The European Reaction

The growing threat of authoritarianism demands mass movements and broad-based anti-fascist action on the basis of internationalism and genuine solidarity.

A Dozen Shades of Far Right

- Issue #5

- Authors

Earlier this year, a site in the German city of Dresden that had originally been designated for a refugee shelter was turned into a court room. Ironically, it now hosts a terror trial against eight members of the far-right Freital Group, who are accused of carrying out a series of bomb attacks against migrants and anti-fascists in Germany.

In recent years, the Saxon city of Freital gained notoriety for its anti-refugee mobilizations, its racist vigilance and its clandestinely coordinated right-wing militancy. Within spitting distance of the town, the Pegida movement has been mobilizing against the “Islamization of the West” every Monday for over two years now. The situation in Saxony epitomizes an ongoing surge of far-right activity not only in East Germany and the entire Republic, where over 3,500 attacks on migrants took place in 2016 alone, but all over Europe.

The Rise of the European Far Right

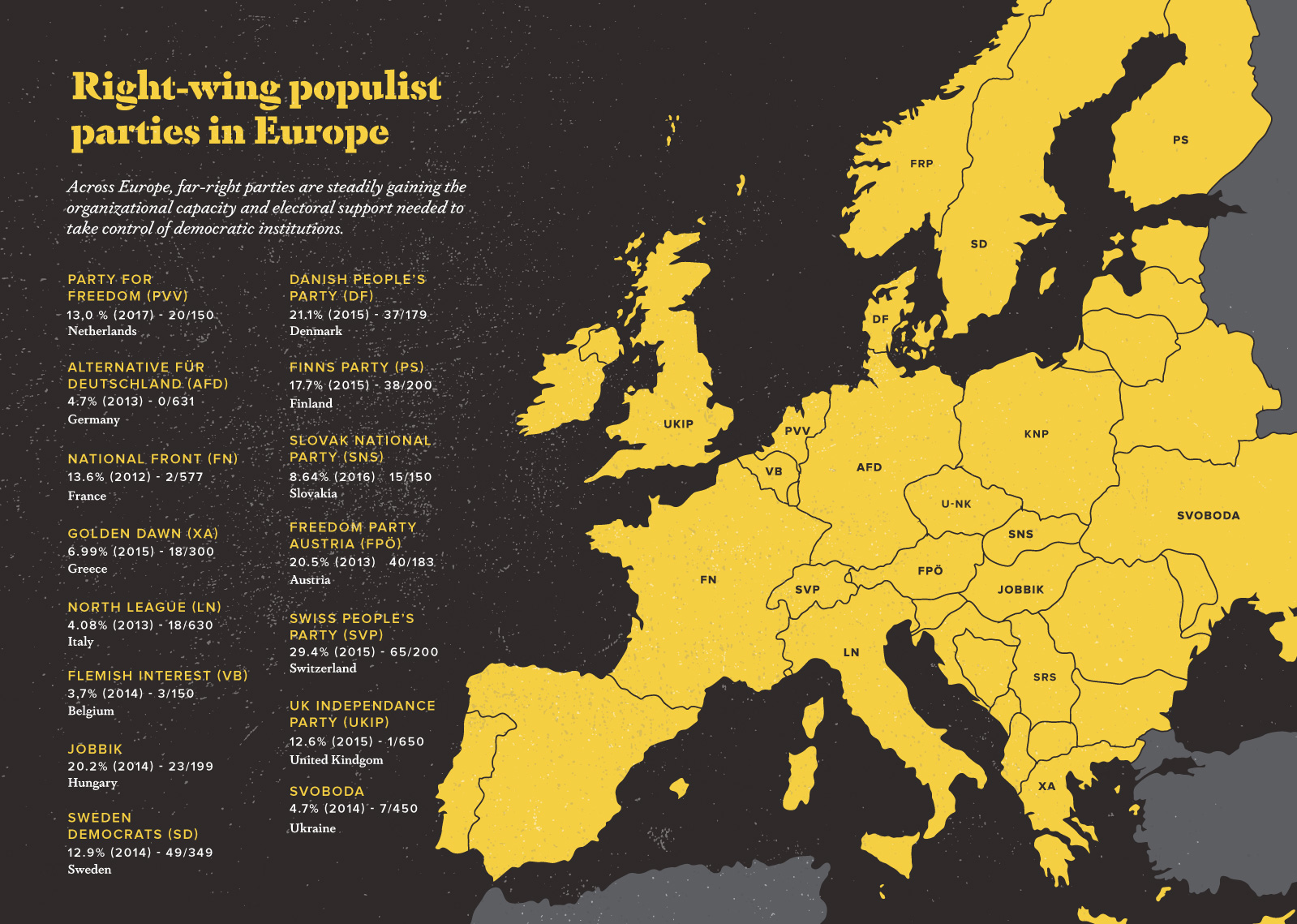

Across Europe, far-right parties are steadily gaining the organizational capacity and electoral support needed to take control of democratic institutions. At the same time, extreme-right militias are attempting to reclaim the streets, while New Right “intellectual” circles have been pursuing a long-term strategy of setting the cultural stage for an authoritarian transformation of European societies. These multifaceted manifestations of the shift to the right all find their moment suprême in the confluence of the economic crisis and the so-called refugee crisis.

Most anti-fascist analyses therefore draw a direct line between the outbreak of the global financial crisis and the rise of the far right. “Capitalist crisis breeds fascism,” goes the oft-repeated battle cry — especially in countries that have borne the brunt of brutal austerity measures in recent years. There is indeed little doubt that the temporal acceleration and parallel appearance of similar right-wing phenomena should be considered within its appropriate economic context. Yet in the effort to detect the root causes of the far right’s ascendance, we should avoid falling back on overly simplistic explanatory schemes.

While the crisis has undoubtedly catalyzed far-right mobilization, the growing popularity of right-wing parties and movements ultimately rests on widespread racist attitudes and petit-bourgeois anxieties about social status that have existed at all times and places. Examples like Portugal and Spain show that crisis-ridden societies do not automatically drift to the right. Some far-right actors have been more successful than others in transforming socio-economic grievances into ethnic tensions. Beyond the structural dynamics driving the authoritarian turn of capitalist democracies, we should therefore also pay close attention to the differential capacities, mobilization strategies and immediate crisis responses of the far right, which have fundamentally changed in recent years.

While the crisis has undoubtedly catalyzed far-right mobilization, the growing popularity of right-wing parties and movements ultimately rests on widespread racist attitudes and petit-bourgeois anxieties about social status that have existed at all times and places. Examples like Portugal and Spain show that crisis-ridden societies do not automatically drift to the right. Some far-right actors have been more successful than others in transforming socio-economic grievances into ethnic tensions. Beyond the structural dynamics driving the authoritarian turn of capitalist democracies, we should therefore also pay close attention to the differential capacities, mobilization strategies and immediate crisis responses of the far right, which have fundamentally changed in recent years.

It goes without saying that far-right politics are not a new phenomenon. Anti-fascists from all over Europe have been struggling for years to expose, contain and subvert neo-fascist tendencies through a variety of means. The threat of a far-right resurgence long lured at the margins of the electorate, but today various far-right forces are establishing themselves in different strata of society. This is a trend that no one was really prepared for.

New Forms of Far-Right Activism

The far right was once relatively easy to detect. Most organizations and activists gravitated around one political party that unified different tendencies during election time and that acted as representative of a broader far-right field. Despite existing frictions between different currents, open conflict was usually avoided. Nowadays, by contrast, far-right activism is extremely diversified, decentralized and internally divided in terms of strategy and practices. Moreover, due to personal and political disputes, the European far right has been characterized by multiple schisms.

In recent years, stagnating popularity, inflexible hierarchies and unoriginal policy ideas caused many on the far right to look towards new forms of activism as well as the integration of ideological fragments that were once alien to the right. As a result, the modes of interaction between different players tend to oscillate between conflicting priorities. At the one end, there is the inevitable competition for scarce resources, including money, facilities, labor and adherents. At the other, there is a division of labor that obliterates differences in ideological and organizational matters. Moreover, by blurring the boundaries between (and within) different far-right organizations, the latter manage to deliberately sow confusion about the core of far-right ideology and action.

One striking example of this phenomenon is the Identitarian Bloc that emerged in France in 2012 and subsequently spread to other European countries. Their direct action approach and spectacular interventions against the symbols of Islam and the political establishment are hardly compatible with the more serious political style of the Front National. Nevertheless, as their respective discursive tendencies and personal collaborations attest, even these two organizations are in close contact with one another, and it is obvious that there is a certain degree of coordination between them.

There are other hybrid actors that act simultaneously in different arenas. Looking at Golden Dawn in Greece, for instance, we can see how quickly a tiny neo-Nazi association managed to advance to become the country’s third strongest party. Against its many opponents, Golden Dawn succeeded in integrating different forms of nationalist activism into its ranks and ultimately gaining hegemony in a heterogeneous far-right field. Beside close relationships with state institutions, especially the police and judiciary, this locally based activism provided the basis for the party’s penetration into mainstream segments of society — without abandoning its more militant adherents.

Another important notion when discussing the contemporary far right is that of “populism.” Leaning on a strong element of polarization between a “pure” native people and a corrupt establishment, right-wing populism capitalizes on the public’s deep-rooted mistrust of political elites and representative institutions. Presenting themselves as the incarnation of “the people,” far-right parties have managed to accumulate more votes and legitimacy.

However, the use of populistic elements is neither a new strategy nor a useful criterion to distinguish more dangerous right-wing actors from less dangerous ones. In fact, it is precisely where right-wing populists are in power — as in Hungary, Poland, Turkey and the United States — that neo-fascist forces have been on the rise. The propensity to downplay the dangers of right-wing “populists” in the media and academia is inevitably connected with the changing relationship between the far-right and the mainstream.

The Far-Right (and the) Mainstream

It is no secret that mainstream and far-right politics are somehow connected. For a long time, the political mainstream at least drew a clear discursive line between “acceptable” forms of claims-making and far-right propaganda. Today, it is controversial to what extent such a “cordon sanitaire” ever really existed — or if it was always just a bourgeois self-legitimation myth.

Taking the Austrian coalition of the conservative ÖVP and the far-right FPÖ in the early 2000s as an example we can see that this figurative firewall between the far right and the mainstream has always been porous. More recent political constellations in Denmark, Norway and Switzerland could be invoked here as well. The power calculations of the ruling class most often outweigh moral considerations about far-right actions and ideas.

This rightward shift in mainstream politics was to a certain degree self-induced. Representatives of the political center voluntarily opened Pandora’s box with unnecessary discursive transgressions. The German social democrat Thilo Sarrazin is a case in point. In his bestselling book of 2010, Sarrazin complained about the fertility of Muslims in Germany, which he claimed lowered average intelligence levels and created a migrant underclass completely dependent on the welfare state. Back then, surveys revealed that more than 20 percent of the population would vote for a party championing his position. Today, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party reaps the fruits of this earlier taboo-breaking by representatives of the political mainstream.

Nevertheless, the far-right perspective on the political mainstream remains ambiguous. The constant maneuvering between a blatantly racist dialogue among cadres and subdued outward messaging to potential voters portends a two-fold strategy: on the one hand, far-right actors try to assume ownership over contentious issues that are broadly discussed and accepted, hence taking a dissident position to set themselves apart from the “systemic” parties of the “establishment.” On the other hand, they aspire to be accepted as a legitimate alternative to the established right-wing parties, touting for the same political support structures and longing for positive feedback from the media.

Three Overarching Currents

So what mobilizes voters and supporters of the far right? In today’s political constellation, at least three classical conservative themes can be identified that are prone to being radicalized by the far right.

First, a strong anti-feminist current is apparent in the attempt to roll back recent advances in women’s and LGBTQ emancipation and bring about a return towards traditional gender roles. Under the umbrella of broad campaigns like the manifs pour tous in France, different currents of the far right converge with conservative adherents to build coalitions that transgress traditional boundaries between the socially acceptable and far-right ideology. It is debatable to what extent this effect is strategically calculated and perhaps the principal intention behind these mobilizations.

Oftentimes, religious fundamentalists fulfill the role of a transmission belt in this intermediation between the far right and conservatives. Lamenting the debauched norms of modern society, they advocate a spiritual return to a more hierarchical form of community that supposedly protects believers from external dangers. As the smallest cell of the nation, the family is propagated as the prototype of cohabitation, safeguarding the members of an imagined autochthonous community. Sexism is an inherent element of most forms of nationalism. The social role of women is mostly confined to reproducing the body of the nation — by bearing, raising and educating its children.

Directly intertwined with this is the absurd idea, which existed long before the most recent arrival of refugees in Europe, that ethnic minorities endanger this homogeneous body of the nation. The fear of mingling between different “races” and the extinction of the “autochthonous people” as a supposed consequence reveals the obsession with ethnic purity that all far-right actors have in common. Marginalized communities like the Roma, for instance, are presented as scapegoats for their supposed criminality or refusal of work. Targeted as an “enemy within,” marginalized communities serve to project petit-bourgeois fears of a loss of social status amidst the vagaries of the market.

The alleged “Islamization” of Europe rounds up the two aforementioned patterns with a strong anti-Muslim component. The idea of a “healthy nation,” connected with conspiracy theories about its decay, is again at the center of concern here. New Right thinker Renaud Camus presents a theory of “the Great Replacement” that received widespread attention among different far-right currents. The idea is that the “colonization” of Europe by Muslims is a deliberate political project pursued by the establishment to consolidate its power by uprooting national consciousness.

With the first Pegida demonstration in Germany in late 2014, the far right’s Islamophobic ideas were transformed into a platform for open hatred against Muslims, and eventually served as a paragon for anti-Islam mobilizations across Europe. Animated by the so-called refugee crisis that took off in earnest in 2015, the far right joined forces to radicalize public discourse on Islam and migration. Islam, in all its varieties and complexities, is presented as one coherent and fundamentally violent political ideology, and Muslims are accused of aspiring after world dominance.

This anti-Muslim rhetoric clearly features key elements of the classical anti-Semitic narrative structure. At the same time, assaults on Jews continue to regularly take place all over Europe. In fact, the far right’s ideological flexibility allows for anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim prejudices to exist side by side.

Nationalists Organizing Transnationally

In contrast to their foundational nativism, far-right politics do not stop at the borders of the nation-state. In fact, the supposedly nationalist far right needs to be conceived of as a transnational challenge to notions of social emancipation. Although it is certainly rooted in a national context, it can hardly be understood without its continental European — and even global — dynamics.

Far-right groups mostly build upon a common ethno-pluralistic concept that envisions a kind of “global apartheid” based on the spatial segregation of national cultures that deny the existence of any internal factions or class divides. The identification of common enemies, the opposition to the technocratic EU bureaucracy, and the framing of social conflict in ethnic terms all go back to the shared principles of nativism and authoritarianism, which create a mutual framework for far-right discourse and action across national boundaries.

Transnational cooperation among different far-right groups can take a variety of forms. Formal party alliances can be observed in the European Parliament, for instance, like in the case of the European People’s Party, where German conservatives from CDU/CSU work together with the Hungarian Fidesz of Viktor Orbán. Beyond such obvious surface manifestations, however, far-right activists have maintained strong underground ties for decades. In terms of street-based action, a new surge of international travel is supposed to generate greater coherence between far-right groups in different countries. Meetings crystallize around large-scale demonstrations in Sofia and Athens or commemoration gatherings in Rome, Paris and Riga, which are part and parcel of the agenda of European nationalists and neo-Nazis.

As a festival in Switzerland with more than 5,000 participants affiliated to the Blood and Honour network illustrates, we should not neglect the recovery of subcultural forms of cross-border exchange either. The revelation of the German National Socialist Underground, responsible for the targeted killing of nine migrants, underlines that militant splinter groups like Combat 18, which initially operated in Britain, still serve as important organizational blueprints for clandestine activism.

Another role model that received growing attention from European nationalists are vigilante groups operating on a semi-legal level and sometimes even in close cooperation with the police. The Soldiers of Odin, for instance, were among the most visible formations harassing the Muslim population in Finland, and received broad popular support to patrol the streets of Helsinki. Spin-offs in other Scandinavian and Central European countries soon followed, and won even greater approval following the hotly debated sexual assaults against women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2016.

Similarly, vigilante groups in Hungary and Bulgaria are taking action to “protect” their countries’ borders against migrants and refugees. These transnational interactions also proceed on a more subtle level because there are no direct connections between the different actors, making it harder to see how the ideas of far-right activists in one place can inspire the actions of their counterparts in another, how new practices are learned and discourses adopted, and how certain symbols and codes diffuse across borders and contribute to a communal spirit of belonging among various nationalist groups.

It is remarkable, in this respect, how far-right actors build on developments in other countries to construct a far-right success story. The likelihood of more and more parties making gains in national elections and even taking state power contributes to the notion of a far-right winning streak. The growing discursive overlap and mutual exchange of strategies between different groups demand a European analytical framework. It also requires a Europe-wide — even global — response by anti-fascists.

Implications for Anti-Fascist Praxis

As increasing state repression coalesces with the resurgence of the far right, anti-fascists in Europe and the United States struggle to get a grip on the situation. In some countries, new anti-fascist groups and mobilization patterns are emerging. In others, they stagnate or collapse. There is certainly no overarching template on how to confront the various challenges we now face.

In concrete terms, there is no way to circumvent a physical confrontation with the far right’s appropriation of space at the local level. Anti-fascists have a broad repertoire of direct action methods to prevent the establishment of “no-go areas” for migrants and to defend spaces against far-right invasion. In the same vein, specific tactics like anti-fascist motorcycle rallies have proven a useful means to break far-right hegemony over core districts in cities like Athens.

Such event-based anti-fascist mobilizations will now have to merge with everyday practices and action. This means that social (infra-)structure must be built on the local level to generate quick response capacity. Social centers and other self-organized activities need to evolve as points of convergence for activists and — more importantly than ever — as attractive spaces for non-activists, allowing the anti-fascist resistance to engage with a broader public in the neighborhoods.

Once the far right crosses a certain threshold of relevance, however, intervention becomes more and more difficult, and the potential leverage points for intervention begin to shift. The concentration of votes and supporters gives far-right parties a certain legitimacy in the public sphere. Given their self-identification as the “discriminated outsiders” or the “victims” of a decadent system, the unilateral targeting of far-right groups may end up backfiring. Anti-fascists need to consider this very carefully. They certainly cannot succeed without tackling the broader political order that is responsible for the far right’s recent resurgence.

An anti-fascist critique is a critique of the whole. It is about building a counter-hegemony based on class solidarity and mutual aid, in strong opposition to any form of racism, sexism and authoritarianism, including oppressive ideologies like Jihadism. Reactionary politics have to be contested regardless of who propagates the respective ideas. We need to articulate our ideas and thoughts in ways that offer people concrete alternatives to cope with everyday economic misery and social alienation. Anti-fascism always requires a positive vision of the social, and cannot just react to external threats alone. Resistance must begin at the grassroots, involving direct action in our workplaces, schools and universities, but also conversations with our families and neighbors.

All too often, anti-fascism remains within the sphere of a closed activist scene, with its own particular subcultures and sporadic mobilizations. The growing threat of an authoritarian transformation of our societies now demands mass movements and broad-based anti-fascist action — diverse and transnational in nature, but always on the basis of genuine solidarity.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/rise-european-right-wing-politics/

Next Magazine article

Radical Democracy: The First Line Against Fascism

- Dilar Dirik

- April 2, 2017

Anti-Fascism and Revolution

- Alexander Reid Ross

- April 2, 2017