Public Finance

The concentration of the US public debt in the hands of the 1 percent has contributed to inequality and presents a fundamental threat to democracy.

The Rise of the American Bondholding Class

- Issue #3

- Author

The history of class conflict, power and inequality in the United States has always been intimately bound up with the public debt. Already during the War of Independence (1775-‘83), revolutionary forces accumulated debts of $54 million, and a difficult task for the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, was to devise a plan to manage these liabilities. Should the Federal Government try to repay its debts in full? If so, by what means should it honor its commitments to creditors?

Defaulting on foreign debts was out of the question. The French and the Dutch contributed roughly one-quarter of wartime financing, and the United States did not want to alienate itself from allies that assisted its drive for independence. At the same time, the Federal Government was hesitant to renege on its commitment to domestic bondholders. A small but powerful group of men, including most of the architects of the Constitution, provided the remaining funds to finance the war. These men would rally against default and would push for a tax system that raised reliable revenues to service the public debt. This system would prove especially advantageous if the tax burden were to fall on someone else — that someone else being the vast majority of Americans who did not own government bonds.

In the end, Hamilton decided that the debts were to be repaid in full. And in order to raise the revenue needed to repay its debts, the US Congress approved Hamilton’s proposal to levy a highly regressive excise tax on distilled spirits. Small-scale farmers saw the new tax as a threat to their livelihood and vented their frustrations through violent attacks against tax collectors in western Pennsylvania. So concerned was Hamilton with the unrest caused by the resultant Whisky Rebellion of 1794 that he personally accompanied General George Washington, and the 13,000 troops he commanded, to put down the rebellion. One critic, William Findley, seized on the events, suggesting they were proof that Hamilton’s system of public debt had created a “new monied interest” that wanting nothing other than “oppressive taxes.”

Mapping the Bondholding Class

Early critics were suspicious of Hamilton’s plan. They saw the public debt, and the broader system of public finance of which it was a part, as a culprit of worsening inequality and social instability. And today, well over two centuries later, the public debt remains a major source of controversy in American politics.

Some continue to suggest that government bonds are still concentrated in the hands of the rich and powerful. Others insist that government bonds are widely held amongst small savers, even widows and orphans, and help to democratize the financial system. And yet, despite centuries of contestation, neither side has managed to produce much evidence to support their claims. This is a serious oversight. The US public debt now stands at roughly $18 trillion dollars, making it one of the largest and most liquid financial markets in the world. An absence of reliable data on its ownership structure means that we have little understanding of the power relations that underpin this vital component of global finance.

My new book Public Debt, Inequality, and Power: The Making of a Modern Debt State (California University Press) intervenes into this longstanding but muddled debate. The book unearths some uncomfortable facts about whose interests are really served by the public finances during this crisis-ridden age. In particular, my analysis reveals a rapid rise of a “bondholding class” of wealthy households and large financial corporations over the past few decades.

Since the early 1980s, and especially since the onset of the global financial crisis, there has been a rapid concentration in domestic ownership of the public debt. Specifically, the stunning increase in concentration has taken place in favor of the now-infamous top 1 percent of US households and the top 2,500 US financial corporations. Distribution of the public debt is tightly correlated with the distribution of wealth more generally. In other words, when the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent and large corporations increases or decreases, so too does their share of the public debt.

Figure 1 illustrates this dynamic. What is most remarkable is the massive increase in concentration of the public debt that has taken place since the onset of the crisis. From 38 percent in 2007, the top percentile’s share the public debt has climbed to a shocking and unprecedented 56 percent in 2013, the last year for which data are currently available.

A similar dynamic characterizes corporate ownership of the public debt. Over the past three and a half decades, the top 2,500 U.S. corporations have increased their share of corporate holdings of the public debt from 65 percent in 1977-‘81 to 82 percent in 2006-‘10. Much like the household sector, corporate concentration has intensified since the onset of the crisis. In 2006 the top 2,500 corporations owned 77 percent of the corporate share of the public debt and climbed to 86 percent by 2010. Crucially, these corporate holdings of the public debt are increasingly dominated by mutual funds, which are owned predominantly by the top 1 percent, at the expense of widely owned pension funds.

Overall, I argue that the spectacular increases in the public debt since the early 1980s have served the interests of a bondholding class of dominant owners at the apex of the wealth and income hierarchy. How do we explain these massive increases in public debt? And how exactly do we explain the connection between growing inequality and rising public indebtedness? Answers to these questions can be found in Wolfgang Streeck’s concept of the “debt state.”

The Making of a Modern “Debt State”

In his book Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism (Verso), Streeck traces a shift in the advanced capitalist countries from a “tax state” to a “debt state.” Under the post-war tax state, gradual increases in government expenditures were matched by tax revenues, which resulted in falling levels of public indebtedness. With the emergence of the debt state from the 1970s onward, government expenditures have continued to grow while tax revenues have stagnated, resulting in escalating levels of public indebtedness.

The US is, in many ways, the ultimate manifestation of the debt state, where stagnating federal tax revenues have been the primary driver of increases in the public debt. Tax stagnation is itself the product of a successful tax revolt on the part of powerful elites. What this means is that tax revenues constitute a dwindling portion of national income, and also that the bondholding class is now paying less and less taxes as a percentage of its total income.

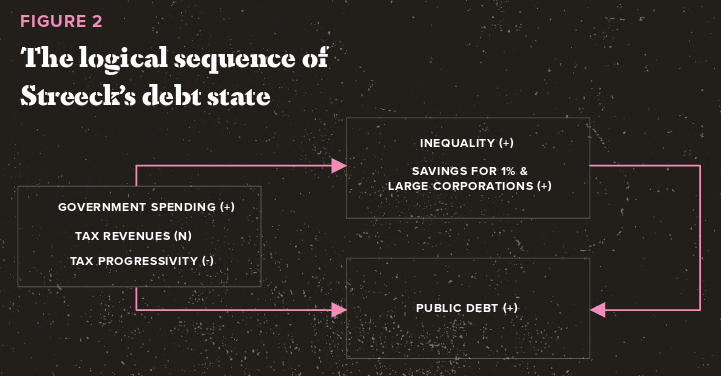

Declining tax progressivity means, by definition, greater inequality and increased savings for those at the top of the wealth and income hierarchy. As a result of changes to the tax system, elites have more money to invest in the growing stock of US Treasury securities, which, thanks to their “risk-free” status, become particularly attractive in times of crisis. The logical sequence of the debt state is outlined in Figure 2.

In essence, what the transition from the tax state to a debt state means is that the Federal Government chooses to borrow from the bondholding class rather than taxing it. And in deciding to furnish wealthy households and large corporations with risk-free assets instead of levying taxes on their incomes, the debt state reinforces the existing pattern of inequality. This raises further questions about the long-term stability of current arrangements. The debt state is likely to persist into the foreseeable future, and the reason has to do in large part with the role played by foreign ownership of the public debt.

In essence, what the transition from the tax state to a debt state means is that the Federal Government chooses to borrow from the bondholding class rather than taxing it. And in deciding to furnish wealthy households and large corporations with risk-free assets instead of levying taxes on their incomes, the debt state reinforces the existing pattern of inequality. This raises further questions about the long-term stability of current arrangements. The debt state is likely to persist into the foreseeable future, and the reason has to do in large part with the role played by foreign ownership of the public debt.

A Powerful Foreign Bond

Since the early 1970s, there has been a rapid globalization of the US Treasury securities market. In the post-war period, official and private foreign investors consistently owned less than 5 percent of the US public debt. The foreign share has climbed steadily ever since and at the present time stands at roughly 50 percent.

This seemingly insatiable foreign appetite for US Treasury securities means cheaper credit for the US government, which deflects challenges to domestic owners of the public debt at the top of the wealth and income hierarchy. In the case of the Federal Government, cheap credit relieves pressures for socially disruptive spending cuts, as well as increased taxation, which would fall more heavily on elites. Access to cheap credit also dampens resentment toward those same elites by allowing low- and middle-income Americans to maintain consumption habits in the face of decades-long wage stagnation.

At the same time, foreign owners have something to gain from the existence of a domestic bondholding class. Foreign investors, especially China, fear that the Federal Government will “print money” to inflate away its growing debt burden. But the existence of a powerful group of domestic owners invested in the creditworthiness of the Federal Government should help to alleviate these fears. The wealthy households and large corporations that dominate domestic ownership of the public debt hold considerable sway within the political system and provide a powerful check against policies that might compromise the risk-free status of US Treasury securities.

A formidable “bond” of interests therefore unites foreign and domestic owners of the public debt. In relieving domestic tensions engendered by growing inequality, this bond of interests works to reinforce the status quo of the debt state. In helping to sustain foreign confidence in US Treasury securities, this bond also helps to sustain US financial power in the global political economy.

Consequences for Democracy

What, then, can we say about the consequences of growing concentration in ownership of the public debt? Why exactly does it matter? Addressing these questions leads us to the question of power.

Throughout history a widely held public debt was thought to be good for democracy and social cohesion, making wide swathes of the population feel quite literally invested in government. An unequally distributed public debt, however, has been seen as a threat to democracy, increasing the power of a tiny group of owners at the expense of the rest of the polity. The prevailing sentiments are captured in the following passage from former Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., who promoted widespread ownership of the public debt during World War II:

Every man and woman who owned a Government Bond, we believed, would serve as a bulwark against the constant threats to Uncle Sam’s pocketbook from pressure blocs and special-interest groups. In short, we wanted the ownership of America to be in the hands of the American people.

The linkages that Morgenthau Jr. draws between the public debt, power and democracy have obvious intuitive appeal. And Streeck’s concept of the debt state is once again helpful in exploring the consequences of growing inequities in ownership of the public debt. In Buying Time, Streeck argues that the emergence and consolidation of the debt state has had dire consequences for democratic representation in advanced capitalist countries. Specifically, he asserts that under the debt state governments have come to prioritize the interests of owners of the public debt, the Marktvolk, over the general citizenry, or Staatsvolk.

My research illustrates the ubiquity of the Marktvolk within US policymaking. As concentration in ownership of the public debt increases, Federal Government documents begin to refer much more frequently to the interests of the Marktvolk. In the post-war period, when concentration in ownership of the public debt was low, references to the terms associated with the Marktvolk (like international, investors, interest rates, confidence), were only 75 percent as frequent as those associated with the Staatsvolk (like national, public opinion, citizens, loyalty). Yet during the global financial crisis, when ownership concentration was high, references to the terms associated with the Marktvolk were twice as frequent as those associated with the Staatsvolk.

Concentrated ownership does not necessarily give owners of the public debt direct power over the political process. But it is clear that there has been a transformation in policy in recent years; one that provides an ideological climate that privileges the interests of the bondholding class. Inequality in ownership of the public debt and inequality in representation within government policy are really two sides of the same coin. In this sense, the debt state not only reinforces wealth and income inequality, but it also contributes to the broader erosion of democracy.

What Should (and Should Not) Be Done

Inequality has come to permeate all facets of contemporary capitalism, and so its pervasiveness in the public finances should come as no surprise. What we need to consider is the possible political measures that might be implemented to counteract growing inequities in ownership of the public debt. But before discussing political solutions, a word of caution is in place.

The problem I highlight in the book is not a large public debt. As Abba Lerner first demonstrated in the 1940s, the outstanding level of public indebtedness is inconsequential so long as it is being accumulated as part of a macroeconomic strategy to achieve non-inflationary full employment. In fact, for a monetarily sovereign entity like the US Federal Government, which issues debt in a currency it fully controls, bankruptcy is never really an issue because the Federal Reserve can purchase government bonds when the private sector does not want them. The existence of a powerful bondholding class should provide no solace for “deficit hawks” eager to find evidence to support their fear mongering about the supposed unsustainability of the public debt.

The real problem, then, is a large unequally distributed public debt. This distinction is absolutely crucial. From an emancipatory point of view, the point is not to try to eliminate or even reduce the public debt, but to find ways to tackle the inequality that underpins the public finances. As mentioned earlier, the emergence and consolidation of the debt state was driven primarily by tax stagnation and declining tax progressivity. The debt state, in other words, has come into being because the Federal Government has come to rely on borrowing from the bondholding class instead of taxing it. Restoring progressivity to the federal tax system, by increasing tax rates on wealthy households and large corporations, would therefore go a long way in addressing the growing inequalities in ownership of the public debt and in the ownership of wealth and income more generally.

The real problem, then, is a large unequally distributed public debt. This distinction is absolutely crucial. From an emancipatory point of view, the point is not to try to eliminate or even reduce the public debt, but to find ways to tackle the inequality that underpins the public finances. As mentioned earlier, the emergence and consolidation of the debt state was driven primarily by tax stagnation and declining tax progressivity. The debt state, in other words, has come into being because the Federal Government has come to rely on borrowing from the bondholding class instead of taxing it. Restoring progressivity to the federal tax system, by increasing tax rates on wealthy households and large corporations, would therefore go a long way in addressing the growing inequalities in ownership of the public debt and in the ownership of wealth and income more generally.

Of course measures to make the federal tax system more progressive would encounter stiff political resistance from powerful groups, and would have little impact unless combined with global coordination to minimize tax competition and evasion. And to deal seriously with the problem of inequality, progressive tax reform would need to be combined with substantial increases in social spending, which would be most effectively channeled through a basic income or a federal job guarantee program.

A monetarily sovereign entity like the US Federal Government is not revenue-constrained and does not technically “need” taxes to finance its expenditures. Yet, in a world of deregulation and global capital flows, and with a legal system ineffective in punishing corporate malfeasance, taxation remains one of the few coercive tools that governments possess to influence the behavior of dominant elites. Thus carefully designed measures to bolster the progressivity of the federal tax system would not only help to tackle inequality; most importantly, it would also help to restore democratic control over a bondholding class that has seen its power grow inordinately under the debt state.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/sandy-hager-public-debt-bondholding-class/

Next Magazine article

The 1 Percent Under Siege?

- Brooke Harrington

- September 21, 2016

The Contradictions of Finance

- Richard D. Wolff

- September 21, 2016