The rise of revolutionary street art in Oaxaca

- October 3, 2014

City & Commons

For years, the walls of Oaxaca have been a canvas for expressions of social anger. Now the revolutionary role of local artists is finally recognized.

- Author

Mexico has a long history of revolutionary art. Especially well-known are the revolution-era muralists from the early 20th century, such as Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros. These artists painted masterpieces in public spaces, aiming to create a “public and accessible visual dialogue with the Mexican people.”

Today, in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, a new street art phenomenon has taken root. When walking around Oaxaca City, the quality of art that can be found in the streets is striking. More than just beautifying these spaces, many of the pieces provide pointed sociopolitical commentary. They remind passers-by of some of the worst problems Oaxaca, and Mexico more generally, are facing right now — political repression, grinding poverty, the perils of migration, threats to Indigenous people and environmental damage, to name a few. They also point to solutions and offer inspiration to take action.

Well-known Oaxacan artist Yescka explains the importance of graffiti and street art. “It’s an attempt to reintegrate art into society. I feel that art right now is standing outside society because it belongs to a limited sector of galleries, intellectuals and museums. I believe art is for everybody and that’s why we’re trying to create a link, so that the people can get in touch with art in their everyday lives again.”

The birth of a movement

The birth of a movement

Every year, as schools close down for the summer, teachers in Oaxaca strike to negotiate increased wages and better school supplies, in a tradition dating back to 1981. Unlike in previous years, however, in June 2006 thousands of police officers in riot gear were sent by the governor to break the strike, using tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the teachers’ protest camp in the city center. Scores of people were injured in the process.

The violent crackdown sparked a public backlash against the state government, as people took to the streets in support of the teachers. Fresh protest camps were erected and general assemblies held to facilitate collective decision-making. In many neighborhoods across the city, barricades were set up to control the movement of police and paramilitary groups. Mainstream radio stations were taken over by protesters as a way to disseminate information widely.

During this time, street art was used to condemn the abuses of power that had become so prevalent in the troubled state and to publicly point to a shared reality of oppression. It was an accessible way for people to share information and rally support.

However, in October 2006, thousands of federal police were sent to Oaxaca to regain control of the city. In the 2008 book Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca, internationally recognized visual artist Hugo recounts how he greeted the arrival of tanks and heavily armed troops by painting a message on the ground in his own blood: ni una gota más de sangre (not another drop of blood). Three people were killed that same day — local teacher Emilio Alonso Fabián, resident Esteban Zurita López and American independent journalist Brad Will. Graffiti denouncing Governor Ruiz Ortiz as a murderer appeared throughout the city center.

By the end of November, a major crackdown in the city center saw the last encampments and barricades torn down by the Federal Preventative Police, marking the end of the teachers’ occupation. Students relinquished control of a university campus they had occupied for months. Protesters and bystanders alike were assaulted, arrested and in some cases disappeared and tortured, with no way to tell family members where they were.

For a few months the protests died down, but by the time the school year ended again in May 2007, the street art scene in Oaxaca exploded, amid ongoing peaceful protests aimed at the state government. In the 2009 book Protest Graffiti Mexico: Oaxaca, renowned Oaxacan-born singer Lila Downs said of the burgeoning street art movement at that time: “As repression continues, the symbols become stronger, and they come to life.”

The legacy lives on

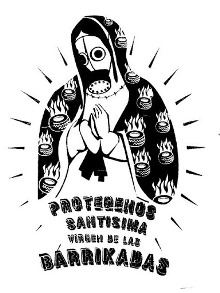

Some quintessential images from that early period can still be found in Oaxaca today. The Virgin of the Barricades is a notable example that depicts the Virgin Mary, a central figure in Mexico’s overwhelmingly Catholic religious life, wearing a gas mask. Flaming tires cover her veil, accompanied by the simple words “protect us”, as she clasps her hands in quiet prayer.

Many artists worked side by side, and others came together to form collectives. The Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca (ASARO) was born during the 2006 uprising, with an eclectic group of artists joining forces to make highly political pieces of street art. Yescka, then a young artist in the collective, also spoke in Teaching Rebellion of that early coming together.

He explains: “It’s always been important to me to express myself freely, to make images that leave a mark, that tell a story of a time, an era or a moment that will never be erased because they live on in our memories. A lot of young people I know, myself included, had always been painting in the streets, but often without any real purpose. What I can thank this movement for is that it made us conscious, gave us reason and meaning — it opened our eyes.”

Two other young artists, Rosario and Roberto, also channeled their creativity in a new direction during 2006. The pair created designs for t-shirts, banners and posters in support of the protests. Even after the uprising had officially been quelled, the duo continued designing and printing t-shirts for the movement. In 2007, they formed the collective Lapiztola, a play on the Spanish words lápiz (pencil) and pistola (gun), with Yankel, an architect and graffiti artist who had also been active during the 2006 protests.

“Our style emerged from the need to express and demonstrate against what has been happening in our city,” the collective explained in a press statement. Lapiztola’s work conveys poignant ideas about place and poverty through stencil-work and graffiti. A frequent motif of their work is the portrayal of a hard-working individual juxtaposed with a flock of birds, perhaps representing freedom from life’s harsher realities.

Like many other Oaxacan street artists, the members of Lapiztola have showcased their work at numerous exhibitions in Mexico and abroad. An adaptation of a mural titled El maíz en nuestra vida (Corn in our lives), originally painted for a festival in Cuba, recently found its way onto the streets of Oaxaca.

Like many other Oaxacan street artists, the members of Lapiztola have showcased their work at numerous exhibitions in Mexico and abroad. An adaptation of a mural titled El maíz en nuestra vida (Corn in our lives), originally painted for a festival in Cuba, recently found its way onto the streets of Oaxaca.

The piece depicts a young woman aiming a rifle at scientists dressed in white hazmat suits, leaning over long stalks of corn. The piece links in with current protests across Mexico, the birthplace of maize, against the widespread introduction of Monsanto’s genetically modified corn.

Internal divisions

While the Oaxacan street art scene is made up of a diverse mix of artists and causes, a handful of the better-known collectives have recently become embroiled in a heated conflict. One artist is currently facing legal action for sexual assault and the projects he is associated with have come under fire from a group of women calling for justice to be done.

While the Oaxacan street art scene is made up of a diverse mix of artists and causes, a handful of the better-known collectives have recently become embroiled in a heated conflict. One artist is currently facing legal action for sexual assault and the projects he is associated with have come under fire from a group of women calling for justice to be done.

Battle lines have been drawn. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this war has also been waged by applying paint to concrete.

Graffiti and stencil work denouncing the artist in question can be found scattered across the city center. The collectives associated with the accused artist have plastered statements on public walls, explaining their stance and distancing themselves from the alleged assault in February 2014.

It seems Oaxacan street art is also being used to highlight divisions that exist within the movement itself. Even progressive social movements can mirror the wider problems of the societies they belong to. Violence against women in Mexico has reached epidemic proportions in recent decades. The very real issues of machismo and patriarchy need to be adequately addressed, both beyond and within Mexico’s social movements.

Raising consciousness

Author Louis Nevaer helped document the rise of street art in Protest Graffiti Mexico: Oaxaca. He says street artists have a role to play in helping to empower and lift people out of ignorance. “In Oaxaca, graffiti artists are modern-day scribes,” Nevaer writes, “passing the written word to people in rebellion against injustice.”

While printing presses and radio stations can be shut down, street artists enjoy relative freedom to communicate with their fellow citizens. After all, graffiti that has been painted over simply becomes a blank canvas for someone else to use. “They cannot stop us, because the people are with us,” Ana Santos, a pioneer in Mexico’s graffiti movement, told Nevaer. “We are the people.”

“In a way I feel like we revolutionized art,” says Yescka, highlighting the wider social transformation that came out of Oaxaca’s 2006 uprising. “That was when I began to understand [the true] meaning of art: making people more sensitive, raising consciousness, and creating new spaces for artistic expression.”

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/revolutionary-street-art-oaxaca/