The revolutionary challenge of “the long 1968”

- January 5, 2019

People & Protest

The struggles of 1968 remade the landscape of social movements and popular resistance for decades to come. What do these struggles have to tell us today?

- Author

In revolutionary moments, social realities that are hard to see in calmer periods rise to the surface as they are threatened, crumble, forced to recombine in new ways. In the “long 1968” — the cycle of struggles that shook the Global North from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s — what had seemed like a stable postwar order, backed by superpower might and economically promising in its many variants, from Western welfare states, Eastern state socialism to Southern national-developmentalism, turned out to be anything but.

The French government wavered and was nearly toppled by what at the time was the largest general strike in world history. Czechoslovakia, perhaps the Soviet bloc state with greatest popular support, shifted towards radical transformation, only to be met by the tanks of the Warsaw Pact. In Derry and Mexico City, student radicals challenging the post-colonial order were met with state violence. In the US, the cycle that began with the Civil Rights movement was reaching its height in 1968, while Italy’s years of struggle were only starting. Social movements were on the rise across West Germany and Japan, Canada and Denmark, Yugoslavia and Great Britain, marking a massive shift in popular struggle and culture. For a few years, the beach of alternative possible worlds was glimpsed beneath the paving stones of a dull postwar conservatism.

These struggles remade the landscape of social movements and popular resistance for decades to come: Autonomia and Situationism, a rainbow of feminisms, anarchism and Trotskyism, Black and indigenous activism, counter-cultural and lesbian/gay movements offered new ways of thinking grounded in radical struggle. Beyond this, the moment in which social relationships were laid bare and it was possible to imagine a world beyond capitalism, patriarchy and the racial global order still resonates today as an experience of revolutionary possibility.

Lessons for struggle today

What, if anything, do the struggles of 1968 have to tell us today? Many attempts at identifying the “lessons” of the long 1968 are circular: they select the elements of the movements of those years that feel most attractive to the writer and use those elements to argue that their own line is correct and their opponents wrong-headed. History, after all, is written in the present: even when — as sometimes still happens for 1968 — it is written by those who were involved, their politics today are not those they had at the time.

Nineteen-sixty-eight — like most past revolutionary experiences — also has a double aspect. On the one hand, it represents a moment of mass mobilization: this is why we still talk about it. On the other hand, it was only partially successful, and not necessarily in ways participants would recognize. This too is why we still talk about it, because we are not commemorating our past victories but trying to work out how we can win next time. So identifying something with “1968” does not make it a guaranteed, authentic route to making a successful revolution. Nor, for that matter, does it make it automatically wrong: the forces arrayed against the movements of that year included two superpowers and economic systems then at the height of their powers, so we should not assume that a better “line” would have solved everything.

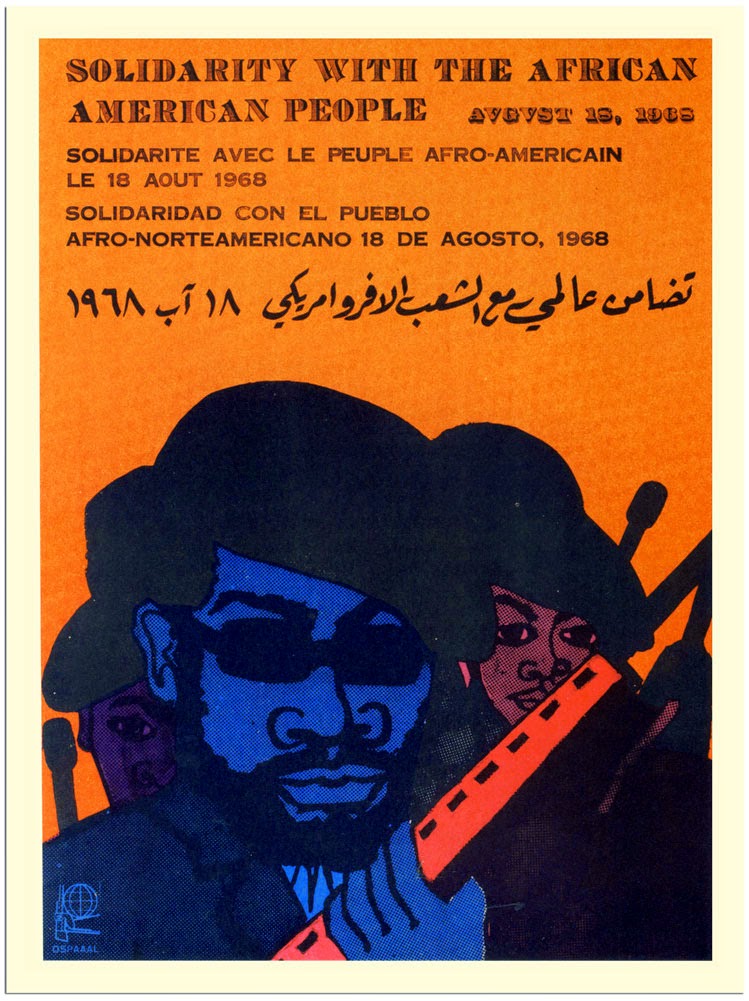

Poster by OSPAAAL, the Cuban Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

A better approach is to contrast 1968 to other revolutionary experiences, and to less massive social movements before and after. If we do this, we can start to see something more fundamental. Revolutionary moments like 1968 see the large-scale mobilization of many different sectors of society. Among groups like industrial workers where there were already substantial, organized struggles, new groups — first-generation factory workers, migrant workers, young workers, women workers — come to the fore, highlighting new issues and different ways of struggling. In other cases — students, ethnic minorities, women, lesbian and gay people — there is a revival of struggle among parts of the population who had been previously inactive, resigned or demobilized after earlier defeats. We also see struggles erupting on issues which had been off the political agenda for decades, notably around power relations within political organizations, the politics of education, everyday culture, consumerism, sexual and interpersonal relations, the role of art and the politics of consciousness — all issues which were vibrant in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but increasingly squeezed out from the 1930s to the 1950s.

The many voices of 1968

Revolutions, in other words, involve the articulation of new voices and voices which had been silenced, saying both new things and things which had not been said effectively for decades. This is fundamental to the experience of revolution: the mobilization of new sectors and of new groups within already politicized sectors, as well as the questioning of what people had previously been resigned to. “Mass participation,” fundamental to revolution, means precisely this. But then, because these groups are so different and are working their way towards a voice of their own, they say many different things that are not immediately or obviously identical with one another.

Our new book, Voices of 1968, makes this visible in fascinating, often hilarious and sometimes tragic ways. We decided to focus entirely on what activists actually said at the time on posters and in flyers, in graffiti and songs, in manifestos and strategizing, reports from actions and personal stories, black humor and spoofs. Across twelve different countries we tracked many different movements: student and worker struggles; lesbian/gay and feminist activism; migrant, ethnic minority and indigenous voices; hippies and guerrillas; anti-war and left movements; solidarity and environmentalism spoke in their own voices.

We hear from underground resistance to the invasion of Czechoslovakia, black feminist strategy in Britain, the start of guerrilla struggle in southeast Mexico, Black Panthers meeting radical southern whites, the occupation of Denmark’s Christiania, the birth of Japanese environmentalism, a Moroccan Maoist in France, the Yugoslav student uprising, radical anti-consumerism in West Germany, Red Power demands in Canada, Irish republicans discussing the possibilities of “Free Derry” and the rise of the Red Brigades in Italy. These voices are diverse, dramatic, smart and witty — anything but homogeneous.

Any real revolution, today, will look like this. And this means that one of the tasks of revolutionaries in the present is to engage with this reality. This runs counter to most forms of sectarian learning, as it does to other forces shaping much of the radical left: the niche markets of intellectual commodities within which people come to identify and consume as anarchists, feminists, Marxists, autonomists, anti-racists and so on; and the equally specialized structures of radical academia. The ways in which the “means of intellectual production” and distribution are organized shapes our understanding and pushes towards constructing narrowly-defined identities around ideas: this does not help us when new voices and movements emerge.

Revolutionary praxis involves learning to listen to these new voices, without automatically comparing them to the sets of ideas we have invested in and finding them — inevitably — wanting, but also without taking emergent expressions of social realities in struggle as complete accounts of what is going on and what those groups want. We listen with respect, but with an awareness that these voices and groups are also in movement, developing their own understandings. So we enter into conversation, trying to hold our own ideas lightly and expecting the same of others.

Connecting across diversity

This points to a second challenge, which we can hear again and again in the voices of 1968: the need to make connections, not least in the face of a violent state which seeks simply to repress these processes of emergence because it — rightly — perceives them as threatening the existing order. In the long 1968, movements sought to make connections across state boundaries, across the Iron Curtain between East and West, and between the Global South and the Global North — most obviously, in opposition to the Vietnam War, which played a comparable role to today’s wars in the Middle East. They sought to make connections between different issues and, as with many women’s movements, to break out of the constraining structures of earlier movements. They sought to take other movements further, construct possible futures together — or come together to defeat the paid thugs in uniform who appear, East and West, again and again in accounts of those years.

Comparing 1968 with other revolutionary upsurges shows us that the diversity of voices that make up any actual revolution was always a challenge. There is no golden revolutionary past in which people started out unified and agreeing with one another. Anarchists, Trotskyists and Stalinists in the Spanish Civil War; Lenin vs Alexandra Kollontai on gender and sexuality; reformists vs revolutionaries at the end of the Kaiserreich; socialists vs bourgeois nationalists in Ireland’s Easter Rising; radical democrats, conservatives and communists in the European Resistance — dissension and conflict is an inevitable part of revolution, reflecting the actual complexities not just of the old society but also of the process of coming to speak and organize independently.

Even by these standards 1968 appears as particularly diverse and the challenge of making connections particularly difficult. In the long 1968 the practice of working together survived better, and for longer, in the urban and rural counter-cultures that lasted well into the 1970s and that served as bases for many new movements than did any shared idea: an important materialist point. It was only when a resurgent neoliberalism managed to buy off upwardly-mobile parts of some of the new movements — green consumerism, the pink pound, boardroom feminism, and so on — and when academia and the (actual) marketplace of ideas came to substitute for learning in struggle as the main source for activists’ thinking that theoretical disagreements came to represent the new disaggregation of struggle.

In 1968, the diversity of ideas was particularly visible because of the collapse of older ways of homogenizing struggles. Social democracy and Stalinism, American liberalism and conservative Irish or Mexican nationalism alike had previously managed to exert a significant hegemony over most expressions of dissent, with movements routinely focused on gaining a hearing within established political parties, often those with regular access to state power. This homogeneity had come at a cost: at the expense of women and LGBT+ people, of migrants and ethnic minorities, and of more radical demands around labor, state power and international relations. It had always been an exclusionary homogeneity, meaning that once these groups found a voice of their own it would struggle to remain relevant. The rapid decline of Stalinism after 1968, and the slower but equally inexorable collapse of social democracy, underline this process.

So there can be no revolutionary future, as the “nostalgic left” sometimes imagines, in trying to go back to some past golden age without diversity, where everyone was willing to line up behind a single banner for lack of any alternative. The second “lesson of 1968,” then, is that effective organizing needs to start by taking each other seriously: not by constructing some artificial unity in a small circle and then getting upset when reality refuses to respond, but rather by recognizing which struggles, “from below and to the left,” actually exist and how they express and organize themselves, and then trying to work from that, to find shared points of alliance.

To give an example that the nostalgic left should recognize: in the 1860s groups of migrant Irish workers in London regularly fought with groups of English radical workers. The Irish were committed to Catholicism as (in their minds) an expression of anti-colonialism and community identity, and hence supported the Pope, besieged in Rome, against the process of Italian unification. However English radicals had often identified with Italian nationalism, at least in the liberal and Romantic form represented by Garibaldi: its exiles were very present in pre-1860 London and Paris, and opposition to the Habsburgs and Bourbons made sense to any European radical — to say nothing of hostility to a papacy which had opposed the French Revolution, 1848 and every new development in ideas and politics.

This conflict was resolved in part when the Franco-Prussian war led to the withdrawal of French troops from Rome and its incorporation into the new Italian state; but more importantly when Irish migrant workers and English radical workers formed new alliances against imperialism, in opposition to repression in Ireland and imperial adventures in the Sudan and elsewhere. Activists had no effect on the former, but the new alliance had to be actively made, as did “the working class” as a political agent — as E.P. Thompson famously pointed out. Unity-in-diversity is an achievement of shared struggle.

The movements of 1968 consistently sought to find ways of working together: news from other countries and other movements, national and international congresses, practical solidarity and joint demonstrations were regular features of the period. Their success was unsurprisingly uneven: in most cases they did not have enough time to learn together and form alliances, because the new voices had only come to speak during the revolutionary upsurge itself. Today the situation is different: we have the chance to listen to each other and to form alliances before the next moment of mass mobilization and to work out beforehand what the issues are that we can agree on and work together around.

What can we learn from 1968?

There are good reasons why radicals read the history of past revolutions. Actual revolutions happen so fast, and on such a scale, that anything that can be learnt from the past in periods of relative quiet — when only a fraction of the population is on the streets — is worth learning and reflecting on then. The actual experience of revolutions is not only exhilarating, it is also exhausting and comes at great cost in terms of people’s lives.

And a revolution is not simply the scaling-up of today’s struggles; the sudden involvement of vast numbers of previously inactive people, the trembling or collapsing of previously-stable power structures, the moments of total possibility and the scale on which the opposition mobilize are all qualitatively different to our normal experience. At the height of big movement waves, we can start to glimpse something of this, but if we want to be able to act in such situations, the more we can think forward into these “weeks when decades happen,” the better.

Along with thinking forwards, revolutionary praxis can also start to organize forwards. This means creating organizations able to listen to and learn from the emergence of new movements as well as entering into genuine dialogue with existing ones. It means learning to organize on the basis of a recognition that people’s lives are radically different, that they have to develop their own understanding and ways of acting, but that this is not a closed space but a space of process: we try to meet people where they are, but then invite them to go on a journey with us whose route and goal we work out together.

In practice, this means building alliances particularly with those activists who want to go further, who see the broader implications of their specific challenge to structures of power, exploitation and cultural hierarchy, as against those who want to tweak the existing order in ways that include them. This has to be done through common action — spaces of discussion, joint campaigns, projects for a different world — bringing together many different voices, movements, emergent struggles, experiences in a three-dimensional space that doesn’t seek to flatten everything behind a single line, recognizes the specificity and importance of each different struggle but tries to find what is common: “one no, many yeses” as the Zapatistas put it.

Neoliberalism, as Alf Nilsen and I wrote a few years ago, is already in its twilight; the real question is whether the new right will be able to build stable alliances to enshrine a new barbarism as the dominant social form for decades to come, or whether our movements will be able to connect with the many different forms of popular discontent to help that other world which Arundhati Roy famously said she could hear breathing to survive, grow and thrive. We do not have very much time left to learn how to do this.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/revolutionary-challenge-long-1968/