Scenes of destruction in Cizre after a weeks-long military siege. Photo: Rebecca Harms

Silencing dissent: Turkey’s crackdown on press freedom

- March 17, 2016

Authority & Abolition

As Turkey’s assault on the Kurds escalates into full-blown civil war, the increasingly despotic Erdoğan steps up his crackdown on the freedom of speech.

- Authors

Freedom of speech in Turkey is deteriorating at a rate of knots. This week, a British academic was deported from the country with no trial and three academics were arrested, all accused of disseminating terrorist material. Earlier this month, Zaman — a widely-read newspaper critical of the regime — was seized and placed under control of a board of trustees by an Istanbul court.

Index on Censorship has recorded more than ten press freedom violations over the past month alone, and 203 verified violations since May 2014. Along with the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders, they have been mapping violations of press freedom over the last two years. Their findings make uncomfortable reading. In 2015, Turkey was ranked 149th out of 180 countries in the press freedom index.

Social media censorship

It is not only in the mainstream media where the Turkish authorities are able to clamp down on freedom of expression. Turkey’s leverage over social media is an open secret. During the Gezi Park uprising in 2013, Erdogan was famously recorded saying that “To me, social media is the worst menace to society.” The regime was then able to briefly ban Twitter and YouTube in March 2014, though the two websites have been less supine than Facebook, who seem to be implementing the government’s demands for censorship with no complaint.

Thanks to the work of a poorly-paid employee of a company to whom Facebook outsources its content moderation, we know the degree to which Facebook has acquiesced to the Turkish government’s censorship requirements. The document instructing Facebook’s moderators on the banning of illicit content specifically forbids posts with the following: attacks on Ataturk, maps of Kurdistan, burning of Turkish flags, PKK support, and Öcalan-related content. The only other restricted content in this section of international compliance relates to Holocaust denial.

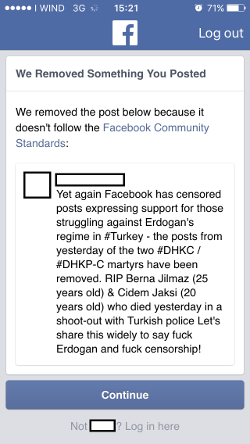

Incredibly, this policy is implemented internationally. Editors of a popular Facebook news page with almost 200,000 followers called World Riots recently fell foul of Facebook’s “community standards”. On Sunday March 6, they were informed that a post that had been made a few days earlier had been removed and that the editor (based in Italy and the UK) who posted it would have their account suspended for 24 hours, threatening permanent deletion of both the private account and page.

The post in question referred to some photos that had been shared from another page called Yasasin Halkin Adaleti on Thursday March 3, and had mysteriously disappeared within a few hours, depicting two female communist militants of the DHKP-C who had been killed in a shoot-out with Turkish police in Istanbul.

The photos of the two women were re-posted directly by World Riots with the following caption: “Yet again Facebook has censored posts expressing support for those struggling against #Erdogan’s regime in #Turkey — the posts from yesterday of the two #DHKC/#DHKP-C martyrs have been removed. RIP Berna Jilmaz (25 years old) & Cidem Jaksi (20 years old) who died yesterday in a shoot-out with Turkish police. Let’s share this widely to say fuck Erdogan and fuck censorship!”

The photos of the two women were re-posted directly by World Riots with the following caption: “Yet again Facebook has censored posts expressing support for those struggling against #Erdogan’s regime in #Turkey — the posts from yesterday of the two #DHKC/#DHKP-C martyrs have been removed. RIP Berna Jilmaz (25 years old) & Cidem Jaksi (20 years old) who died yesterday in a shoot-out with Turkish police. Let’s share this widely to say fuck Erdogan and fuck censorship!”

Although censoring a post explicitly about censorship is a particularly blatant transgression of the norms of freedom of expression, it wasn’t surprising. In August 2015, another editor of World Riots had posted a meme depicting Erdogan in the attire of an ISIS executioner, which was then removed by Facebook with a similar warning. The political content of this post was a clear comparison between the murderous regime in Turkey and the brutality of ISIS, as well as a comment on the unspoken financial and military support Erdogan’s regime is providing them.

Clearly the Facebook content moderators have World Riots in their sights now. For the second time in a week, the same editor was informed that a post was removed and that their account was again suspended, this time for three days. The offending post was a photo that had been posted months ago, no later than November 2015, which, given the number of posts made to the page (on average around 3 per day) would entail scrolling a long way through to find.

The photo is of a famous mural in Bologna, Italy, depicting a woman at the heart of Kurdish flags with the words “Kobane Resiste” (Kobane resists), extending solidarity with a city that has become a symbol of anti-fascist, anti-imperialist resistance across Europe. There is no military regalia in the image, nor reference to the PKK or YPG/J in the post — the only possibly offensive elements being flags in the Kurdish colours of yellow, green and red, some red stars and the notion of the Kurdish city of Kobane resisting.

The photo is of a famous mural in Bologna, Italy, depicting a woman at the heart of Kurdish flags with the words “Kobane Resiste” (Kobane resists), extending solidarity with a city that has become a symbol of anti-fascist, anti-imperialist resistance across Europe. There is no military regalia in the image, nor reference to the PKK or YPG/J in the post — the only possibly offensive elements being flags in the Kurdish colours of yellow, green and red, some red stars and the notion of the Kurdish city of Kobane resisting.

World Riots does not shy away from contentious political claims involving subversive and potentially offensive imagery. A crucial part of its ethos and reason behind its popularity is its stance against censorship, aiming to post news stories that are often neglected by the mainstream media. One recent example of such a post that was shared on World Riots, of a Swastika swinging like a pendulum over the face of Donald Trump to reveal Adolf Hitler beneath, went viral, reaching almost a quarter of a million people.

As of yet, this has not been censored by Facebook, despite the parallel comparison of Erdogan-ISIS and Trump-Hitler. Why the double standards when it comes to Turkish politics? Why in particular has the censorship seemingly been ramped up now, at a time of political sensitivity between the EU member states and Turkey?

Escalation of attacks on the media

This heightened sensitivity displayed by Facebook — deleting a photo of a piece of graffiti — is just one element in a worrying escalation in Turkey’s ability to clamp down on free speech with the protection from international condemnation of EU and NATO friendship.

Reporters Without Borders secretary-general Christophe Deloire commented in relation to last week’s takeover of Zaman: “It is absolutely illegitimate and intolerable that Erdoğan has used the judicial system to take control of a great newspaper in order to eliminate the Gülen community’s political base. This ideological and unlawful operation shows how Erdoğan is now moving from authoritarianism to all-out despotism.”

In a clear sign of this increasing despotism, simply insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has led to prosecution and imprisonment. In Amnesty International’s annual report on Turkey they state:

In the six months to March, the Minister of Justice gave permission for 105 criminal prosecutions for insulting President Erdoğan under Article 299 of the Penal Code. Eight people were remanded in pre-trial detention. […] In September, a 17-year-old student was convicted of “insult” for calling the President ‘the thieving owner of the illegal palace’. He received a suspended sentence of 11 months and 20 days by a children’s court in the central Anatolian city of Konya.

According to the same report, Cumhuriyet newspaper journalist Canan Coşkun faces up to 23 years and four months in prison for insulting state prosecutors in her investigation into corruption.

Remarkably for those following cases of collusion between the Turkish regime and Islamist groups, two of the newspaper’s senior staff have been charged with “espionage, revealing state secrets and assisting a terrorist organization” after alleging that the Turkish intelligence services transferred weapons to an armed group in Syria in 2014 (Erdoğan originally claimed the trucks were delivering humanitarian aid). More recently for the same “crime” of insulting the President, Bans Ince, the former editor of the left-leaning Birgün newspaper, was sentenced to 21 months in prison.

Censorship and the war on Kurds

For Erdoğan’s regime, limiting the spread of information about the bloody war it is conducting against the Kurdish people and the revolutionary leftist organizations is a keystone of its military strategy. Too much information about its bloody ethnic cleansing in the area could spark even more protests all over Europe, where more than 1.5 million Kurds live.

Given the popularity of the left-wing, pro-Kurdish HDP, the negative attention drawn to Erdoğan’s regime by 2013’s Gezi Park protests, and the role of traditional and new media in both phenomena, media manipulation is a crucial component of Turkey’s domestic policies of repressing internal dissent.

During the 79-day-long curfew imposed since December 14 on the Kurdish city of Cizre, a town of 132,000 near the banks of the Tigris river and the borders of Syria and Iraq, the Turkish army claims to have killed more than 700 Kurdish militants — widely believed to be a highly exaggerated number. Furthermore, 92 civilians were killed, according to human rights groups, and since hostilities ended another 171 bodies were found.

Turkey launched its military operation in the southeastern part of the country in July 2015, breaking a ceasefire signed with the PKK in 2013. Turkish security forces entered a number of Kurdish settlements in armored vehicles to take on the Kurdish movement. Hundreds of Kurdish militants were killed since then. At the same time, Amnesty International reported that at least 150 civilians, including women and children, were killed, and that over 200,000 lives had been put at risk.

Erdoğan’s war against the Kurdish people is not only carried out by the Turkish army and in Turkish Kurdistan, but is also conducted with the use of the Turkish-backed Islamist groups both in Turkey and Syria. The images of the bomb attacks of Suruc and Ankara are still vivid in our memory.

On July 20, 2015, 33 people were killed in a suicide attack attributed to IS. The victims were mainly members of the pro-Kurdish leftist youth giving a press conference on their planned trip to help reconstruct Kobane after its fierce resistance against the IS siege.

On October 10, 2015, another suicide attack hit the pro-Kurdish left movement, during a peace rally organized by leftist groups and political parties outside Ankara Central railway station. The death toll reached 102 and more than 400 people were injured. The brother of the Suruc attack was identified as the bomber; both were suspected to be linked to IS-affiliated groups. Due to the size of the city, and the high level of securitization, it seems unlikely that the attack could have happened without at least the knowledge of the Turkish security services.

The Turkish regime’s connections with Islamist groups active in the Syrian conflict have been well established. To look for the latest allegations of this lethal collaboration, we don’t have to go back far in time. In an interview with RT published last week, a spokesman for the Kurdish YPG militia accused Turkey of providing a clear transit route for the chemical weapons that were deployed against them near the city of Aleppo: “All signs point to the fact that these factions were using banned weapons (sarin gas, a.n.), but we cannot access the launching area, as it is located on the front between the Turkish and rebel forces,” the YPG militant told RT from Rojava in Syria.

Turkey’s geopolitical position

There is little need to wonder why Erdoğan’s regime is conducting this all-out war against the Kurdish people. Their movement and the pro-Kurdish left represent an existential threat to Erdoğan’s regime and the political and social alliance which has supported his rise to power, not only providing a vessel for strong political and social opposition both inside and beyond the national borders, but also contributing to create instability, which financial markets particularly dislike when it affects emerging economies. Turkish growth is stagnating, while the Turkish lira is in freefall against the dollar and Russian sanctions are hitting Turkish industrial and agricultural production hard.

Facing the current deadlock in his almost 20-year-long regime, Erdoğan’s strategy is appropriately summed up by a former politician for the opposition party CHP: “It is as if Erdoğan is saying: If you vote for me, I will bring peace and stability. If you don’t, I will make your life a living hell.”

Whilst the Kurdish diaspora and international alliances are a potential sticking point for the regime’s international clout, Turkey’s geopolitical position has developed over the last year due to the EU’s desire to strengthen its external borders. Turkey represents a key ally for the EU, absorbing migrants displaced by the civil war in Syria and enforcing harsh border controls. The impetus for strengthening such an alliance, becoming more and more urgent since the peak of last summer’s refugees crisis, has coincided with Turkey’s increasing repression with impunity.

On the timing of the state’s takeover of the Zaman newspaper, when EU officials and heads of state were on official visits, Mapping Media Freedom commented:

Turkey now calibrates its place in the world not as a democratic standard bearer in a troubled part of the globe but as a buffer zone between Fortress Europe and a tide of Syrian refugees. This, it believes, gives it licence to get away with the murder of a newspaper.

The gravity of importance placed on Turkey as a way to repel refugees from the European continent has allowed it to shed any semblance of free expression, whilst the European Union is on the verge of crossing Erdoğan’s palm with €6 billion worth of silver. As long as European politicians prioritize their electoral aspirations over the rights of political dissidents in Turkey, constraints on freedom of speech, both in Turkey and abroad, will only increase.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/turkey-censorhip-kurdish-conflict/