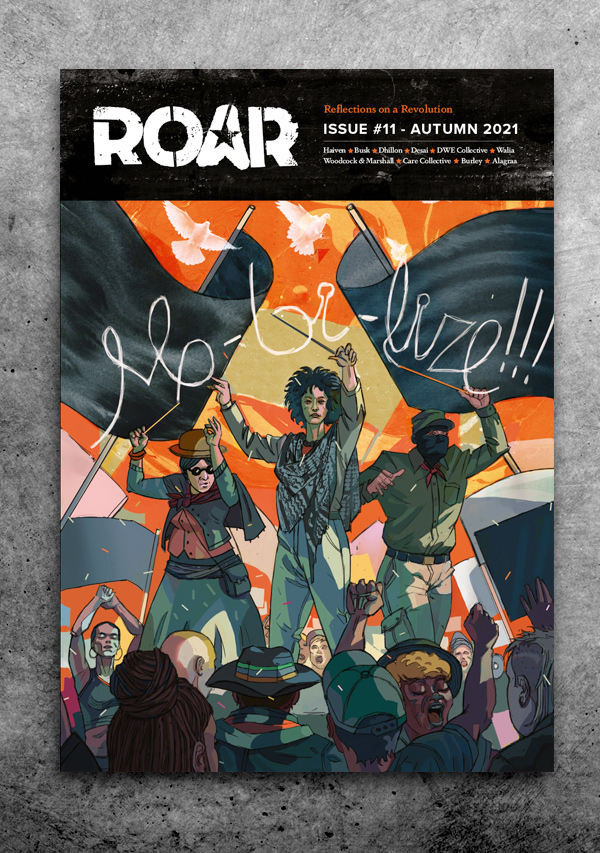

indigenous struggles

Solidarity between Indigenous liberation movements fosters their resistance against capitalism and settler colonialism in its many different forms.

Internationalist Solidarity from Turtle Island to Palestine

- Issue #11

- Author

This past year, in the weeks leading up to the May 15 anniversary of the Nakba — the 1948 ethnic cleansing and mass exodus of the Palestinian people from their homes and lands — the people of East Jerusalem experienced the worst unrest in years. Racist Israeli settlers backed by Israeli police and army attacked Palestinians in their neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan. The violence was a continuation of the settler colonial Israeli state’s policies and practices of ethnic cleansing and illegal land annexation.

The violence intensified during the holy month of Ramadan, as Israeli occupation forces — police in riot gear — raided the Al-Aqsa Mosque, gassed worshipers, attacked and arrested many Palestinians. Hamas, the political party and militant resistance group that governs Gaza, warned that if Israel did not halt its crackdown on Palestinian worshipers at the mosque it would retaliate. In response, rather than cease police brutality and stop settler lynch mobs from attacking Palestinians and shouting genocidal chants in the streets such as “Death to Arabs!” and “May your village burn!”, the Israeli military instead launched airstrikes on the besieged Gaza Strip — killing hundreds and injuring thousands of people.

Palestinians who took to social media to share videos of police brutality in East Jerusalem and the bombing of Gaza under the viral hashtags #SaveSheikhJarrah and #GazaUnderAttack saw their content censored. Meanwhile, Western media predominantly framed the violence in Jerusalem as “clashes” or “tensions” and framed the attack on Gaza as a “conflict” between two equal parties, suppressing the history of forced dispossession and settler colonial violence by the Israeli state. Palestinians rose up en masse in what has since become known as the Unity Intifada, uniting the geographically and politically fragmented Palestinian people across historic Palestine and the diaspora. In addition, demonstrations began to take place across the world opposing the Israeli attack on Gaza and the general brutality against Palestinians in East Jerusalem and elsewhere.

As thousands took to the streets organizers from the Movement for Black Lives, migrant, racial and climate justice struggles, LGBTQ and feminist movements joined in solidarity demonstrations. Idle No More, an Indigenous movement in Turtle Island — a common Indigenous name that refers to North America — released a statement of solidarity with the Palestinian people and “against ongoing Israeli attacks and enforced settler colonialism.” In their statement, Idle No More recognized the actions of the Israeli state as an act of genocide and called upon the US and Canadian governments as well as the United Nations to boycott, divest from and sanction the Israeli government for “international crimes against humanity.” In the case of genocide, silence is complicity, they point out. The statement ends by stating that “Israel has one of the largest armies in the world today and it is heavily funded by the United States government. To call these actions a ‘war’ with two equally opposing sides is an erasure of settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing.”

Like Palestinians, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island, have been resisting settler colonial violence and the endless ways it has impacted upon their lives. Since its founding in 2012, Idle No More has been resisting the Canadian state’s violation of Indigenous treaties and the theft and destruction of unceded territories and water by the government and industry. Idle No More’s statement is the latest expression in a long tradition of political solidarity that dates back decades, demonstrating their affinity with the Palestinians in their struggle against settler colonialism.

Like Palestinians, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island, have been resisting settler colonial violence and the endless ways it has impacted upon their lives.

In a similar fashion to the long tradition of solidarity between Black and Palestinian liberation struggles, the solidarity that exists between Palestinian and Indigenous struggles is about relationality and extending kinship. One year earlier, in February 2020, the Wet’suwet’en (a First Nations people composed of five clans that live in the interior of British Columbia) rose up to refuse and resist a Supreme Court of Canada injunction that ordered them to evacuate their ancestral lands to make way for the Coastal GasLink Pipeline. Palestinian leftists and Palestine solidarity activists in Canada put their bodies on the front lines during the railway, highway and port blockades and infrastructure shutdown led by Indigenous nations. During these uprisings, the Boycott National Committee in Palestine issued a statement expressing their solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island.

“As Palestinians, we have first-hand experience with a colonial power, Israel’s regime of occupation, colonization and apartheid, that systemically works to dispossess, divide and strip us of our lands and resources. We know too well, from our own experience, that the TransCanada Coastal Gaslink pipeline aims to steal Wet’suwet’en land, use resource extraction to solidify control over Indigenous territories, destroy the environment and violate Indigenous laws. We also know that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) attacks, sanctioned by the Trudeau government, against the Hereditary Wet’suwet’en leadership, matriarchs and land defenders, are used to violate Indigenous sovereignty. The RCMP is employing tactics and equipment similar to Israel’s government, including Caterpillar bulldozers, to seize indigenous lands.”

The statement underscored the ways that settler colonial and imperialist forces undermine Indigenous political orders across geographies using similar structures, tactics and technologies of violence for land theft, territorial expansion, resource extraction, repression and the criminalization of resistance.

On January 28, 2020, at the same time Canada was being shut down in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en struggle, the Trump administration in the US announced the self-proclaimed “Deal of the Century,” a so-called “peace plan” for Israel-Palestine and the broader Middle East. The plan was devised by Israel in collaboration with the Trump administration and in consultation with officials from Gulf States, but without Palestinian input or consent. This plan sought to legitimize the annexation of Palestinian land, water and other natural resources.

While the world was battling against the COVID-19 pandemic — the effects of which were especially severe on the disenfranchised — the Israeli government alongside the Trump administration attempted to formalize its annexation of Palestine. Around the globe, people took to the streets in protest to express their outrage about Trump’s plan and in Canada, Indigenous activists mobilized in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle.

The solidarity between Indigenous struggles against colonial capitalist violence from Palestine to Turtle Island is part of a long tradition of organized resistance that has been built over many decades, as they have been resisting settler colonial capitalist regimes that have attempted to eliminate these societies from their homes, lands and life. The intensification of colonial violence across these geographies, the continuous theft of land, water and natural resources and the environmental destruction caused by the colonial regimes of Canada and Israel have led movements to build what Nishnaabeg writer Leanne Simpson calls “constellations of co-resistance.”

As imperialist capitalist violence across settler geographies is intensifying, constellations of co-resistance offer a way out of settler-colonialist thought and representation by building collective power between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities who are fighting different aspects of the same colonial and capitalist system. Decades of solidarity between the Indigenous movements of Turtle Island and the Palestinian liberation movement have affirmed that constellations of connection like direct action and popular mobilization to disrupt settler economies and governance are effective in pushing the agenda of Indigenous liberation.

At the same time, the history of Indigenous internationalist solidarity has taught us that social movements should not only look to one another based on their historical similarities, but also examine the specificities of the colonial condition within their local geographies. This helps to foster an understanding of the similarities as well as the differences between struggles, and points to the strategic benefits of conjoining struggles as comrades and peoples fighting for mutual liberation.

Settler colonial regimes

Canada and Israel are both settler colonial states shaped by racial capitalism and built on Indigenous dispossession and slave, migrant and indentured labor. Settler colonialism in each geography has been structured in analogous ways on the basis of legal apparatuses, land theft, dispossession, restriction of movement, racial segregation, denial of national status, gendered and sexual violence, resource extraction, racialized labor exploitation, policing and incarceration. The fundamental goal of a settler colonial regime is to eliminate the Indigenous people from the land — either through elimination or assimilation – and replace them with a white settler society and their systems of governance. Land theft and dispossession have played a central role in the history of capitalist accumulation, the enclosure of the commons and the privatization of land that underpins the formation of Canada and Israel as settler colonies.

Though the Canadian and Israeli states share similar tactics and strategies in their pursuit of Indigenous dispossession and racialized labor exploitation, the two states also have distinct histories of state formation and different political and legal apparatus that shape settler governance in both of these contexts. While Indigenous peoples across both geographies have been resisting settler colonialism, using various methods specific to their local contexts, it is imperative that organizers and scholars avoid conflating the two settler colonial regimes as each geography has a place-specific history and state structure.

Viewing the relations between the Canadian and Israeli states and their respective Indigenous populations through the analytical framework of capitalism and settler colonialism has allowed for a structural analysis between Indigenous resistance movements to expose how their struggles are connected. Consider, for example, the police and military technologies that are used to repress Indigenous land and water protectors across Turtle Island and Black Lives Matter activists in Ferguson and Baltimore and to surveil migrants crossing the Canada and US borders. These technologies were first used on Palestinians, then proudly marketed as “battle tested” before being exported to police departments, border agencies, homeland security, and military abroad.

Strengthening ties and mobilizing in collective action

The most recent resurgence of solidarity between Indigenous peoples and Palestinians in Canada was predated and prefigured by a first wave of internationalist solidarity at the height of the Cold War in the 1970s. This was during the era of Red Power, anti-imperialist movements and Third World decolonization, in which the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) figured prominently.

In 1970s Vancouver, an organization calling itself the Third World People’s Coalition — comprised of several organizations, including the Canada Palestine Association, the Native Study Group (NSG), the African Progressive Study Group and the Indian People’s Association in North America, among others — organized many actions and educational events. This included hosting a PLO delegation that spoke with Red Power activists in Vancouver in 1976, mobilizing support for Palestinian revolution. It also included building bonds between struggles, like at the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs conference, where Palestinian revolutionary films were screened, attendees read and circulated the autobiography of the Palestinian militant Leila Khaled and letters condemning the Canadian media’s denunciation of the PLO were distributed.

This raised the consciousness of those who were active in the political struggle for Indigenous rights. As each movement educated itself about the other’s struggles, it enabled organizers to strengthen ties and mobilize in collective actions, such as the weekly solidarity demonstrations in 1976 when Leonard Peltier — a leader in the American Indian Movement (AIM) — was detained in Vancouver before his extradition to the US. Leonard Peltier was accused — and later convicted — of the killing of two FBI agents during a confrontation between the Bureau and AIM on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1975. Peltier, who has always denied the charges, was imprisoned in 1977 and is still incarcerated today after 40 years in prison, despite years of campaigning for his clemency on the part of Indigenous movements, Amnesty International and high-profile figures such as Nelson Mandela.

The most recent resurgence of solidarity between Indigenous peoples and Palestinians in Canada was predated and prefigured by a wave of internationalist solidarity in the 1970s.

In 1990, during the Siege of Kanehsatà:ke and Kahnawá:ke — commonly known as the Oka Crisis, a 78-day armed standoff in the settler town of Oka, Quebec between the Mohawks of Kanehsatà:ke on the one hand, and the Quebec police and Canadian Army on the other — Palestinian activists affiliated with the PLO participated in direct actions during this seminal struggle. The tactical lesson Indigenous warriors had learned from Palestinians that were waging their First Intifada in the streets of the West Bank and Gaza in the late 1980s were put into practice. In particular, as their land defenders were being criminalized, the First Intifada became an inspiration and model of civil disobedience that would allow them to engage in militant resistance while avoiding retaliation by the state.

A decade later, in the mid-2000s, a new generation of Palestinian and Palestine solidarity activists further developed their relationships with Indigenous liberation struggles by making connections between apartheid systems. Activists connected settler-colonial displacement of Indigenous people across geographies, linking infrastructures of settler colonialism such as the South African pass system, Israeli checkpoints and apartheid walls, as well as carceral systems and police and military infrastructure designed by settler-colonial states that were learning from one another.

In the mid-2000s the analytical connections made between the Native reservations in the US and Canada and the Bantustan system in South Africa led organizers to identify apartheid as a core feature of settler colonialism. Organizers looked at the historical antecedents of the reservation systems in North America to understand how these logics are prevalent today in occupied Palestine. Understanding Canadian settler colonialism as an apartheid system allowed for activists to connect their struggles across colonized territories.

At the 2001 World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa, delegates declared Zionism as a form of racism and the Palestinian reality of living under Israeli apartheid became far better understood. The Canadian state was against the delegates’ stance on Israel-Palestine, thus Canadian political leaders labeled the conference as an “anti-Semitic hatefest.” This further strengthened Palestinian organizations and the Palestine solidarity movement in Canada to recognize the interconnections between Israeli apartheid and settler colonialism in Canada and the need to support Indigenous sovereignty struggles across Turtle Island. It also created the opportunity for pro-Palestinian groups to clarify the nature of Zionism as an exclusivist colonial and racial project, similar to other settler regimes.

Crucial disruptions

These analytical and political connections between different communities suggest that Palestinian and Indigenous liberation movements are inextricably bound in what feminist author and professor Nadine Naber describes as “conjoined struggle.” Reflecting upon internationalist formations of solidarity that Black and Palestinian activists have built across struggles and generations, Naber suggests that oppressed communities “should look to one another not because their struggles share similarities, but because their struggles are conjoined — and have been so for some time.” What joins these communities together is that they share a common enemy in global power structures of violence and brutality. The US-Israeli alliance; US-led empire building, militarism and war, neoliberal economics and white supremacy are among the conjoined forces of global power that structure Indigenous, Black and Palestinian oppression. Key to resisting these conjoined forces is building collective power and solidarity across difference, which in turn tends to the formation of the above-mentioned constellations of co-resistance. Conjoining struggles cultivates co-resistance.

Palestinian organizations and Palestine solidarity activists further conjoined with Indigenous struggles by actively participating in various Indigenous land reclamation actions in the mid-2000s, including at Secwepemc Nation at the Suns Peak Resort, at Grassy Narrows, Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug (KI), Barrier Lake and Ardoch, and on Haudenosaunee land in Tyendinaga, Kanenhstaton, Kanehsatà:ke, Kahnawá:ke and at Six Nations. Organizers in the Palestinian liberation movement also showed their solidarity by actively supporting the release of native political prisoners Shawn Brant, the KI Six and others.

Analytically, organizers within these movements deepened their anti-colonial politics by centering the question of decolonization in all its forms, paying particularly close attention to the issue of land and dispossession. In 2005, after the Palestinian call for “Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions,” the joint struggle towards decolonization also inspired dialogue and discussions between organizers across Turtle Island exploring ways to grow the international solidarity movement with Palestine.

Palestinians adopted the tactic of boycott during the initial period of colonization in the early 1900s. The contemporary use of the tactic of boycott was internationalized as various localized groups around the world began to develop BDS campaigns in solidarity with Palestine, inspired by the South African anti-apartheid movement. Global movements including Indigenous struggles also expressed their solidarity with BDS, in particular the Idle No More movement, the Red Nation and coalitions that have explicitly called for the boycott, divestment and sanctions of the Israeli state.

What joins these communities together is that they share a common enemy in global power structures of violence and brutality.

Indigenous nations and Palestinians have also challenged their oppressors through fierce disruption of economic activities, such as the economic boycotts during the 1987 Palestinian Intifada, the blocking of critical infrastructure such as rail lines and highways to disrupt supply chains in Canada and the development of self-reliance strategies to minimize economic dependence on the colonial state. Widespread economic disruption intensified through direct action and Indigenous militancy. Mass insurgencies in the 1970s and 1980s produced political-economic crises that forced both Canada and Israel to enter into negotiations with Indigenous nations and Palestinians respectively in an effort to maintain the settler state’s sovereignty and dominant capitalist economies.

Such disruptions are crucial because when movements can disrupt the flow of capital within settler economies, colonial states are forced to consider Indigenous concerns and demands. Still, when the state attends to Indigenous demands it often tends to fold them within the structures of the regime. The shift of the Canadian state’s approach to Indigenous resistance under the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is one example of this.

The Trudeau government fully embraced what Dene scholar Glen Coulthard calls “the politics of recognition” and its accompanying spectacle of reconciliation. Recognition shifted the focus away from Indigenous land claims and sovereignty to shared history and cultural recognition — essentially disavowing the material demands of Indigenous nations and embracing their cultural identities and practices as part of assimilating them into the “multicultural” state. This is why the ongoing Wet’suwet’en resistance against extractive industry projects such as the Coastal GasLink pipeline and the ensuing economic shutdown of Canada have been so significant: they exposed the veneer of reconciliation for what it is and pronounced it dead.

In the case of Israel, Trump’s “peace plan” explicitly revealed itself as an Israeli economic endeavor that simply perpetuates land theft, dispossession, settlement construction, consolidates apartheid and liquidates Palestinian aspirations to a state, self-determination and the right of return. Mass Palestinian rejection of the plan again exposed “peace” for the facade it has been for a long time, from the Oslo Accords to the Trump plan. Popular resistance committees across occupied Palestine continue to organize weekly protests against the ongoing annexation of Palestinian land, water and other resources.

Poetic Solidarity

Another space through which Indigenous peoples and Palestinians have expressed their kinship, solidarity and relationality to one another is through art. In 1992, the renowned Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote “The Red Indian’s Penultimate Speech to the White Man” in which he describes the elimination of Indigenous life by European settlers. Amid theft and erasure, the poem identifies the kinship that he as a Palestinian has with understanding conquest and the “war of elimination” of both the living and the dead. He recites,

Columbus, the free, looks for a language

he couldn’t find here,

and looks for gold in the skulls of our good-hearted ancestors.

He took his fill from our living

and our dead.

So why is he bent on carrying out his war of elimination

from the grave, until the end?

In 2012, as Gaza was being bombed, the late Sto:lo author and Indigenous feminist Lee Maracle wrote a poem titled “Remember Mahmoud 1986.” Maracle met Darwish in the 1970s in Vancouver during the PLO’s visit and recited Darwish’s poetry at a gathering. Inspired by his poetry and their interactions, she memorializes him in the poem by addressing the ongoing Palestinian Nakba that continues to eliminate Palestinian life. Maracle compared the shelling of the open-air prison to the massacre of Wounded Knee tying genocide of Indigenous peoples across territories. She ends her poem with her expression of solidarity with Palestine by underscoring her commitment to the struggle as an internationalist, centering Indigenous kinships and co-resistance across time and space,

My commitment to Palestine

Floats on the light emanating from his eyes and captures my heart

I whisper Palestine, Palestine – Free Palestine

Wounded Knee, Wounded Knee, no more Wounded Knees

I imagine him listening, hearing me

Nearly smiling

Just before he throws his stones

The poetry of Darwish and Maracle not only discusses the colonial past and present, but also expresses their shared revolutionary consciousness and internationalist political orientation, which has been profoundly influential for generations that have followed after them. Their poetic solidarity has inspired a new generation to produce poetry that connects their struggles. For example, the Palestinian spoken word poet Rafeef Ziadah has written several poems connecting the Indigenous/Palestinian struggle and experience. A poignant line from her poem “Trail of Tears” captures the ongoing forced dispossession and its devastating impacts from Palestine to Six Nations. She recites: “We are still walking a Trail of Tears from Tyendinaga to Six Nations”.

Cree writer Erica Violet Lee wrote her poem “Our Revolution” during the 2014 Israeli massacre on Gaza. In it she memorializes the stories of colonial violence enacted upon Indigenous/Palestinian women and girls. She writes,

You and me, we know violence:

The pain of our mothers,

The memories of this land

We share a history of being moved,

Removed,

Moved again

Taken from our homes

And wondering if we’ll ever go back

You and me

We’re the nation

And this is for the mother and daughter leading movements from Gaza to the grasslands

Erica Violet Lee connects the gendered violence of colonialism and the ways in which it shapes the realities of Indigenous women across settler geographies through poetry, placing them into conversation by threading their memories of resistance in their shared revolution. Art is an important site of struggle as colonial forces continue to suppress, censor and erase Indigenous narratives, thought and culture. It is also an invaluable space for expressing poetic solidarity, speaking with each other across time and space and developing anti-colonial kinships as part of the struggle.

Lessons from conjoined struggle

Indigenous struggles from Turtle Island to Palestine have many lessons to teach social movements today. The first is the necessity of direct action and economic disruption: when resistance is organized to disrupt flows of capital, settler states and their allies are forced to take Indigenous demands seriously. Another important lesson is to trace the circulation of goods that are produced in settler states to connect global power structures and their regimes of violence transnationally. Consider, for example, the Israeli weaponry that is routinely tested on Palestinians — particularly during attacks on Gaza — and are sold on the global market to various countries and used against marginalized populations within those states.

Another lesson to glean from these struggles is the importance of developing meaningful principled solidarity by building constellations of connections by either supporting one another’s actions, establishing joint campaigns and developing relationships, as well as cultural production that can sustain our spirits.

A poignant example that encapsulates some of these lessons was witnessed during the recent attacks on Gaza and Jerusalem, as Palestinians organized a general strike across all of historic Palestine on May 19 2021 and reiterated their appeal for meaningful international solidarity especially in the form of BDS. When the Palestinian General Federation of Trade Unions called for solidarity, we witnessed the remarkable solidarity of trade unions — specifically dock workers from Italy, South Africa, the US and Canada who heeded the call and refused to handle cargo from ZIM Integrated Shipping Services Ltd., the largest and oldest Israeli cargo shipping company. Following the successful blockage of a ZIM container ship in Oakland in early June, it then sailed to Prince Rupert Port, Canada, where it was prevented from docking at the port on June 14 after a group of organizers blocked the entrance to the container terminal. The ship was turned away before being allowed to unload its cargo a few days later. First Nations activists and local unionized dock workers united in Prince Rupert Port as part of the #BlockTheBoat campaign.

Years of struggle have taught us that solidarity has to be based on shared principles of liberation.

Such acts are significant as they rupture the flow of both Israeli and global capital. Lara Kiswani, a leader with Block the Boat and executive director of the Arab Resource and Organizing Center in an interview with AJ+ said: “It’s incredible what we’re seeing. The First Nation siblings in Prince Rupert were able to demonstrate what international solidarity is, and what’s at stake for us to stand in solidarity with Palestine, because they understand settler colonialism.”

The disruption of capital — in this instance of the ZIM ship — was only possible because of international solidarity that was practiced across various locals and movements and organized in a collective campaign to #BlockTheBoat. This type of struggle is at times challenging, as such intentional work is consistently needed to build solidarity between struggles ethically, responsibly and carefully.

There are many pitfalls that we must be mindful of in the process of trying to build such solidarity. Over the past few decades, those within these struggles have cautioned against tokenism, organizing models that are based on crisis responses rather than sustained movement building. Another is colonial exceptionalism, in which activists engage in a form of “oppression Olympics” — essentially competing to establish who is more oppressed. This work requires organizers and movements to consider challenging hetero-patriarchal, gendered, sexual and racial violence towards each other.

Years of struggle have taught us that solidarity has to be based on shared principles of liberation. This demands a commitment to mutual self-determination and collective visions for the transformation of society — essentially adopting a politics of co-resistance. Most importantly, while building internationalist solidarity is crucial during these times, it is imperative that movements do not collapse distinct specificities of the colonial condition within their local geographies through frameworks of historical similarities.

Also important is to ensure that local elites and their political economic agendas are challenged. For example, some members within Band Councils in the context of Canada or the Palestinian Authority which governs the occupied West Bank have been complicit in collaborating with the settler states that oppress their peoples. Thus, it is imperative to not only resist the settler state but also to oppose Indigenous collaborators that reproduce and capitulate to capitalist state violence.

This also reveals the limits of identity politics. On the one hand, identity is important to consider as violence is organized and enacted through the use of class, racial, gendered and sexual logics. On the other hand, it is necessary to be critical of the native bourgeoisie class that advance the colonial states’ agendas.

Read the full issue here.

When movements are uncritical of the internal contradictions within their membership, communities, or of their representatives and leaders, or espouse uncritical politics within their ranks, it can hinder solidarity formations. Otherwise, organizers and movements can become complicit in advancing colonial and neoliberal “politics of recognition” and “peace” and/or other forms of capitalist violence.

While conjoined struggle can be messy and is often embedded with tensions, contradictions and limitations, it is crucial that political movements in this time continue to strengthen their structural analysis of the capitalist colonial logics of elimination. A central tenet of international solidarity is that it has to be based on shared principles of liberation, demanding a commitment to mutual self-determination and collective visions for the transformation of society.

Gleaning insights from these lessons is one of the necessary conditions for deepening constellations of co-resistance that organizers and movements have taught us from Turtle Island to Palestine. Only by establishing material bonds of solidarity and by enacting and embodying a politics of internationalism we can truly decolonize and abolish systems of oppression and exploitation. Through the unification and globalization of these struggles, alternative pathways can be imagined and enacted to escape settler colonialism and its logics. As Lee Maracle reminds us in her poem “Blind Justice”:

We will need to nourish our imagination

To include a new equality

And summon our souls, our hearts and our minds to a justice,

which includes all life

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/internationalist-solidarity-turtle-island-palestine/

Next Magazine article

Building Communities for a Fascist-Free Future

- Shane Burley

- December 15, 2021

Freedom to Stay, Freedom to Move: An Interview with Harsha Walia

- Harsha Walia

- December 15, 2021