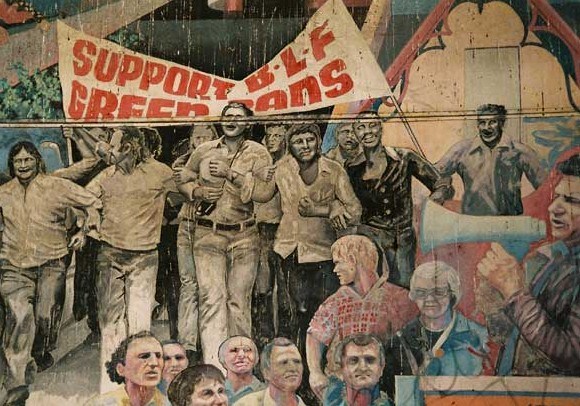

BLF members and leader Jack Mundey on the site of a Green Ban, 1973. Photo: Still from "Rocking the Foundations" 1986, Bower Bird Films and Ronin Films.

Sydney’s Green Bans: worker boycotts that saved the city

- April 20, 2019

City & Commons

Faced with a construction boom in the 1970s, frontline neighborhoods and unionized construction workers in Sydney formed a radical coalition to protect their communities.

- Author

The destruction of heritage buildings, the encroachment of urban development onto green spaces and the gentrification of working class neighborhoods are flash-points of social conflict in expanding cities around the globe.

Communities that mobilize to protect their public spaces, services and culture can protest and call public meetings, or take to the courts and pressure the powers-that-be, but corruption, asymmetrical power and the influence of money can overpower them and make community consultation impotent. When all else fails and neighborhoods on the front line of speculative development are facing the wrecking ball, what options do they have to protect the commons of public space, services and culture?

Consider the radical and effective solution that emerged in Sydney in the 1970s: the Green Ban.

The people versus the speculators

The Green Bans were a series of worker boycotts of projects considered socially, architecturally or environmentally damaging to the local community during Sydney’s speculative construction boom of 1971-1974. Unionized construction workers would simply leave their tools in their toolbox and refuse to enter the building site.

The boycotts were initiated not by union leadership, but by a public vote in open assemblies after a community requested the Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF) to intervene.

In the first ever Green Ban dates in 1971, a group of middle-class women of the harbor-side suburb of Hunter’s Hill urgently asked the BLF to save the last piece of natural bushland on Sydney Harbor. Property developers had the site earmarked for a private housing development, and the “Battlers of Kelly’s Bush,” as the women became known, had exhausted all the legal and political options available to them.

The women called a public meeting to gauge local support for more direct action. Over 600 people showed up to request that the union boycott the development. Within months the development was stalled and ultimately discarded, its success sparking a wave of similar requests from other community groups facing socially, physically and environmentally destructive developments.

The union responded to these requests wherever significant community support existed. Local residents would cast votes in public assemblies to decide on a Green Ban, and the union would mobilize when those votes reflected large majorities. Democracy permeated every aspect of the actions, down to the commitment to translate the debates and discussions for the migrant laborers.

This insistence on democratic decision-making for bans and strikes saw the union membership boom throughout the 1970s, reaching some 11,000 laborers at its peak.

Stopping the Wrecking-balls

This “Australian-made” resistance to unhinged development was responsible for saving some of Sydney’s most iconic buildings, parklands and suburbs from demolition: the expansive Centennial Parkland; Redfern’s Indigenous heart, the Aboriginal-run housing estate known as “The Block”; Kelly’s Bush on the shores of the inner harbor; the grand old bank buildings of the Martin Place; the State Theatre, an exemplar of Sydney’s Art Deco boom; Woolloomooloo’s poorest homes on the now heritage-listed Victoria Street; The Royal Botanic Gardens; working-class suburbs like Glebe; and the historic Rocks, Sydney’s first residential neighborhood.

The Green Bans saved a total of 54 sites from bulldozers. Without the Green Bans, Sydney today would be a city without a soul.

At the time, the actions of the Green Bans sparked enormous controversy, and Premier Robert Askin labeled participants as “traitors to this country.” The strategy directly confronted the power of capital to do as it pleases with what is supposed as private property, and empowered the local communities with the sovereignty to determine their own futures.

By giving neighborhoods agency and recognizing the right of workers to rescind their labor, the Green Bans humanized work. They put work at the service of the community, not at the service of profit. This explains the pride on the workers’ faces in the photographs of the times; it explains the dignity in their stance and the confidence in their actions.

Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald, lead campaigner Jack Mundey explained the premise of worker sovereignty that had so enraged Sydney’s financial and political elite:

Yes, we want to build. However, we prefer to build urgently-required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, high-quality flats, units and houses, provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment, than to build ugly unimaginative architecturally-bankrupt blocks of concrete and glass offices… Though we want all our members employed, we will not just become robots directed by developer-builders who value the dollar at the expense of the environment. More and more, we are going to determine which buildings we will build…

Jack Mundey: Working Class Man

The author of this passionate call for humanized work and a social city, Jack Mundey, Secretary of the New South Wales branch of the BLF, was an effective leader who not only was able to build relationships outside of the union and his Communist Party network, but who was willing to put his body on the line and lead by example to defend his city’s heritage, nature and community.

Mundey was able to bring onboard social-democratic Labor Party activists and politicians — even those on the right wing of the party — and involve traditionally conservative community members in the campaign. He practiced transversal politics, finding common interests and consensus across the political spectrum. He rejected ideological purity and recognized the need to connect a grassroots campaign with electoral politics.

Builders Labourers’ Federation leader, Jack Mundey, is arrested in the “Battle for the Rocks” in 1973.

Mundey and the BLF were a local manifestation of a global shift in thinking on the far left. Spurning communist authoritarianism, Mundey’s innovative strategy went beyond the cycle of bargaining and striking and instead pushed the union to participate in the emerging struggles for women’s’ liberation, Indigenous civil rights and LGBT equality. Under his leadership, the union took on a social role, not merely an industrial one. He wrote, “It is no point in winning great wages and conditions if the world we build chokes us to death.”

But the adept leadership of Mundey also points to the weaknesses of the Green Bans. Mundey knew himself that the movement was not sustainable because it was not addressing the greater problem of laissez-faire urban development. The real solutions, Mundey knew, would come in the form of legislation, regulation, consultation and heritage protection rather than ad hoc defensive actions that require high levels of energy, participation, and organization

Mundey understood that heritage listing, environmental protections and mandatory community consultation would engender conditions under which “it will not be necessary for the Builders Labourers’ Federation to be the conscience of Sydney, and we can join those civilised countries which do appreciate their history and the need for retention of some of the best of our past.”

The fight was not just to save an old building here and beautiful parkland there, but to forever safeguard shared natural, physical and social value from the desire for and market imperative of short-term dollar value. Ultimately, however, it was this antagonism between intrinsic values and extrinsic motivations that caused rising tensions within the labor movement that would eventually spell the end of the Green Bans.

A Long Legacy for a Short Life

The legacy of the Green Bans is evident in the salvaged parklands, neighborhoods and heritage buildings and in the historic example of showing us that another city was and is possible. The Green Bans generated formalized community consultation, recognition of cultural and architectural heritage, and fulfilment of social housing needs: the trinity of a balanced approach to development. Their work set the stage for the 1976 electoral victory a social-democratic Labor Party government under the leadership of Neville Wran, which legislated the Heritage Act, the Environment Planning and Assessment Act, and the Land and Environment Court Act, all representing a workable and long-term peace between the belligerent parties.

The Green Bans showed us that coalitions between community groups and unions can win. They showed us that courage, leadership and a will to take a risk can take on powerful interests and unfair laws. In the short lifespan of the movement — lasting for just three years between 1971 and 1974 — the Green Bans shook the foundations of Sydney’s economic and political elite.

The shockwaves that the Green Bans sent out also destabilized the left itself and the very Builders Labourers’ Federation. The union was the site of a bitter war between an old guard intent on preserving a hierarchical power structure, and a new generation committed to democratic principles of the New Left, such as term limitations on elected officials (with a maximum of six years of tenure), salary caps on union leadership positions, equal work hours for union officials as for unionized workers, ententes across the political spectrum and participatory decision-making processes. Even symbolic gestures, such as rejecting invitations to dine with employers and spurning suits, were encouraged.

The Green Ban was the culmination of this democratization process, responding to New Left theorizing about trade union engagement in issues far beyond the traditional mandates of jobs, wages, and conditions. But the audacity of the actions and the threat that democratization posed to the powers and privileges of old guard office holders, together with the stifling effect that the Green Bans could arguably have on employment in the building industry, caused Maoist office holders in the National BLF office to launch a putsch against the unwieldy New South Wales branch, whose leadership and members were the pioneers of the Green Bans movement.

A less assertive union leadership was imposed on the New South Wales Branch, ending all of the Green Bans across Sydney. Fortunately however, developers chose not to return to their blueprints after once having been defeated by the Green Bans, and within a year of the death of the Green Bans, a social-democratic Labor government was elected, legislating for social, environmental, and heritage protections against unbridled development.

The tragedy of the Green Bans is that it was not the construction tycoons nor the hostile politicians nor the police that ultimately brought down the movement, but the union itself, sucked into a savage and self-defeating war over power, position, and praxis.

Opening Old Wounds

Today Sydney is again experiencing significant social conflict over the limits and type of development and growth. The current pro-development regional government has overridden the rules to balance development with community sovereignty. The interests of speculative development reign again.

It is telling that one of the central disputes in the city today is happening in the core Rocks neighborhood, an area that gave birth to some of the Green Bans’ most intense and visible protests.

A mural of Jack Mundey in The Rocks, central Sydney, painted by Portuguese street artist Alexandre Farto.

In the Rocks, a Brutalist public housing masterpiece known as the Sirius is facing demolition; its social housing tenants have already been evicted to make space for a new private development priced at US$86 million. In addition to the Sirius, the government has privatized hundreds of other public housing units in the Millers Point neighborhood, raking in an additional US$420 million.

Should the sale and demolition of the Sirius building go ahead, it will herald the state’s official withdrawal from the social contract that the Green Bans movement created. This was made possible by the 1976 electoral victory a social-democratic Labor Party government under the leadership of Neville Wran, which legislated the Heritage Act, the Environment Planning and Assessment Act, and the Land and Environment Court Act, all representing a workable and long-term peace between the belligerent parties.

The ability of governments and developers to ignore the spirit and override the letter of legislated protections of a city’s commons means that communities must be willing to go beyond the formal avenues of community participation in development decisions. That is, they must be willing to take direct action to protect their shared history, environment, and services.

Learning from the Green Bans

In the conflicts that continually flare up in Sydney and cities across the world, what would occur if local communities were to team up with unions to lead a Green Ban-style movement against speculative development, the destruction of aesthetic value and natural heritage, and the eviction of marginalized people from the city center?

Just like in the 1970s, workers would be faced with dismissal, fines, lawsuits, and outrage. It would likely be easier to quash a Green Ban in Australia today than it was in the 1970s because Australia’s strike laws are among the most restrictive in the world, unionization rates are among the lowest, and organized labor is arguably less democratic than it has been in the past.

Despite the challenged faced by unions, housing activists, environmentalists, and heritage conservationists, we need to seriously consider new ways of resisting urban overdevelopment because a consultative process does not always safeguard against sacking a city’s commons, certainly not where financial influence, deregulation, underfunding of enforcement authorities and outright corruption nullify any attempts by the community to enforce their will.

Just as neoliberal politicians and executives have rescinded from the social pact that produced the Welfare State — defunding schools and hospitals, suppressing wages and worker rights — so too are they rescinding from the urban pact that protected a minimum of environmental, social and physical integrity in our cities. Sydney today is a case in point.

Can tactics like the Green Bans be used in today’s context?

While the challenges activists face today are significant, the challenges that the Builders Labourers’ Federation faced in the 1970s were equally daunting. We should study their example — their tactics and leadership, their organizational model and their coalition building — as a guide for radical activism that goes beyond the standard methods of consultation, advocacy, protest and media engagement.

In campaigning against selling off the urban commons, each city and neighborhood will face its unique challenges and opportunities, weaknesses and strengths, but all can learn from the historic examples of coalition building, democratic decision-making, electoral alliance making and the skilled leadership shown by the Green Bans movement.

In the coming fights for our cities, we will need to go further than what legislated protections can secure: we must demand higher standards of sustainability, accessibility and livability that build cities safe for human consumption.

The Green Bans showed us that by building coalitions between organized labor, community groups and legislative actors, we can ensure a sustainable, social and respectful urban development. The Green Bans not only showed us that another city is possible, but they gave us another Sydney.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/sydneys-green-bans-worker-boycotts-that-saved-the-city/