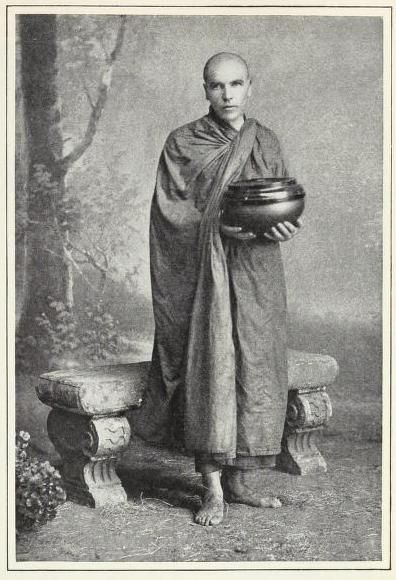

Burmese monks after begging their daily food (1887–1895) Photo: Felice Beato

The forgotten futures of anti-colonial internationalism

- April 20, 2020

Imperialism & Insurgency

The strange story of an Irish Buddhist anti-colonial activist in the heyday of Empire in Asia sheds light on the non-linear nature of radical social change.

- Author

It is the full moon of March 2, 1901, the day of the most important pagoda festival of the year in Burma. The scene is the golden Shwedagon pagoda, the country’s holiest Buddhist site. The area is jam-packed with crowds: monks, pamphleteers and entertainers, stallholders and pious worshipers — and colonial tourists strolling around as if they own the place.

Enter an off-duty policeman, enjoying the scene — only to be stopped in his tracks by a barefoot Buddhist monk ordering him to take his shoes off.

Time slows down.

This pagoda is holy ground. It contains eight hairs from the Buddha’s head, among other relics. In Burma, as in many other Asian countries, you do not wear shoes on sacred ground, or in people’s homes. But in 1901, the colonizers do, as do their soldiers and police.

Shoes have become one of the things separating “sahibs” from “natives” as a superior race, a class apart. Since the Indian Rebellion of 1857 it seemed very important to make these distinctions: the Europeans in Asia were vastly outnumbered by their local subjects.. Cultural hierarchy helped hold this house of cards together.

But the monk who is challenging the policeman … is Irish. He has stopped wearing shoes, shaved his head, donned the monk’s saffron robes and begs his food. His body is a living challenge to the dividing lines of race and power. And he has crossed another line, too: while Empire is supposed to bring the gospel to the heathen, he has converted to native “idolatry,” joined an Asian organization and lives like them — he has gone native.

The symbolism — on this night, in this place — is very powerful. As this monk is supposed to have said, the British had “taken Burma from the Burmans and now desired to trample on their religion.” Religion and power are as tightly linked here as Empire and race: one way the British army keep the Burmese in line is by having cannons pointed at the Shwedagon Pagoda.

With all of this, the monk’s direct action has the desired effect. The policeman makes an issue of it, and the colonial authorities try to exert backdoor pressure on the pagoda trustees to disavow the monk. They refuse, and leak the document they are supposed to sign to this effect, further embarrassing the authorities.

The shoe issue — and the much bigger issue of Empire, race and respect for local culture — runs and runs. In fact, it becomes a central issue for Burmese anti-colonialist organizing for the next eighteen years: imperial intransigence is a gift to activists.

This confrontation is a symbolic one, and takes some explanation if you were not there at the time. But the color line is real, as is the question of who decides in Burma. The moment dramatizes colonial arrogance — and popular resistance.

Trouble from the Irish

As activists, many of us put a lot of energy into trying to construct and amplify these kinds of moments for their symbolic value, and this particular Irishman probably had a lot of experience before this. It is hard to tell, because nineteenth-century working-class migrants like him did their best not to leave too many traces, as shown by his five — known — aliases.

Born Laurence Carroll in Dublin in 1856, he emigrated first to Liverpool and then worked his way to the United States in 1872, hoboing across the country to San Francisco and then sailing the trans-Pacific lines before appearing as a dockworker in Rangoon and becoming the Buddhist monk U Dhammaloka in 1900. This dramatic conversion combined a working-class rejection of Christianity, a falling in love with the Asian cultures threatened by colonialism, and commitment to what he saw as the rational and egalitarian spirit of Buddhism.

However, despite his fondness for telling his own story, there are about 25 years of his life that he drew a quiet veil over. These are the years when Pinkerton detectives battled Irish secret societies (the Molly Maguires); of bitter labor struggles across the US and the growth of anarchism and socialism.

As a monk, Dhammaloka was certainly happy to sail close to the wind. He was tried for sedition at least once, put under police and intelligence surveillance, disrupted the lives of powerful officials, faked his own death and eventually disappeared.

Being Irish was not accidental to the anxieties he provoked. Much of the British army in India was Irish, and with both Indian and Irish nationalism on the rise, the fear of what might happen if they joined forces was a lively one. Kipling’s 1901 best-seller Kim shows the orphaned son of an Irish soldier and an Indian “bazaar woman,” going native and torn between his loyalty to the spymasters of the English Raj — who value his skill with languages and disguise — and his Tibetan Buddhist teacher. For several decades in the early twentieth century, anti-colonial solidarity between colonized Ireland and colonized Asia was a two-way source of inspiration and occasionally activists, often mediated by religion.

Wider Networks and Struggles

Dhammaloka did more than symbolize the massive potential of subaltern religion and the contradictions of imperial hierarchies of race and power; he was an active participant in the anti-colonial Buddhist revival across Asia. He was a massively popular speaker and publisher across Burma; an organization-builder in Thailand, Singapore and today’s Malaysia; involved in Japanese efforts at international Buddhist networking; a disruptive figure in today’s Sri Lanka; and otherwise active in today’s India, Bangladesh, China, Australia and maybe Nepal and Cambodia.

Because of the many biases of the surviving sources on Dhammaloka’s life, it is often easier to see the visible figurehead than the wider movements behind him. But over the course of a ten-year “history from below” research project, Alicia Turner, Brian Bocking and I have looked beyond the one individual in order to glimpse the creative practice of grassroots, multi-ethnic, decolonial networks in these different countries over a hundred years ago — networks that played their respective roles in struggles that ultimately defeated Empire.

Often these networks were rooted in the plebeian cosmopolitanism of port cities. Rangoon, Penang, Singapore, Bangkok and similar locations were deeply multi-ethnic: long-standing complexities of language, religion and culture in the hinterland, coupled with groups like the Chinese diaspora and the Tavoyan ethnic minority, Indian and Tamil migrant laborers and “poor whites” from Europe, saw people thrown together into workplaces, communities and cultural practices that often bore little resemblance to the reified images popularized by Orientalist theories.

When Dhammaloka was put on trial in Rangoon a decade after the shoe incident, he would be supported not only by Buddhist Burmese, but also by the Chinese and Indian bazaars, by a future organizer of Muslim dockworkers and by the local cinema. Despite nominally being Burmese and Buddhist, we find him working with a Shan chieftain and a Sinhalese diaspora merchant, speaking to Tamil and Hindu gatherings, with European and Muslim supporters.

This interconnectedness of daily life found expression in an interconnected subaltern politics and what Leela Gandhi calls the “politics of friendship” across boundaries, in the decades before ethno-religious supremacy and the drive to form nation-states came to dominate movements.

On tour in Ceylon

In 1909 Dhammaloka led a speaking tour of Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka) for Anagarika Dharmapala’s Maha-Bodhi Society, an attempt at bringing together Asian Buddhists from Japan to Ceylon around an imagined pan-Asian identity,. In this campaign we can clearly see the local networks using Dhammaloka as front man to challenge Christian missionaries. We have much of the official publicity for this tour — 48 talks in two months, criss-crossing Ceylon, organizing rallies in cities and villages, often attended by crowds of thousands — as well as some of the talks published in the organizers’ newspaper. We also have hostile responses from the colonial and missionary press; the nervous distancing of more conservative activists; and the notes of a government agent asked to keep an eye on him.

We also have Dharmapala’s diaries, which read like the diaries of someone trying to organize a 1970s rock tour. There are the organizer’s costs and worries when his star speaker falls sick; cheerful notes about good attendance, book sales and donations; the jealousies among the touring group; Dhammaloka storming off and needing to be calmed down; and his sudden departure — apparently because the law had been changed to prevent the tour continuing.

We also see media polemics in which opponents call for Dhammaloka to be deported, while his supporters threaten them with charges for misreporting. We see counter-lectures set up alongside Dhammaloka’s tours, and tom-tom drummers sent to disrupt each other’s meetings. We see police spies sent to take notes of what is said — and publicly challenged from the podium. It all seems … strangely familiar from the viewpoint of today’s movements.

The Bible, the bottle and the Gatling gun

In his talks, Dhammaloka’s often repeated his analysis of colonialism as “the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun” — missionary Christianity, cultural destruction and military conquest. If temperance (opposing the bottle) was uncontentious, public opposition to Empire was of course treason. Challenging missionaries was skirting the boundaries of what could be said and done, a proxy for the wider conflict.

This was quite an “Irish” move: religion in Ireland had long been a terrain of challenge to Empire, since Daniel O’Connell organized what Terry Eagleton calls the first truly modern social movement in the 1820s — challenging systematic discrimination against Catholics in favor of the Anglican church, associated with British rule. Yet, just as at the Shwedagon in 1901, Empire could not trample too heavily on local religion without provoking a reaction. To defend Buddhism against missionary Christianity in Burma was as effective as defending Catholicism against Protestantism in Ireland: local religion was a powerful language of resistance.

Part of what Dhammaloka brought to the job, though, was the freethought (atheism) of radical working-class culture, a view shared by American hobos and English sailors, and with a long history of challenging the Bible on the grounds of consistency, ethics and rationality. Demystifying missionaries’ claims that they were bringing salvation, Dhammaloka told the story of Maori people being advised to look at the sky and pray — and replying “When we look up and pray, you steal the ground beneath our feet.”

As in Linebaugh and Rediker’s Many-Headed Hydra, this was a transnational world of interconnected struggles and debates. When he was being tried for sedition, Dhammaloka wrote to the New York Truth-Seeker, enclosing clippings from an Indian National Congress paper published in Burma; we found them in a Swedish translation in a Minneapolis atheist paper. He wrote:

If the missionaries alone had power, they would doubtless do with me as the clerical Spanish government did on 13 October 1909 with the great and noble martyr Francesc Ferrer.

The anarchist educator Ferrer had been executed after the Barcelona uprising; American activists would commemorate him by creating a movement of anarchist, freethinking schools. Transnational solidarity — in this English-speaking, atheist and anarchist network and Dhammaloka’s own multi-lingual, Buddhist and anti-colonial networks — was part and parcel of this world.

Lessons for today

These multiple, interconnected, diverse subaltern networks and struggles helped to turn the imperial world upside down. Asia — and Africa — started the twentieth century almost entirely part of European empires; a few decades later most were independent nation-states. Since about 60 percent of the global population lives in Asia, this is the largest single social change from below in the last hundred years — and worth paying attention to if we are serious about bringing about change on this scale, or an even larger one like going beyond capitalism.

Yet in Dhammaloka’s day, before Irish independence and the collapse of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires, it was not yet clear that the post-imperial future would take the form of developmental nation-states. This is one reason why Buddhism — spanning Asia from Japan to Ceylon — seemed for a time as if it might offer a non-western path to modernity.

Then, as now, it was hard to imagine radically new futures before they happen; we disagree on where we want to go; and there is always too much to know. So these “forgotten futures” of mass popular mobilization can be helpful to think about the kinds of challenges we now face — in finding a way through the coronavirus crisis, defeating neoliberalism, fighting the rise of authoritarianism and developing a survivable future.

In their own days, activists like Dhammaloka were effective as organizers and as symbols of resistance, but Empire was a horizon it was hard to think beyond. A generation later, nationalist movements would be winning conclusively across the world, and we are now dealing with many of the problems they left behind, from Burma and Sri Lanka to Ireland and South Africa.

If it is clear in hindsight that both authoritarian statism and ethno-religious supremacism were deeply damaging, we can learn something from the more generous alternatives that these particular factions marginalized. We do not know what kind of difference our efforts will ultimately make, within our movements or against our wider opponents; but we can be more confident that they will make a difference.

In the end, Empire was defeated so comprehensively that it is hard to tell the story of that defeat without first evoking the complex details of a largely vanished world. And it was the creative practice of grassroots, multi-ethnic, decolonial struggles over a century ago that ultimately defeated Empire.

If despair today tells us that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, in 1900 it was almost impossible to conceptualize the world after Empire. And yet, it happened.

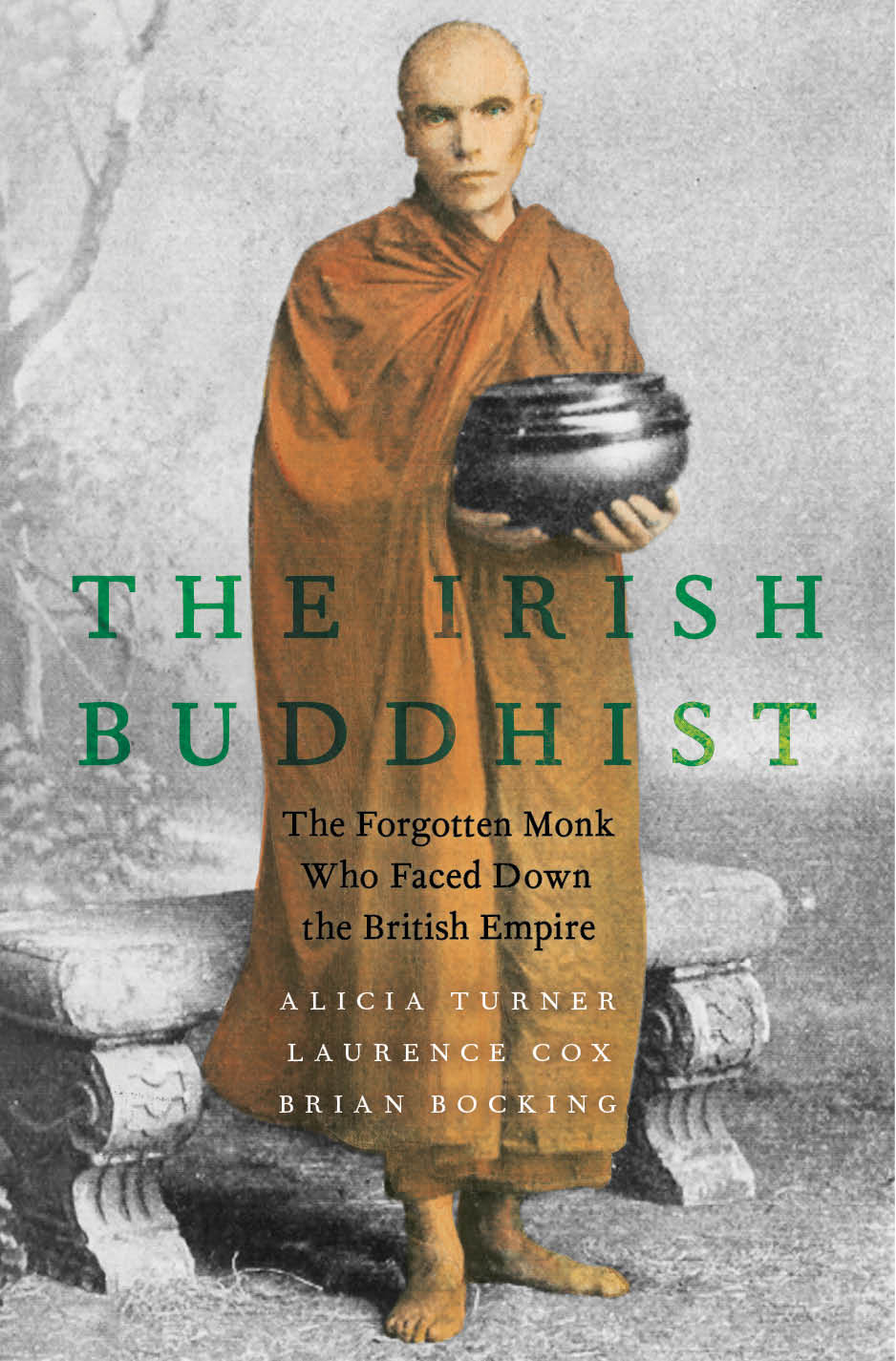

The Irish Buddhist: The Forgotten Monk who Faced Down the British Empire by Alicia Turner, Laurence Cox and Brian Bocking is out now from Oxford University Press.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/the-forgotten-futures-of-anti-colonial-internationalism/