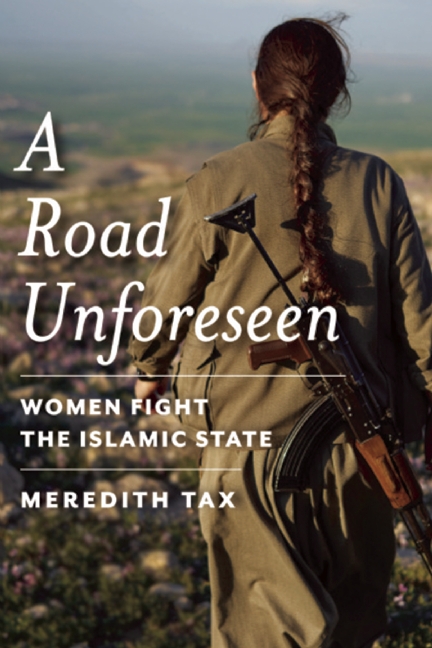

Photo: Kurdishstruggle

Review: A Road Unforeseen — Women Fight the Islamic State

- August 15, 2016

Gender & Governmentality

“Any movement for real transformation must make the demands of women central,” argues Meredith Tax in her superb book on the Kurdish women’s struggle.

- Author

Second Wave feminism, once it erupted in the late 1960s, called out misogyny where it came into view. Breathtakingly, it insisted on recognizing human rights for all women everywhere. But today many Western feminists hesitate to speak in such bold terms. Wrestling with the legacy of imperialism, they decline to pass judgment on the sexist behavior of local men in postcolonial societies. As a result, the moral compass on human rights for women has weakened.

This retreat occurs even in the face of the brutally misogynistic Islamic State group (ISIS). To be sure, ISIS tortures and beheads people regardless of gender; it has slaughtered and abducted thousands of civilians, male and female; it has committed systematic genocide against Yazidis, both men and women.

But the salafi-jihadists of the would-be caliphate reserve especially cruel treatment for women, subjecting them to organized rape and systematic sexual slavery, including young girls. Their standard operating procedure is to buy and sell females, gang-rape them, and enslave them. A year or so ago, the liberal feminist Phyllis Chesler called out Western feminists for their silence in the face of ISIS’ murderous misogyny.

The socialist Meredith Tax, who like Chesler has origins in the Second Wave, has been speaking out on behalf women’s human rights internationally for decades. She has worked unwaveringly to bring attention to honor killings, coerced and childhood marriage, domestic violence, and rape, as well female genital mutilation.

Since 1995 she has headed Women’s WORLD, a global free speech network of feminist writers that opposes the silencing of women’s voices. In her previous book, The Double Bind (2013), she criticized both right-wing fundamentalism and the Western leftists who soft-pedaled and relativized its abuses.

Separating the sexes: rise of the Islamic State

With her combined expertise on fundamentalism, feminism, and human rights, Tax was not one to hold back when ISIS overran Mount Sinjar and tried to drive out the non-Islamic Yazidis who have lived there peacefully for millennia. In her new book, A Road Unforeseen, she shows what it means to view aspects of the Middle East through these basic prisms.

Fundamentalist movements, she explains, operationally look backward to an allegedly more benign past and identify women as “the symbol and carriers of a ‘pure’ national, ethnic, or religious identity.” To ensure that purity, male control over their behavior becomes imperative, and once such movements go to war with their neighbors, “rape is the weapon by which they demonstrate their victory over ‘the other,’ by defiling ‘his’ women and making them give birth to enemy aliens.”

In a detailed discussion of the rise of Islamic State, Tax highlights a Daesh manifesto that insists on essential differences between the sexes: “If roles are mixed and positions overlap, humanity is thrown into a state of flux and instability. The base of society is shaken, its foundations crumble and its walls collapse.” Women must therefore be confined the domestic sphere.

So women who have lived under Daesh rule, Tax explains, “were unable to move freely; they could not go outside without a male relative; their education was strictly limited; they had to wear three veils over their faces and would be lashed if their eyes could be seen; and they could be stoned to death if they were accused of adultery.”

This was the system Daesh had in mind for the Yazidi women, not to mention the mass murder of the men and the brainwashing of boys. Fleeing this terror, thousands of Yazidis were stranded on Sinjar Mountain in August 2014. The forces who came to their rescue represented the antithesis of Daesh: the gender-equal units of the PKK (internationally stigmatized by governments that pander to the persecutor of the Turkish Kurds: the Turkish state) and of the YPG/YPJ, of the liberated cantons of northern Syria known as Rojava.

In these forces, men and women fight together to powerful effect, such that, “without heavy weapons or air cover, [they] cut a path of roughly 100 kilometers through the mountains to Cizire canton, battling Daesh all the way. On August 10 they got the last of the Yazidis out and were able to report that they had brought an estimate 100,000 refugees to safety.”

Women in the Kurdish freedom struggle

The forces that carried out this spectacular rescue mostly emerged from the Kurdish freedom movement, whose history Tax recounts by drawing on a wide array of English-language sources and synthesizing them, lacing her narrative with illuminating insights and surprising details. In twentieth-century Turkey the “implacable Kemalism” that for generations harshly suppressed Kurdish strivings for identity and culture led to the founding of the PKK in 1978.

Tax takes us to its training grounds for armed struggle in the Bekaa Valley, then into its war with the Turkish state starting in 1984. She traces the PKK’s history through its congresses, explaining its ideological training, the role of criticism and self-criticism. Overtones of Paolo Freire’s “critical pedagogy,” or participatory education, enter into the discussion. Her tale is cautionary as well as supportive, laying out the organization’s troubled past, complete with splits and concerns for individuality and “the high value put on self-abnegation.”

The early 1990s saw the rise political parties focusing on Kurdish issues and a momentous uprising that began in Nusaybin. Tax details the roles of two notable women, the parliamentarian Leyla Zana and the revolutionary Sakine Cansiz, both of whom served protracted periods of time in Turkish prisons. Meanwhile Turkey’s “deep state” trained forces at the CIA’s notorious School of the Americas, who then went on to raze thousands of Kurdish villages and bomb the Qandil Mountains, where the PKK are based.

“Such a strategy requires complete ruthlessness towards civilians,” Tax points out, which the Turkish state was willing to exercise to “stamp out every sign of resistance.” Yet it failed to achieve this patently impossible goal. “By this time,” she writes, “the futility of seeking a purely military solution to a political problem should have been evident to the Turkish government.”

Twenty-five dismal years later the futility is evident to everyone paying attention, except the Turkish state itself. Indeed, to read Tax’s history of the Turkish-Kurdish conflict is to experience a repeating loop that changes only in nightmarishness. The 1990s razing of villages in the southeast recurs today in the destruction of Kurdish cities. In the 1990s the Turkish state stripped members a pro-Kurdish party (HEP) of their parliamentary immunity, much as in the spring of 2016 it stripped members of the current pro-Kurdish party, the HDP, of their immunity. Repeated calls for peace and ceasefires from the Kurdish side, then as now, go ignored.

The autonomous women’s army of the PKK

In the illuminating chapter “Kurdish Women Rising,” Tax addresses the way the women’s revolution in Rojava has “put women’s liberation so squarely at the center of its revolutionary project.” She brings to the table decades of experience in the international women’s movement as well as the left. Often in Western women’s peace movements, she notes, feminist critiques of war and militarism cast women as intrinsically peace-loving and nonviolent and harmonious compared to men. Gloria Steinem voiced a common theme when she praised women’s “special ability to make connections between people” over masculine tendencies to display aggression.

Such thinking is alien to the women of the PKK and of the YPG/YPJ. As one female Iraqi Kurdish activist responds: “Exactly who are [women] supposed to be making peace with? With ISIS?” Kurdish women fight back. PKK women created their first women’s organization in 1987. By 1993 one-third of new PKK recruits were women, Tax tells us; by 1997, 5,000 women were fighting in the PKK’s separate women’s militias and 11,000 more were in mixed units.

Tax analyzes the female guerrillas of the PKK in the light of those in mixed units in other post-World War II liberation struggles: women fought in the ranks of armed movements in China, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, in Angola and Eritrea and Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe; and in Cuba, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Chiapas. But in these struggles, she notes, the deployment of women was usually a matter of numbers: “many national liberation struggles sought to enlist women in combat mainly because they needed more soldiers.”

By contrast, the PKK built its autonomous women’s army “not to increase the number of fighters but to actually strengthen women cadre and change the consciousness of both sexes.” Moreover, in those other struggles women fighters “rarely achieved leadership roles or led male troops.” But in the PKK, even in the 1990s, “some mixed units had women commanders as well.”

Nor, in other liberation struggles, did participation in guerrilla forces have ramifications beyond the military: “the empowerment of women has so seldom been a priority for movements engaged in armed struggle.” The Sandinistas in Nicaragua, for example, pursued women-friendly policies “principally because they fulfilled some wider goal or goals, whether these were social welfare, development, social equality, or political mobilization in defense of the revolution.”

Post-revolutionary male leaders, Tax notes, “have seldom wanted to change their own behavior or share the sources of real power.” The Maoists of China propagated the slogan that “women hold up half the sky,” but revolutions grounded in Marxism, notes Tax, “have — at best — seen women as support troops for the working class, not as a submerged and dominated majority whose liberation is fundamental to everyone else’s.”

In the Kurdish movement, by contrast, the battle for women’s rights and autonomy is essential to the struggle — and serves as the basis for reorganizing gender relations in the society as a whole. In the PKK the formation of women’s units functioned as “a first step in forming autonomous women’s organizations that would parallel all the other structures of the PKK.” In 1995 the PKK formally resolved: “In all sectors of the economy, all social institutions, and even in the realm of culture, organizations will be created and modeled after this army.” The PKK’s uniqueness, says Tax, “lay in seeing the transformation of gender relations not as a sidebar to nationalist revolution but as the central task that would determine the success or failure of the whole endeavor.”

A movement for real transformation

There is another way in which the Kurdish movement is unusual among international women’s movements: it makes celibacy mandatory. Sexual relationships are forbidden to guerrillas and to PKK leadership, initially to enable the recruitment of women from families concerned about “honor.”

Women’s movements elsewhere, while critiquing power relations within marriage, have sought to re-create intimate relations and childrearing along more liberatory lines: free love; redefined family units; communitarian solutions. But marriage is still the way many people seek intimacy and companionship and that societies “ensure sexual access and unpaid reproductive labor.”

Other women’s movements place central emphasis on reproductive freedom, on women being able to decide for themselves whether to bear children, and when, and how many. It’s possible to view mandatory desexualization, she pauses to observe, as a new restriction on women. To which the PKK would respond that in its ranks individual fulfillment comes not through personal relationships but by giving oneself to the struggle. Militants dedicated to resistance, indeed, undergo a re-creation of personality, attempting to eradicate intolerance, domination, and aggression. For the sake of Kurdish freedom, they choose to live with personal sacrifice, not just celibacy but separation from family and former friends, and renunciation of alcohol and tobacco.

Such sacrifices are considered necessary, Tax explains, “in order to become new men and free women — fully-developed human beings who had left behind all traces of feudal and tribal personality and had thus becoming capable of transforming Kurdistan.”

Tax recounts the PKK’s paradigm shift during the 1990s and early 2000s, rejecting the goal of a separate Kurdish nation-state in favor of democratic confederalism, a program for bottom-up democracy, gender equality, ecology, and cooperative economy.

She leads us into northern Syria and the implementation of democratic confederalism in a series of councils and assemblies, where leadership is dual and the gender quorum for all meetings. Curiously, she explores the role of TEV-DEM and the PYD, placing accusations of human rights violations in the context of anti-Rojava agendas. The broad affirmation of human rights in the Social Contract of January 2014 seems a crowning achievement, one we can hope will one day be extended to all of Syria.

Her book covers much else besides: the tribal politics of Iraqi Kurdistan, from the emergence of the KDP under the elder Barzani to the stressed nepotism and corruption of the KRG today. Another chapter is devoted to Turkey, where the increasingly authoritarian AKP government is moving ever closer to its own brand of fundamentalism that, once again, aims to confine women to the domestic sphere. Meanwhile the pro-Kurdish HDP party calls for the emancipation of women and democratic autonomy in Turkey along the lines of Rojava.

Tax’s book is a welcome addition to the growing literature in English on the Kurds and will be mined for its perspectives and insights for years to come. “Any movement for real transformation,” she insists, “must make the demands of women central.” This superb book will be an essential resource for this question in the years to come.

A Road Unforeseen by Meredith Tax will be published on August 23, 2016.

Order your copy here.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/review-road-unforeseen-women-fight-islamic-state/