Privatizing War

Social movements ought to place private military contractors at the center of a broader critique of authoritarian neoliberalism and America’s permanent war economy.

The New Merchants of Death

- Issue #4

- Author

Photo: NEstudio / Shutterstock

In August 2016, the Pentagon announced that Six3 Intelligence Solutions, a private intelligence company recently acquired by California Analysis Center Incorporated (CACI), which was implicated in the Abu Ghraib scandal, had won a $10 million no-bid army contract to provide intelligence analysis services in Germany, Italy and Syria. They were to work alongside the roughly three hundred US troops fighting against the so-called Islamic State and to depose Russian-backed Syrian leader Bashir al-Assad.

Later, a correction was issued stating that rather than in Syria, the services would be performed in Kosovo instead. CACI has since denied working in Syria.

Hiring a company with as checkered a record as CACI is bound to ignite a backlash against US interference within Syria, and may empower the very forces the US is fighting. The logic underlying the use of private military contractors (PMCs), however, and American foreign policy in the Middle East more broadly, is not a rational one. It is shaped by a political structure beholden to corporate interests who see opportunity in political instability and endless war. CACI’s executive board includes a former CIA Deputy Director and head of its clandestine services after 9/11, a Lockheed executive, and a commander of army training doctrine and command. The company spends over $200,000 annually on lobbying, giving $180,634 in campaign contributions this past election cycle, 77 percent to Republicans, according to OpenSecrets.org, and $162,021 in 2012 (85% to Republicans).

CACI embodies two trends that have gravely hindered democratic political development in the United States over the last generation: an incestuous relationship between military contractors and government officials who end up serving on the executive boards of companies they dole out lucrative contracts to; and the ability of the same companies to finance political campaigns, which curries them favor alongside their lobbying efforts. These tendencies have helped to entrench a system of military-Keynesianism and resulted in an irrational foreign policy that fuels the global political instability that politically connected companies profit from.

Historical Roots and Political Utility

Mercenaries have long been part of American war making, employed particularly to carry out covert operations the public may not have been keen to support. During the Cold War, General Clare Chennault set up a private airline, Civil Air Transport (CAT), to ferry supplies to proxy armies fighting on the front-lines against communism, and companies like DynCorp International and Vinnell Corporation, which later came to play a prominent role in the Global War on Terror, built military bases, performed combat support roles and helped to run black operations.

The Vietnam War was a turning point in modern American history when the consensus in favor of military intervention began to wane. As a result of pressure by a sizeable antiwar movement, the US government was forced to abolish the draft. Policy planners in Washington and the interests associated with the so-called military industrial complex, however, were bent on sustaining US military hegemony. They championed high-tech weapons systems including remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs, or drones) as a substitute for boots on the ground, and pushed for the subcontracting of counterinsurgency to strategic allies. At a time when corporate power was becoming more entrenched, private military contractors were greatly valued as a means of distancing military intervention from the public and keeping a light American military footprint to prevent a reawakening of the antiwar movement.

The Vietnam War was a turning point in modern American history when the consensus in favor of military intervention began to wane. As a result of pressure by a sizeable antiwar movement, the US government was forced to abolish the draft. Policy planners in Washington and the interests associated with the so-called military industrial complex, however, were bent on sustaining US military hegemony. They championed high-tech weapons systems including remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs, or drones) as a substitute for boots on the ground, and pushed for the subcontracting of counterinsurgency to strategic allies. At a time when corporate power was becoming more entrenched, private military contractors were greatly valued as a means of distancing military intervention from the public and keeping a light American military footprint to prevent a reawakening of the antiwar movement.

A particularly controversial aspect of US foreign policy in the 1970s was support for the Saudi Royal family, which provided the US access to cheap oil at a time when the OPEC embargo had raised global prices, and demanded payment for all its oil sales in American dollars. In return, the Nixon administration and its successors agreed to provide for internal security by arming and training the National Guard. They hired Vinnell Corporation, which in 1979 provided the tactical support needed by the Saudi Princes to put down a leftist rebellion and recapture the Grand Mosque at Mecca.

In 1981, Executive Order 12333 gave US intelligence agencies the right to enter into contracts with private companies for authorized intelligence purposes, which need not be disclosed. This provided a basis for some of the arms smuggling operations using private airlines in the Contra war in Nicaragua. The 1990s was a key growth period for the private military industry because of factors that included the waning of public support for military intervention following the end of the Cold War, a proliferation of ethnic conflicts that the United Nations and United States were seemingly incapable of dealing with, and the growth of corporate lobbying power in an age of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism in theory, as political economist David Harvey has noted, proposed that human wellbeing could best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong property rights, free markets and free trade. The main goal of the state in this system is secure property rights and the proper functioning of markets. In practice, however, neoliberalism has transferred power from public to private hands, hence eroding democratic standards and resulting in the entrenchment of corporate power. It has intensified inequality and suppressed labor rights and been accompanied by systematic state repression, epitomized in the United States by the intensification of the War on Drugs and the mass incarceration state.

The privatization of law enforcement and military functions is an important manifestation of neoliberalism, which embodies how, as Ian Bruff puts it in his introductory essay, “the intertwining of commercial and security forms of power leads to considerably greater possibilities for control of populations.” The reason centers in part on a lack of public transparency and capacity for proper regulations and oversight of private corporations and their use of coercive force and social control technologies as they become one with the government. There is also new opportunity to manipulate public opinion to further private interest centered on maximizing profit at the expense of human consideration.

States like the US have traditionally deployed their repressive powers against political undesirables who threaten elite privilege either at home or abroad. However, these efforts have at times been constrained by international and domestic legal considerations and domestic constituencies valuing civil liberties, peace and human rights. As governments gradually became more beholden to private interests in the neoliberal era, such constraints have increasingly been lifted as citizens are asked to bear less sacrifice, and have less of a stake and even knowledge of what their government is doing abroad. Citizens at the same time may be conditioned to care only about the individual accumulation of wealth, leading to the further erosion of civic consciousness and prospects for engagement with social movements.

The Global War on Terror as a Super Bowl for PMCS

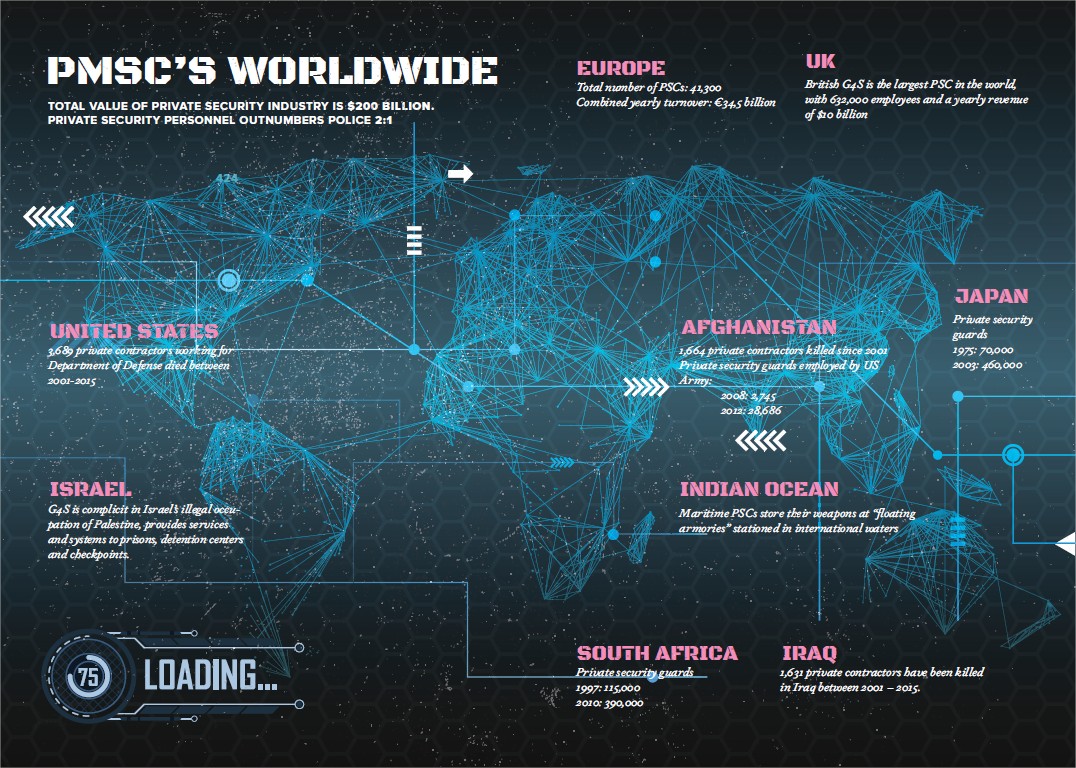

From 1994 to 2002, the Pentagon signed more than 3,000 contracts with US-based firms valued at $300 billion. These totals increased following the declaration of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), which was considered the “Super Bowl” for PMCs that had made over $100 billion in Iraq alone by 2008.

Upon his appointment as defense secretary by President George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld had set about reducing the wasteful Pentagon bureaucracy and revolutionizing the US armed forces by moving towards a lighter, more flexible fighting machine and harnessing private sector power on multiple fronts. He wrote in Foreign Affairs that “we must promote a more entrepreneurial approach: one that encourages people to be proactive, not reactive, and to behave less like bureaucrats and more like venture capitalists.”

As resistance to US occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq intensified, the military became overstretched and, in the absence of a draft, began lowering its recruitment standards to include ex-criminals and even neo-Nazis. A number of soldiers refused redeployment for second and third tours. Private contractors filled an important void, performing key military functions such as protecting diplomats, transporting supplies, training police and army personnel, guarding checkpoints and other strategic facilities including oil installations, providing intelligence, helping to rescue wounded personnel, dismantling IEDs, carrying out interrogation and even loading bombs onto CIA drones. A British mercenary pointed out that military commanders “do not like us, [but] tolerate us as a necessary evil because they know that if it wasn’t for us, they would need another 25,000 to 50,000 troops on the ground here.” And politically, after Vietnam, this was impossible to arrange.

At various points in the 15-year war in Afghanistan, the number of military contractors actually outnumbered US troops. As of April 2016, there were at least 30,000 private contractors still there. There are also approximately 7,100 contractors currently supporting US government operations in Iraq, doing jobs from washing laundry and providing security on bases to training police and military officers to advising the Kurdish regional government in Erbil and the Iraqi government in Baghdad. Some of the money comes from a reported $52 billion CIA black budget disclosed in 2013 by Edward Snowden.

At various points in the 15-year war in Afghanistan, the number of military contractors actually outnumbered US troops.

Shawn McFate, author of The Modern Mercenary: Private Armies and What They Mean for World Order, told the Daily Beast that “contractors encourage mission creep because they allow the administration to put more people on the ground than they report to the American people.” They also enable executive secrecy by performing covert operations the American public may not support, like aspects of the drone war they are involved with and the smuggling of arms to the rebels in Syria purchased from al Qaeda militia leaders in Libya.

Representatives from PMCs at the same time often play an instrumental role in manipulating public opinion by selling wars they profit off. Since 2001, former four-star General Barry McCaffrey has been a military analyst at NBC News where he has often supported American military interventions. McCaffrey also happens to serve on the Board of Directors of DynCorp, which received a billion dollar contract for training the Afghan and Iraqi national police.

Problems with Private Military Contractors

Proponents of PMCs claim that they can offset the weakness of state security forces in impoverished countries and will operate in areas like West Africa to halt genocide or other human rights atrocities that national armies will not venture into. They also claim that PMCs provide more efficient security services, epitomized in Blackwater founder Erik Prince’s boast about revolutionizing the industry like FedEx had the mail service.

Congressional investigations, however, uncovered numerous cases of fraud and dangerously poor construction by PMCs in Afghanistan and Iraq, resulting in the deaths of at least eighteen troops, including a Green Beret who was electrocuted in a shower installed by Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR), whose war contracts totaled $39.5 billion. Over 25,000 soldiers got sick after KBR did not properly chlorinate the water at Camp Ramadi owing to cost-cutting measures and because they burned waste in environmentally unsound ways with little oversight. A police-training academy built by DynCorp was so poorly constructed that urine and feces fell on its students. These occurrences show the delusions of neoliberals in their belief in the inviolability of private business, extending to the realm of security.

A major danger associated with the privatization of security is that security becomes the domain of only the wealthy — that is, for those who can pay for it. PMCs operating in Iraq, for example, were given lucrative contracts to guard Iraq’s ravaged oil fields, which were opened up to foreign multinationals, though the Iraqi police force was underfunded and unable to protect the public from sectarian violence and insurgents. Parallels can be seen in other places like Latin America, where PMCs guard oil pipelines or mining companies when public security is generally poor.

A lack of government oversight and transparency magnifies the capacity for contractor abuse. DynCorp employees were implicated in illegal arms smuggling and involvement in the child-sex slave trade in Bosnia and a host of abuses in Afghanistan including drunken disorderly conduct, torture and hiring teenage “dancing boys.” In 2007, Blackwater operatives in Nisour Square infamously killed 17 unarmed civilians, including women and children, and wounded at least 24 in a shooting rampage.

While atrocities in war are frequent, the propensity was magnified by the fact that PMCs had legal immunity and were not subject to either Iraqi law or the Uniform Military Code of Justice, nor the Geneva Conventions. Many companies also did not follow rigorous recruitment methods or training standards and allowed employees to take steroids. In addition, there was a culture of militarized masculinity that appears greater than that of the military itself. One Triple Canopy employee told a reporter that: “It was like romanticizing the idea of killing to the point where dudes want to do it… Does that mean you’re not a real man unless you’ve dropped a guy?” While such comment could be made by someone in the army, the possibility of court martial there can help constrain excessive violence.

Manipulation of Intelligence and Permanent Warfare

The most damaging aspect of PMCs is undoubtedly the possibility for manipulating intelligence. In Afghanistan, the army contracted with American International Security Corps, headed by former CIA agent Duane “Dewey” Clarridge, convicted of lying to Congress about Iran Contra, who investigated Hamid Karzai’s alleged addiction to heroin and the-drug related corruption of his brother Ahmed Wali for the purpose of keeping them more pliable or to plot a coup. Clarridge also provided reports that were in some cases dubious to Fox News commentators, including his old comrade Oliver North, with the goal of supporting a more aggressive military policy. His actions epitomize the danger of privatizing intelligence, in that private citizens can take advantage of the chaos of the war zone to advance their own agendas or feed misinformation to the military or public.

On the eve of the Iraq War, Science Application International Corporation (SAIC), which earned the moniker “NSA-West” for spearheading a surveillance program called Trailblazer that involved the mining of personal records, ran a program that fed disinformation to the foreign press and set up a media service in Iraq, which served as a mouthpiece of the Pentagon. SAIC’s chief operations officer from 1993-2006, Duane Andrews, was a protégé of Dick Cheney who provided fake satellite photos showing a build-up of Iraqi troops on the Saudi Arabian border as a staff member on the House Intelligence Committee in 1991. Another board member, General Wayne Downing, was a close associate of Ahmad Chalabi, an Iraqi exile whom the US promoted as Iraq’s next leader and who proselytized hard on television for an invasion of Iraq. The FBI at one point even suspected an SAIC employee for the 2001 anthrax mailings, which did so much to create a climate of fear enabling support for the War on Terror and passage of the USA Patriot Act, a bonanza for SAIC, which recorded net profits of over $8 billion per year by 2006.

Much like with Iraq and Afghanistan, the private military industry was salivating at the prospect of massive reconstruction contracts following the 2011 US-NATO war on Libya. The head of the security contractor network based out of Alexandria, Virginia wrote on his blog about the new post-Qaddafi context in which there was an “uptick of activity as foreign oil companies scramble[d] to get back into Libya [after Qaddafi had nationalized considerable portion of the industry]. This means an increase in demand for risk assessment and security related services… Keep an eye on who is winning the contracts. Follow the money and find your next job.”

British-based G4S, the world’s third-largest private employer, which provides surveillance equipment to checkpoints and prisons in the Israeli-occupied territory, was one of the bigger winners along with Aegis Security headed by the legendary soldier of fortune Tim Spicer and Blue Mountain Group — another British firm hired to guard the US embassy in Benghazi. Equipped mainly with flashlights and batons instead of guns, the Blue Mountain Guards were ill-equipped to deal with the September 11, 2012 insurgent attack that led to the death of US Ambassador Christopher Stevens.

British-based G4S, the world’s third-largest private employer, which provides surveillance equipment to checkpoints and prisons in the Israeli-occupied territory, was one of the bigger winners along with Aegis Security headed by the legendary soldier of fortune Tim Spicer and Blue Mountain Group — another British firm hired to guard the US embassy in Benghazi. Equipped mainly with flashlights and batons instead of guns, the Blue Mountain Guards were ill-equipped to deal with the September 11, 2012 insurgent attack that led to the death of US Ambassador Christopher Stevens.

Meanwhile, an FBI probe into Hillary Clinton’s emails uncovered that one of Clinton’s top aides, Sidney Blumenthal, a longtime family fixer and $10,000 per month employee of the Clinton foundation, used his direct access to the then Secretary of State to promote his business interests in Libya. Prior to and during the war, Blumenthal would frequently email Clinton with intelligence information derived from the off-the-books intelligence spy networks that may have encouraged Clinton’s strong backing for an expanded US military role in Libya. Blumenthal at one point enthused to Clinton about opportunities for private security firms that could “put America in a central role without being direct battle combatants.”

A key firm wanting to get in on the action was Osprey Global Solutions, which Blumenthal had a financial stake in. According to Tyler Drumheller, an ex-CIA agent and Osprey executive, Blumenthal was to receive a finder’s fee for helping to secure State Department approval and arrange a contract for training security forces and building a floating hospital and schools in the war-torn country. At one point, Blumenthal even proposed bringing in, as an adviser to the fledgling post-Qaddafi government, a man named Najib Obeida, whom he hoped would finance Osprey’s operations in Libya.

Though the deal eventually fell through, the conflict of interest with Blumenthal and Osprey epitomizes how the lure of private contracts and monetary gain could help skew intelligence and push the United States or any other country towards war. Policymakers like Clinton themselves saw great utility in using private contractors to feed them information that would rationalize a hawkish position and help open up opportunities for foreign investors who would line their political coffers come election season.

PMCs and the Corruption of American Democracy

During his 2016 Democratic Party presidential campaign, Bernie Sanders condemned the overweening influence of money on politics and the corruption bred by corporate power. However, Sanders focused most of his critique on the big pharmaceutical, fossil fuel and investment banking firms, only rarely discussing the so-called military-industrial complex and never the private military industry. But more than anything else, this $200 billion industry epitomizes the corruption of the two-party system in the era of Citizen’s United. It is also key to the US global strategy of maintaining a worldwide network of overseas military bases and waging endless wars for access to natural resources, which most of the public would not want to risk its life fighting in.

Rather than protecting open markets as in neoliberal ideology, the government in the United States today functions to enrich its corporate benefactors who profit off the chaos bred by endless war. Alongside major defense contractors, PMCs spend huge sums of money annually in lobbying, and are staffed by former and future government employees who consider public service as a means to obtaining private wealth. They donate huge sums to Super PACs, dividing between Democrats and Republicans. Since 2012, DynCorp International, which received the most lucrative contracts for training the Afghan and Iraqi police, has spent over $800,000 on House and Senate races, for example. CACI has spent well over $200,000 and has been amply rewarded, recording net profits of $350 million in 2005 and $3.7 billion in 2012 when it was hired to run counter-narcotic operations in Afghanistan.

Rather than protecting open markets as in neoliberal ideology, the government in the United States today functions to enrich its corporate benefactors who profit off the chaos bred by endless war.

In a 2012 essay entitled “America’s Permanent War Economy,” the late Columbia University economist Seymour Melman emphasizes the social and human costs of militarism in US society for the domestic population, suggesting it resulted in neglect for public education, public health and infrastructural development programs and skewed the national economy by creating artificial debt and depleting the manufacturing sector by channeling investment away from productive industry.

The increasing stature of PMCs in the last generation has tipped the balance even further away from a more sensible distribution of national wealth, while exacerbating economic problems and contributing to national decline. Imperialist powers like the United States have always found motives to intervene militarily in sovereign countries or support covert missions, to be sure — however, civil strife in places like Syria, Afghanistan and Libya today is increasingly considered as a business opportunity for PMCs, whose representatives can skew intelligence or trumpet intervention on television while financing political candidates who will do their bidding. The consequence is a state of permanent, endless war that is fueling tremendous blowback and instability around the world, and that could lead to national self-destruction.

What Can Be Done

Existing social movements ought to include PMCs at the center of a broader critique of authoritarian neoliberalism and capitalism more generally. In the United States, a push for Congressional investigations along the lines of the 1930s Nye commission on corporate war profiteers (“merchants of death,” as they were then called) and 1970s Church committee hearings on CIA abuses would be a welcome start in raising public awareness about the threat to democracy bred by the privatization of military and intelligence functions. They could in turn lead to legislation that properly regulates or even outlaws PMCs, making war far less likely in turn by removing the profit motive.

A 1989 United Nations treaty prohibits the recruitment, training, use and financing of mercenaries or combatants motivated to take part in hostilities by private gain, though the United States never signed and PMCs have claimed exclusion on the grounds that they play a combat support role. The 2008 Montreux document supported by 46 nation states and the European Union describes international humanitarian law and human rights law as it applies to the activities of PMCs during armed conflict and provided recommendations for better oversight and means of holding them accountable for criminal acts. The document, however, is non-binding and according to analysts “lacks legal teeth.”

It will take large-scale pressure from below to push the United States and EU countries to give Montreux some legal teeth and get them to sign onto the existing UN treaty. This is an urgent task which should go hand in hand with the promotion of alternatives to neoliberal capitalism and the corporatized world order whose adverse consequences PMCs embody.

Correction 12/02/’17: The essay previously suggested that CACI donated money to Super PACs, but instead it donated the money directly to political parties/campaigns.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/the-new-merchants-of-death/

Next Magazine article

The Dog-Whistle Racism of the Neoliberal State

- Adam Elliot-Cooper

- December 18, 2016

The Drone Assassination Assault on Democracy

- Laurie Calhoun

- December 18, 2016