meeting took place in January, there wasn’t a resident in Austin who hadn’t heard about the opposition to the rally. The council room was filled to capacity with more attendees gathered outside. The mayor of Austin, Republican Carole Keeton McClellan, delivered the decision. She prefaced her comments, “Believe me when I say we abhor, deplore, and detest the Ku Klux Klan.” She then motioned to grant the Klan a permit with the restrictions that no vehicles were allowed in the parade, and no rifles, shotguns, or other weapons were to be carried by any marcher.

Charles Ordy, the only Black council representative, agreed to read a statement from the Black Citizens Task Force about the Klan’s history of racist violence in the United States. “The freedom of speech is not absolute,” read Ordy, his voice commanding the room’s attention. “If a person is not allowed to scream fire in a crowded movie theater, we do not see how the KKK is allowed to propagate their racist theories and actions. The essence of the KKK’s ideology is white supremacy.” The Task Force’s statement received cheers and applause from the people who filled the council chambers. The decision was made to grant the Klan a permit, but the attention had succeeded in escalating public momentum to oppose it. Before leaving the council room, the Black Citizens Task Force called for a human rights march that would commemorate Malcolm X’s assassination on February 21, coinciding with the Klan’s rally.

The Austin Minority Coalition began preparations, with each member group taking on specific tasks in coordination with the others. Their collective intention was to have an anti-Klan rally that represented a wide range of the Austin community, including different ethnic neighborhoods, youth, and university students. The Black Citizens Task Force focused on dangers, given the high number of Klansmen and police expected. “Some of us wanted to scatter amongst the crowd,” recalled Terry Bisson. But others wanted to play a variety of roles, from blocking the Klan’s route options to providing security for the Brown Beret and Black Citizens Task Force. They decided on the latter.

On a sunny day in Austin in 1984, chanting from 2,500 anti-Klan demonstrators could be heard for blocks. From the beginning, the police presence loomed large with four hundred officers in the streets and SWAT teams positioned on rooftops. Protesters surrounded the seventy white supremacists — some in red and black Klan robes — marching alongside the KKK Boat Patrol formed in 1979 to attack Vietnamese fishermen. The police formed a perimeter around the Capitol building. A wall of riot police in green military uniforms protected the Klan members, who intended to march from the park to the State Capitol and back. The human rights march brought out a broad cross section of Austin, including professors, students, teachers and punk rockers. People chanted, “We’re fired up, won’t take no more!” Banners read “Abajo Con el Klan” and “Reagan and the Klan Go Hand in Hand.” The massive crowd fell silent when Black Citizens Task Force leader Velma Roberts took the bullhorn. “We have been discouraged by people saying we should ignore the Klan,” she commanded. “We think silence is consent. And if we decide to ignore the Klan, then they come into our community and march.”

Terry Bisson remembered the visceral sense of being in a crowd unified against the Klan and its supporters. The goal to drown out any Klan speeches was met. The plan to block the Klan’s march route, however, didn’t work, and Coalition leadership had to improvise. Bisson recalled the strong sense of solidarity among the protesters throughout the day, from sharing food and water to helping each other avoid arrest. “I threw a huge bolt, almost hitting [a] Klansman in the head. I was immediately thrown to the ground by plainclothes police.”

Lessons for today

The business of confronting organized fascists and racists in the streets is necessarily an act of risk and bravery. It is important then to peel away from the temptation to romanticize the past. What lessons can the JBAKC’s history provide us today?

The JBAKC put forward a type of “anti-fascism without illusions.” They were crystal-clear that fascism in the United States was not anything new. Right-wing backlash pivots around racist conceptions of migration in the United States. Many of these narratives stem from Nativist politics, placing foreigners as the evil other and collapsing whiteness with citizenship. No Fascist USA! shows how white supremacist organizations, such as the Ku Klux Klan, have adapted these tropes in the last two hundred years and how anti-racist groups in the Anti-Klan Movement responded in the 1980s.

The organization also developed ever-evolving strategies. They attempted to go beyond simply fetishizing street confrontations (which they embraced as a necessity) to experiments of following “leadership from below,” or coordinating with the communities that are most impacted by systemic oppression in order to uplift their vision, methods and wisdom. The John Brown Anti-Klan Committee formed in response to incarcerated leaders of the Black Panther Party and Puerto Rican Independence movement, as they were under attack from Ku Klux Klan members from inside prison.

Instead of promoting guilt based politics, the JBAKC sought out ways to deploy white people effectively in the overall quest for liberation. This meant choosing to take on certain kinds of risks, talking to other white people about anti-racism, fundraising or accessing funding, and making lasting connections to build a strong network of white people committed to anti-racism and anti-fascism.

Ultimately, the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee was a living experiment of radicals confronting the far-right in the Reagan era. Their decentralized network allowed them to build projects that responded to the demands of cities they mobilized in. As today’s far-right seems poised to expand no matter who sits in the White House, we would do well to consider the JBAKC’s legacy.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/no-fascist-usa-lessons-from-a-history-of-anti-klan-organizing/