Social Unionism

As informality becomes a major feature of the global economy, street syndicalism may be the key to putting human dignity over property rights.

The Street Syndicate: Re-organizing Informal Work

- Issue #2

- Author

Christopher Columbus towers over Barcelona, pointing outward, far beyond the harbor. Carved in stone beneath him, an indigenous man kneels before a priest, head down, eyes averting the holy man’s gaze. Built in 1888 for Spain’s first International World’s Fair, this monument to colonialism stands where the port meets the Ramblas—the tree-lined mall Orwell described as the Catalan city’s “central artery”. There, it commemorates the bloody events that inaugurated Western dominance over the global economy. And today, it is a flashpoint in the struggle between life, property and the Sovereign.

This is among the first places tourists see when they step off of luxury liners and into Europe’s cruise ship capital. In every direction, the path is framed by commerce. Boisterous salsa music shuffles sweetly over the din as street musicians, vendors and artisans compete for the visitors’ attention with over-priced restaurants, tacky cocktail bars, hotels and corporate shopping centers. But every so often, the party is violently broken down. In a coordinated effort to expel them from the city’s streets, police forces from three separate authorities—local, regional and port—charge at dark-skinned street vendors, swatting at their backs and limbs with telescopic steel batons. It’s an unsettling sight, but an increasingly common one in a city that has come to symbolize the European left’s hopes for a working model of emancipation.

Informal work has never fit neatly within leftist categories. While the governing left tends to view it as a space for regulation, in more anarchistic circles it is often treated with suspicion as a field dominated by capitalist values. For mainstream organized labor, informal work is just one more form of exploitation that happens to affect women, migrants and other vulnerable groups more than others. The International Labor Organization (ILO), for instance, defines its characteristic features as a lack of protection against non-payment of wages, compulsory overtime or extra shifts, lay-offs without notice or compensation, unsafe working conditions and an absence of social benefits including pensions, sick pay and health insurance.

Of course, none of this is false. But the characteristics outlined by the ILO hinge on expectations defined by the social rights particular to Western welfare states. In this sense, they depart from a very specific idea of work constructed within a very specific set of power relations—namely, those depicted in the Monument to Columbus. That African and Asian informal workers are routinely pursued next to scenes from what Marx called “the chief moments of primitive accumulation” harbors a poetic truth. To unpack that image is to unveil one of the critical antagonisms at the heart of world trade.

Codifying Informality

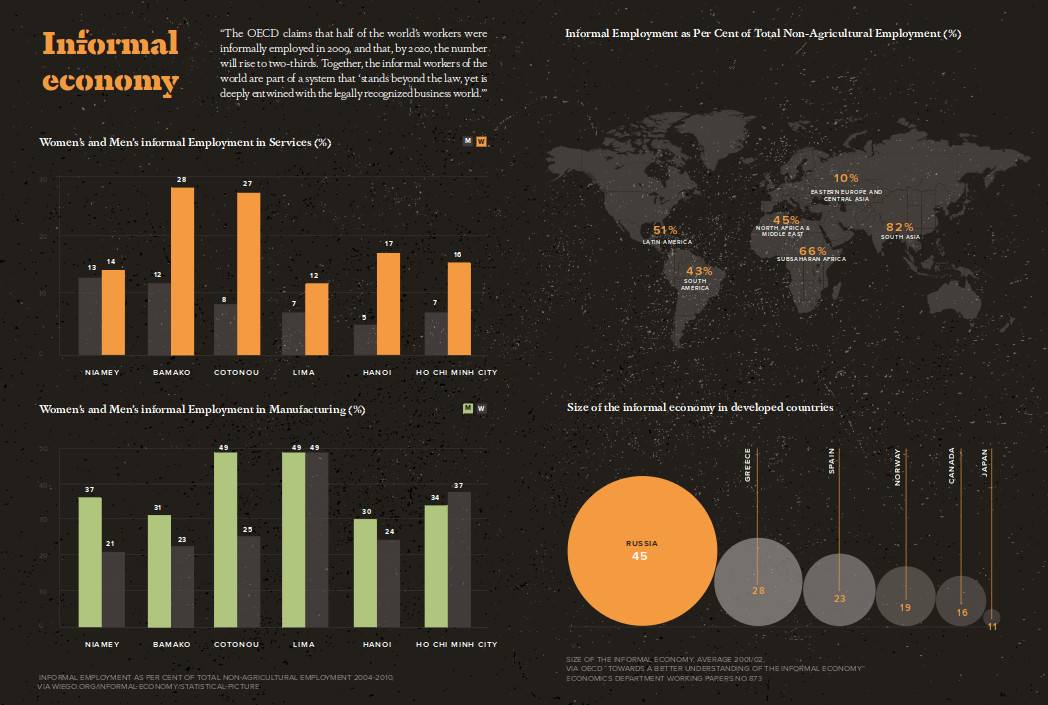

The concept of “the informal economy” was coined by the anthropologist Keith Hart in the 1970s as he was studying low-income work in Accra, Ghana. It’s an odd term when you consider that, according to the ILO, between half and three-quarters of the non-agricultural work being done in developing countries falls into the category. In fact, the OECD claims that half of the world’s workers were informally employed in 2009, and that, by 2020, the number will rise to two-thirds. So by labeling it as “informal”, it appears we are depicting most of the work being done in the world as an anomaly, peripheral to the global “formal” economy.

But this was not Hart’s intention when he first applied the term. Departing from Marx’s notion of the “reserve army of the unemployed”, he was more interested in knowing whether the “surplus population” of low-income workers in the urban Third World were a “passively exploited majority” or if their informal economic activities possessed “an autonomous capacity for generating incomes”. At the time, he concluded that both were true, to a certain extent, and that there was some potential there for economic development.

The ILO were particularly enthusiastic about his findings. After seeing Hart present his work at a conference in 1971, and before he could even publish his work in an academic journal, they sent a large employment mission to Kenya. There, they examined the potential for converting the country’s traditional economy—which they began to refer to as “the informal sector”—into something more in line with the “formal economy” of Western welfare states. This approach continues to this day, and the formalization of informal work has gone on to become an important part of the ILO’s Decent Work Agenda.

The ILO were particularly enthusiastic about his findings. After seeing Hart present his work at a conference in 1971, and before he could even publish his work in an academic journal, they sent a large employment mission to Kenya. There, they examined the potential for converting the country’s traditional economy—which they began to refer to as “the informal sector”—into something more in line with the “formal economy” of Western welfare states. This approach continues to this day, and the formalization of informal work has gone on to become an important part of the ILO’s Decent Work Agenda.

Meanwhile, Hart’s position has evolved somewhat. In recent years, he has described the informal economy as the antithesis of the national-capitalism that dominates world trade. He also claims that it has become “a universal feature of the modern economy” as a result of the deterioration of employment conditions in rich countries, which began in the 1980s under Thatcher and Reagan and was exacerbated in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Sociologist Saskia Sassen explores this further in her own research, attributing the expansion of informal work in advanced capitalist countries to two main processes. The first is rising inequality and the resulting changes in the consumption habits of the rich and poor. The second is the inability of most workers to compete for the basic resources needed to operate in urban contexts, since leading firms tend to bid up their prices. This is particularly notable in the price of commercial space.

Yet, raising the costs of participating in commerce or national labor markets is not solely the domain of private enterprise. The state plays a major role in reproducing national-capitalist class relations through the selective inclusion or outright criminalization of certain types of work and certain types of people. This is especially clear in the case of undocumented migrants or ex-convicts, minoritized workers who are expelled from the formal economy and warehoused in slums, prisons and detention centers. If neoliberalism is, as sociologist Loïc Wacquant claims, “an articulation of state, market and citizenship that harnesses the first to impose the stamp of the second onto the third,” then it is the tension between unemployment, informality and survival that makes its most repressive institutions so sticky.

Because it encompasses work that lies beyond the halo of legitimacy that enshrines national-capitalist values, informality is often associated with corruption and violence in the Western imagination. This has implications at both the global and local level. In poor countries, the informal economy provides an impetus for colonization via the imposition of Western norms and legality. In rich countries, the very real employment insecurity faced by informal workers is believed by citizens to be a breeding ground for shadowy mafias, and thus a threat to their own security.

The recent implementation of Spain’s draconian Citizen Security Law is a textbook example of how this social dynamic becomes codified into public law. Better known as the Gag Law, the legislation drew considerable attention from the international press and human rights groups due to its assault on the right to protest. Less was written, however, about how it punishes being poor in public by levying heavy fines on informal workers whose livelihoods depend on their access to public space. Coupled with a simultaneous reform of the country’s penal code, the new legislation inaugurated a sea change in policing poverty which cemented the informal sector’s role as the pipeline connecting prisons with the urban periphery.

A System of Mutual Aid?

Almost everything you see in the Besòs neighborhood was built by and for migrant workers. Lying on the outskirts of Barcelona, on the southwestern bank of the Besòs River, it began as a shantytown housing workers who had come from Southern Spain to work on the 1929 International World’s Fair. From then on, its history has been a tug-of-war between the precarious structures of the informal city and the hulking bureaucracy of the metropolis, as successive waves of migrant workers organized into rowdy neighborhood associations to demand the most basic forms of urban infrastructure.

But despite countless bottom-up victories, it remains a poor neighborhood. Today, roughly 30 percent of the population was born abroad, primarily in poor countries, and families earn roughly half the income of the average Barcelona household. This is where many of the Senegalese street vendors who sell bootlegged goods by the harbor live, partly due to the dynamics inherent to international migration and partly due to severe racial discrimination in Barcelona’s housing market. “The moment property owners hear your accent, they just hang up,” Mamadou tells me when I ask if he’s ever experienced racism while looking for a place to live. “Sometimes they’ll just flat-out say it: ‘Nope. No Africans.’”

The house I’m in is small, but well-kept. The image of a smiling Sufi marabout hangs serenely on the wall as the television news mumbles quietly in the background. The sweet, spicy smell of djar drifts in from the kitchen where a fresh pot of café touba is being brewed. Noting that there are only three tiny bedrooms, I ask my host how many people live here. “About six or seven,” he answers. Curious, I ask him where they all sleep. He tells me people generally come and go as they please, but a few stay all the time. That’s why the number he gave me is so high. When I ask him if it doesn’t get crowded with so many people, he nods, “A little. But we’re not going to let another African sleep on the street.”

I ask him if he’s ever thought about pointing people towards social services, since they often provide food and shelter for people who need it, and aren’t finicky about whether one’s immigration documents are in order. “Yeah, I know about social services,” he replies. “They give you a meal ticket and a roof and that’s it. But we don’t need those things.” He notices my surprise and smiles. “Tell me,” Mamadou says. “Have you ever seen a black man sleeping in one of those ATM buildings?” Come to think of it, I haven’t. Or at least, not many. “If you have, they probably weren’t African,” he explains. “Look, we think of things very differently than you. Every African here knows they can go to a friend for a plate of rice or a place to stay for the night. We take care of one another. We don’t go hungry and we don’t sleep in the cold. Not yet, anyway.”

It’s actually not the first time I’ve heard this argument. This exact sentiment is often repeated by the African recyclers that have spent the better part of the last decade living and working in the abandoned warehouses of the de-industrialized Poblenou neighborhood. It is also used in reference to Spanish families, to explain why there is not more social unrest despite the country’s high unemployment. Hearing it again, I can’t help but think of what Kropotkin wrote about the resilience of mutual aid against the onslaught of the centralized state, how “it reappeared and reasserted itself in an infinity of associations which tend to embrace all aspects of life and to take possession of all that is required by man for life.”

Investigative reporter Robert Neuwirth also recognizes this aspect of informal work. In his book Stealth of Nations: The Global Rise of the Informal Economy, he criticizes Hart’s notion of informality for aligning roadside vendors and hawkers with the criminal underground and political corruption. Instead, he refers to the activities carried out by street vendors, street artists or informal recyclers as the result of self-organization, group solidarity and collective intelligence, loosely structured around a set of well-worn but unwritten rules.

Together, the informal workers of the world are part of a system that “stands beyond the law, yet is deeply entwined with the legally recognized business world.” To refer to it, Neuwirth imports a slang term from French-speaking Africa and the Caribbean: System D. But in October 2015, Barcelona’s street vendors started using a concept that is substantially more familiar in Spain: el sindicato. The union.

Disobeying Unemployment

Walking up the Ramblas can be a bit like trying to illegally stream a TV show. Immediately, you are overwhelmed by cheap attempts to lure your senses, in a manner that recalls those invasive pop-up ads for gambling sites, porn and online fantasy games. Small flower shops sell vulgar souvenirs, like pussy flowers and dick-shaped peppers. Pushy waiters approach you from sidewalk cafés, menus in hand as they try to convince you to sit down for an oversized beer or sangria and some terrible tapas. On a nearby balcony, a Marilyn Monroe lookalike reenacts the famous subway scene from The Seven Year Itch, drawing your attention to the Erotic Museum of Barcelona.

Today, however, is different. Almost the entire length of the kilometer-long mall is lined by about a hundred street vendors. In an attempt to appease local merchants, they leave a bit of distance between the blankets they display their merchandise on and the space taken up by “formal” businesses. West-African men stand behind knockoff Barça jerseys and D&G handbags, Bangladeshis next to umbrellas covered in shiny earrings. A handful of Senegalese women sell colorful jewelry to tourists, homemade food and cold, sugary hibiscus tea to the vendors. Accompanying each worker is a local with a sign or banner. The most common slogan reads Sobrevivir no es delito. It is not a crime to survive.

The Popular Union of Street Vendors began as an attempt by the vendors to negotiate with local authorities and confront the pervasive rumors and racist stereotypes that are frequently repeated in discussions about their work. But as police pressure has made their jobs increasingly difficult, they’ve teamed up with the Espacio del Inmigrante, a Zapatista-inspired migrants’ rights group, and Tras la Manta, a network of local activists who support their cause, to organize what they are calling “rebel flea markets”.

The logic behind these actions is similar to the civil disobedience campaign that made the former housing rights activist and Mayor of Barcelona Ada Colau a household name. By accompanying the vendors in their activity, they make police intervention far more costly, both economically and politically. It is, in many ways, a form of social unionism. And what is particularly interesting about the Popular Union’s actions and discourse is how they expand the vocabulary of local movements to encompass a broader dynamic of globalized antagonism against the Western habit of putting property rights over human dignity.

The logic behind these actions is similar to the civil disobedience campaign that made the former housing rights activist and Mayor of Barcelona Ada Colau a household name. By accompanying the vendors in their activity, they make police intervention far more costly, both economically and politically. It is, in many ways, a form of social unionism. And what is particularly interesting about the Popular Union’s actions and discourse is how they expand the vocabulary of local movements to encompass a broader dynamic of globalized antagonism against the Western habit of putting property rights over human dignity.

“They say our work is illegal,” cries union spokesperson Lamine Sarr over the loudspeaker. “We consider it disobedience. We are disobeying hunger. We are disobeying unemployment. We are disobeying borders. The very idea that some people can go and work wherever they want while others can’t. The very idea that some people have human rights while others don’t.”

The Popular Union is a major nuisance for Ada Colau’s city government. The moment her left-wing municipal platform Barcelona En Comú took office, the mainstream press brought local business leaders’ calls for social cleansing out from their usual place in the Letters to the Editors section and put them on the cover. Meanwhile, local police unions began putting out a constant stream of press releases criticizing city hall for not applying a firm hand to what they consider a threat to public safety.

It’s not the first time this has happened. Every time the left has come into power here, the mainstream press, security forces and the local business community have used informal workers as a pressure point to destabilize the government. When a coalition between the Socialist Party, the Catalan Greens and the Republican Left took office in 2004, for instance, they were bullied by the press, police and merchants into passing the civic bylaws that eventually became the model for Spain’s Gag Law.

It also happened when the left won Barcelona’s municipal elections in 1931, forcing King Alfonso XIII out and inaugurating the Second Spanish Republic. As historian Chris Ealham describes in Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter-revolution in Barcelona, 1898-1937, the local press frequently published stories in which prominent local business associations called on the city to eradicate street trade using “all means necessary”, threatening that they “were ready to take the law into their own hands if ‘unlicensed traders’ remained on the street.”

The Colau government has responded to this conflict by shifting blame upwards while working to please all sides. They began by recognizing the Popular Union and trying to sit them down at a table with local police, NGOs and local business leaders to discuss the situation. Unsurprisingly, this was sabotaged by the police and the business community, who refused to recognize the union. Then they began to emphasize the social integration of the mostly undocumented street vendors through a job-training program run by the city’s social services. But because the penal code considers their work a criminal activity, it is all but impossible for the street vendors to receive favorable reviews when they apply for residency, making their participation in the formal labor market all the more difficult.

Meanwhile, rather than confronting higher levels of public administration like the Catalan government or the Spanish state, the city has opted for a legalistic defense of intellectual and industrial property, collaborating with the Catalan Mossos d’Esquadra to crack down on the informal economy generally and the street vendors specifically. This can only increase the number of street vendors with criminal records, further complicating any attempt to successfully regularize their documentation status or participate in the formal labor market. And where it does succeed in halting the street vendors’ activity, it effectively dismantles the material infrastructure of their system of mutual aid, making it impossible for them to pay rent, and pushing them closer to either living on the street or working in the criminal underground.

Street Syndicalism or the Uber Mafia?

At the base of the Columbus monument’s pedestal, there are four statues of Catalan historical figures who are thought to have made his voyages possible. One is Father Bernat de Boïl, the priest mentioned at the beginning of this article. The other three are the diplomat Jaume Ferrer de Blanes, royal finance minister Luis de Santángel, and Captain Pere Margarit, who is also depicted next to a submitting indigenous man. Together, they represent the four types of power—moral, political, financial and military—that sustain the legal order of the Sovereign in the Western-dominated era of world trade.

If the colonial project consists in submitting all other forms of value and legitimacy to the formalities of that legal order, informality is both what lies beyond the Sovereign’s reach and what grows in the cracks of its institutional architecture. In a context where the multiplication of labor and the emergence of new forms of employment are testing the limits of that architecture, informality can either be appropriated to fortify national-capitalism or organized to dismantle it.

The emergence of the so-called “sharing economy” is an example of how informality can be appropriated to fortify national-capitalism. After the global financial crisis left millions of younger workers unemployed, many of those workers responded to their lack of access to commercial space by selling their work on the internet. The result? Companies like Uber and Amazon Mechanical Turk privatized the System D-style networking that allows these workers to earn a living, and then challenged governments to adapt their legal structures to their “no-benefits” employment scheme.

The Popular Union, on the other hand, overcame their lack of access to commercial space by occupying public space. There, through the sale of bootlegged goods, they re-appropriate a portion of the market value associated with large clothing brands and feed it into a system of mutual support that provides food and shelter for people who are denied those by the legal order. Of course, this work has been criminalized. But at the end of the day, it is the Popular Union’s syndicalism that seems more like “sharing” and Uber that seems more like a mafia.

The question of how informality is organized is not going away anytime soon. Long-term unemployment is becoming an increasingly dominant feature of the global economy and systems are being forced to adapt to one model or the other. If we are to confront a regime that has been built around private interests and property, the street syndicalism of the Popular Union is a vital example of how to put human dignity over property rights.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/the-street-syndicate-re-organizing-informal-work/

Next Magazine article

Will Robots Take Your Job?

- Nick Srnicek, Alex Williams

- June 25, 2016

Workers’ Control in the Crisis of Capitalism

- Dario Azzellini

- June 25, 2016