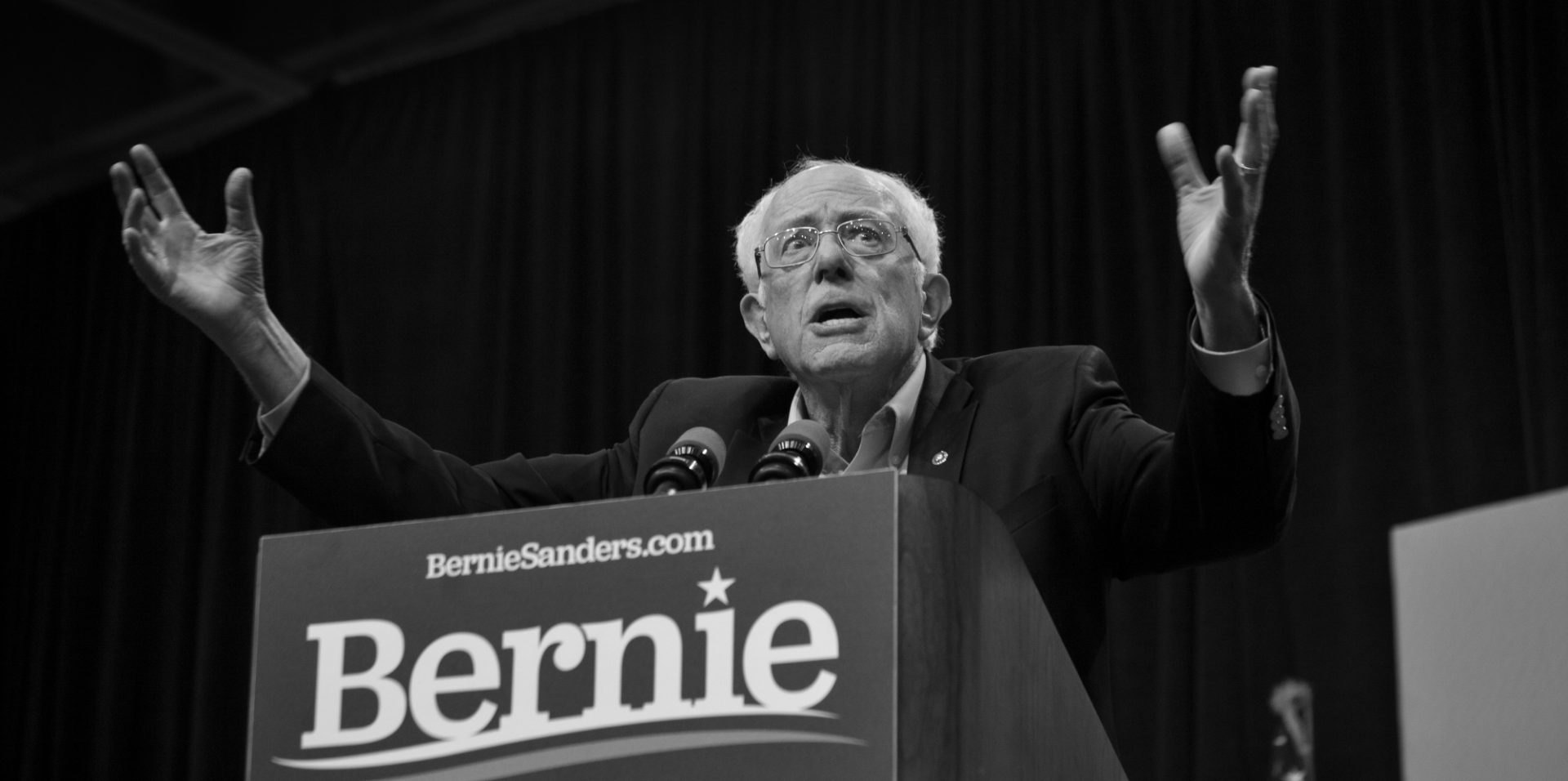

Bernie Sanders at a rally in St Paul, Minnesota. March 2, 2020. Photo: Lorie Shaull / Flickr

What went wrong? Reflections on the 2020 Sanders movement

- September 1, 2020

Capitalism & Crisis

The failures of the Sanders campaign reveal the specters of success. But the left cannot learn from its mistakes if it refuses to admit that it made any.

- Authors

By almost any metric Bernie Sanders was better positioned to win the Democratic nomination in 2020 than he was in 2016. He entered the 2020 race with far greater name recognition — hovering over 90 percent in early states — greater funding capabilities — eventually raising over $200 million — and a better organized ground-game with knowledge of its previous shortcomings — a poor 2016 performance among elderly Black voters.

And yet, also by almost any metric, the Sanders campaign was less successful in 2020 than 2016. Whereas in 2016 Sanders posed a formidable challenge to the establishment powerhouse Hillary Clinton — amassing 43 percent of the popular vote and earning various concessions from the DNC platform — in 2020, as the recent Democratic National Convention made clear, this was not the case. Sanders lost several states that he previously won, including Minnesota, Michigan and Washington State, while dramatically underperforming in rural counties throughout the nation.

Not only was Sanders unable to expand upon his 2016 base, but it in fact saw significant erosion: he lost non-affiliated voters, independent voters and almost all demographics over 40 to an array of other candidates. Any hope of meaningful leverage, let alone victory, is long gone.

What this brings us to, then, is the unpleasant but necessary question: what went wrong? Although some on the left reject this query as “cynical” and “pessimistic,” it is a question that the left, especially one that seeks to win, must confront. In relative and absolute terms — that is, compared to both 2016 and to the ultimate aim of gaining power — the Sanders movement came up short of its goals.

Yet, while the usual suspects are there to blame — the mainstream media, the unified establishment, the corporatist DNC and so on — if the left is to move past what Glen Greenwald calls liberalism’s “pathological” refusal to reflect (read: Clinton 2016), then it must face its own failures head on. Explanations that rely upon scapegoats and obvious extrinsic factors, such as establishment animosity towards the left, simply will not do. Instead, for a movement that aspires to power rather than nostalgic laments, an internal critique focusing on things that are in its control is required.

What follows is a diagnosis of the movement’s shortcomings, missed opportunities and capacities for further improvement. This, of course, is not to say that Sanders failed to make important gains, but rather to insist that there existed the unfulfilled potential for greater gains.

The opportunity for an authentic left movement — today especially — is ripe, as COVID-19, systemic racism, widening wealth inequality and the unraveling of the neoliberal order more broadly exacerbate generalized discontent with the status quo. The question is how to capitalize upon and advance where the so-called populist Sanders left fell short. The answer begins with a proper diagnosis.

BAD STRATEGY: THE DNC AND THE PMC

The Sanders campaign strategy differed significantly from 2016 to 2020. Compared to its previous instantiation — whose electoral success was rooted in a nontraditional Democratic base, with particular strength with rural counties and independent voters — the 2020 version catered far more to two particular groups: the establishment wing of the democratic party, namely centrist never-Trumpers, and the left-liberal professional managerial class, or the so-called “PMC,” consisting of university elites, middle-class managers and establishment media figures.

These shifts came to fruition, first and foremost, in the stance the campaign took towards President Trump. Although the campaign purported to aim beyond strictly anti-Trump rhetoric, Sanders largely acquiesced, whether through pressure or genuine belief, to the DNC’s Trump narrative. Nearly every time Sanders spoke at debates, town halls and rallies he referred to the president as “the most dangerous in US history,” ad nauseum repeating the party line that Trump is racist, sexist, xenophobic, and, most notably, a “pathological liar.”

While, of course, many of these descriptors are accurate, Sanders’ compulsion to repeat them at the beginning and end of each debate, as well as the ahistorical suggestion of Trump’s singularly dangerous status, was fully in-line with elite party politics — Corey Robin, for instance, locates Trump in a tradition of standard conservative thought and notes, in fact, his relative political weakness when compared to Reagan and Bush Jr.

When asked if he would unconditionally support the Democratic nominee at the end of the primary, regardless of whether the nominee was opposed to any semblance of progressive legislation, Sanders always answered in the affirmative, endorsing the DNC’s calls for party unity. As Sanders exclaimed during his post New Hampshire victory speech, “no matter who wins, and we certainly hope it’s going to be us, we’re going to unite together…We are going to unite together and defeat the most dangerous president in the modern history of this country.”

This unity message was echoed in his consistently friendly tone towards his primary competitors. From repeated declarations of “Joe is a friend of mine” to his reluctance to make substantive critiques of his opponents health care policies — it was Pete Buttigieg, not Sanders, who finally revealed the superficial nature of Elizabeth Warren’s plan — Sanders made it clear that he would be far lighter on his rival Democratic Party operatives than he was in 2016. Whereas his earlier campaign featured several direct attacks against Clinton, going so far as to call her “unqualified,” this version saw Sanders reiterating his belief that Biden could defeat Trump, a main conceit of the election.

Instead of suggesting a radical split within the party as, for instance, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez has occasionally done, Sanders framed the distinctions between the Democratic establishment and himself as largely friendly: “[Biden] is a decent guy, he’s just wrong on the issues.” Throughout, Sanders downplayed the anti-establishment nature of his campaign, calling off attacks, and seemingly catering to mainstream demands for unity.

This conciliatory approach became particularly apparent when it came to the question of systemic critiques of Trump, as Sanders was seemingly outflanked by the centrist Buttigieg. While “Mayor Pete” wrote an op-ed for CNN entitled “2020 election is not just about defeating Trump,” highlighting the decline of the rust belt during the Obama era, Sanders hedged any pre-2016 analysis by emphasizing Trump as a singular “demagogue” while remaining silent on the Democratic Party’s culpability in Trumps rise. Although Sanders did occasionally attack certain pre-2016 disastrous policies themselves (NAFTA) as being detrimental to US workers, he always stopped short of connecting these policies to the anti-establishment fervor which Trump’s right-wing populism was able to channel.

Though Sanders’s message of insurgency was not completely gone, it had lost significant sting; in many ways, Sanders sounded more like the conventional Democrat he was purportedly attacking.

Put alternatively, the 2020 campaign consistently painted itself as willing to play ball with the DNC, posing as a movement that shared many of the same large-scale goals, merely differing in what was practically feasible at the moment. At every turn Sanders coupled his traditional anti-establishment rhetoric — the bitter pill of universal healthcare, worker rights legislation and environmental advocacy — with the sugar of Democratic Party reconciliation, paying homage to anti-Trump rhetoric, the latest installations of Russiagate and party unity.

Instead of making distinctions between its insurgent campaign and establishment contenders, Sanders often found himself on the defensive, making the abstract case for “electability.” Seemingly concerned with not being a “true democrat,” he took pains to emphasize his pro-party record, reconciling himself even to the Obama legacy.

This strategy was also part and parcel of the campaign’s attempt to cater to the second group mentioned above: professional class left-liberals, or the so-called “high information,” college educated voter. Throughout 2020, Sanders attempted to respond to demands that his 2016 campaign was too white and sexist — centering the so-called deplorable “white working class” — by listening to the demands mainly coming from upper class liberals.

Sanders was himself reluctant to challenge dubious charges of the mythical “Bernie Bro,” whose evidence was derived from a few tweets, and broader accusations of endemic sexism in his campaign. At no point did Sanders venture a reply or attempt to contest the unsubstantiated liberal-spun narrative: for instance, pointing out that the women cited felt their complaints were “unfairly” mobilized against Sanders, or even the basic point that the working class is itself diverse and disproportionally non-white. While staffers have reported that Sanders privately “hates” identity politics, he found himself catering to its pleas for rhetorical shifts and a “politically correct” aesthetic.

Professional class demands took a toll on policy as well. Subtly lacking from the 2020 campaign was a focus on a $15 minimum wage, the loss of manufacturing jobs and big-ticket economic measures. Breaking up the big banks, a core part of Sanders’ 2016 campaign, was hardly mentioned in 2020. Instead, policies particularly attuned to middle-class concerns — tuition free college (only a third of Americans over 25 have a college degree), the relief of student loan debt, and the Green New Deal (potentially antagonistic to rural America) — took center stage. Picking up several Washington insiders such as Faiz Shakir, the former staffer of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, the radical edge of Sanders’ movement seemed to be replaced by more palatable calls for a reinvigorated PMC liberalism.

The results of this strategy were reflected in the polls. Although Sanders slightly improved with college educated voters and, at one point, polled as the best candidate to defeat Trump — purportedly voter’s main concern — he paid for these modest gains by losing large swaths of his non-traditional 2016 base. In several states with open primaries and increased voter turnout, including Virginia, Vermont and Michigan — where Sanders famously pulled off an historic upset in 2016 — he fared far worse than in his previous campaign. Sanders lost Michigan by 16 percent, Virginia by 30 percent, and while Sanders won Vermont, Biden earned enough votes to receive about a third of the state delegates. Put in stark terms, FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley found that, by April 1, Biden had won nearly 83 percent of counties that Sanders had won at that point in 2016.

Such trends also held true in states that were advantageous to Sanders in the previous election. As summarized in Angela Nagle’s and Michael Tracey’s sobering article in American Affairs:

Four years ago, [Sanders] won the Washington state caucus by a massive 46 points over Clinton. This March, he received less than 37 percent of the vote in what should have been some of his most friendly territory in the country, the Pacific Northwest, and lost the state outright to Biden. And it wasn’t a matter of suppression: voter turnout in Washington state increased by a staggering 94 percent compared to 2016. Just as the Sanders-appointed members of the commission had anticipated, large numbers of new voters were enfranchised by this administrative change — except they weren’t voting for Sanders. It was the same story in Maine. There, Sanders won the caucus in 2016 by 29 points. Having converted to a much higher-turnout primary this year, his share of the vote was cut in half, and he lost the state overall to Biden. Minnesota: same situation. Idaho: same situation.

Across the country Sanders lost support from self-identified “moderates” and “independents,” while mostly holding ground or making slight gains in professional class “very liberal” demographics. Missouri exit polls showed Biden significantly leading Sanders among men without a college degree, a group that Sanders won in 2016 by 21 percentage points. Sanders also lost support among independent voters in Missouri: around half voted for him in 2020, a drop from about 67 percent in 2016.

In other words, changes in the nature of the Sanders campaign — from an insurgent, anti-establishment disposition in 2016 to a more conciliatory approach in 2020 — were not made without significant trade-offs. These numbers indicate that adhering to the Democratic Party line not only failed to make substantial inroads with the establishment wing, but cost Sanders much of his non-traditional base. The attempt to win over the centrist and left-liberal sections of Democratic voters by focusing on Trump, obeying calls for party unity and playing nice with primary competitors saw a corresponding erosion of independents and the generally disillusioned.

Such results make logical sense as well. They bespeak a structural contradiction between the interests of the professional class or the establishment DNC and those disillusioned, regardless of party affiliation, with the system and its elites.

When voters saw Sanders catering to the former group, the result was him losing touch with the latter — visible, for instance, in his declining favorability ratings. As Glen Greenwald has noted: “there is an inherent incompatibility between saying that you’re running an insurgent race against the establishment wing of the party to bring about a revolution, while on the other hand appearing entrenched in that party and deferential to its elites.”

To say that Trump is an “existential threat” that must be defeated at all cost, for instance, runs counter to the ordinary lived reality of most Americans — whose life expectancy declined under Democrats and Republicans — and contradicts the basic conceit of revolutionary and insurgent politics: that “things as usual” are the true disaster. Suggesting that typical establishment politics are not so bad, or at least nowhere close to the threat of Trump — who was himself anti-establishment — undermines the necessity of a revolutionary movement in the first place.

Similar contradictions were operative on the flip side, with the idea that Sanders could pick up a significant chunk of establishment voters. Bluntly put, it is simply difficult to imagine that the “high-information, high-likelihood voter,” those avid readers of the New York Times, would be significantly persuaded by a “socialist” willing to play nice. The plethora of better suited traditional liberal candidates — with whom messages of unity, moderation, and deference to professionals came naturally and without the working class baggage — were always going to be better options for the middle class and the PMCs, a group for whom years of liberalism had worked well enough. Awkwardly attempting to cater to voters whose primary concerns were “defeating Trump” and Russian interference — 66 percent of DNC voters believe that Russia hacked the 2016 official vote count — Sanders stood little chance on the establishment’s home terrain.

The conciliatory strategy, in sum, fell short on both accounts. In catering to the DNC and the PMC, Sanders seemingly alienated large swaths of anti-establishment voters, making appeals to his 2016 base far less effective all the while remaining unappealing to typical Party voters. The attempt to reconcile with the Democratic establishment — walking a fine line between insurgency and palatability — ultimately worked to undermine the more radical nature of the Sanders campaign and its ability to secure, or call into existence, the mass support capable of carrying him to electoral victory.

BAD SOLIDARITY: ELIZABETH WARREN AND LEFT INSTITUTIONS

Such a diagnosis, however, must not be levied at the personal sphere alone. Although Sanders and his campaign maintain responsibility for many of the above decisions, any analysis primarily concerned with individuals is incomplete. It is necessary not simply to be attuned to personal questions, but to broader institutional concerns around Sanders and the campaign. In turning to these issues, the question of solidarity and the ability to build an effective left coalition proves central.The 2020 campaign saw a wide — and ever-widening — gap between center-liberal and left-wing solidarity. Beginning with the former, it was difficult not to notice the ability of the establishment, after some initial fumbling, to swiftly coalesce. As soon as the Sanders movement looked to be a Super-Tuesday threat, with the possibility of clinching the election, the upper class was able to organize and pressure a series of centrist candidates to drop out, pushing Biden to a previously implausible delegate majority. When establishment power was in jeopardy, the upper class keenly located its true allies, put differences aside and tactically coalesced. It had an implicit understanding of its core class interests and was able to strategically support those interests when the time came.

None of these things, as has become increasingly apparent in the 2020 campaign, could be said of the Bernie Sanders movement and the American left more broadly. The latter’s few actually existing media outlets — Jacobin, The Nation, Current Affairs, The Intercept, In These Times — struggled to come together around a set of principles, a coherent ideology, or, most directly, a single candidate — and, if they did, it was far too late.

Early on, Jacobin and Current Affairs ran pieces praising Elizabeth Warren for “making the right kind of enemies” and having “excellent ideas” as opposed to the “empty rhetoric” of many of her peers. When Warren began the race with minimal support, Doug Henwood’s Jacobin article concluded that Warren “deserves much better than she’s getting,” suggesting that Sanders and Warren work in a cooperative relation. The Nation, the self-declared “progressive” and “principled” magazine of the left, likewise lamented the “erasure of Elizabeth Warren” and asserted a necessary alliance between “the two real progressives” in the race. Both candidates, it was claimed, shared many of the same values, policies, and proposals. The task was to form a strategic alliance between an interchangeable left Sanders and a left-liberal Warren campaign against the anti-progressive center.

The Sanders movement bought into the idea of a progressive coalition as well. From as far back as 2015, Sanders saw Warren as a key political ally, reportedly offering to step aside for the prospect of her candidacy. While they both decided to run in 2020, the Sanders campaign, from its onset, explicitly refused to criticize — or even notably distinguish itself from — the Warren campaign. Throughout the primary process Sanders allied himself with Warren, denouncing some mild anti-Warren voices from his staff as “outliers,” soon to be sidelined.

This logic reached incredible heights when a low-level Sanders’ campaign memo — suggesting grass-roots organizers discuss the differences between Warren’s coalition (affluent and white) and Sanders’ (working class and diverse) — was condemned as “people saying things they shouldn’t.” In a statement released soon after the “incident,” Sanders added: “[Warren] is a friend of mine…No one is going to be attacking Elizabeth.”

Sanders’ staunch commitment to this alliance trickled down to the institutional level. Justice Democrats and Democracy for American, two progressive groups which themselves gained prominence from the 2016 Sanders movement, waited more than a year after Sanders began his campaign to endorse him, while the Working Families Party declined to endorse Sanders at all. The idea, again, popular on both institutional and movement fronts, was that Warren and Sanders represented two sides of the same progressive coin. In holding out support for one of the two candidates, one aided the movement as a whole. If one faltered, the left would coalesce around the other.

These assumptions proved gravely mistaken. As is now apparent — and was not impossible to foresee at the time — Sanders and Warren never stood in symbiotic relation, but in fact represented mutually exclusive and antagonistic positions. Warren not only actively attacked Sanders, amplifying popular center-right talking points, but detracted substantially from his base of support. As a recent article in Jacobin reported: from July 2019 to the end of February 2020, Warren lost massive amounts of her centrist supporters, while those more progressive — second choice Sanders’ voters — remained.

Even the Washington Post — an outlet built to downplay Sanders support if there was one — concluded, “the most pronounced second-choice shift in the Democratic primary field was Warren supporters going to Sanders,” and that having Warren still in the race was significantly eating into Sanders’ support:

Not only is the second-choice path for her voters more explicitly pointed at Sanders than between Klobuchar and Biden or Buttigieg and Biden, but there are more of them who could migrate. Warren averages about 15 percent in national polls — about the combined total of Buttigieg and Klobuchar. So it’s a bigger block, and it would probably be a bigger windfall for Sanders.

During the time in which Warren saw dwindling support, from late July to the early caucus period of February and March, the Warren campaign, however, dug in its heels, attacking Sanders with Clintonite accusations of sexism — many ex-Clinton staffers joined her campaign — and fabricated media stories of the “Bernie bro.”

When the crucial moment came for the left’s conciliatory work to pay off — for Warren to drop out before Super Tuesday — she, of course, did not. As if to make the point particularly clear, and after coming in an embarrassing third in her home state, Warren finally did end her campaign a few days later but declined to endorse Sanders, instead, in Nathan Robinson’s terms “choosing to perform in skits on SNL and once again publicly lambast his supporters for having sent her mean emojis on Twitter. She did not give her voters even the slightest hint that Sanders was preferable to Biden, thus implying that it didn’t matter which one won.”

In other words, the Sanders campaign — and the left more broadly — was completely undermined and caught off guard by a candidate that it itself had been bolstering for months. The left media praised Warren early and often, occasionally going so far to suggest that she was the better “progressive-left” choice than Sanders, while Sanders himself was reluctant to ever offer critique. The return on these investments, however, was less than nothing. Warren’s major role in the primary was to hold onto a base that would support Sanders, disproportionately hurting him and aiding Joe Biden.

When it finally became clear that Warren was not the candidate Sanders and much of the left thought she was — the flip-flop on Medicare for All, the embrace of status-quo foreign policy, the attacks on his campaign — it was too late. As a Buzzfeed article from early March described, the results were disastrous:

[Whereas] centrist Democrats consolidate around Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, progressive organizations that have divided in support between Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren said they do not have a plan to quickly band behind one of the two to form a coalition against the moderate threat…groups that have backed Warren for months or years — like the Working Families Party and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee — are showing no sign of relenting in their support or beginning to coalesce around Sanders’ frontrunning campaign to match the support Biden’s now receiving.

The damage was irreparable. With no chance of winning the nomination, Warren was not going to drop out and endorse a more radical left movement. Taking her liberal-centrist principles to the end, she stayed in the race through Super Tuesday knowing full-well that it would deliver a crushing blow to the Sanders campaign.

For the better unified upper class, however, this turn of events was not so hard to see coming. Aside from a few angry billionaires — which, as it were, served to give Warren needed anti-establishment credentials — traditional center-liberal figures and institutions were quite fond of Warren. Many correctly perceived her base of confused leftists and white affluent professional-class liberals as signaling a traditional liberal-technocratic campaign. Knowing that she was a “player in the game,” they were happy to have her as the “anti-establishment” establishment nominee; seeing the siphoning of Sanders’ support, they were glad to paint her and Sanders as on the same team.

Their clear perceptions and institutional discipline paid off. While the liberal center was able to coalesce and identify its potential allies fairly early on, the left and the Sanders movement was not. It spent part of its limited institutional resources propping up a professional class liberal candidate with interests antagonistic to its own. When the time came to realize its mistake, the game was over: Warren had already coalesced a fair amount of left support and the Sanders movement could not pressure her to act, likely against her will, with the interest of the working class.

Sanders and corresponding institutions, put another way, lacked both the diagnostic tools necessary to discern a candidate antagonistic to its interest and the institutional ad hoc solidarity to recover from its mistakes. The question arises: If it took one year to discern that a candidate claiming to be “capitalist to my bones” was not good for the left, then what will happen when a far more insidious upper class movement comes along?

Such a problem thus extends far beyond Warren, who is the most recent manifestation of it, to the problem of institutional struggle more broadly. It bespeaks a larger lacuna in left solidarity and in its ability to stay unified along principled lines. There was, to be clear, no error on Warren’s part — her actions reflect her politics — but a basic breakdown of solidarity within the Sanders movement and the left itself.

WHAT IS TO BE LEARNED?

What, then, does all this mean going forward?There is bad news and there is good news. While, of course, signs of the left’s strategic shortcomings, institutional decay and lack of principled organization are deeply worrying, they are also not immutable. It is, in fact, possible to have good strategy and principled organization, characteristics often demonstrated by the ruling class, but in revolutionary form.

The devil, however, is in the details. A reinvigorated left, first and foremost, requires the willingness to look itself in the mirror; it cannot learn from its mistakes if it refuses to admit that it made any. Rather than remaining drunk on a cheap optimism — “we’re winning, we’re winning, we were robbed!” — one that sees every defeat as victory by another means, it needs a grounded materialist analysis of its failures and how they may be overcome. Instead of celebrating shifts in the mythical Overton window, rigorous analysis calls for a confrontation with the fact that gains in the supposed “battle of ideas” are not enough.

In this spirit, it has been remarked that for politics an obituary is always an autopsy. Any political diagnosis is also linked to a more normative analysis of what could have been done differently. In line with such sentiments, then, and as an effort to avoid “keeping one’s hands clean,” a few corresponding lessons, entailed by the above analysis, can now be proposed:

1. A Different Left Base

Given the historic alliance between the Democratic Party and organized labor, as well as its post-war positions on social issues, the inchoate left has often perceived the Party as a site for institutional struggle. Although the Democratic establishment shifted rightward in the neoliberal period, the prospect of capturing its liberal base to form a “progressive wing” of the Party remained.

Recent years, however, have witnessed critical shifts in the class compositions of the electoral landscape. In the wake of the 2018 midterm elections, the Democratic Party currently holds 41 of the top 50 wealthiest Congressional districts — including all of the top 10 — while the Republican Party controls a majority of lower-income rural counties. The partisan divide in education levels, a key indicator of class, has reversed: non-college educated voters, especially white voters, have trended Republican, while college-educated voters of all races lean Democratic.

These shifts were not inadvertent, but reflective of the DNC’s consciously promoted aims; as Chuck Schumer explained in a particularly honest statement on his party’s strategy for the future: “For every blue collar Democrat we will lose in Western [Pennsylvania], we will pick up two, three moderate Republicans in the suburbs of Philadelphia.” Even today, with Covid-19 producing an ever-widening wealth gap, Rahm Emanuel has called for “Biden Republicans,” the mirror image of Reagan Democrats. The task, he stated, is simply to “culturally move them [elite, economically conservative voters] into a comfort zone” within the Democratic Party.

To some, this is evidence that the Sanders 2020 campaign was “structurally” impossible. That is, since the Democratic base had shifted rightward — and Sanders was beholden to that base — Sanders had to shift rightward as well, leaving no choice but to lob hopeless appeals to professional and establishment liberals. By this logic, Sanders’ decision to run on a Democratic Party ticket, one increasingly dominated by upper-class interests, doomed any prospects for a radical campaign before it even began.

While this point has some merit, there is, however, a third option: base building. Instead of tailing changing voter demographics, Sanders could have — and future left movement still can — built (build) a new base, one that turns to the notion of class solidarity. The left, in other words, may stand between impossibility and capitulation. Rather than withdrawing from the electoral sphere entirely, often referred to as “ultra-leftism,” or capitulating to professional class demands, the task would be to actively cultivate an insurgent voting bloc composed of the working poor, independents, non-voters and lumpenproletariat.

This is not to say that the left could not run Democratic, or even consist of some professional-class people, but simply that it would strive to do what Sanders himself claimed to accomplish: build an authentically insurgent campaign. Such a movement would not be grounded in party unity, for instance, but be willing — like the elites working against Sanders — to cause significant “party damage.” The task would not be winning concessions or catering to “the lesser of two evils” but unapologetically building a non-partisan base required for a revolutionary movement; if this destabilized the DNC in the process, the movement would say, then so be it.

2. Willingness to Take Risks

The second point dovetails off the first. The Sanders campaign displayed remarkable conservatism in its efforts to placate the DNC, consistently heeding the Democratic establishment’s narratives — recall: its stance towards Trump, Russiagate, and party unity. However, a politics which seeks to galvanize the disillusioned, or those precisely whom conventional political strategy cannot reach, must be unafraid to reject conventional political wisdom.

To take an example from the right-populist playbook, Trump’s 2016 Republican campaign succeeded precisely by rejecting standard electoral dogma through “anti-establishment” rhetoric. From the personal — vulgar attacks on his opponents and overt appeals to national pathos — to the political — criticisms of free trade, perpetual war and post-industrial economic decline — there were few taboos Trump was unwilling to break. While this ultimately amounted to a largely aesthetic outsider status — Trump, Twitter aside, behaves as an ordinary neoliberal Republican — a left-wing version would seek to provide content to a new anti-establishment form.

Cognizance of the dynamics of class conflict could guide the left to think outside the box: defying advice from liberal “experts,” spurning the tyranny of the polls and bucking many bi-partisan prohibitions. While, of course, such a risky left would not embrace nationalist sentiments or revert to jingoistic scapegoating, it would certainly go after many establishment taboos: the objectivity of the media, the necessity of “pragmatic” compromise, and the importance of party politics, to start. In so doing, the point would not be to needlessly antagonize traditional politics, but to both create the necessary space for a more radical political imagination and the mass appeal required to enact such a vision.

That is, an insurgent campaign would benefit from both broadening political horizons — a 2019 Vox article, for instance, noted how declaring a “national emergency” could be key for passing left-wing environmental policies — and galvanizing those majorities disillusioned with the status quo, coupling outsider politics with outsider style.

3. Movement First Politics

A large segment of the Sanders’ 2020 movement came from working class and lower-income people. Yet when the time came to fight for these groups — who disproportionately donated to his record-breaking fund-raising campaign — Sanders often chose to protect the interests of the DNC. This was not only reflected in the silencing of more radical dissent, coming to fruition in verboten critiques of Warren and Biden, but post-electoral decisions to “play by the rules,” visible even today in his reluctance to organize COVID-related actions such as a rent strike. In each case, Sanders offered nominal support to the movement when convenient but stopped short of making any substantial commitments.

Perhaps the central tenet of a “risky left” politics, however, is its willingness to embrace and empower the movement behind it. As Sanders himself often acknowledged, left wing electoral endeavors depend upon a struggle from below, not only to carry them to victory, but to power their agenda through the throes of the establishment; he hoped to be, in his words, an “organizer in chief.”

The task, then, for a prospective left, would be to stick to Sanders’ words more than Sanders himself: to risk empowering a left revolutionary base, even if — or perhaps because — it risks antagonizing standard liberal and conservative forces. Such a movement would stand in a reciprocal relation with those below it. Rather than only offering them conditional support, it would gamble on empowering — and receiving power from — a mass disillusioned base, channeling and directing this energy towards revolutionary ends.

4. Left but Not Woke

Throughout his 2020 campaign Sanders catered to the demands of professional, so-called “woke” demographics. Many of his policies and aesthetics shifted from a “problematic” 2016 version to a more PMC friendly 2020 instantiation — for instance, dropping much of the so-called “populist” platform that criticized free trade, big banks and spoke to a declining manufacturing sector.

Yet the issues with such a capitulation were multiple: not only did the PMC make up a small percentage of the population — despite being influential in online discourses and having large sway in the general media narrative, it fundamentally lacked the numbers for a large-scale electoral left movement — but its interest and aesthetic preferences were often antagonistic to a more traditional lower class left base.

Reflected in empirical terms (polling data) and theoretical terms (conflicting material concerns between the manufacturing and professional economies) there were — and are — irreconcilable antagonisms between the two groups. One is fundamentally oriented towards the establishment — it aims to join and reform it — while the other is opposed, presenting the base for the establishment itself to be uprooted.

In order to overcome these difficulties, then, a future left movement would have to side with the latter (point 1) over the former. It would have to risk provocation, or not being “woke” enough for an elite liberal establishment and unashamedly embrace a lower-class movement. Rather than keeping up with the latest trends in upper-class liberal aesthetics, it would cater itself to a different segment of the population entirely. As attacks and slanders inevitably emerge from the media, it would be unafraid to spurn the backlash and malign the corporate and PMC press, knowing that the voices of opposition do not necessarily reflect the base it is catering towards. If, for instance, polls show that only two percent of the Hispanic population would use the term “Latinx” to describe their ethnicity, it would think-twice about adopting it — or shaming those who do not — to placate the PMC.

While this, of course, is not to suggest that cultural questions of discrimination such as racism, sexism and xenophobia should be taken lightly, it is to say that they are only addressed by a movement not led by — or catered to — the professional class. Only a majoritarian left rooted in those who stand to benefit the most from its proposals — the lower classes — could generate the support and power necessary for economic and social change.

5. (Lumpen)Proletarian Solidarity

In 2020, left institutions proved unable to delineate between social-political movements which supported upper class interests and those that did not. Perhaps best exemplified in the stance the left took towards Elizabeth Warren, it routinely conflated PMC and lower-class positions. Unable to distinguish between the two antagonistic groups, Sanders and many left institutions acted in a way that catalyzed their own undoing, generating disorganization within the left and wasting its limited resources.

A corrective of these mistakes would require a better understanding of the left’s role in politics, where the possibilities of change come from, and those who share its interests. A better organized left movement, in other words, could distinguish between its enemies — the differences that make a difference — and its friends — the differences that do not. To the former, solidarity entails fierce and strategic opposition; to the latter it requires reconciliation, coordination and understanding.

Stated positively, solidarity requires criteria. Yet such criteria could neither be a moral purity test — one that along PMC lines may ex-communicate “bad” people — nor a supposedly “strategic” capitulation that, under the guise of tactic, caters to the DNC. Instead, it would be primarily attuned to coalescing lower-class power. X is in solidarity with the left if X bolsters the material interest and power of the dispossessed classes, fighting the same core struggles, though, perhaps in different domains, that are at the core of a multitude of different symptoms.

This is not only because the working and lumpen classes are most likely to support a revolutionary movement as it aligns with their material self-interest, but because they contain the power and numbers capable of enacting the radical change aspired to. As such, when a person, institution or movement sacrifices these struggles for separate concerns, when they attempt to forge ally-ship with liberal-progressive or middle-class causes, they undercut the movement as such and the “radical changes” they purport to seek. Bearing this in mind, a successful future left movement would confront the antagonistic relationship between middle and lower class politics and risk unconditionally siding with the latter.

THE SPECTER OF SUCCESS

The question of parliamentary politics can be defined as taking up two related yet distinct goals: the winning of electoral power and the advancement of an authentic left movement. While it may be entirely possible to achieve the former without the latter, a genuinely insurgent electoral strategy must aim for both.

Although the Sanders campaign ultimately fell short on each account — even a victory, gained without a more radical base would likely mean electoral setback — his failures, however, were not total. The left’s striving for electoral power offers an instructive experience: demonstrating not only how power reacts when threatened but also the possibility for things to go otherwise.

Failure, in other words, makes visible the specter of success. Learning what happens when the left attempts to build a coalition with establishment and professional forces, what happens when it caters to party politics and what happens when it lacks institutional solidarity is invaluable to future insurgent movements.

The task then is not to celebrate these shortcomings, nor to cast them as inevitable, but to pick up where Sanders left off: to subtract Sander’s deference to elites, concretize his movement-oriented philosophy and to add a more militant commitment to a revolutionary base necessary to break out of the contemporary cycle of left defeat.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/reflections-sanders-2020-2/