the new normal

Capitalist realism is over. Europe’s response to COVID-19 and the climate crisis shows that a new form of capitalism is in the making.

Capitalist Catastrophism

- Issue #10

- Author

Is Mark Fisher’s “capitalist realism” this generation’s “end of history thesis”? For nearly thirty years Francis Fukuyama’s contention that “Western liberal democracy” represents “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution” has measured the ebb and flow of history. The collapse of the World Trade Center; the Iraq and Afghanistan wars; the 2008 financial crisis, the rise of ISIS, the climate crisis and now the coronavirus have each prompted op-eds testing the thesis and finding it confirmed or wanting.

In 2017 even Fukuyama had a go at becoming an anti-Fukuyamist when he voiced concern for the future of Western democracy, later going as far as to say that socialism “ought to come back” — if only to save capitalism from itself.

Since 2009, when Fisher first defined capitalist realism as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible to even imagine a coherent alternative to it,” his theory has inspired similar periodizations.

Already in 2012 Paul Mason was convinced that the era capitalist realism was over. Carried away by the excitement of the Arab Spring and Occupy movements, Mason believed that capitalism’s hold on reality was broken and that a new, networked and democratic future was in the making.

Fisher disagreed. Capitalist realism, he explained, was more pernicious than Mason realized. Many of those who consciously oppose capitalism have often unconsciously accepted it as the unalterable backdrop to their anti-capitalism. From this perspective the Arab Spring and Occupy Movement look exactly how we should expect capitalist realist protests to look. Both struggles knew what they were against but they were incapable of articulating a vision of the future that broke with the capitalist horizon. Their demands, if they made any at all, were for an extension of bourgeois democracy and for a more equal distribution of capitalism’s ill-gotten gains. Capitalist realism, in other words, persisted.

In January 2019, Micah Uetrict proposed a different end date, the ascent of Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, he wrote, could “finally spell the beginning of the end of capitalist realism.” After decades of unremitting neoliberalism the popularity of these figures suggested that it was not only possible to imagine the end of capitalism but that movements were ready and willing to fight for it. More than this, unlike the Occupy movement before it, this new sequence of struggles had developed a set of demands and policies that took aim at some of the essential aspects of global capitalism: the exploitation of nature, the length of the working week, racialized and gendered oppression, and ownership of at least some of the means of production. As Keir Milburn, another advocate of this perspective wrote, the Corbyn moment had put a “crack in Capitalist Realism, a crack through which a flood of pent up postcapitalist desires have burst.”

Time has been no kinder to this argument than Mason’s. A little over a year later and the Corbyn and Sanders projects are defeated, a pandemic is tearing its way through the world’s population and tens of millions are unemployed across the US and Europe. According to the International Monetary Fund the global economy will face its worst recession since the Great Depression. In Europe, where even before the pandemic Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio was at 134 percent and Spain’s and France’s were nearing 100 percent, there are warnings of a sovereign debt crisis that could pose an existential threat to the European Union. Meanwhile, the newly “independent” UK, where I live, is forecast to see its economy shrink by 14 percent in 2020, its deepest recession on record. On top of all of this the climate crisis rages on unaddressed and unabated.

It is possible to interpret the global response to this sequence of events as a vicious reassertion of capitalist realism. After a brief respite where it seemed that another world was possible, we have been thrown forcefully back into this world, a world where capital reigns supreme, where it is not inconceivable to let people die so that capitalism might live and where we must bail out private companies with public money. This is a world in which Rishi Sunak’s “whatever it takes” is the new “there is no alternative” and where even supposed leftists — to turn once more to Mason — are incapable of imagining a solution to the crisis more ambitious than raising taxes and “making future generations pay.”

For all the left’s talk of how the virus is “re-writing our imaginations” so that “what felt impossible has become thinkable,” a devastating global pandemic has failed to make the case for universal healthcare in the US or the value of so-called “unskilled labor” in the UK, let alone the abolition of capital. Capitalist realism, it seems, persists.

Against this interpretation I want to suggest that we are not really in capitalist realism anymore, that we have in fact been leaving it for quite some time and that the signs of what might replace it in our pandemic-ridden and rapidly warming world are increasingly apparent. Unless there is a radical break from capitalism — a revolution — what will supplant capitalist realism is not the ability to imagine and fight for a post-capitalist future as Mason, Uetricht and Milburn had hoped, but something more ambiguous and perhaps ultimately worse. I call this something worse “capitalist catastrophism.”

Capitalist catastrophism is what happens when capitalist realism begins to fray at the edges. It describes a situation in which capitalism can no longer determine what it means to be “realistic,” not because of the force of movements assembled against it but because capital’s self-undermining and ecologically destructive dynamics have outstripped capitalism’s powers to control them.

Unlike capitalist realism capitalist catastrophism is not a coherent social formation but rather the unmaking of one. It is the unravelling of capitalist realism that the “catastrophic convergence,” to borrow Christian Parenti’s phrase, of climate breakdown, a global pandemic and the persistent violence wrought by capital on the poor and working class has brought into view.

From Capitalist Realism to Capitalist Catastrophism

Capitalist realism had three essential features. First, that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism; second, that the future was cancelled; and third, that the capitalist realist condition was a class project in need of constant reinforcement by the bourgeoisie. Under capitalist catastrophism these features do not so much disappear as mutate and adopt new forms.

-

It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism

Fisher claimed that Frederic Jameson’s oft-misattributed aphorism that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism “captured precisely” what he meant by capitalist realism. But this self-assessment is not entirely accurate. While for Jameson the aphorism pointed rather narrowly to the atrophying of our imaginations under what he calls “late capitalism,” for Fisher it pointed to a more expansive, near pervasive, ideological and affective atmosphere. Capitalist realism was something that we did as much as something that was done to us, it was a “mood” on the left as much as a bourgeois ideology, a way of life as much as an institutional architecture, all of it converging to convince us that “there is no alternative” to capitalism.

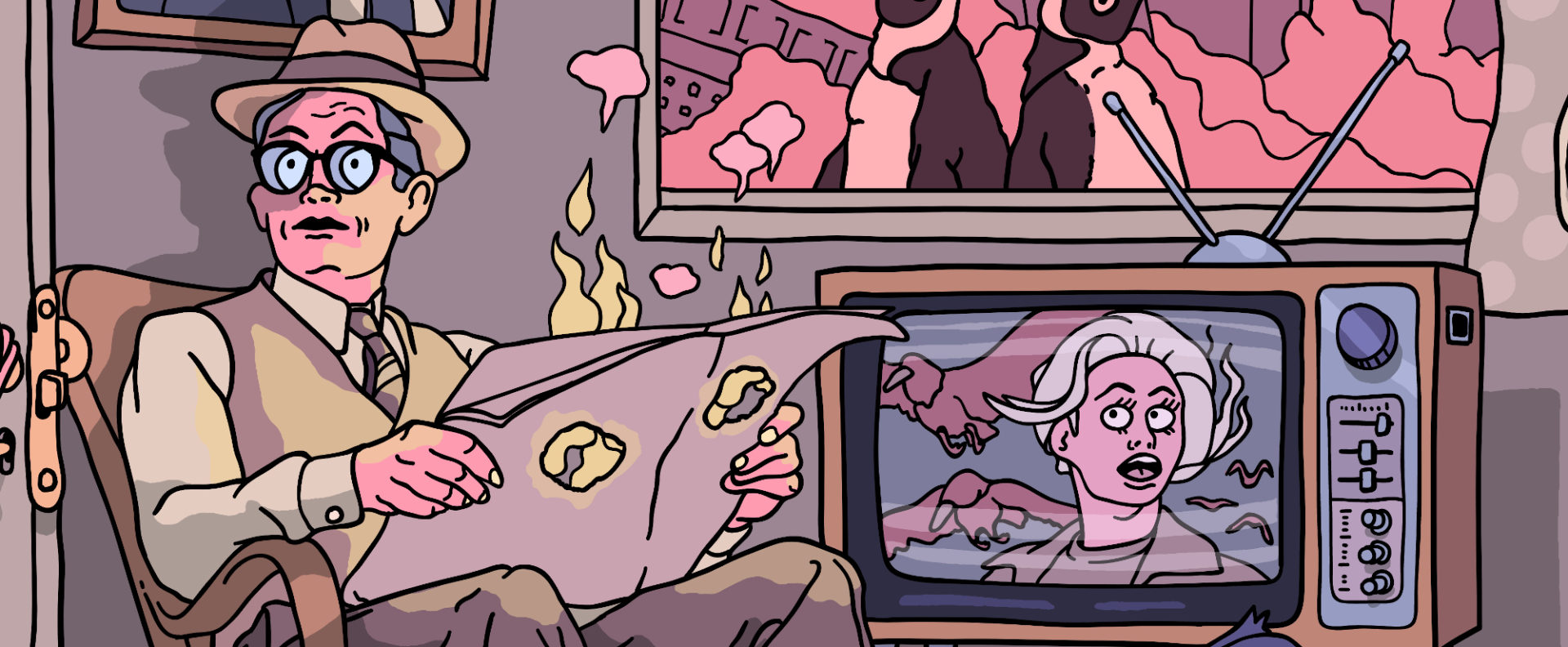

Under capitalist realism not only was it easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism but we enjoyed imagining the end of the world. Dystopic film and fiction proliferated: Armageddon, 2012, The Day After Tomorrow, Melancholia, Black Mirror, The Road and The Handmaid’s Tale, to name only a few, fed into the idea that however bad things were now they were at least not that bad. In Jameson’s words, capitalist realism encouraged a “nostalgia for the present,” an appreciation of our lot, and with this appreciation came a further withering away of our imaginations.

The end of the world might have passed for entertainment under capitalist realism but for us, now, it is all too real. Under capitalist catastrophism we no longer need to imagine the end of the world; we watch it in real time, we read about it on our social media feeds and we take to the streets to protest it. According to the International Panel on Climate Change the world’s governments have less than 10 years to respond to the crisis if we are to avoid more than 1.5C of global warming. By some estimates it is already too late. Already icecaps are melting at unprecedented and irreversible rates, already wildfires are roaring across California and Australia, already global soil fertility is in precipitous decline and already dwindling insect numbers are threatening a total “collapse of nature.”

Capitalist catastrophism names the period in which, as the climate scientist Valerie Mason-Delmotte puts it, “we can’t go back, whatever we do with our emissions.” From this point on the climate struggle is not just about “saving the environment,” as we used to be told, but about how much of it we will lose, how many of us will die, and how those who are left will adapt. Under capitalist catastrophism, in other words, the climate crisis becomes the primary vector of international class struggle.

Fisher thought that capitalist realism could only be toppled “if it is shown to be in some way inconsistent or untenable; if, that is to say, capitalism’s ostensible ‘realism’ turns out to be nothing of the sort.” Under capitalist catastrophism we are finally reaching this point. Austerity, escalating global inequalities and the imperialist core’s response to both the climate crisis and coronavirus have started to eat away at the fiction of capitalism’s compatibility with human and non-human flourishing. There is nothing “consistent” about destroying entire crops when there are mile-long lines for food banks, there is nothing “tenable” about the Bank of England bailing out the fossil fuel industry in the middle of a climate catastrophe and nothing “realistic” about the UK government’s strategy of herd immunity in response to coronavirus.

The increased visibility of capital’s cruel irrationality has given rise to one of the clearest signs that we are not in capitalist realism anymore: it is no longer easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. In just the past few years the left has assembled a profusion of post-capitalist imaginaries: transitional Green New Deals, degrowth futures, eco-modernist utopias, fully automated luxury communes, decolonized agroecological matrices, and even anti-authoritarian neo-feudalisms. Into this mix we must now add a new sub-genre of COVID-19 inspired post-pandemic, post-capitalist lifeworlds.

In many ways the left’s prodigious power of imagination today is reminiscent of the period of 17th and 18th century utopianism that was in equal parts praised and lambasted by Marx and Engels. For the writers of The Communist Manifesto, at a point in capital’s early development, when the proletariat was “still in a very undeveloped state,” the “fantastic pictures” and utopian musings of thinkers such as Charles Fourier, Henri de Saint-Simon and Étienne Cabet indicated “the first instinctive yearnings of that class for a general reconstruction of society.”

It could be that after decades of capitalist realism the authors of today’s speculative futures are beginning to play a similar role. But if this is the case we should remember that for Marx and Engels the yawning gap between the utopian’s idyllic visions and the definite social relations that confronted the working class made their work of only limited use to the revolutionary movements of their day. As the proletariat became conscious of itself as a class waging a war against their bosses and the state, the utopians clung to the hope that their hyper-rationalized blueprints for the future would cut across class lines. “For how can people, when once they understand their system, fail to see in it the best possible state of society?,” Marx and Engels asked ironically.

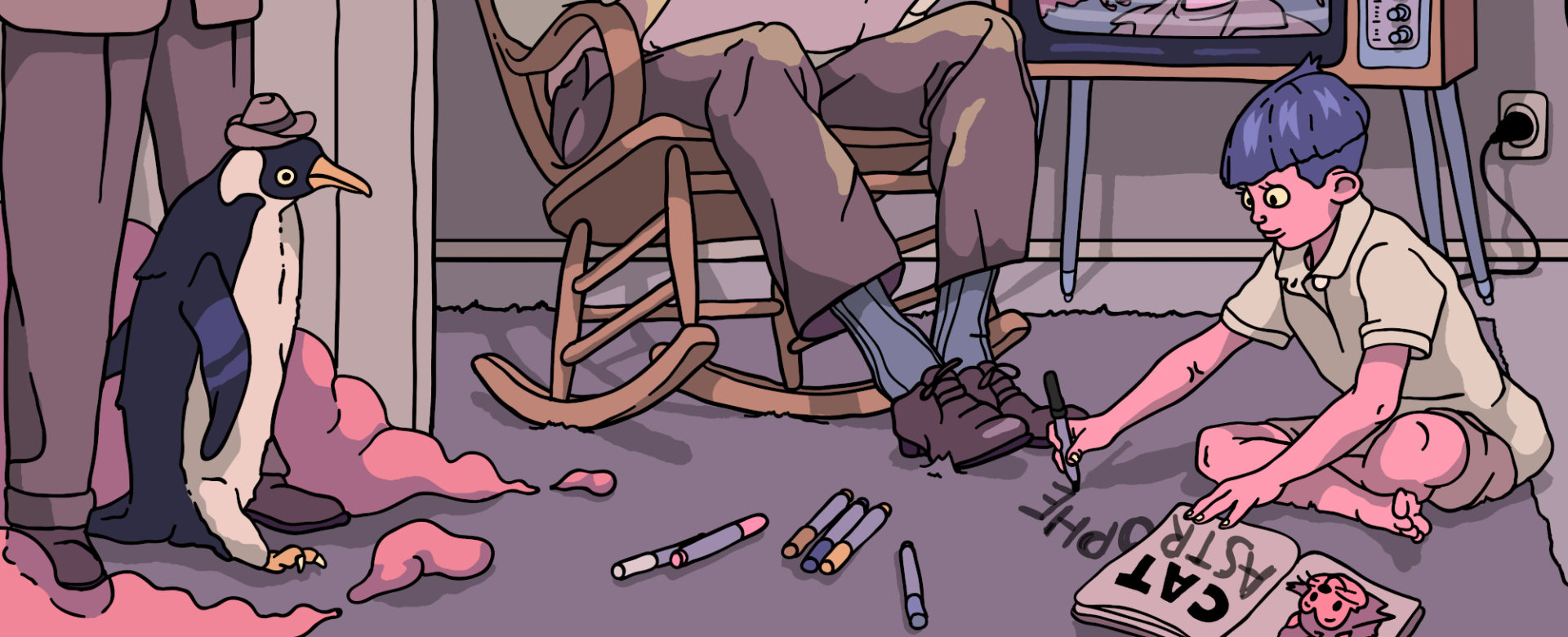

There is a risk that today’s utopias are being written in a similarly unreflective way by those whose job it is to publish radical books with radical publishers. All the while class struggles are being fought over issues that will make material, albeit limited, differences to the lives of the working class: COVID-19 mutual aid groups, community and workplace unions, climate strikes, migrant solidarity networks, food sovereignty initiatives and police accountability boards. If the contemplations of today’s utopians play any role at all in these struggles it is only in the most tangential of ways.

This is not to say that it is wrong for those of us who can to busy ourselves with post-capitalist imaginaries; it is to say that our capacity to do so implies that we are at a specific stage in our struggle’s development. After decades of capitalist realism we are once again learning to flex our utopian imaginations. We have become skilled time travellers, projecting our ideals into far-flung futures untroubled by the vicissitudes of the present. We have broken with capitalist realism.

But no sooner is one contradiction overcome than we encounter another. Under capitalist realism we were incapable of imagining a world after capitalism. Under capitalist catastrophism this is no longer the problem. Instead, the gap between what we can conjure in our minds eye and our concrete conditions of struggle can appear formidable, even insurmountable. We find ourselves caught between what is imminently “winnable” in the here and now and where, with ever increasing urgency, we know that we need to be.

What is “winnable” today is bound by the strictures of capitalist realism, of what we know is “realistic” within the capitalist horizon. What is imaginable breaks free from these strictures only to bound off into the distant future leaving few tracks to follow. What we lack under capitalist catastrophism is a theory and a practice of transition that breaks with our habituated patterns of thought and practice to bridge the gap between the present and the future. As the Marxist psychoanalyst Paul Hogget puts it, what constrains us is not our inability to imagine the end of capitalism but “the lack of an idea of how even tomorrow might be different.”

-

The Future is Cancelled

When Fisher claimed that the future was cancelled he had in mind contemporary European culture’s inability to invent anything fundamentally new. Late capitalist culture, he thought, was moribund. Try as we might we are incapable of inventing new genres of music, new fashion trends, new cinematographic forms, or new literary genres. Instead, we recycle, we montage, we hybridize and we write unsatisfying sequels and reboots with alarming rapidity.

Under capitalist catastrophism it is still very much the case that the future is cancelled in this sense. But whereas Fisher saw the slow cancellation of the future as a primarily cultural phenomenon, today, it is increasingly political. And whereas for Fisher the cancellation of the future did not mean its literal cancellation, for many across the world today the future really is cancelled. The reason for this, quite simply, is Euro-American imperialism.

Capitalist catastrophism is characterized by crises — like the coronavirus and climate breakdown — that are not immediately economic in origin but nevertheless have the power to destroy business as usual. Mainstream economists, trained as they are in imperialist ideology, like to call such crises “exogenous.” These are events that are said to arrive from outside of the capitalist system “like an asteroid might hit earth.” They come “as a surprise,” “there is nothing we can do to precipitate [their] arrival” and they “can cause enormous damage.”

The distinction between exogenous and endogenous shocks has helped economists and bourgeois commentators to mystify the true causes of the pandemic. We are repeatedly told that unlike the 2008 financial crisis for which blame could be apportioned among “irresponsible” lenders and regulators, when it comes to the coronavirus “nobody’s to blame.” Rather, the pandemic is just “one of those unexpected challenges sent to test the human race and our modern connected society in so many ways we couldn’t have imagined.” It is “something like a natural disaster — a spontaneous, accidental eruption that’s no one’s fault.”

None of this is true.

For a start, the world’s governments have long been warned about a pandemic of this scale. In 1988 Nobel Laureate Joshua Lederberg explained that “the single biggest threat to man’s continued dominance on the planet is the virus,” in 2018 the World Health Organization released a report predicting the emergence of what it called “Disease X,” an unknown pathogen that would cause a “serious international epidemic” and in 2019 the UK government was told that the risk of a pandemic in the country was currently “very high.” Predictably, these warnings all fell on deaf ears.

More fundamentally, though, it is simply not the case that the coronavirus is exogenous to the capitalist economy. Though the precise geographical origins of COVID-19 are still to be determined, scientists agree that contrary to Trump’s racist ramblings the virus was not fabricated in a Chinese lab but originated in nature and before spilling over into human populations eking out a living in the informal economies on the edges of capital’s ecologically simplified supply chains.

The likelihood of such spill overs are exponentially increased by what Jason Moore calls capitalism’s “organization of nature,” that is, the way that capitalism tears into, degrades, exploits, recomposes and redistributes the natural world. Biologist Rob Wallace and his co-authors have demonstrated that there is a direct link between industrial agriculture’s circuits of accumulation and pandemics like the coronavirus. What passes for common practice in agribusiness — deforestation, the forced displacement of local populations, monocultures, genetic selection and the undercutting of local smallhold producers — creates near-perfect conditions for novel viruses to multiply and spill over into human populations.

This means that the pandemic is not just “one of those things.” It is about as much a product of global capitalism as the computer than I write on. Capital’s global circuits of accumulation have propelled the virus across planetary vectors, eased its passage across borders and facilitated its genetic mutation. Considering all of this it is no wonder that the pandemic’s true origins are routinely mystified. The coronavirus, like the climate crisis, is an argument against capitalism, an argument against the European model of development and “progress.”

In 1961 Fanon explained that Europe’s very way of life was “a scandal for it was built on the backs of slaves, it fed on the blood of slaves, and owes its very existence to the soil and subsoil of the undeveloped world.” In the colonial period this oppression took the form of immediate acts of violence wrought upon the minds and bodies of the subjugated.

After decolonization and in the neoliberal period that Fisher describes in his work on capitalist realism, the exploitation of the Third World took more mediated and subtle forms. As Utsa and Prabhat Patnaik show us, violence was no longer exercised through force but through the arbitrating power of the market. Wages in the Third World were deflated to protect the price of Western currencies while ensuring a constant flow of raw materials and food from the world’s poorest to the richest. This, it was claimed, was the only “realistic” way for the Third World to develop.

In contrast, our period of capitalist catastrophism is characterized by a return to immediate forms of subjugation. As the uneven and combined crises of the coronavirus and climate breakdown loosen capitalism’s hold on what it means to be realistic the imperialist core drops all pretense of “win-win” scenarios for the core and periphery to return to a strategy of social and ecological plunder. As Jodi Dean writes in her thesis on neofeudalism, this does not mean that mediated exploitation disappears but that “non-capitalist dimensions of production — expropriation, domination, and force — have become stronger to such an extent that it no longer makes sense to posit free and equal actors meeting in the labor market as even a governing fiction.”

The result today is a kind of “bio-apartheid” — an important precursor to the UN’s predicted “climate apartheid” — where the lives of European citizens, and the wealthy in particular, are once again and as always prioritized over the lives of those in the Third World.

For months now the US and Europe have been driving up the costs of crucial medical equipment while placing export controls on much-needed ventilators, face masks, gloves and gowns leaving the Third World without the supplies it needs to combat the spread of the virus. Meanwhile, the EU does nothing to help the plight of those who have contracted the virus in cramped refugee camps on its borders. For its part, in what the UK’s Ambassador to Egypt called “a great example of UK-Egypt cooperation,” the UK has bought large amounts of protective equipment from Egypt despite the country’s desperate shortage of equipment for its own doctors. When Egyptian workers took to social media to protest they were promptly silenced by their government, who know better than to put the interests of their own people before that of their largest investor.

Unable to feed themselves without super exploiting Eastern European labor, countries like the UK and Germany have loosened travel restrictions on seasonal labor from Europe’s internal peripheries. We know from the US that migrant agricultural workers cannot practice social distancing and are at an increased risk of contracting coronavirus.

And then we have the outrageously colonial ruminations of a French doctor broadcast on National television: “It may be provocative. Should we not do this [vaccination] study in Africa where there are no masks, no treatment or intensive care, a little bit like it’s been done for certain AIDS studies, where among prostitutes, we try things, because we know that they are highly exposed and don’t protect themselves?”

In the period of capitalist catastrophism, this is how Europe treats its internal peripheries and the Third World despite many EU countries benefiting from selfless acts of international solidarity. Vietnam donated 550,000 masks to Europe, Cuba sent doctors to Italy in an act of medical internationalism and China donated PPE to several badly affected European countries. Europe accepted it all without fanfare and without reciprocation. In short, Europe’s response to the pandemic has been a brutal confirmation of what Aimé Césaire wrote exactly 70 years ago this year: “Europe is indefensible.”

All of this is just a pale imitation of what we can expect as capital’s expansion drags us unwillingly into a warming world. A recent study found that by 2050 up to 1.2 billion people could be displaced, their homes made uninhabitable by searing heat. Yet, in February Germany announced that it would not be considering applications from so-called “climate refugees.” The signs are becoming increasingly clear. Under capitalist catastrophism the imperialist core doubles down on its exploitation of the Third World while shrouding this violence in the ideological garb of doing “whatever it takes” to protect Europe’s citizens.

Here, climate breakdown gets rebranded as a “threat multiplier” to “European interests” as global capitalism transforms itself into a literal death cult, a regime of bio- and eco-apartheid in which the future of many human and non-human lifeforms is really cancelled. They will die in environments that are no longer habitable, drown in our seas, and starve among draughts and floods, the true cause of their suffering denied.

If there is any solace to be found it is that it cannot be long until many — in Europe and beyond — refuse to be thrown onto what Hegel called “the slaughter bench of history.” The state’s increased role in managing capital flows under capitalist catastrophism renders its class character all the more apparent, exposing it to the struggles to come.

-

Capitalist Realism is a Class Project

Lastly, for Fisher, capitalist realism was a neoliberal class project. As he saw it, our inability to imagine the end of capitalism was the effect of “libidinal dampening,” that is, the suppression of our collective desire for something fundamentally better than what capitalism can offer.

On this point Fisher’s understanding of neoliberalism closely resembles that of David Harvey. Both authors interpret neoliberalism as a class project intended to redistribute wealth and power from the bottom to the top so as to entrench capital’s control over society. Yet such “political” or “subjective” interpretations of neoliberalism’s ascendency have a tendency to overlook more economic or “objective” factors such as capital’s crisis in profitability in the 1970’s or neoliberalism’s contingent and piecemeal implementation.

It is because Fisher understands neoliberalism in this way that his thinking around capitalist realism can seem excessively functionalist. The idea often appears in his work as the will of neoliberals made manifest; a total, insidious and near-intractable exercise in political, economic and libidinal engineering orchestrated by a clique of omniscient and omnipotent technocrats.

But if this assessment were ever true, it is no longer today. The coronavirus and climate crisis have revealed that there is no “Big Other,” no conspiratorial cabal of officials instrumentally shaping history. On the contrary, it is all too obvious that capitalists are improvising and improvising badly. From Trump speculating wildly about the healing powers of disinfectants, to Johnson’s advocation of herd immunity and boastful remarks about shaking everyone’s hand before almost dying, our rulers have no idea what they are doing.

These may be extreme examples but they confirm rather than refute the rule. All across Europe the response to the virus has been disorganized and chaotic. From January to March the EU fastidiously ignored warnings about the virus. Then, as deaths began to soar in Italy and Spain, countries implemented unilateral measures: border closures in Poland caused truck tailbacks for 40 kilometers, Viktor Orban’s sweeping emergency measures consolidated his control in Hungary and France and Germany imposed export bans on vital medical equipment. Only after Italy’s death toll reached the tens of thousands did the EU offer a “heartfelt apology” for its lack of coordination, but by then it was too late.

It is because the capitalist class is no longer in control that our situation today has become the inverse of what Naomi Klein calls “disaster capitalism,” the exploitation of a crisis to drive through projects and policies that would never otherwise survive public scrutiny. There is no doubt that we can find examples of what might be called disaster capitalism in response to the pandemic but there is a qualitative difference in how these function as we move towards capitalist catastrophism.

From the perspective I am advancing here the problem with Klein’s theory is that it presumes there is a normal to return to. Disaster capitalists use crises as smokescreens to consolidate their power for the post-crisis times to come. But what happens when there is no post-crisis? What happens when the catastrophic convergence of capitalist exploitation and ecological destruction leads to what David Wallace-Wells calls a “climate cascade,” a scenario in which “natural disasters” cease to be discrete events and start to overlap and compound one and other?

The coronavirus gives us an insight into what this might look like. The capitalist class still uses the crisis to advance their post-crisis interests but they also start to take leave of the rest of us. They retreat to their private jets and holiday homes, they take their personal doctors and their nannies with them into lockdown and they let “low-skilled workers” take the risks of maintaining global supply chains. They start, in other words, to assemble the infrastructure to support the coming climate apartheid. States, meanwhile, work to conceal the severity of the situation, to give an impossible to maintain modicum of stability to those of us living in the First World.

In a perverse way this situation is convenient for Europe’s politicians. Since at least 2008 they have been unable to convince us that things are getting incrementally better for everyone. Wages across the continent have flatlined, unemployment is climbing and debt-to-GDP remains stubbornly high despite more than a decade of austerity. Any one of these events would indicate that the social compromise between Europe’s working class, its technocratic bureaucrats and capital is beginning to disintegrate. Together, they spell a potential disaster for the European Union.

The pandemic has made this disaster more likely but it has also given Europe’s governments a renewed purpose. Under capitalist catastrophism they no longer try to balance the interests of workers and capital to attain what is “best” for Europe. Instead, they pivot towards protecting us from the worse. Borders are strengthened, nationalist sentiments courted, the exploitation of nature and the Third World redoubled. In short, a situation of climate apartheid begins to be assembled.

This is the paradox of capitalist catastrophism: a crisis in government becomes a form of government, the capitalist state’s epidemiological and climatic failures turn back on themselves to become their own solution. In the absence of a genuine left alternative to capitalism, the system now promises to protect those lucky few from events that are of its own making.

The end of capitalist catastrophism?

Gramsci’s aphorism that “the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear” has done a lot of work since the pandemic began. It is usually evoked to suggest that we exist in a volatile nowhere zone between two states, that the uncertainty, anxiety and horror of the present are a passing phase on the path towards something new and, we hope, something better.

But what happens if we cut away the implicit teleology of Gramsci’s aphorism to imagine that the interregnum is the new normal? How would the realization that the “great variety of morbid symptoms” are not going anywhere and are in fact only going to get worse change how we organize? This is the challenge posed by capitalist catastrophism.

Whether consciously or not the left reproduced capitalist realism through the Lilliputian ambition of our struggles, our willingness to work “in and against” a system that had no place for us and our abandonment of struggling along class lines. Under capitalist realism’s influence democracy replaced communism as the horizon of our struggles, equality replaced liberation and fairness replaced revolutionary justice. Now that the haze of capitalist realism is lifting it is time to reverse the situation.

The good news is that capitalism’s increasingly tenuous grasp on what gets to count as realistic means that the social field is more open than it ever was under capitalist realism. Even minor gestures like turning our backs on officials can have a disproportionate effect on public consciousness. But to really break the back of global capitalism Europe’s left will need to think big.

First, we need to return to the problem of transition. If horizontalism failed with the Arab Spring and Occupy Movements and infiltrating bourgeois parties and municipalities failed between 2015 and 2020, then our collective task under capitalist catastrophism is to use our new found powers of imagination to support the difficult and patient work of building organizational and political forms, theories and movements to propel our struggles forward.

Though it is impossible to go into detail on the subject here, I am convinced that this requires the return of the revolutionary party. For all their flaws the movements around Syriza, Podemos, Corbyn and Sanders made a great advance on the so-called movements of the squares by demonstrating that the party-form is uniquely capable of cohering and furthering the interests of the working class. It was the party — albeit of a bourgeois kind — that opened the space for an affirmative, rather than a strictly negative, critique of capitalism to develop — the most notable example of which is perhaps the Green New Deal.

Yet as we now know these movements ran into trouble because they tried to do the impossible: to turn a bourgeois party machine into a party of the working class. Our task today, then, is to strip the party form of its reformist content, to build autonomous, revolutionary, working class parties. Such parties would refuse to participate in bourgeois electoral politics and would instead focus on building the kinds of movements, institutions, cultures and practices that can make a real difference to our lives within capitalism while pointing the way beyond it.

By unifying the left, by serving to bolster and consolidate the gains of the kinds of spontaneous uprisings that we have seen across the world in response to George Floyd’s murder, this kind of party can serve as an agent of revolutionary transition.

Second, we must forge what Samir Amin calls “the possible, but difficult, conjunction of the struggles of the people in the south with those in the north.” Today’s crises are planetary in scale and demand a planetary response. As Mike Davis writes in his analysis of COVID-19, we need to imagine and fight for something like a “truly international public health infrastructure.”

But we also need an internationalist response to the climate crisis. The more progressive versions of the Green New Deal are a good start but most assume the use of unsustainable technologies and subordinate the needs of the Third World to those in the First. To counteract this we must find ways to coordinate our struggles across state lines and to expose how — as Fanon argued — our very way of life in Europe is predicated on the subordination of the Third World. Only then can we break our chains of uneven and combined dependence, stave off capitalist catastrophism and build a world held in common.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/capitalist-catastrophism/

Next Magazine article

A Europe Too Far: The Myth of European Unification

- Igor Štiks

- June 17, 2020

Far-Right Political Terror in Europe

- Liz Fekete

- June 17, 2020