Poetry from the Future

- Issue #9

- Author

In Chiapas, the Zapatistas are expanding their system of autonomous self-governance into new villages for the first time in twenty-five years. Since 2012, the people of Rojava have reorganized their society around communes and cooperatives from the neighborhood level up, all the while facing extraordinary threats of extermination. Assembly democracy movements in Barcelona, A Caruña, Jackson, southeastern Turkey and elsewhere have swept into local office via popular municipalist platforms.

This past September, delegates from community organizations from around Mexico, the United States and Canada gathered in Detroit for the Congress of Municipal Movements to launch a North American confederation of radical democracy initiatives. Each of these initiatives and so many more are seeking to reshape the world from below.

At the same time, right-wing authoritarian leaders and the rise of fascist militancy are threatening democracy around the globe. The next financial crisis, this one possibly even more devastating than the last, may be just around the corner. And the global climate emergency, without a doubt the greatest challenge confronting humanity today, is actively undermining the liveability of our planet.

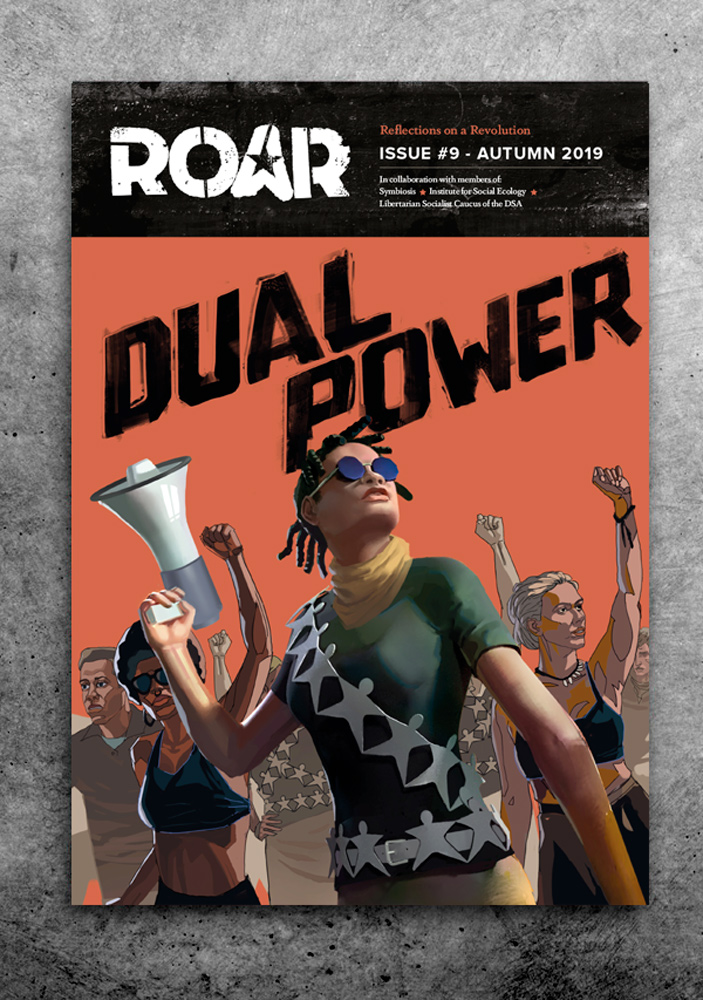

Where does this leave us? As a fresh wave of popular revolt washes over the globe, the fundamental questions of how revolutions happen, and how emancipatory outcomes result, are suddenly concrete concerns for organizers and movement builders. In this changing international environment, the current ROAR issue — “Dual Power” — presents a strategic vision for a libertarian socialist politics in 21st-century North America.

Only by building directly-democratic spaces and institutions at the local level, and confederating them to form the “commune of communes” both nationally and internationally, can our insurgent movements bring down and replace the governing institutions of the current system.

Movements, generally speaking, are understood in terms of their issue or site of struggle: the labor movement, the housing movement, the environmental movement, the immigrant rights movement. This habitual categorization in terms of “what they are fighting for” is useful as far as it goes, but it can obscure other quite fundamental distinctions. There are radically different means of building power in the workplace, or fighting climate change, or advocating for tenants’ rights, and there are radically different ends to which that power can be directed.

Movements, generally speaking, are understood in terms of their issue or site of struggle: the labor movement, the housing movement, the environmental movement, the immigrant rights movement. This habitual categorization in terms of “what they are fighting for” is useful as far as it goes, but it can obscure other quite fundamental distinctions. There are radically different means of building power in the workplace, or fighting climate change, or advocating for tenants’ rights, and there are radically different ends to which that power can be directed.

In this issue of ROAR, we will be examining a number of different bottom-up movements — from cooperatives to labor, climate justice to housing — that are nevertheless movements of the same type, working to institutionalize popular power outside the state towards a revolutionary politics of dual power.

It is this expansive understanding of democracy that is necessary to win the future: to provide for all people, guarantee equality for all races and genders, and protect our ecosystems and our planet.

Having so little power ourselves, and with capital on the move, the left in the neoliberal period has typically centered resistance to power. The movements to be discussed in this issue, by contrast, embrace the fusion of what we might call “oppositional politics” and “reconstructive politics.” Their work involves resistance, of course, but that resistance is channeled into building power, vesting it in new institutional forms organized according to principles of direct democracy to lay the groundwork for an entirely new sort of society. This is a very different sort of response to the powerlessness of ordinary people.

Any useful analysis of the present crisis has to begin with and come to terms with this present powerlessness. Human civilization is not butchering, bulldozing and burning its way through the ecological conditions of its own existence because human beings are irrational locusts unconcerned with their own survival — quite the contrary, this destructive social system is only able to continue because the vast majority of us are denied any say in how it operates. All core decisions of production, investment, technology and infrastructure are out of our hands entirely.

Political decision-making is insulated from the public at large through governments organized around elite rule, periodic elections notwithstanding. If we are to pull back from the brink and redeploy our collective creativity and intelligence towards repairing the living fabric of our world, there must first be power in the hands of ordinary people: campesinos and workers, neighbors and tenants.

Power means collective action, through which people have the ability to do or change things. Today, power means the few directing the activity of the many, shored up through threat of violence or privation. Tomorrow, it must mean making decisions together and carrying them out together. The task for today’s revolutionary movements is to supplant the dominant institutions that disempower and isolate us and put our labor in the hands of others with new ones that uphold the commons and cement our power over our own shared lives.

The movements this issue will explore are themselves vibrant laboratories of social experimentation, each inventing, adapting and scaling new sorts of institutions through which people can live, work and decide together. Some such institutions, like popular assemblies and producer cooperatives, have blossomed through mass movements (and movements through them) across history. Others have been made possible only through new technologies or relatively recent reforms, like platform cooperatives, community-owned fabrication labs and community land trusts. All of them, we must hope, will help assemble the future.

The movement-building function of such institutions, especially for those within bottom-up movements which explicitly understand themselves to be revolutionary, has a clear trajectory.

First, these institutions can address our deprivation under capitalism. Impoverished people all over the world turn to mutual aid as an alternative to the individual struggle for survival. The mosaic of community institutions like rotating savings and credit associations, community gardens, time banks, neighborhood patrols and tool libraries is an essential part of working-class response to shrinking social safety nets and economic contraction. Meeting these basic needs is a precondition for engaging the poorest among us in political struggle. This is not just a response to material poverty, but to social poverty as well. With these institutions, people can come together and foster human connection that we are otherwise denied.

Second, these institutions can be vehicles for channeling broad-based, popular struggle against systemic harms. Popular struggle takes collective action, which takes organization. A neighborhood assembly, for instance, that has developed its political credibility and structures of community decision-making through small-scale solidarity economy practices can also channel that collective action into oppositional campaigns. My own block club in Detroit began as a group of neighbors working together to chase off illegal dumpers and organize community clean-ups, and through base-building and mobilizing residents we have since been able to halt the city’s efforts to bring polluting factories into our neighborhood without our input. Other block clubs have transformed themselves into powerful vehicles for neighborhood resistance to gentrification and displacement.

As crises intensify, powerful anti-capitalist resistance will need to rise to meet them, requiring this sort of mass organization of ordinary working people on a huge scale. Such oppositional movements may crystalize around positional reforms, to give us more breathing room to fight for more transformative demands, or they may be waves of unrest and open rebellion. In either case, effective and sustained oppositional power organized through these institutions of genuine democracy can come to constitute a base of popular power outside the state.

Third, genuinely democratic institutions can actually replace those of the present system, overthrowing the social forms of hierarchy and domination. This is what we call a dual power vision of revolutionary change.

Our political practice today can prefigure the world to come, being a consciousness-raising illustration of how things could be different. But organizing for dual power is a step beyond the propaganda value of prefigurative politics. We can think of this approach as the preformation of the liberated society, the actual development of its future governing institutions in the here and now. This is, in part, why these movements are so insistent on implanting the most robust democratic principles at every level of their political practice. They are the seeds of a new world, taking root here in the shell of the old.

In the most revolutionary settings, we can see assemblies and councils of participatory democracy federating together into a new government, a new kind of government — of, by and for the people. The old social order of rule from above has had its authorities dissolved into the bodies of face-to-face democracy that we ourselves have created. This is what we seek to bring about for every level of social organization and activity.

That vision is our movement horizon. It may not always begin with stunning confrontations with the powers that be — instead, turning out neighbors to a block meeting, digging up a vacant lot for a community garden, holding intentional trust-building conversations with co-workers — but there is still power in those first steps. We need only visionaries and revolutionaries embedded in these different sites of common life and common struggle, taking those unglamorous first steps and able to point to where they might lead.

The essays that follow trace this trajectory across a great diversity of radical movements. When people come together around common interests, we see not only the potential for extracting concessions from those who actually govern our world, but also the building blocks of a new system of governance altogether. These thinkers and organizers are fiercely at work with their hands, with their hearts, with their imaginations, creating our world anew. As Murray Bookchin once wrote, “The revolutionary not only attacks the forms created by the legacy of domination, but also improvises new forms of liberation which take their poetry from the future.”

Those poets in this issue spin verse after living verse of what could be, and make it so.

Note from the editor — This issue of ROAR was produced in close collaboration with members of Symbiosis, the Institute for Social Ecology and the DSA – Libertarian Socialist Caucus. Special thanks to Francis Tseng, Simone Chen and Brontë Wieland for their editorial support.

Visit our Patreon page to download the “Poetry From the Future” wallpaper.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/poetry-from-the-future/

Next Magazine article

Let’s Talk About Democracy. Real Democracy.

- Cora Roelofs

- December 22, 2019

The Confederation as the Commune of Communes

- Debbie Bookchin, Sixtine van Outryve

- December 22, 2019