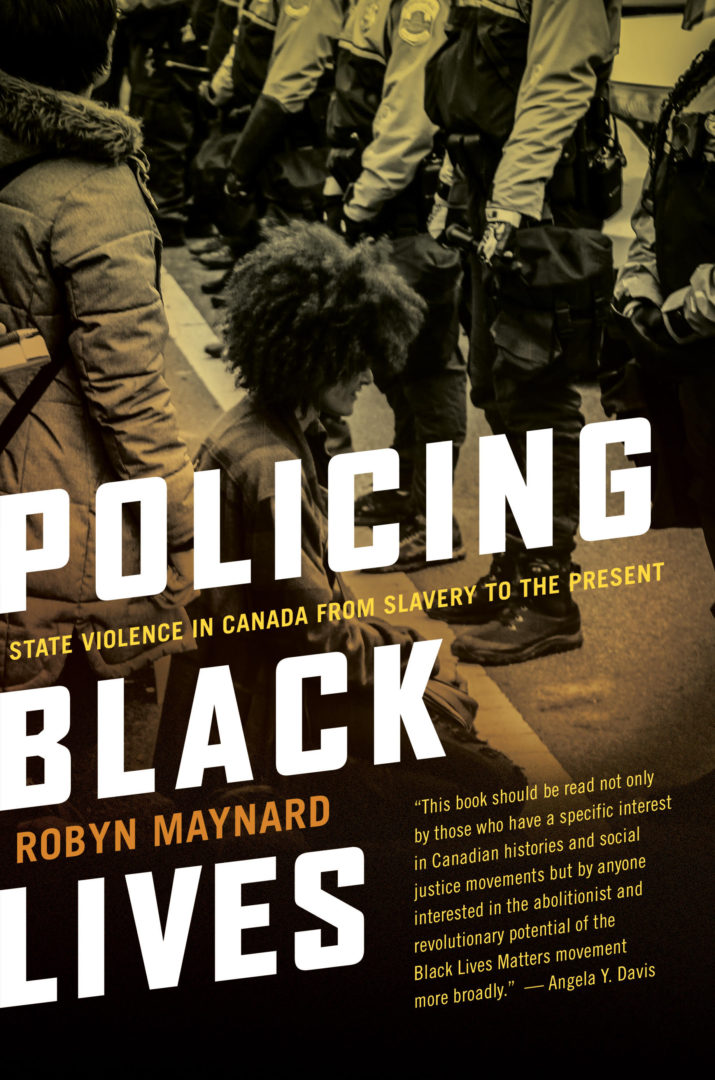

Activists protesting the police killing of Abdirahman Abdi in Mississauga, Canada. August 25, 2016 Photo: arindambanerjee / Shutterstock.com

The struggle against anti-Blackness in Canada

- July 3, 2020

Race & Resistance

Canada, “the land of multiculturalism,” has a long tradition of erasing its anti-Black history – but the Black radical imagination is experiencing a revival.

- Author

We are currently in a moment of historic Black-led rebellions across North America. Even as dominant narratives continue to erase or minimize anti-Blackness in Canada, over 60 protests in defense of Black lives have taken place across the country in recent weeks.

Black-led multiracial crowds, tens of thousands strong, have taken to the streets in solidarity with the protests in response to the killing of George Floyd in the US, and in stark condemnation of the recent deaths of Regis Korchinski-Paquet and D’Andre Campbell — two young Black persons who died during police encounters in recent months in Toronto, Canada.

Cities across Canada, from Toronto, Winnipeg and Hamilton, to Vancouver and well beyond, have seen the rise of Black-led abolitionist struggles. These struggles are collectively voicing a broad chorus of demands to defund, demilitarize, dismantle the police and abolish the carceral systems that it upholds; to remove law enforcement from schools; divorce police from mental health responses; and, to re-invest those public funds into Black, Indigenous and other disenfranchised communities.

Cities across Canada, from Toronto, Winnipeg and Hamilton, to Vancouver and well beyond, have seen the rise of Black-led abolitionist struggles. These struggles are collectively voicing a broad chorus of demands to defund, demilitarize, dismantle the police and abolish the carceral systems that it upholds; to remove law enforcement from schools; divorce police from mental health responses; and, to re-invest those public funds into Black, Indigenous and other disenfranchised communities.

My book, Policing Black Lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present (Fernwood Publishing) was published three years ago. Written during the first stages of the now protracted and expanded #BlackLivesMatter-era, the book was intended as a contribution to the growing movement to overturn state violence against Black lives in Canada. The movement is still ongoing, and the following excerpt may help to provide some context of the broader conditions grounding Black struggle in the contemporary moment.

On State Violence and Black Lives

State violence against Black persons in Canada has, by and large, remained insulated by a wall of silence and gone largely unrecognized by much of the public, outside of brief media flashpoints. Anti-Blackness in Canada often goes unspoken. When acknowledged, it is assumed to exist, perhaps, but in another time (centuries ago), or in another place (the United States). Many Canadians are attuned to the growing discontent surrounding racial relations across the United States, but distance themselves from the realities surrounding racial disparities at home.Most know, for example, the names Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown as victims of anti-Black police violence, but could not name those Black Canadians cited above or recite the names of Andrew Loku, Jermaine Carby or Quilem Registre. A generalized erasure of the Black experience in Canada from the public realm, including primary, secondary and post-secondary education, combined with a Canadian proclivity for ignoring racial disparities, continues to affect mainstream perceptions of Black realities throughout the nation.

In addition, unlike in the United States, systematic collection of publicly available race-based data is rare at the national, provincial or municipal level and at most universities. Together, these factors have led to a discernable lack of awareness surrounding the widespread anti-Blackness that continues to hide in plain sight, obscured behind a nominal commitment to liberalism, multiculturalism and equality.

Anti-Blackness has not always been obscured. During the period of slavery, many slave owners demonstrated no shame in owning Black and Indigenous people as property. For instance, throughout the 18th century, it was common for slave owners to place their names on runaway slave notices in Canada. After slavery’s abolition in 1834, though, anti-Black racism in Canada has been continually reconfigured to adhere to national myths of racial tolerance.

By 1865, textbooks bore little allusion to any Black presence in Canada, erased two centuries of slavery, included no mention of segregated schools (an ongoing practice at the time) and alluded to the issue of racial discord only in the United States. During much of the first half of the 20th century, despite segregated schooling in many provinces, discrimination in employment and housing and significant Ku Klux Klan membership, Canadian newspapers and politicians nonetheless continuously framed the so-called “Negro problem” as an American issue.

The existence of anti-Blackness remains widely unspeakable in many avenues to this day. For instance, in 2016, shortly following the police killing of Abdirahman Abdi, Matt Skof, the president of the Ottawa Police Association, told the press that it was “unfortunate” and that he was “worried” that Canadians would assume race could play a factor in Canadian policing, arguing that those issues were only pertinent in United States. The long history of anti-Blackness in Canada has, for the most part, occurred alongside the disavowal of its existence. Black individuals and communities remain, “an absented presence always under erasure,”as Rinaldo Walcott puts it in Black Like Who?.

An unacknowledged history

Canada, in the eyes of many of its citizens, as well as those living elsewhere, is imagined as a beacon of tolerance and diversity. Seen as an exemplar of human rights, Canada’s national and international reputation rests, in part, on its historical role as the safe haven for the enslaved Black Americans who had fled the United States through the Underground Railroad. Today, it is well known, locally and internationally, as the land of multiculturalism and relative racial harmony.

Invisibility, however, has not protected Black communities in Canada. For centuries, Black lives in Canada have been exposed to a structural violence that has been tacitly or explicitly condoned by multiple state or state-funded institutions. Few who do not study Black Canadian history are aware that dominant narratives linking crime and Blackness date back at least to the era of the transatlantic slave trade, and that Black persons were disproportionately subject to arrest for violence, drugs and prostitution-related offences throughout Canada as early as the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The history of nearly a hundred years of separate and unequal schooling in many provinces (separating Black from white students), which lasted until 1983, is not taught to Canadian youth. A history that goes unacknowledged is too often a history that is doomed to be repeated.

The structural conditions affecting Black communities in the present go similarly under-recognized. In 2016, to little media fanfare, the United Nations’ Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights confirmed that anti-Black racism in Canada is systemic. The committee highlighted enormous racial inequities with respect to income, housing, child welfare rates, access to quality education and healthcare and the application of drug laws.

Many Canadians do not know that, despite being around three percent of the Canadian population, Black persons in some parts of the country make up around one-third of those killed by police. It is not yet common knowledge that African Canadians are incarcerated in federal prisons at a rate three times higher than the number of Blacks in the Canadian population, a rate comparable to the United States and the United Kingdom . Fewer still are aware that that in many provincial jails, the rate is even more disproportionate than it is at the federal level.

In addition to being more heavily targeted for arrest, because so much of Canada’s Black population was born elsewhere, significant numbers of those eventually released will be punished again by deportation to countries they sometimes barely know, often for minor offenses that frequently go unpunished when committed by whites. Black migrants, too, are disproportionately affected by punitive immigration policies like immigration detention and deportation, in part due to the heightened surveillance of Black migrant communities.

Black children and youth are vastly overrepresented in state and foster care, and are far more likely to be expelled or pushed out of high schools across the country. Black communities are, after Indigenous communities, among the poorest racial groups in Canada. These facts, along with their history and context, point to an untold story of Black subjection in Canada.

Surveil, confine, control and punish

Though anti-Blackness permeates all aspects of Canadian society, Policing Black Lives focuses primarily on state or state-sanctioned violence — though, at times, this is complemented with an enlarged scope in instances when anti-Black state practices were buttressed by populist hostility, the media or civil society.

The reason for this focus is simple: the state possesses an enormous, unparalleled level of power and authority over the lives of its subjects. State agencies are endowed with the power to privilege, punish, confine or expel at will. This book traces the role that the state has played in producing the demonization, dehumanization and subjection of Black life across a multiplicity of institutions.

Grave injustices — including slavery, segregation and, more recently, decades of disproportionate police killings of unarmed Black civilians — have all been accomplished within, not outside of, the scope of Canadian law. Not only is state violence rarely prosecuted as criminal, it is not commonly perceived as violence. Because the state is granted the moral and legal authority over those who fall under its jurisdiction, it is granted a monopoly over the use of violence in society, so the use of violence is generally seen as legitimate.

When state violence is mentioned, images of police brutality are often the first that come to mind. However, state violence can be administered by other institutions outside of the criminal justice system, including institutions regarded by most as administrative, such as immigration and child welfare departments, social services, schools and medical institutions. These institutions nonetheless expose marginalized persons to social control, surveillance and punishment, or what Canadian criminologist Gillian Balfour calls “nonlegal forms of governmentality.”

These bureaucratic agencies, too, have the repressive powers generally presumed to belong only to law enforcement. They can police — that is, surveil, confine, control and punish — the behavior of state subjects. Policing, indeed, describes not only cops on their beat, but also the past and present surveillance of Black women by social assistance agents, the over-disciplining and racially targeted expulsion of Black children and youth in schools, and the acute surveillance and detention of Black migrants by border control agencies.

Many poor Black mothers, for example, have experienced child welfare agents entering and searching their homes with neither warrant nor warning — in some instances seizing their children — as a result of an anonymous phone call. Further, state violence can occur without an individual directly harming or even interacting with another. It can be, in short, structured into societal institutions.

The global anti-Black condition

Long after the formal emancipation of enslaved Black populations and the formal decolonization of the Global South, anti-Blackness remains a global condition and continues to have enormous impacts on Black individuals and communities. It is “our existence as human beings,” writes Rinaldo Walcott, that “remains constantly in question and mostly outside the category of a life.” Despite the end of slavery as a legal form of controlling Black movement and curtailing Black freedom, the enduring association of Blackness with danger and criminality was further consolidated, and new forms of policing Black people’s lives emerged.

Under slavery, the policing of everyday Black life was the standard. To use the words of Simone Browne, “[A] violent regulation of black mobilities” was required for slave owners to maintain the institution. Emancipation required new, or at least modified, expressions of racial logics; people designated Black have been homogeneously rendered as menacing across much of the world, and surveilled and policed accordingly. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, criminality, danger and deviance became more fully assigned to Blackness. In the United States, almost immediately after emancipation, newly freed Black men and women were targeted with arrest, imprisoned and forced to perform free labor under the jurisdiction of the Thirteenth Amendment.

In the mid-20th century, Frantz Fanon demonstrated how shared beliefs about the criminal proclivities of Black peoples existed throughout the French Empire, the Southern United States, South Africa and West Africa. In 1970s Britain, Black cultural theorist Stuart Hall critiqued the links between Blackness and violence in the panic surrounding “young Black muggers” that resulted in a significant increase in law enforcement agencies policing Black communities in Britain.

Today, Black men and women in the US remain unduly targeted by criminal justice, in a system of mass incarceration unknown throughout much of the world. In other parts of the world where chattel slavery flourished, such as Brazil, racial profiling and Black incarceration is also endemic.

Given the “global anti-Black condition,” in the words of Rinaldo Walcott, it should come as no surprise that the associations between Blackness, crime and danger continue to have enormous power in Canada nearly two centuries after the British abolished slavery in all their colonies. Black and white Canadians appear to commit relatively equal levels of most crimes, yet the Black population, viewed as dangerous, continues to bear the burden of the “criminal” stigma. Canadian politicians, police and newspapers have, for centuries, linked Blackness or Black “cultures” to criminality and danger.

They have been treated as menaces to be kept out, locked up or removed. From ordinances attempting to ban Blacks from Canadian cities in 1911 and the discovery that the Montréal police used pictures of young Black men as targets for their shooting practice throughout the 1980s to the targeted deportation of nearly a thousand Jamaicans in the mid- to late-1990s, the encoding of Black persons as criminal, dangerous and unwanted holds enormous power across Canadian institutions.

Black subjection has changed forms in important ways in a society that purports to be colorblind. Today, the denigration of Blackness is sometimes difficult to pinpoint. Explicit hatred of Black persons, for example the use of a racial epithet or a violent hate crime, is no longer culturally acceptable. Most Canadians of any political persuasion would largely reject any politic based on open hatred, and would be unlikely to support an open call to bring back “whites only” immigration policies or to re-segregate education and ban Black youth from schools.

This form of racism — while being reinvigorated in some segments of society amid an upswing of white supremacist movements — has largely fallen out of mainstream political favor in an era where formal equality prevails in Canadian law.

The contours of Black freedom

Liberal democracies like Canada continue to practice significant racial discrimination, yet they now do so while proclaiming a formal commitment to equality. It is, after all, writes Saidiya Hartman, “the wedding of equality and exclusion in the liberal state” that distinguishes modern state racism from the previous forms of racism found under slavery. Racism has merely become more difficult to both detect and contest. While many Black people in 21st century Canada officially have rights equal to those of other national subjects, “official” equality means little when it is the state that is both perpetrating and neglecting to act in the face of racial subjugation, neglect and other forms of violence.

It is dangerous to fail to recognize the ways that anti-Blackness has shaped, and continues to shape, the contours and possibilities of Black freedom. Yet, we risk presenting narratives of Black dehumanization as totalizing: “at stake is not recognizing anti-Blackness as total climate,” but also at stake is “not recognizing an insistent Black visualsonic resistance to that imposition of non/being,” explains Christina Sharpe.

By insisting on the persistent devaluation of Black life, it is not my intention to eclipse the very real realities of Black refusal, subversion, resistance and creativity that have flourished, despite centuries of systematic hostility and oppression. Though it is not the primary focus of this book, there exist extraordinary histories of resilience, many documented and more still unwritten, that are a testament to a politics of sustained Black cultural, intellectual and spiritual creative practices, despite policies intended to extinguish these acts.

These histories span centuries. In 1734, an enslaved Black woman named Marie-Joseph Angélique attempted to flee her white mistress. She faced enormous consequences for her insistence on independence and agency. Accused of burning down Montréal, she was arrested, tortured and publicly hanged. In the 19th century, hundreds of free Black men and women in Southwest Ontario risked state and populist repression by forming vigilance committees that resisted white American slave catchers’ attempts to re-enslave Blacks who had escaped their bondage and had fled to Canada. Black communities in the Prairies fought against the impunity granted to the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th century.

A revitalization of Black resistance

The resilience needed to survive everyday life amid structural and populist violence is not always credited, and there is a tendency to overlook, to use the words of Dorothy Roberts, “the subversive tactics of ordinary people” and focus only on the “spectacular feats such as those carried out by freedom fighters, demonstrators, or rioters.” Less glorified, but just as significant, are the everyday acts of resilience and survival undertaken by Black individuals faced with institutional racism and deprivation, documented, for example, by Makeda Silvera, Dionne Brand and Sylvia Hamilton.

Worldwide, we are currently in the midst of a revitalization of Black resistance, and by no means has Canada been exempt. Growing out of and building upon the community organizing traditions in the late 1980s of groups like the Black Action Defence Committee, protests by Black communities have erupted across Canadian cities in recent years. In addition to the everyday bravery of Black survival and care, there has been new life breathed into the Black radical imagination, spurring new forms of activism, art, intellectual work and resistance.

This resurgence is taking place not only in the United States, but also in regions less well known for their Black populations, including solidarity actions in Palestine and Black organizing in numerous nations across Latin America. Conversations across Black communities around the world are rendering it clear that anti-Blackness knows no borders: few, if any, places in the world have been untouched by the legacies of European colonization and slavery, or the racist worldviews left in their wake.

Contemporary movements for the dignity of Black lives are underway throughout the African diaspora, many, but certainly not all, under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter. At the same time, the unique realities of anti-Black racism as it has evolved locally across different regions are also being widely shared and disseminated.

As a Black activist and writer, I situate myself and my writing within the growing movement that fights for Black lives and against state violence. This book describes, in sometimes painstaking detail, the structural conditions that mandate ongoing Black suffering in Canada, as it is my hope that in recognizing our conditions, we will be better placed to challenge them.

For that reason, though this book is for everyone with an interest in Black lives in Canada, it is written most particularly for those who are committed to working toward an affirmation of Black resilience, Black life and Black humanity.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/the-struggle-against-anti-blackness-in-canada/