Panthers forever: revolution at home and in exile

- July 9, 2020

Race & Resistance

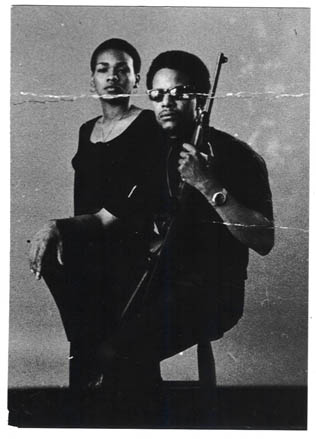

Black Panthers Charlotte and Pete O’Neal reflect on their lives as revolutionaries in the US and Tanzania, after living in exile for over 50 years.

- Authors

Revolutionary socialism is a quest for freedom, justice and equality through the destruction of capitalist oppression by any means necessary, often including armed struggle against the state.

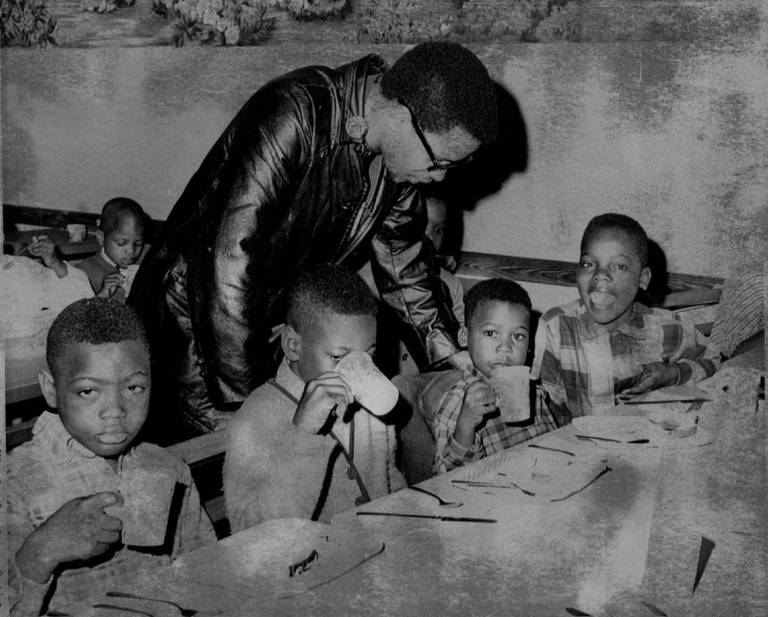

In the 1960s and 70s, The Black Panther Party (BPP) represented the vanguard of the revolution in the United States. It promoted armed self-defense, a sophisticated educational agenda and outreach to Black communities as well as other oppressed groups in the US and abroad via the Black Panther newspaper. The Panthers’ community work and organizing included free breakfast for school children and health clinics programs.

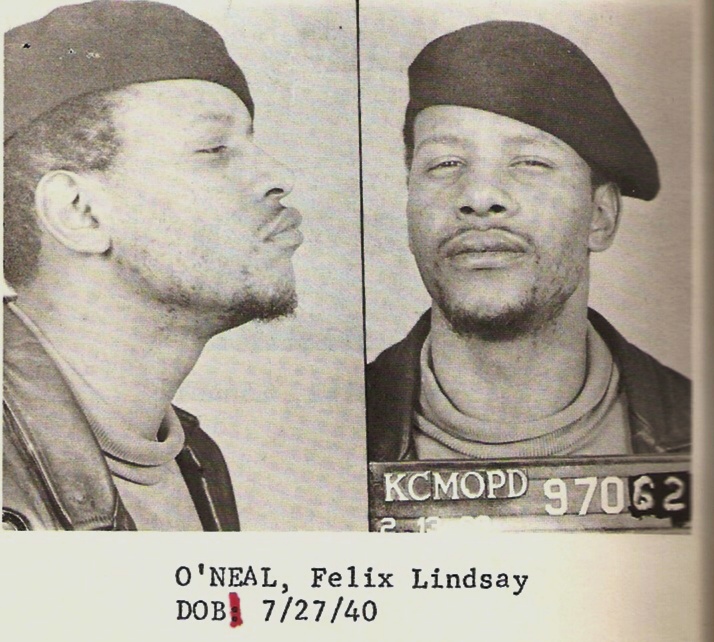

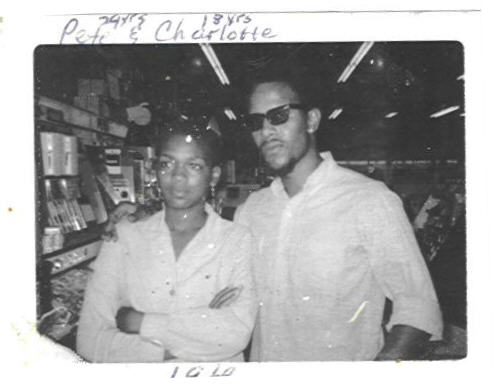

At the age of 29, Pete O’Neal founded the Kansas City chapter of the BPP, soon to be joined by the 18-year-old Charlotte Hill. Committed to challenging the white supremacist power structure in the state of Missouri, Pete soon became a target of political persecution at the hands of establishment darling Clarence Kelley, the police chief of Kansas City, who would later move on to become director of the FBI.

In 1970, Pete was sentenced to four years in prison on dubious charges for illegal gun transport. Rather than going to jail like many of his fellow BPP members, Pete seized an opportunity to escape. Together with Charlotte, they fled to Algeria, finding refuge at the BPP international division in Algiers, before moving to Tanzania two years later.

The O’Neals currently live in the village of Imbaseni near Arusha, Tanzania, where they founded the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) in the early 90s. They have been engaged in farming and community service reminiscent of the programs pioneered by the BPP.

In the following interview, Pete and Charlotte O’Neal speak about their revolutionary trajectory and share thoughts on the current uprisings in the US and the world.

Yoav Litvin: How did you get into the BPP?

Pete O’Neal: As a young man, I was not a very progressive person. I made a living on the streets. I accidentally stumbled into the BPP and it was an epiphany for me.

I got into a confrontation with the police in Kansas City, which led to a clash with Clarence M. Kelley, the police chief of Kansas City who replaced J. Edgar Hoover as the director of the FBI. He became my nemesis, my arch enemy.

In late 1968, I traveled to California to meet BPP leaders Bobby Seale and David Hilliard — Huey Newton was in jail at the time. I was enraged with police misconduct against me and general corruption in Kansas City and sought revenge.

Seale and Hilliard said, “brother, that’s not what the BPP is about. We’re not about settling scores, we’re trying to build something that would change the lives of people here in the United States and around the world.”

They invited me to spend some time with them and other Panthers, learning about the organization, their principles and guiding ideologies. I had lived and been to prison in California, so I was no stranger to those parts and I decided to stay for several weeks. We spent hours discussing Che Guevara, Mao Tse-Tung and a host of luminary revolutionaries, their sacrifices, goals, agendas and accomplishments for the people. I was deeply affected by these teachings and became a believer in the same manner as a born-again Christian.

They invited me to spend some time with them and other Panthers, learning about the organization, their principles and guiding ideologies. I had lived and been to prison in California, so I was no stranger to those parts and I decided to stay for several weeks. We spent hours discussing Che Guevara, Mao Tse-Tung and a host of luminary revolutionaries, their sacrifices, goals, agendas and accomplishments for the people. I was deeply affected by these teachings and became a believer in the same manner as a born-again Christian.

I headed back to Kansas City on fire. I cut ties with all the negative people and activities I had been involved in. Within six months, I headed the Kansas City chapter of the BPP. It became my salvation and has been so for over 55 years.

My confrontation with Clarence Kelley continues, even though he’s since passed away. To this day, one book — Kelley’s — faces outward on my bookshelf with his portrait still staring at me. I want Kelley to know that I have not given up on the fight and am still firmly committed to the revolution.

Charlotte O’Neal: I was born in 1951 in Kansas City, Kansas, during the blossoming of the Civil Rights movement. My parents would discuss politics with friends and they encouraged me and my two siblings to be proud of who we were.

When I went to Junior High School it was my first time around white people. The school was newly integrated and so I experienced racism on a regular basis. I did very well in school, though I always had discipline problems.

When I was 17, I was selected and joined the Kansas City High School of Human Dignity. I met people who were much older and wiser than me; teachers and doctors and college students. I loved it. We would study together and discuss African history and the diaspora. It opened up a door in my mind to my African ancestry and reality.

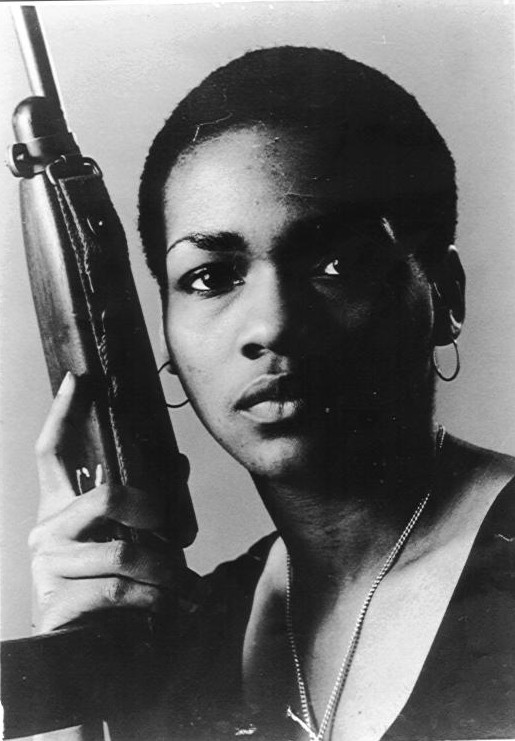

At that time, I began seeing all these beautiful, empowered Black brothers and sisters — members of the BPP — posing with berets, shades and leather. I started cutting out photos and articles and pasting them on my wall. One of those images was of Pete O’Neal, who I never expected to meet — let alone spend the rest of my life with.

At that time, I began seeing all these beautiful, empowered Black brothers and sisters — members of the BPP — posing with berets, shades and leather. I started cutting out photos and articles and pasting them on my wall. One of those images was of Pete O’Neal, who I never expected to meet — let alone spend the rest of my life with.

I graduated and was inducted into the National Honor Society, receiving a scholarship that could enable me to attend Medical School. However, in 1969 at the age of 18, I ran away from home to join the BPP in Kansas City, Missouri.

Back then, us young Panthers lived communally, in “Panther pads.” I hadn’t met Brother Pete yet, because he was on a month-long tour of several BPP branches in Nebraska, Oklahoma and other locations.

When we first met, I was high on psychedelics, experimenting along with seven or eight other young Panthers. Pete was furious and disciplined us. I stood up for myself but he locked us in a room, a little Panther jail, until we all came down. Conduct and décor were vital for BPP members, and in retrospect I completely agreed with Pete’s stern chastening.

A couple of days later we saw each other again and the rest is history. We’ve been together 50 years since.

I became a lifelong Panther when I first learned of the breakfast for schoolchildren program, in which we gathered donations of food and fed hungry children. I continue to embrace the spirit of volunteering, which was one of the cornerstones of what it meant to be a Panther. The entirety of our work was voluntary — it was an expression of community love. To this day, when I go to Kansas City, I meet people who benefited from it and thank me for our work.

As a woman, what was it like to be a BPP member?

Charlotte O’Neal: Theoretically, there was supposed to be equality between the sexes in the BPP. Though sometimes it was taken for granted that we were going to do the housekeeping or cooking. We Panther women had to fight against that, constantly.

Party members came from all walks of life. Some were conscious, some were chauvinistic, some were from the street and had their own street philosophy, while others were educated college kids.

On the other hand, whether you were male or female, you received weapons training, served as the officer of the day, and had to be out selling papers or flipping pancakes for the children.

What does the image of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in black leather, holding guns represent to you?

Charlotte O’Neal: Huey used to say a revolutionary has to have love for the people, otherwise why would you be out there? Self-defense was a means of demonstrating a love for the community. The guns were used to defend family and friends from the brutality and abuse of the state. Defense naturally came along with community service; breakfast programs, free health clinics and more.

Talk about your political persecution and how it led you to flee the US.

Pete O’Neal: In the late 60s, law enforcement was determined to prevent the continued fortification of the BPP as a force in the Mid-West. We were Black revolutionaries smack in the heart of the white supremacist, settler colonial country — in the bible belt — and the Kansas City chapter was rather influential.

We received some incriminating information about the Kansas City Police Department from an ex-policeman and decided to expose it. The evidence showed police were confiscating guns and giving them to right-wing organizations such as the John Birch Society, Ku Klux Klan and the Minutemen. It shone a very unflattering light on the establishment’s darling boy — police chief Clarence Kelley — and his entire crew.

We made a big stink of the whole story, and the media picked up on it. The politicians, including Kelley, convened a Senate hearing in Washington DC to discuss it, and several of us Panthers crashed the session. They pulled a fast one and locked us in a room under the guise that a stenographer was being fetched to record our allegations. They unlocked the door hours later, after the meeting had adjourned.

Black Panthers carrying guns scared them to death. After Panthers stormed the California state capitol in 1967, they passed the Gun Control Act of 1968, the only gun control legislation supported by the National Rifle Association (NRA).

Three weeks later, to the day, I came out of my office and the Kansas City SWAT team arrested me, backed up by the FBI. They accused me of causing the transportation of a shotgun across the Missouri-Kansas state line — a ridiculous charge — after the gun was confiscated from another Panther. In fact, years later, an attorney attempted to use my case as a precedent and the judge ruled that the ruling in my trial was an error.

The prosecution in my case concocted three charges that would have afforded me 15 years in jail. In October, 1970, they ended up convicting me on just one, sentencing me to four years in jail.

The standard establishment modus operandi was to jail a revolutionary for long enough to fabricate charges which would keep them locked up for decades — if not for life.

The judge allowed me to stay out on bond during the appeal process. We fled with the help of white lefty comrades out of New York City. Charlotte and I were provided a safe house, and passage out of the US. I still believe the prosecution willingly let me go. They knew I spelled trouble and wanted me out of their hair.

One of my last memories of the US was our ride to the airport. The comrade who drove turned on the radio and little 12-year-old Michael Jackson sang “I’ll be there.” We thought we may be gone for up to two years, though it was twenty years before Charlotte returned, and I have not been back in the US since.

When we arrived at the airport, I asked Charlotte whether she was certain she wanted to come along. After all, she had a full scholarship to medical school and a bright future ahead. She rejected any path other than coming along in a bid to continue the struggle for the people. She used to call me Brother Chairman and I remember she said, “no, Brother Chairman. I’m down for doubles, I’m down for it all the way.”

We got on the plane, paranoid as hell, and spent several months in Sweden before flying to Algeria, to meet up with Eldridge Cleaver or “Papa Rage” as he was known. This had been after the fratricidal split within the BPP, which caused a lot of people to die. My comrade Geronimo Pratt told me to seek out Eldridge who was on our side of the split.

When we arrived in Algeria I didn’t know what to expect. I gave Charlotte all the money we had and went to see Eldridge. When I rang the doorbell, Cleaver answered. He was an imposing dude, and though I was scared of nobody, when he opened the door I thought, “shit, here we go now.” When I introduced myself he said, “where have you been?” I found out my mother had written him over 20 letters asking for me. They welcomed us with open arms and we remained in Algeria with the BPP for two years.

The BPP in Algeria had relationships with most of the exile revolutionary movements, such as the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), the African National Congress (ANC), Palestinians fighting the Zionist regime and many white revolutionary organizations, which had people in exile. That said, these relationships were mostly cosmetic as we were all trying to take care of our particular struggles first and foremost.

The BPP in Algeria had relationships with most of the exile revolutionary movements, such as the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), the African National Congress (ANC), Palestinians fighting the Zionist regime and many white revolutionary organizations, which had people in exile. That said, these relationships were mostly cosmetic as we were all trying to take care of our particular struggles first and foremost.

The Algerian thing was good while it lasted, but things started falling apart. Some folks unaffiliated with us hijacked planes and cast a very unflattering shadow on our work.

We started to leave in increments. One brother went to Zambia, where he died in 2010. Another went to France and died in 2011. Geronimo Pratt came out here [to Tanzania,] and died in 2011. I’m just too tenacious to die. My story is presented in full in the book Black Panther in Exile – The Pete O’Neal Story by Paul J. Magnarella.

How did you arrive in Tanzania, of all places?

Pete O’Neal: We came to Tanzania in 1972. We now live between Mounts Meru and Kilimanjaro, 30 miles, as the crow flies, from the latter.

Originally, I did not want to come to Tanzania. I wanted to go back to Sweden, get back underground and head home to the United States to join the revolution. Every Panther who went that route ended up in prison, some for 25 years or more.

Our Kansas City Minister of Information convinced us to come down here to Tanzania. Charlotte talked me into it, and it was one of the best moves we ever made. When we arrived, all I saw was the mud and the rusted tin roofs. I felt like I jumped from the frying pan into the fire. On the other hand, Charlotte was in heaven. We were like the two characters from the Dale Carnegie quote: “two men looked out from prison bars, one saw the mud the other saw the stars.” It took me a while but eventually I came to see the stars, too.

Charlotte & Pete O’Neal: Like pioneers, we started out homesteading. When we first got here, there was no running water or electricity. We were out in the boonies; buffalo and hyenas would run down the road and get into our shamba (farm). We used machines to pulverize termite mounds, mix with sand, water and a tad of cement to create building blocks. We raised chickens, made cakes and cookies and worked our butts off building windmills, milking cows and learning skills we hadn’t imagined we would ever acquire. With the help of people in our village, we started farming beans and making sausages, which we sold to Tanzanians for 15 years. Though Charlotte is a vegetarian for over 40 years, we used to hunt together.

The elders in the village of Imbaseni were impressed by our achievements and sent the youth from the community to apprentice with us. The elders gave us a plot of land and that’s where we built our first center, approximately three miles from our current one.

The jewel in the crown of the Black Panther Party was its community work. Everything we do at the United African Alliance Community Center (UAACC) is a representation of that work. It continues to inspire people in the United States and the world.

We run the community center and offer free community education; classes in English, empowerment for women through arts and music, computers, video production, design, sowing, photography and more. Charlotte conducted a papier-mâché furniture project with local women. We manage the Leaders of Tomorrow Children’s Home to help improve the lives of orphans and children from extremely disadvantaged homes in Tanzania. We have raised 28 children of all ages, from toddlers to university students, for the last 12 years with extremely limited resources.

We run the community center and offer free community education; classes in English, empowerment for women through arts and music, computers, video production, design, sowing, photography and more. Charlotte conducted a papier-mâché furniture project with local women. We manage the Leaders of Tomorrow Children’s Home to help improve the lives of orphans and children from extremely disadvantaged homes in Tanzania. We have raised 28 children of all ages, from toddlers to university students, for the last 12 years with extremely limited resources.

We have two blood children together, while our kids here are our extended family.

Florynce Kennedy, the Black radical feminist and New York City lawyer once commented, “a grandmother can bake a pan of cornbread for the civil rights struggle or make some iced tea and her action becomes an extremely revolutionary act.”

The work we’re doing here, putting our history and present day work in the best possible light, is our natural trajectory as revolutionaries.

How do you feel about what is going on in the streets right now? Has anything changed in the United States since the Panther days?

Pete O’Neal: I think the youth has opened the door to something very beautiful and inspiring and I believe it will bear fruit.

Many decades ago Malcolm X said something that only now I fully comprehend:

America today finds herself in a unique situation. Historically, revolutions are bloody, oh yes they are. They have never had a bloodless revolution. Or a non-violent revolution. That don’t happen even in Hollywood [laughter] You don’t have a revolution in which you love your enemy. And you don’t have a revolution in which you are begging the system of exploitation to integrate you into it. Revolutions overturn systems. Revolutions destroy systems. A revolution is bloody, but America is in a unique position. She’s the only country in history, in the position actually to become involved in a bloodless revolution… today, this country can become involved in a revolution that won’t take bloodshed. All she’s got to do is give the black man in this country everything that’s due him, everything.

When I was younger I did not believe that. But the BPP planted the seeds; now it’s time to sow.

Point seven of the BPP ten-point program was our raison-d’etre:

We want an immediate end to Police brutality and murder of Black people, other people of color, all oppressed people inside the United States.

For over 50 years in exile I’ve watched the brutality and abuse of Black people continue. And it’s become clearer to the entire world with the availability of recording technology.

The murder of brother George Floyd really lit the fuse for many young people. They have inspired and motivated people around the world to rise up against white supremacist, capitalist oppression. Back in the 60s, it took the Vietnam war to produce comparable upheaval. The rise in consciousness nowadays is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

I would not be so presumptuous as to tell the organizers how to run their party. However, I would strongly suggest that they plan beyond the demonstrations and the protests because they are not sustainable in the long run. Something bigger must drive and inspire the masses.

Charlotte O’Neal: I feel proud, like the torch is being passed. It is beautiful. I have young people contacting me all the time, asking me for advice. I see their spirit and it’s a mirror of mine. I feel the revolution is in good hands. I have a lot of hope. It’s like the 60s are back!

Police were formed as slave catchers, patty rollers, and the racist culture just continued into police departments. The only reason it seems like an escalation is because people are able to document it. When I see young people of every color shape and form, conscious people coming together it makes me overjoyed.

The BPP had white, red, yellow, black, brown and pink comrades. And they were really our brothers and sisters. To this day I call everybody brother and sister until they show me otherwise. That’s what we learned as members of the BPP.

Is love going to bring down this deeply entrenched, capitalist, racist systems or do we need to accept that violence is part and parcel of the revolution we seek?

Charlotte O’Neal: It is unfortunate, but violence seems to wake up those in power. Violence and financial decline, which often go together. As a mother, a nurturer and a warrior woman, it is very distressing; I don’t want to see children traumatized by violence.

As Black Panthers we spoke of community control of police. Now, this radical concept is entering the mainstream. Defunding police would free up money to fundamentally change communities.

Art is a powerful, non-violent tool of conveying revolutionary messages, as well as personal expressions of love. As an artist myself, I’ve participated in a range of solo and collaborative works highlighting oppression and the power of communal cooperation, most recently with students from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in a project titled Contested Homes: Migrant Liberation Movement Suite.

The spoken word in the following includes excerpts from my poem “Paying Homage in Our Own Way,” which is from my first poetry book titled Warrior Woman of Peace:

What insight can you afford as a fugitive? Are you still seeking a pardon after all these years?

Pete O’Neal: I wish to inspire people to think about political prisoners. For example, BPP members and Omaha natives Edward Poindexter and Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa (slave name: David Rice) were convicted of murdering Omaha Police officer Larry Minard in a highly controversial case some claim was a result of COINTELPRO operations (aka the Rice-Poindexter case).

In fact, Mondo denied any involvement in Minard’s death and was in Kansas City at a rally to support me against the gun charges I was facing at the time. The state’s parole board and human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have recommended their release; though local politicians have refrained from doing so.

In 2016, Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa died in custody and I sent his ashes to the top of Kilimanjaro. As long as I have been in exile Poindexter has been sitting in a cage.

I have never ever asked for a pardon. My cousin Emmanuel Cleaver is a congressman and I tell him and everyone else that I’d prefer a pardon for a political prisoner. I’ve been blessed for the last 50 years to wake up each morning under a beautiful African sun. I’ve made babies and raised them. Meanwhile, comrades have been locked up in cages.

If you had the opportunity to speak with the leaders of the current uprisings in the US and the world, what would you tell them?

Charlotte O’Neal: One of the most important things is an emphasis on mentorship and the power of positive example. I think it is crucial to build up the confidence of the young people on the streets, so that they know where to direct their rage and love. I think it is very important to teach young people practical skills. It’s not all about being on the megaphone or even marching. I would emphasize the importance of community work and urban gardens as manifestations of revolutionary work. We have to return to a culture of respecting the land, of respecting water, the earth and appreciating our African traditions and spirituality.

Pete O’Neal: Listen here, revolutionary brothers and sisters. Charlotte and I are almost ten thousand miles away, but our hearts are with you. We march with you in spirit! We are in total solidarity with what is going on and we remain part of the revolutionary process.

The BPP was the vanguard of the revolution. Now, you are the vanguard, we will support you in any way we can. Count us in.

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Malcolm X Movement.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/panthers-forever-revolution-at-home-and-in-exile/