The New Scramble

Over a century after the original Scramble for Africa, European leaders are today imposing new forms of colonialism on the continent in the shape of militarized border controls.

The Rise of Border Imperialism

- Issue #8

- Authors

In 1891, the French economist Paul Leroy Beaulieu fiercely defended European colonialism in Africa, saying: “This state of the world implies for the civilized people a right of intervention … in the affairs of [barbarian tribes or savages].”

Beaulieu’s defense came in the midst of the European carve-up of Africa cemented in the 1885 Berlin agreement. As it has now been five decades since most African liberation movements won independence, it might therefore seem a surprise to read a European ambassador in May 2018 declaring that “Niger is now the southern border of Europe.” Two thousand miles to the east, the ambassador’s comments were echoed by a Sudanese border patrol agent, Lieutenant Salih Omar, interviewed by the New York Times, who referred to the Sudan-Eritrean border as “Europe’s southern border.”

There has long been an argument, prominently articulated by Ghanaian freedom-fighter Kwame Nkrumah, that European control of Africa’s destiny never ended with colonialism. These cogent arguments largely focused on the way debt, trade and aid have been used to structure the continued dependence of Africa’s newly independent states on Europe. The consensus, however, by both a European ambassador and a Sudanese border patrol guard that Europe’s border is not in the Mediterranean but lies as far away as Sudan and Niger, suggests that European territorial control of Africa has not really ended either.

Migration Control at Heart of EU Foreign Policy

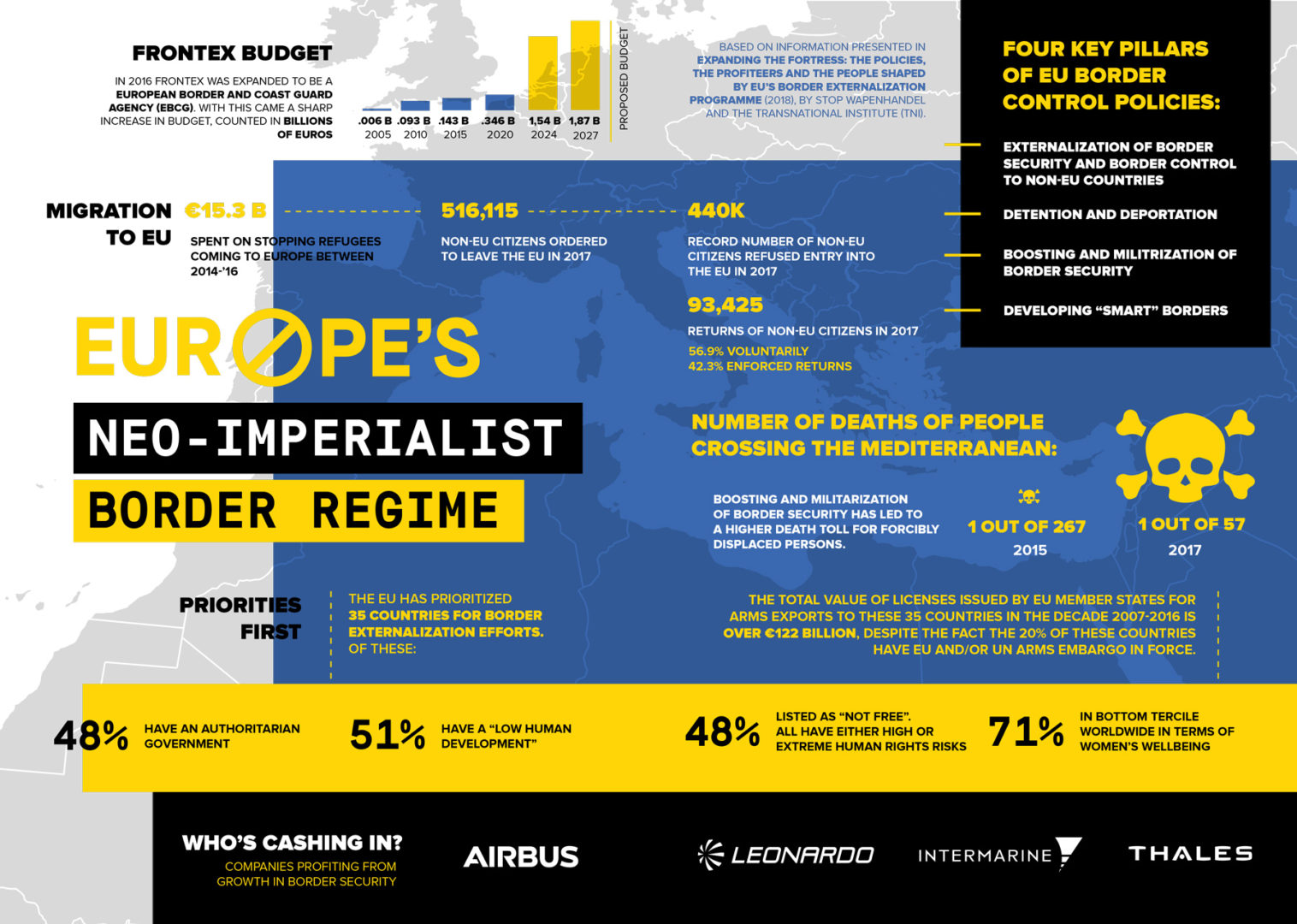

The reason for this European re-engagement with African territory — and not just political and economic dominance — has been largely due to one factor: a desire to control migration. The rise in the number of refugees fleeing to Europe, particularly after the Syrian civil war, pushed migration high up the political agenda, releasing significant resources for border control. Europe’s Coastguard and Border Agency Frontex has seen an incredible 5,233 percent rise in funding since 2005 (from €6 million to €320 million in 2018). Borders have been militarized in Eastern Europe and border guards deployed across Europe from Calais to Lesvos.

Less well known is that it has also led the EU to put migration control at the heart of its international policies and its relations with third countries, insisting on border control agreements with more than 35 neighboring nations to control migration, labelled in Commission-speak as “border externalization”. These agreements require signatory nations to accept deported migrants from Europe, to increase border controls and staff on borders, introduce new biometric identity and passport systems to monitor migrants, as well as to build detention camps to detain refugees.

The rationale given by the EU is that this will prevent the deaths of refugees, but a more likely reason is that it wants to make sure that refugees are stopped long before they get to European shores. This satisfies both the hostile racist politicians in Europe as well as those seemingly more liberal politicians unwilling to confront whipped-up anti-immigrant sentiment, who want the crisis out of sight, out of mind. Germany, for example, with a relatively progressive record of welcoming refugees (at least in the summer of 2015), is also one of the main funders of border externalization, happily signing agreements with dictators like Sisi in Egypt to prevent refugees heading to Europe.

The evidence suggests these agreements may have served the EU’s ultimate purpose of decreasing numbers entering Europe, but it certainly has not increased refugees’ safety and security. Most studies show that it has forced refugees to seek more dangerous routes and rely on ever more unscrupulous traffickers. The proportion of recorded deaths to arrivals on Mediterranean routes to Europe in 2017 was over five times as high in 2017 as it was in 2015. Many more deaths at sea and in deserts in North Africa are never recorded.

The evidence suggests these agreements may have served the EU’s ultimate purpose of decreasing numbers entering Europe, but it certainly has not increased refugees’ safety and security. Most studies show that it has forced refugees to seek more dangerous routes and rely on ever more unscrupulous traffickers. The proportion of recorded deaths to arrivals on Mediterranean routes to Europe in 2017 was over five times as high in 2017 as it was in 2015. Many more deaths at sea and in deserts in North Africa are never recorded.

As a new report by the Transnational Institute and Stop Wapenhandel reveals, it has also led the European Union to embrace authoritarian regimes — and worse, provide equipment and funding to repressive police and security forces — while diverting necessary resources from investments in health, education and jobs.

Dirty Deals with Dictators

Niger, a major transit country for refugees, has become the biggest per capita recipient of EU aid in the world. This is partly because it is one of the world’s poorest countries, but it is also prioritized because it is a gateway for many refugees heading to Europe. There seem to be no limits to resources available for border infrastructure, yet the World Food Program, which supports almost a tenth of Niger’s population, has received only 34 per cent of the funding it needs for 2018. Meanwhile, under European pressure, the strengthening of border security has destroyed the migration-based economy in the Agadez region, threatening the fragile internal stability in the country.

The EU’s dependence on cooperation with the Nigerien government has also emboldened the country’s autocratic leaders. A protest against increased food prices by Nigeriens in March 2018, for example, led to the arrests of its main organizers. Refugees travelling through Niger report increased human rights abuses and are forced to take greater risks to migrate. In one horrifying case in June 2016, the bodies of 34 refugees, including 20 children, were found in the Sahara desert, apparently left to die from thirst by smugglers.

Similarly in Sudan, the European Union maintains that it upholds international sanctions on the notorious Al-Bashir regime for its war crimes and repression, yet it has not faltered in signing border control agreements with Sudanese government agencies. This has included training and equipment for border police officers, even though Sudan’s borders are patrolled primarily by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which consist of former Janjaweed militia fighters used to fight internal dissent under the operational command of Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS). Human Rights Watch has “found that the RSF committed a wide range of horrific abuses, including … torture, extrajudicial killings and mass rapes.” The German government agency GIZ says it is aware of the risks of cooperation, but nevertheless considers it “necessary” to include them in capacity development measures.

Europe’s involvement in Sudan and Niger underscores author and activist Harsha Walia’s argument in her book, Undoing Border Imperialism, that border control measures are a form of imperialism because they include displacement, criminalization, racialized hierarchies and the exploitation of people. It is noticeable in terms of historical echoes for EU border imperialism that while the Scramble for Africa was largely defended by its colonial apologists for its potential to civilize the “barbarians” at Europe’s gates, the focus this time seems to be only about keeping the “barbarians” from passing through Europe’s gates.

In even more disturbing historical parallels, it is shocking to note that while the 1885 Berlin Agreement stipulated that Africa “may not serve as a market or means of transit for the trade in slaves, of whatever race they may be,” the EU’s collaboration with Libyan militia has actually led to a revival of the slave trade, with refugees being sold as slaves captured on CNN in late 2017.

Borders Equal Violence

We should not ultimately be surprised. As journalist Dawn Paley has noted, “far from preventing violence, the border is in fact the reason it occurs.” Borders are walls that seek to block out a gross inequality between Africa and Europe constructed during colonialism and perpetuated by European economic and political policies today. Ultimately this violence is felt on the body, the border marking its scars across the flesh of people. It is felt in the torn skin of those who daily try to cross the fortified fences of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco. It is felt in the violated bodies of women raped and abused by smugglers and border guards. It is there in the many undiscovered skeletons in North African deserts and the Mediterranean Sea.

This border imperialism is not an exclusive European phenomenon. It can be found in Mexico’s Programa Frontera Sur, started in 2014 under pressure from the United States, to strengthen border security on its border with Guatemala. Like its European equivalents, it has also resulted in more repression and violence against refugees, increased detention and deportations and the forcing of refugees towards more dangerous migration routes and into the hands of criminal smuggle networks.

Perhaps the most well-known example of border externalization are Australia’s offshore detention centers on the islands of Nauru and, until ruled illegal last year, in Manus (Papua New Guinea). All migrants trying to go to Australia by sea are transported to these centers, which are run by private contractors, and kept there for long periods. If the detained refugees are granted asylum status, they are resettled in third countries. This policy is accompanied by “Operation Sovereign Borders”, a military maritime operation to force or tow refugee boats back to international waters.

There have been many cases of human rights violations in Australia’s offshore detention centers. Yet many European leaders have embraced the Australian model, increasingly arguing for the EU to put refugees in “processing camps” in North African countries, building on the current policy of turning Europe’s neighbors into its new border guards. Europe enthusiastically embraces the Australian approach of building camps in remote places, which, as human rights lawyer Daniel Webb notes, serve “to hide from view what they don’t want the public to see — deliberate cruelty to innocent human beings.”

Corporate Winners

While the similarities between these examples of border externalization are undeniable, only in Europe do they explicitly connect the policies to old colonial relations. At the launch of the Partnership Framework on Migration, the overall framework for cooperation on migration with third countries, in June 2016, the European Commission noted that “the special relationships that member states may have with third countries, reflecting political, historic and cultural ties fostered through decades of contacts, should also be exploited to the full for the benefit of the EU.” It also unequivocally praised the opportunity the agreement provided for European business, arguing that “private investors looking for new investment opportunities in emerging markets” must play a much greater role instead of “traditional development co-operation models.”

This points us towards the private interests benefiting from these border externalization policies: the military and security industries providing the equipment and services to implement strengthened and militarized border security and control in third countries. A plethora of firms have thrived in this expanding market, but prominent among them are European arms giants such as Airbus (Paneuropean), Thales (France) and Leonardo (Italy — formerly named Finmeccanica).

These are not just the casual winners of EU policies; they are also the driving forces behind them. They have both set the general discourse — framing migration as a security threat, to be combated by military means — as well as put forward concrete proposals, such as the creation of the EU surveillance “system of systems” EUROSUR and the expansion of Frontex, which through successful lobbying have been turned into official EU policies and new institutions.

These firms then can reap the rewards by promoting their own services and products, helped along by their constant interaction with EU policymakers. This encompasses regular meetings with officials at the European Commission and Frontex, participation in official advisory bodies, the issuing of influential advisory papers, participation in security fairs and conferences, and more. While the main focus has been on militarizing the EU external borders, companies increasingly eye the African border security market as well. Hence they are also lobbying for EU funding for border security purchases of third countries.

This strategy has paid off handsomely. Strengthening the global competitiveness of the European military and security industry has now become a stated objective of the EU. The Commission plans for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), the EU budget for 2021-2027, propose to almost triple spending on migration control. Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, EU member states and third countries will all get more money to spend on strengthening border security, including the purchase of military and security equipment and services.

Rendering Resistance Visible

While specific horrific situations, such as the migrant slave markets in Libya or a particular drowning incident in the Mediterranean, sometimes cause outrage and opposition, it is hard to see a change in the general European emphasis on “bringing down the numbers” of people willing to make the crossing. This is even more challenging when EU border militarization is outsourced to and hence rendered largely invisible in countries far from Europe.

EU policies need to be fought at a number of levels, both inside the EU and in third countries. This means that we do not only need to act against the most obvious manifestations of these policies — in terms of border control and the detention and deportations of refugees — but also against the private interests behind these policies. We have to unmask the commercial, industrial forces that are currently profiting from Europe’s border imperialism, as well as the media outlets and political parties that have manipulated public opinion by targeting refugees as scapegoats for the consequences of austerity policies.

More systemically, confronting border colonialism requires addressing Western responsibility at large, eliminating the reasons people are forced to flee in the first place, and resisting those policies and stakeholders in Western countries that are causing them: EU support for authoritarian rulers, the companies causing climate change, unjust trade relations, corporate impunity, reckless military interventions and the arms trade. And it means true decolonization, ending the continued European grip on its former colonies, and working towards a fundamental shift in the international order. This will become even more important in the context of worsening climate change, when migration, even if largely internal, will be a necessary form of adaptation.

It will also require increased solidarity and cooperation with movements and organizations in the third countries affected, in horizontal forms of collaboration. This could include support for migrant-led movements emerging in many countries, for communities that host large numbers of (stranded) refugees, direct humanitarian efforts such as the search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean, as well as for organizations advocating for human rights for migrants. But it could also include groups and movements fighting for democratization, against authoritarian regimes, against extractive industries, and those seeking a livelihood for everyone, against violence and Western domination.

Unravelling the legacy of colonialist violence will not be easy. While the European Union is divided on many issues, the consensus around border security is strong. The great decolonial thinker Frantz Fanon realized how colonialism colonized not just territory and the body but also the mind. As he wrote in Black Skin, White Masks:

In order to terminate this neurotic situation, in which I am compelled to choose an unhealthy, conflictual solution, fed on fantasies, hostile, inhuman in short, I have only one solution: to rise above this absurd drama that others have staged around me, to reject the two terms that are equally unacceptable, and through one human being, to reach out for the universal.

It is a yearning for a universal humanity reflected in slogans that “no human is illegal” — the only true basis for an end to the violence of border imperialism.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/border-imperialism-europe-africa/

Next Magazine article

Africa’s Place in the Radical Imagination

- Zoé Samudzi

- September 26, 2018

Beyond the Border Kaleidoscope

- Natasha King

- September 26, 2018