Kurdish women gather in Istanbul to welcome the remains of Sakine Cansiz, January 2013,. Photo: Sadik Gulec / Shutterstock.com

The prison memoirs of Sakine Cansiz, Kurdish resistance leader

- January 10, 2020

Land & Liberation

In her memoirs, the Kurdish revolutionary leader Sakine Cansiz describes her life and resistance during the 12 years she spent in Turkish prisons.

- Author

Seven years ago, the Kurdish freedom movement lost one of its most iconic leaders. In the offices of the Kurdish Information Center in Paris, Sakine Cansiz, along with two of her comrades, Leyla Şaylemez and Fidan Doğan, was murdered by an agent of the Turkish intelligence agency MIT. Cansiz was a revolutionary leader and a hero of the Kurdish resistance who co-founded the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 1978 and initiated the Kurdish women’s movement. She dedicated her life to the struggle for freedom.

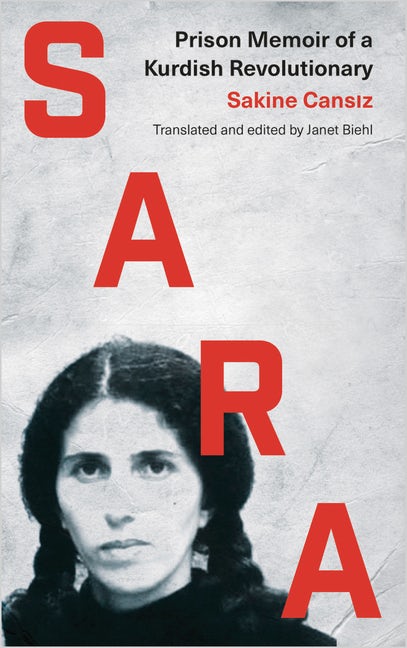

Sakine Cansiz’ “Sara: Prison Memoir of a Kurdish Revolutionary,” translated by Janet Biehl and published by Pluto Press.

In her memoirs, translated to English by Janet Biehl and published by Pluto Press, Cansiz recounts her childhood in Dersim, her defiance towards the traditional patriarchal gender system, and how she became an organizer for the Kurdistan Revolutionaries, a precursor to the PKK. Mere months after attending the founding conference of the PKK in November 1978, she was arrested and subsequently spent 12 years in a Turkish prison where she and her incarcerated comrades suffered innumerable hardships and physical and psychological torture. Her refusal to succumb to the pressure and her dedication to the cause earned her the respect of Kurdish revolutionaries and their allies both inside and outside of prison.

What follows is an excerpt from the second volume of her memoirs, Sara: Prison Memoir of a Kurdish Revolutionary, in which Cansiz describes how she and her friends celebrated Newroz, the Kurdish new year, and how they learned about the death of Mazlum Doğan, another co-founder of the PKK and a leading cadre. Mazlum’s suicide subsequently became a touchstone for future prison resistance.

The Newroz of Mazlum Doğan, March 21, 1982

The days leading up to Newroz were tense. This would be my second Newroz in the Diyarbakir dungeon. The previous year had seen death fasts. Now we were isolated. Interrogations had continued throughout the prison, and betrayals were rampant, especially in the Elazığ group — the band of traitors around Şahin [Dönmez], Ali Gündüz, Erol Degirmenci, and Yıldırım Merkit validated the enemy’s prison policy.

New prisoners arrived in our ward and were taken to interrogation. I knew some of them personally, others only by name. The enemy coerced prisoners into writing statements, where they responded to dozens of questions and declared regret for their past behavior. If the enemy didn’t like a statement, he had them write another. Some arrestees had decided in advance to betray, and they freely allowed the enemy to use the statements. When someone well-known defected, the betrayal was shocking.

We observed the new arrivals surreptitiously. When they went to the toilet and had to wait in line there, we’d rummage through their trash and sometimes find torn-up confessions. It was good to read them. We kept the paper scraps, reassembled them, and hid them so we could use them later in court if necessary. We didn’t let all the friends read all the statements, and we didn’t tell everyone the specific names.

Near our ward, a former guardroom was transformed into a torture chamber, equipped with hooks, electroshock and other instruments. Women newcomers were interrogated there before being brought to our ward. None of the torture instruments there were unusual, but it was all abnormal.

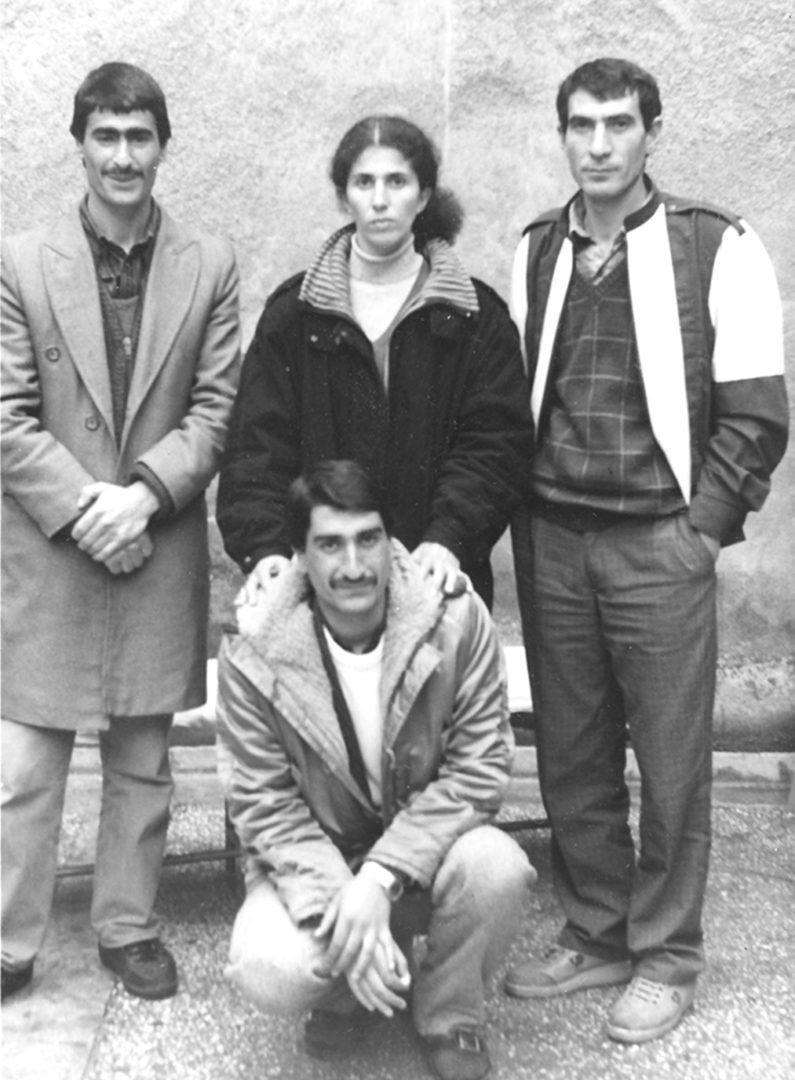

Four prisoners at Diyarbakir prison, undated. Standing, L to R: unidentified, Sakine Cansız, Ali Asker Özdoğan; at front, Fethi Yıldız

“They’re preparing this torture room for us,” I told the other women prisoners. “Maybe for special interrogations, but there’ll be torture every day. The enemy is trying to force everyone to defect, even us. He’ll probably start by singling out certain people.”

“They’ll isolate certain prisoners and try to get them to inform. Maybe rape them. We can’t sit back. If we don’t defend ourselves, he’ll rape us all.” Everyone said with determination: “Then we’ll kill ourselves. These repulsive bastards aren’t going to touch us.” Up until now women had been raped only during police interrogations, but now they would presumably start in prison. We wouldn’t allow it. We’d resist together. This wasn’t a decision for the men friends. If women were going to be coerced in special ways, we’d take special action against it.

We discussed what action. “We could do a mass suicide action, through self-strangulation. Or we could beat our skulls against the wall until they break. That’s our only means of resisting an attack.” Everyone agreed. We shared our decision with a few honest women from other [political] groups. Then as if we’d made a pact, our spirits rose. We all put on thick socks and sweatpants under our skirts. But then, because of the falanga, we mostly did that anyway — Esat [Oktay] took special pleasure in clubbing naked legs.

In the next few days, the guardroom was quickly emptied out again, so it looked as it had before. The doors to the corridor weren’t even locked. What was going on? Had someone died during torture? Or had we been overheard? Had we disrupted the enemy’s plan? We speculated excitedly. Strange, how fast our moods could shift! State of mind is so important in confronting the enemy. We could spite him just by holding firm to our lives and convictions.

We absolutely wanted to celebrate Newroz, knowing the party outside would also do certain actions. But there was so much we didn’t know. We weren’t allowed to have even the slightest contact with the men. “The friends must be planning something,” we guessed. We trusted them, they were only our hope.

We wrote a Newroz declaration. Cahide [Sener] painted a symbol for the New Year festival, and we hung it on the wall in a spot where it wasn’t visible through the door slot. It was about the size of two pages. We brought out some candles we’d hidden and cut into small pieces. We arranged them on the floor so they spelled “Biji Newroz,” and we had enough to write “Biji PKK” too. We lit the candles, took a moment of silence, then read our declaration aloud. Then we danced halay in a half-circle.

A few friends stood watch at the door so the soldiers couldn’t see anything through the slot. We didn’t care if they came in after the celebration. But it was Newroz, who could stop us? A few people from other [political] groups took part in the celebration. Others slunk into the other ward, afraid the enemy would storm in and beat them. That was sad, but we let it drop, so caught up in the excitement were we. More and more people joined the halay, and the half-circle got wider. Afterward a nice theater piece was performed. It was an important celebration.

Despite the huge racket we made, no soldiers came to take a look. Why? Something seemed off, but what? Had there been actions outside? Why else would the enemy leave us alone on such an important night? Newroz without beatings — it just couldn’t be! Or maybe someone inside the prison had done an action. Had the men started another death fast? Oh, this time we absolutely would join.

We pressed our ears to the door but couldn’t hear anything from the corridor or the nearby wards. Bedriye pounded her fists on the wall and chanted, “Biji Newroz, biji PKK!” But only a weak echo answered her.

The silence lasted for days, dead silence, even during the evenings. Had the daily beatings become so routine that their absence now unsettled us? Had some disaster happened? Dammit, we women didn’t get any news — it was like a prison within a prison. The uncertainty was nerve-wracking. We only knew what we heard from the next ward over, or from some individual prisoner en route to the hospital. Sometimes the friends even welcomed defectors, before realizing what they were. We tried to find out about other prisoners from the guards.

New prisoners were also our main way to get information from outside. The friends who distributed food would take it down the lower ward, escorted by a guard to keep them from talking to each other. One day we arranged with the ward leader that during food distribution, if the soldier-guard tried to come in, she would stall him at the door. Meanwhile Gültan would ask a new prisoner, Bezar, for any news.

I waited on the stairway from the upper level. The minutes dragged by, the wait was interminable, and I feared the worst. Then Gültan [Kışanak] emerged and stopped at the foot of the stairway. Something wasn’t right. She seemed to be limping, her head was hanging, and she was sobbing. “Gültan, what’s going on? Tell me!”

When she raised her head, I saw tears in her eyes, and she was deathly pale. My heart stopped. Whatever it was, it had to be bad.

I followed her into the small kitchen, which stood empty. We often came here when we wanted to talk and didn’t want others to overhear. She was still crying.

Sakine Cansız with photos of Leyla Qasim and Mazlum Doğan on the wall behind her, Çanakkale prison, 1990

“What’s going on? What happened?” I asked again.

She hugged me. “Mazlum.”

My arms fell, my heart seemed to want to escape my body, and I froze, my eyes brimming with tears. Mazlum? … Mazlum? What’s happened?

Gültan managed to choke out, “They say he hung himself on Newroz.”

“What! Hung himself? He’d never do that! The enemy’s lying! The enemy murdered him, then called it suicide. I guarantee that’s what happened.” I choked up too, as hatred welled in me. How far would the enemy go? Would he kill off the whole leadership cadre? We had to do something!

Later Aysel came in, crying uncontrollably. Word got around. Mother Durre beat her chest and wailed so bitterly, it must have been audible outside.

Just before Mazlum’s mother, Kabire, was released, she had said, “If only I could see Mazlum one more time.” They hadn’t allowed it. And Baran couldn’t give him the hug she’d promised. Mazlum … Mazlum … Mazlum … No one wanted to believe it. Time stood still.

That evening we held a memorial service. Everyone participated. I gave a eulogy, and after a moment of silence, we sang militant songs. Mazlum’s action filled our hearts with hatred but also brightened them and united us. It shamed those who’d shown weakness.

What had been Mazlum’s purpose with this action? Many couldn’t understand it at first. Earlier he had written: “Surrender leads to betrayal, resistance to victory.” Slowly we realized that he’d intended to send us a Newroz message: Resistance is life!

When Hayri [Durmus] learned that Mazlum had hanged himself, he immediately saw it was “a political action of great significance.” Last May the resistance had been broken. Since then, the enemy had intensified his brutal campaign to induce all the prisoners to defect, and it was showing results. The leadership cadres knew something had to be done. Mazlum understood that prison life as a totality was organized to destroy people’s personalities, to annihilate their individuality. He had seen the danger and tried to prevent it. Aware of his historical responsibility, he had paid the price alone. Here where we all breathed the same air, his splendid fire had burned right next to us. He had commemorated Newroz in an action that hit the enemy directly. He ripped away those ever-tightening snares, warned us against delay, and succeeded in halting the betrayals for a time.

At first, many didn’t grasp the secret of his heroism. That was natural—not everyone can use death to give life meaning. Not everyone can find beauty in harsh conditions and still look death in the eye. Many feared life as much as they feared death and died a thousand deaths even while living.

And we were still pressured, knowing this one action wouldn’t stop the betrayals altogether. I felt it deep in my heart. But surely the necessary action would come.

We hadn’t done justice to Mazlum during life. Now in death, he defined the word dignity, and his Newroz action would have ripple effects. It would revive the spirit of freedom and unity. Now we would discuss new forms of resistance, and our subsequent actions would mutually enlarge and complement this one.

These events affected us women deeply, and we awaited a signal for action. It didn’t occur to us to get active ourselves. But then, what were we supposed to do? We’d always assumed a party decision was required before we could organize resistance. “The organization has to start anything,” we thought. And how could we do anything if the men were quiet? But it was horrible to just wait all the time, and we got impatient. The preconditions for an uprising were more than ripe.

In the wake of Mazlum’s action, all the prisoners searched their souls. Not just the leadership cadre but everyone connected with the party looked for how to proceed. Mazlum’s action became a milestone event for PKK resistance. From now on, we would all measure ourselves against his commitment. On one side was the infamy of betrayal in a situation of terror; on the other side was the greatness of Mazlum’s heroic act. He had opened a new horizon, and hearts that were already flowing toward it wouldn’t wait any longer.

You can order copies of Sakine’s memoirs from Pluto Press:

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/sakine-cansiz-prison-memoirs/