Photo: PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, Museum of History & Industry

When workers ran the city: the 1919 Seattle general strike

- February 6, 2019

Exactly 100 years ago today, workers in Seattle launched a general strike and ran their city for five days, placing it under direct-democratic control.

- Author

For the US working class, the end of WWI was a time of both danger and opportunity. On October 25, 1919 The Nation magazine made an extraordinary claim that 1919 was the year of the “revolt of the rank and file,” a time in which “authority cannot longer be imposed from above; it comes automatically from below. This is the revolution”.

The Nation was not that far off. Revolution was in the air, both in the US and around the world, and workers engaged in general strikes and factory occupations to make it a reality. In the US, the climax of the wartime class struggle lay in Seattle, where workers launched a general strike and for five days took control over the city.

Revolutions also swept Mexico and Russia; a workers’ uprising erupted in Germany; a revolutionary government came to power in Hungary; socialists took over Vienna; insurgencies spread throughout the collapsed Ottoman Empire; workers took over factories in Italy and the Netherlands; independence movements were in the ascent in many colonies; and a general strike took hold in Winnipeg, Canada.

Wartime wildcat strikes had threatened to disrupt war production. My book, When Workers Shot Back: Class Conflict from 1877-1921, documents the US government’s response to the strike by introducing a temporary labor planning policy to arbitrate labor conflicts. This arbitration scheme — a prototype for later New Deal labor relations laws — actually fed the strike wave, as workers further expanded newfound gains by continuing to organize, escalating their tactics, expanding mass support and circulating their struggles.

Workers’ radical actions were on a rise: between September 1917 and April 1918, workers carried out general strikes in six cities. From 1915 to 1917, the number of strikes tripled to a stunning 4,359 and the number of workers on strike rose by 250 percent to 1.2 million. By 1919, the number of strikes leveled out at about 3,400 but the number of workers who struck quadrupled to 4.1 million.

The November 11, 1918, armistice unleashed a coordinated multi-pronged roll-back of the wartime gains. Militant workers, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), socialists, anarchists and other dissidents were violently suppressed, and many hundreds were deported. Pay increases and shortened work hours were rolled back and many thousands of industrial workers were thrown out of their jobs.

But workers were not slowing down. The Seattle wartime strike endured, as did militancy in the steel industry — where workers organized a general strike in 1919 — and the coal mines — which would be rocked by strikes and armed worker rebellions for a few more years. In February 1919, workers in Seattle shut down the city and re-opened it under worker self-management.

For just a few days, the general strike demonstrated that workers would tactically escalate to establish a vibrant living example of what CLR James called a post-capitalist “future in the present”.

Circulating the Struggle

On January 9, 1919, nearly two months after the armistice, 16,000 members of the Marine Workers Affiliation went on strike against a Shipbuilding Labor Adjustment Board (SLAB) arbitration ruling intended to divide and conquer the shipping industry workers. By January 21, the strike had grown to 35,000 skilled shipbuilders and other shipyard workers. The workers were protesting the continuing wartime wage controls by which the international unions, the US Navy, and US Emergency Fleet Corporation — which was controlled by big business — collaborated to set wages under the authority of the SLAB, often awarding the highest wage increases to skilled workers.

Skinner and Eddy shipyard workers leaving. PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, Museum of History & Industry

Although the war was over, SLAB continued to assert control over wages and issued an award without a raise. In response, the shipyard workers voted to begin the strike on February 6. Soon, their proposal to the Seattle Central Labor Council (SCLC) to take over the shipping industry was expanded into taking over control of the entire city.

With some of the SCLC leadership out of town to plan a national action on behalf of San Francisco labor leaders Tom Mooney and Warren K. Billings — who were jailed on trumped up charges of setting off explosives at a 1916 pro-war parade — the Central Labor Council asked its affiliated local unions to poll members about whether they would join a general strike to support the shipyard strike. Over the next two weeks 110 locals voted overwhelmingly to join the general strike. Among those who voted to support the strike were the longshoremen defying the president of the International Longshoreman’s Association who had threatened to rescind their charter if they went on strike.

The general strike that took place over the next several days was the fruit of years of organizing by both workers and supporters throughout the area. The quadrupling of union membership between 1915–18 had made Seattle a strong union town where even the IWW and AFL Metal Trades Council worked together.

Workers in Charge

Unlike other general strikes of the era, the Seattle general strike was more than a show of workers’ power to disrupt production. The Seattle general strike was a demonstration of the power of workers to take over and reorganize both production and reproduction and to lessen the exploitation of the working class by subordinating production to social needs rather than profit.

The SCLC formed a General Strike Committee (GSC) composed of three elected representatives from each local union that had joined the strike, which would run the city for the entire duration of the strike. The GSC became a parallel system of worker self-governance running wet garbage collection, homes for the destitute, a fire brigade, public safety and publicity.

Its operations were effective and efficient. Milk delivery drivers organized distribution to 35 neighborhood milk stations and purchased milk from small dairies. Food workers served 30,000 meals per day to the community in 21 cafeterias. Critical services such as hospitals were kept in operation and continued to be supplied with linen and fuel. There was a semblance of cross-racial alliances illustrated when the Japanese Labor Association of hotel and restaurant workers voted to join the strike.

The GSC organized 300 volunteers for a Labor War Veterans Guard, which operated a community watch that used persuasion rather than force or the threat of violence and served as a counterweight to elite vigilante groups. The watch successfully kept the Skid Row bars closed and troubles to a minimum. It was so effective that, during the general strike, the redundant chief of police said no further police were needed because the unions were providing their own security, and Major General Morrison attested to the peacefulness and orderliness of the city. No one was arrested in relation to the strike during this period, and despite pressures to prosecute strikers under state criminal syndicalism laws, prosecutors were unable to charge even one person with a seditious speech or act.

Workers running the city had such power that employers and government officials, including commissioners, the mayor and the Port of Seattle, approached the GSC for permission to resume limited services or business operations.

Diffusing the leadership of the strike among 110 local unions also reduced the vulnerability of the general strike to the threat of repression. In fact, the GSC wasn’t even the leader of the strike; it was more like the coordinating body.

A grassroots news wire

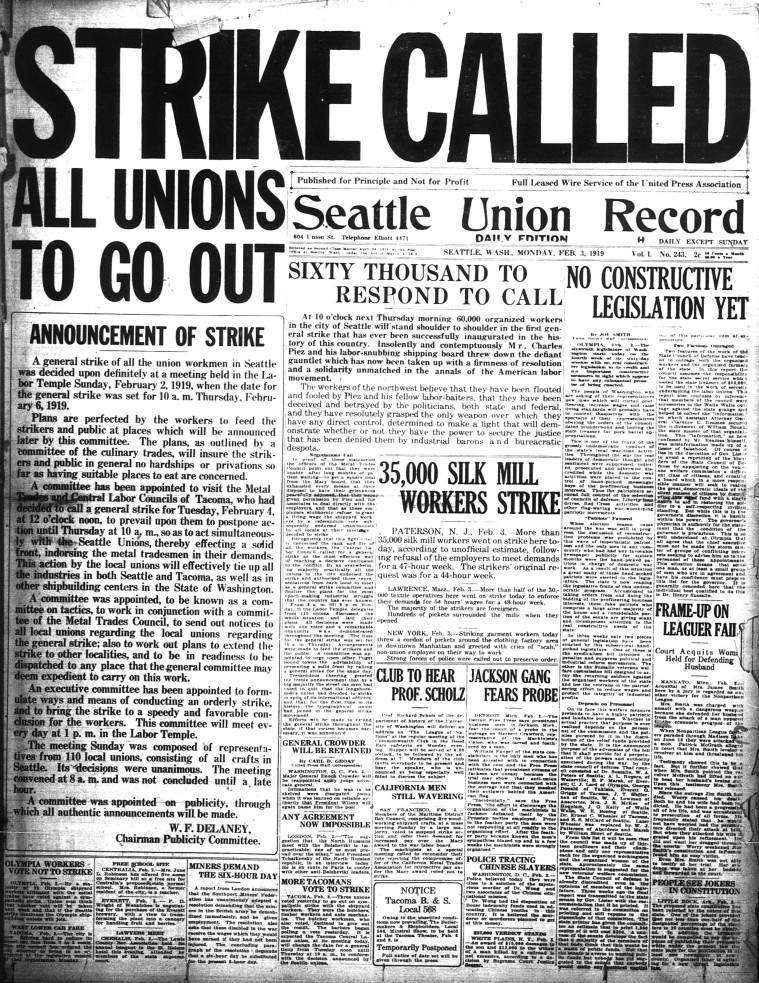

The Seattle Union Record, the General Strike Committee’s daily newspaper, explained the tactics and strategy of the general strike: “They are singularly alike in nature. Quiet mass action, the tying up of industry, the granting of exemptions, until gradually the main activities of the city are being handled by the strike committee.”

The Seattle Union Record, the General Strike Committee’s daily newspaper, explained the tactics and strategy of the general strike: “They are singularly alike in nature. Quiet mass action, the tying up of industry, the granting of exemptions, until gradually the main activities of the city are being handled by the strike committee.”

The Seattle Union Record summed up the qualitative difference between a strike, which applies leverage to shut down production, and the general strike they had launched which took over production to reorganize and subordinate it to social needs:

NOT THE WITHDRAWAL OF LABOR POWER, BUT THE POWER OF THE STRIKERS TO MANAGE WILL WIN THIS STRIKE … Labor will not only SHUT DOWN the industries but Labor will REOPEN, under the management of the appropriate trades, such activities as are needed to preserve public health and public peace. If the strike continues, Labor may feel led to avoid public suffering by reopening more and more activities, UNDER ITS OWN MANAGEMENT.

The workers’ paper provided a daily source of information that flowed outward from the GSC to the strikers and their supporters and back again with news and information to the GSC. Strikers produced and distributed the newspaper. Although its production was centrally organized and subject to possible disruption, it was less vulnerable than the telegraph or telephone — both owned by corporations.

The centralized horizontal organization of the GSC and the use of a newspaper to establish two-way communication between the strike coordinators and the rank-and-file were an expression of the lessons strikers had learned over the previous decades about coordinating a workers’ insurgency.

Reorganizing production and power relations

The Seattle strikers replaced the elite-controlled local government with one run by the workers and the wider community. The GSC supplanted the dominant system of organizing life in the city according to representative democracy and capitalism with a new system of direct self-governance and a needs-based production plan.

The strikers did not waste any effort asking for changes or contending for more power. Rather, the strikers took over and ran their workplaces and communities deciding what they needed, how much work was required to provide it and with whom they would share both the work and output of their labor.

Their general strike was qualitatively different from any other strike, general or otherwise. They did not shut down production to demand concessions from the factory-owners, as was common during WWI. That would have left the capitalist relations of production in place. Rather, the workers made the decisions themselves, shifting the strike beyond just disrupting capitalist relations and instead carving out a short-lived autonomous space where they could exercise their multiple visions of what life could be like

The Seattle General Strike is unique in American history. Perhaps more analogous to the 1871 Paris Commune or the seizure of vast estates by the Mexican revolutionaries over the preceding decade, the Seattle general strike shows what is possible when workers non-violently seize control of the means of production and reproduction.

The Ruling Class Regroups

The storm clouds of repression began forming over Seattle rapidly. The state Attorney General and University of Washington President Henry Suzzallo, who was also the Chairman of the State Council of Defense, called upon Secretary of War Newton Diehl Baker Jr. to send in troops. Nearly 1,000 sailors and marines were deployed around the city. They were joined by US Army troops from Camp Lewis who set up machine guns, although it was unclear exactly at whom they were pointed.

Suzzallo used his university’s Reserve Officer Training Corps students as paid uniformed guards. The private Kiwanis service club, whose membership included professionals and elites, advised its members to stock up on arms in preparation for a fight. Seattle Mayor Hanson added 600 more police, armed 2,400 special deputies, and requested that Governor Lister sent in the National Guard. With his forces in place, the mayor issued an ultimatum for the GSC to end the strike by February 8.

As the strikers considered the mayor’s ultimatum, the old order reappeared at gun point. The business newspaper The Star began to distribute its paper again, guarded by police mounted on trucks with machine guns. The GSC gathered and voted 13 to 1 to end the strike. But after a dinner break the GSC returned and reversed itself, voting to continue the strike.

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) intervened to break the general strike, demanding that workers of its affiliated locals return to work. The AFL leadership understood that the backbone of the Seattle strike was formed by local unions defying their own international unions and violating its contracts with employers. Rather than serving the larger class interests of their fellow workers, the AFL unions had their contracts and organizational prerogatives at stake.

The AFL’s influence over its members was mixed at best. The streetcar workers returned to work but offered to go back out when the GSC called on them. The teamsters also returned to work but they were expected to vote in favor of a strike again. When the GSC voted to end strike on 11 February, the shipyard workers continued their strike. In October 1919, longshoremen in Seattle refused to load a shipment of 50 freight cars containing guns manufactured by Remington Arms for the counter-revolutionary White Russians fighting the Soviet government.

In the meantime, the labor printing plant and the offices of the local Socialist Party and IWW hall were raided and 39 Wobblies were arrested. The general strike was broken by the combined force of capital, the state, and the AFL, a combined force that the striking workers could not fight.

Practicing Counter-Power

The Seattle General Strike demonstrated that informal groups of workers building counter power on the shop floor could go beyond disrupting production, democratically reorganizing and redirecting it to serve human needs.

The general strike established workers as the power-holders in the city. Self-organized workers shifted control almost imperceptibly by re-appropriating the existing resources and wealth and redirecting it for the needs of reproduction. The genius of the workers’ tactics and strategy was to avoid direct contestation over power. Such a conflict would have inevitably meant the asymmetrical use of force and violence that the workers could not expect to win in one city alone. As the History Committee of the General Strike Committee wrote in March 1919,

Our experience … will help us understand the way in which events are occurring in other communities all over the world, where a general strike, not being called off, slips gradually into the direction of more and more affairs by the strike committee, until the business group, feeling their old prestige slipping, turns suddenly to violence, and there comes the test of force.

When the efforts by the insurgents towards self-governance during a general strike take on the form of a dual power structure, it effectively reorganizes society. Re-appropriating the means of production and reproduction displaces the existing institutions that govern both the society and the economy. In this situation, a general strike takes on revolutionary aspects insofar it flips the traditional power balance, disarming elites while empowering the general population.

The workers managed to take over control of Seattle without the use of violence. The Seattle Union Record explained the reason for the absence of violence:

Apparently in all cases there is the same singular lack of violence which we noticed here. The violence comes, not with the shifting of power, but when the ‘counter-revolutionaries’ try to regain the power which inevitably and almost without their knowing it passed from their grasp. Violence would have come in Seattle, if it had come, not from the workers, but from attempts by armed opponents of the strike to break down the authority of the strike committee over its own members. We had no violence in Seattle and no revolution. That fact should prove that neither the strike committee nor the rank and file of the workers ever intended revolution.

By transforming disruption into transcending capitalist social relations, a general strike could provoke a revolution without the need for workers to take up arms under certain conditions. A general strike that places the means of production in the hands of the community and subordinates the economy to direct democratic worker control, can only succeed in the long run if the strike is spread throughout a broad geographic area, expanded into other critical sectors of society and the economy and carries broad support among the population. Without such a re-composition of the working class, a general strike in a single city is unlikely to be sustained and to prevail, especially when elites mount an armed counter-attack.

As the Seattle Union Record documented, elites were the only ones prepared and willing to use violence as a tactic. When the GSC called off the general strike, elites had aligned police, National Guard, military, vigilante forces, and the AFL leadership against the worker controlled free city.

The Lessons of the General Strike

What ultimately doomed the general strike was the elite’s threat to use force. Limited to a single city and surrounded by the forces of repression, the strikers had little chance to main their control over the city. The strikers couldn’t disarm local elites, expropriate and redistribute their property or circulate their struggle beyond Seattle.

When the forces of repression assembled outside Seattle there was no show of mass popular support to counter it. Seattle was a revolutionary island in an ocean of repression.

The Seattle general strike ultimately failed because it was paralyzed between demobilization and de-escalation, on the one hand, and a generalization and escalation of the strike into a revolutionary situation, on the other. The tactical escalation to a general strike was sufficient to force elites to temporarily cede control, but insufficient to sustain or expand it.

Presented with the choice between an intensification of tactics into the unknown or a de-escalation to extract concessions (in other words, between reform or revolution), the strikers opted for de-escalation.

With the storm clouds of repression blanketing the country and the wartime strike wave over, they decided to end their strike to avoid the threat of violence. Nonetheless, while the Seattle strike lasted for only five days, it provided a glimpse of the possibility for workers to take control and self-manage a major US city.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/seattle-general-strike-1919/

Further reading

Offshore finance: how capital rules the world

- Reijer Hendrikse, Rodrigo Fernandez

- February 8, 2019

The gentrification of payments

- Brett Scott

- February 4, 2019