Book Review

The Invisible Committee propose to actualize the political potential of the squares by reconsidering revolution—not as an objective, but as a process.

Reopening the Revolutionary Question

- Issue #0

- Author

Seven years after publishing that paradoxical subversive bestseller that was The Coming Insurrection, the Invisible Committee’s most recent book, entitled To Our Friends, starts by confirming that “the insurrections, finally, have arrived”: from the Arab Spring, 15-M and Syntagma Square to Occupy and Gezi Park.

From there it makes a wager: in the movements of the squares we could find early indications of a “civilizational mutation”—but one that still lacks its own language or compass, burdened by the weight of ideological legacies from the past and in the midst of great confusion.

1. Expand the squares

To Our Friends is a small event in the publishing world, not in the sense of being a sales or marketing success, but rather in the sense of being an anomaly in its form of writing and publishing. This is not a book by an author, another personal brand in a network of names, but comes signed by the fictitious denomination of a constellation of collectives and people who sustain that “the truth does not have an owner.”

This is not a book that arises simply from reading many other books, but also from a set of experiences, practices and struggles, that they consider important to think and tell to themselves. It is not a book that seeks to fuel a “sound of the season” or to convince anyone of anything, and therefore it is directed “to friends,” to those who in some in some way are already walking together even without knowing each other, proposing a series of signals, such as those indentations left by hikers for other lovers of long walks, with the difference that this path did not previously exist, but rather is made—collectively—by walking.

The starting point for the book are the potentialities and limitations of the movements of the squares—not understood as a scattered series of unconnected eruptions, but rather as a historical sequence of intertwined uprisings. These movements erupt and profoundly alter the contexts in which they operate, drowning legitimacies that seemed as solid as rock and redescribing reality. In the end, however, they seem to crash against the wall of macro-politics before entering into a gradual reflux, as happened in the cases of Occupy and Gezi.

It is here that the “hegemonic operation” appears, or can appear. Taking advantage of the rupture and the shift in common sense generated by the climate of the squares, it is about conquering public opinion, votes, and institutional power, to force the limits of parliamentary democracy from within through a truly social democratic politics, as has happened with SYRIZA in Greece and Podemos in Spain.

Can we imagine a non-electoral or non-institutional expansion of the squares’ potential? The Invisible Committee propose their own alternative: to reopen the revolutionary question.

Are there other options? Can we imagine a non-electoral or non-institutional expansion of the squares’ potential? Of course this question does not presuppose a simple return to micro-projects, local struggles and the small in-group of the already-convinced. Between the revival of political verticalism and the temptation of nostalgia, how do we keep going—and go even further? If it is not hegemony we are aiming for, then what kind of politics can we imagine?

The Invisible Committee propose their own alternative: to reopen the revolutionary question. That is, to reframe the problem of the radical transformation of the existing; a project shut down by the disasters of twentieth-century authoritarian communism. To pursue a rupture with parliamentary democracy as the only possible framework and the emergence of a new form of life. To make the revolution, “not as an objective, but as a process.”

2. Ethical truths

The burning body of Mohamed Boauzizi in front of the Sidi Bouazid police station in Tunisia. The tears of Wael Ghönim during the televised interview after being liberated from secret detention by the Egyptian police. The nighttime eviction of 40 protesters in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol.

The scenes that in recent years have had the power to open up political situations do not oppose knowledge to ignorance. In these scenes, there are words and voices rather than speeches and explanations. There are common and anonymous people who say “enough!” There are bodies that courageously occupy space doing what they should not be doing. There are gestures that are crazy in the sense of being unpredictable and impossible, defying the state of things with bare life. There is the heavy police materialization of an odious order.

These are scenes that, for everyone, redefine and displace the threshold between what we tolerate and what we will no longer tolerate. Scenes that move us and that call for a break, a clash—between dignified lives and the lives unworthy of being lived.

The Invisible Committee asserts that if the movements of the squares have unseated the “lifelong activists,” it is because of this: they don’t start from political ideologies, from an explanation of the world, but from ethical truths.

How is an “ethical truth” different from a “truth” as we are used to thinking of it, as a statement and a thing? Well, the truth as a simple objective statement does not in itself possess the ability to shake up reality. A delegitimized power can continue to operate because it is not fundamentally sustained by our agreement and consensus, our belief or faith in their explanations, but rather by the subjection of bodies, the anesthesia of sensibilities, the management of the imagination, the logistics of our lives, the neutralization of action.

Ethical truths, by contrast, are not mere descriptions of the world, but assertions based on the ways in which we inhabit the world and conduct ourselves in it. They are not external and objective truths, but truths of sensibilities: what we feel about something, more than our opinion. They are not truths that we hold alone, but truths that connect us to others who perceive the same thing. They are not declarations that can leave us indifferent, but they compromise us, affect us, require us. They are not truths that illuminate, but truths that burn.

Politics consists of constructing—based on what we feel as a truth—desirable forms of life, capable of lasting and materially sustaining themselves.

If the Invisible Committee confirms that the political potency of the squares resides in their ethical truths it is because they take us away from individualism and connect us everywhere to people and places, to ways of doing and thinking. Suddenly we are no longer alone confronted with a hostile world, but interlinked. Affected in common by the immolation of someone similar, the demolition of a park, the eviction of a neighbor, disgust for the life that is led, the desire for something else.

We feel that one’s destiny has to do with the destiny of others. The emotion of the words shared in the squares had to do with the fact that they were words magnetized by those truths that convey other conceptions of life.

Politics, then, consists of constructing—based on what we feel as a truth—desirable forms of life, capable of lasting and materially sustaining themselves: ethical truths giving themselves a world.

3. Critique of democracy

For the Invisible Committee, the demand for democracy—under any of its forms: representative, direct, digital, constituent—does not have to do with the ethical truths that emanate from the squares. On the contrary: the imaginary and the horizon of democracy fatally divert us, leading us onto a mine field. It clashes with the common sense of the movements of the squares, summarized in the famous slogan “real democracy now.”

In the democratic agora, rational beings argue and counter-argue to make a decision, but the assembly that brings them together continues to be a space separated from life and the world: it is separated, in fact, to better govern them. One governs by producing a void, an empty space (so-called “public space”), where citizens deliberate free from the pressure of “necessity.” The materiality of life—that which, disconnecting it from the political, we designate as “reproductive,” the “domestic,” the “economic,” “survival” or “everyday life”—remains outside, at the door of the assembly.

The Invisible Committee’s critique of direct democracy is not only a theoretical or abstract critique, but can be better understood as an observation of the impasses and blockages of the recent movements’ assemblies: words that are distanced from action, putting themselves “before”; decisions that don’t implicate those who make them, stifling free initiative and dissent; the fetishism of procedures and formalisms; power struggles to condition decisions; centralization and bureaucratization; and so on. For the Invisible Committee, none of this is “accidental,” but rather “structural.” It has to do with the separation instituted by the assembly between words and acts, between words and worlds of sensibilities.

For the Invisible Committee, the potential of the squares did not reside in the general assemblies, but in the encampments; that is, in the self-organization of life in common.

For the Invisible Committee, the potential of the squares did not reside in the general assemblies, but in the encampments—that is, in the self-organization of life in common, through the creation of infrastructures, solidarity kitchens, childcare centers, medical clinics, libraries, and so on. The encampments were organized according to what the Invisible Committee calls the “paradigm of inhabiting,” which opposes that of “government.”

In the paradigm of inhabiting, there is no void or opposition between the subject and the world. Rather, worlds give themselves form. There is not a decree of what should be done, but an elaboration of what already is. It does not function based on a series of methodologies, procedures and formalisms, but as a “discipline of attention” to what happens.

Decisions are not made, neither by majority nor by consensus, but rather they ignite; they are not choices between given options, but inventions that emerge from the pressure of a concrete situation or problem. And those who “invent” decisions apply them themselves—confronting them with reality, making every decision an experience.

Ultimately, democracy does not only form part of the paradigm of government, but it also does so in an insidious way, as it aims to confuse the governing and the governed. A cry like “they don’t represent us” opens a scandalous breach, but it never takes long for a “true democrat” to arrive to assure us that, this time around, with him, there will be “a government of the people.” And so the governed are reabsorbed into the governing again.

A power that is relegitimized this way, a power that is said to emanate from “the people in action”—for example, a “government of the 99 percent” emerging from the squares—can be the most oppressive of all. Who could question it? Only the 1 percent. The part is made to pass for the whole and it places the adversary in the position of a monster, a criminal, the enemy to demolish.

It is in this sense that the memory of 15-M will always be a dangerous field of dispute, as a “destituent tide” and the creation of “ungovernable” self-organized worlds, without a trace of “constituent power” or a “new institutionality” emerging from it. One becomes and remains ungovernable, then, by refusing to legitimate oneself by reference to a superior principle; by happily staying forever naked like the emperor from the story, assuming the always local and situated, arbitrary and contingent character of any political position.

4. Power is logistical

Surround, assault, occupy the parliaments: the sites of institutional power have bewitched the attention and desire of the movements of the squares—and, maybe because of this, the electoral route is their logical continuation. But is it certain that that is where power lies?

The Invisible Committee has a very different idea: power is logistical and resides in infrastructure. It is not of a representative and personal nature, but architectural and impersonal. It is not a theater, but a steel structure, a brick building, a channel, an algorithm, a computer program.

For the Invisible Committee, power is logistical and resides in infrastructure. It is not of a representative and personal nature, but architectural and impersonal.

The Invisible Committee believes that government does not reside in the government, but that is incorporated into the objects and infrastructures that organize our everyday lives—the objects and infrastructures on which we completely depend. Any constitution is worthless; the real constitution is technical, physical and material. It is written by those who design, construct, control and manage the technical infrastructure of life, the material conditions of existence. A silent power, without speech, without explanations, without representatives, without talk shows on TV—a power to which it is totally useless to oppose a discursive counter-hegemony.

For the Invisible Committee, it is not about “taking over” the technical organization of society, as if this were neutral or good in and of itself, and it were enough to simply put it in the service of other objectives. That was the catastrophic error of the Russian Revolution: distinguishing the means from the ends—thinking, for example, that labor could be liberated through the same chains of capitalist assembly. No, the ends are not inscribed in the means: each tool and each technique configures and at the same time embodies a certain conception of life, a world of sensibilities. It is not about “taking control” of the existing techniques, but subverting, transforming, reappropriating, hacking them.

The hacker is a key figure in the Invisible Committee’s political proposal. Or, better, the hacker spirit—in the broad, social sense, beyond the purely digital—that consists of asking, always while doing: “how does this work?”, “how can its operation be interfered with?”, “how could this work differently?”

The hacker spirit is concerned with sharing knowledges. The hacker spirit breaks the naturalization of the “black boxes” amongst which we normally live (opaque infrastructures that constrain our everyday gestures and possibilities), making the operating codes visible, finding faults, inventing uses, and so on. But this is not about substituting “a thousand hackers” for Trotsky’s “thousand technicians.”

To collectively become hackers involves thousands of people blockading an infrastructural mega-project that threatens to devastate a territory and its forms of life. A becoming-hacker of the masses is thousands of people constructing small cities in the squares of large ones, capable of reproducing all parts of life for weeks on end.

5. The communes

Classical politics propagated the desert because it is separated from life: it takes place in another site, with other codes, in other times. It generates the void—the abstraction of sensible worlds in order to govern—and therefore it expands it.

The revolution would be, by contrast, a process of repopulating the world: life surfacing, unfolding, and self-organizing, in its irreducible plurality, on its own.

As a political proposal, the Invisible Committee names the “commune” as the form that could be given to that self-organized unfolding of life. The French word “commune” has at least two meanings (along with its quite important historical evocation): a type of social relation and a territory.

As a political proposal, the Invisible Committee names the “commune” as the form that could be given to that self-organized unfolding of life.

The commune is, on the one hand, a type of relation: faced with the idea of existential liberalism that each person has their own life, the commune is the pact, the oath, the commitment to face the world together. On the other hand, it is a territory: places where a certain sharing is physically inscribed, the materialization of a desire for common life.

Does the Invisible Committee then propose the formation of tribes, gangs? Not exactly, because the commune is different from the community; it does not live closed off and isolated from the world—in which case it would simply dry up and die—but it is always attentive to what escapes and overflows it, in a positive relationship with the outside. Neither means for an end, nor ends in themselves, communes follow a logic of expansiveness, not of self-centeredness.

Are they talking about local, neighborhood politics? Again, not exactly, because the territory of the commune is not previously given, it does not pre-exist, but it is the commune itself that activates it, creates and draws it—while, in turn, the territory offers it shelter and warmth. The commune’s territory does not have bounded limits: it is a mobile and variable geography, in permanent construction.

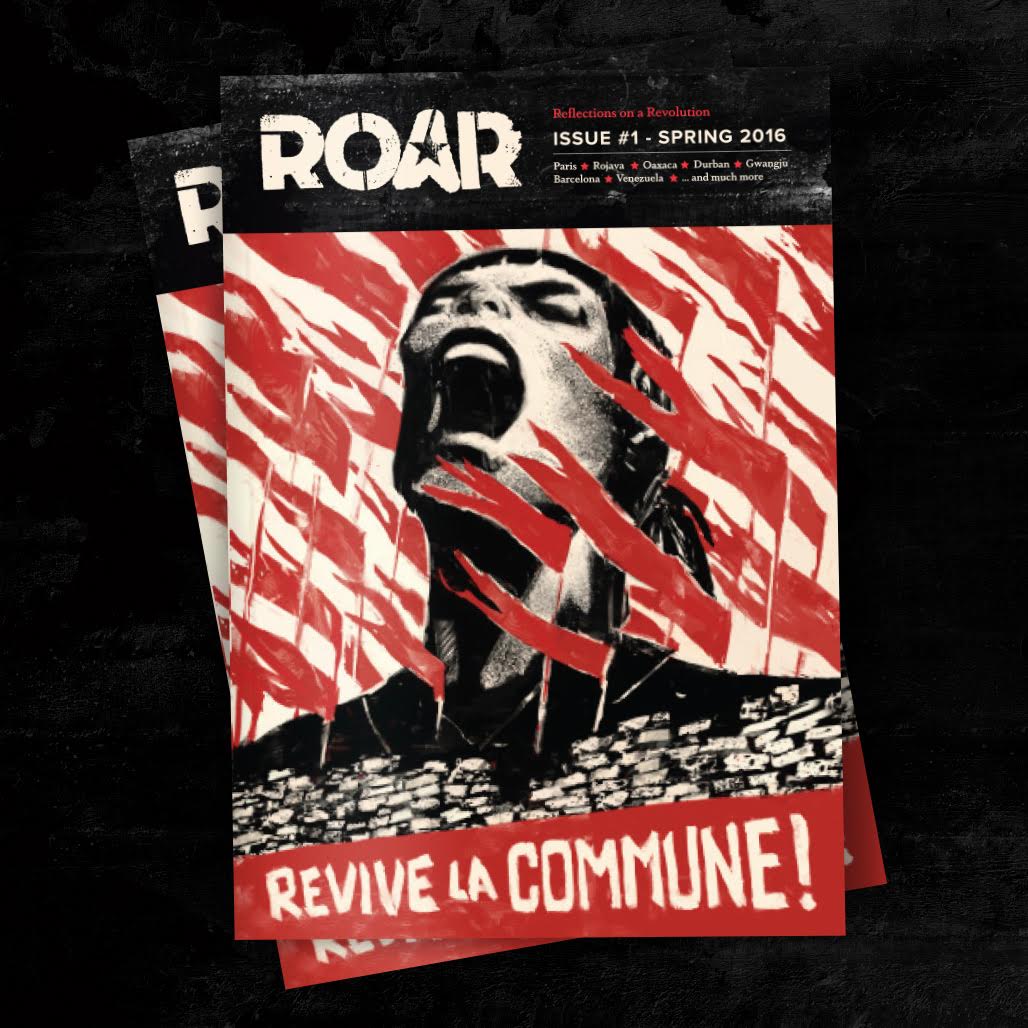

Subscribe to ROAR now to receive our first print issue on the commune.

A group of friends can be a commune, a cooperative can be a commune, a political collective can be a commune, a neighborhood can be a commune. The problem of organization is, therefore, the problem of thinking how the heterogeneous circulates, not how the homogeneous is structured. The challenge is to invent forms and apparatuses of translation, moments and spaces of encounter, transversal ties, exchanges, opportunities of cooperation, and so on.

The “universal” is not constructed by putting the particular (the situated, the singular) in parenthesis, but by deepening, by intensifying the particular itself. The entire world is already in each situation, if we give ourselves time to look for it. It would be difficult, for example, to think of an experience with greater capacity of interpellation, one that at the same time is so deeply inscribed in a very concrete territory, as Zapatismo. As the poet Miguel Torga says, “the universal is the local without the walls.”

The most important “organization” is, ultimately, everyday life itself—as a network of relationships capable of being activated politically here or there. The denser the network, the better the quality of those relationships, the greater the revolutionary potential of a society.

6. In praise of touch

Revolutions have also been thought and carried out from the paradigm of government: the subject against the world—the vanguard—that pushes it in a good direction; thought as science and Knowledge with a capital K; action as the application of that knowledge; reality as shapeless matter to model; the revolutionary process as the “product” or fine adjustment between means and ends, and so on.

In the paradigm of government, being a militant implies always being angry with what happens, because it is not what should happen; always chastising others, because they are not aware of what they should be aware of; always frustrated, because what exists is lacking in this or that; always anxious, because the real is permanently headed in the wrong direction and you have to subdue it, direct it, straighten it. All of this implies not enjoying, never letting yourself be carried away by the situation, not trusting in the forces of the world.

There could be another path. Learning to fully inhabit, instead of governing, a process of change. Letting yourself be affected by reality, to be able to affect it in turn. Taking time to grasp the possibles that open up in this or that moment. It is in this sense that the Invisible Committee states that “touch is the cardinal revolutionary virtue.”

If revolution is the increase of the potentialities inscribed in situations, contact (con-tacto—“touch with”) is simultaneously that which allows us to feel where potential is circulating and how to accompany it without forcing it, with care. And it is this sensibility that we need more than a thousand courses of formation in political content.

“Strategic intelligence is born from the heart… Misunderstanding, negligence and impatience: there is the enemy.”

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/invisible-committee-revolutionary-question/

Next Magazine article

Consolidating Power

- David Harvey

- December 9, 2015

After the Water War

- Oscar Olivera

- December 9, 2015