A Shared Horizon

As the sites of a shared lived experience, cities offer a unique opportunity to develop new political subjectivities that move beyond nationality and citizenship.

Urban Sanctuary: The Promise of Solidarity Cities

- Issue #6

- Author

Sanctuary cities, solidarity cities, fearless cities, rebel cities — in recent years, we have witnessed the emergence of a new cycle of struggles around the theme of urban space in various parts of the Global North. For those in the United States, it is almost impossible not to have heard of sanctuary cities (where municipal authorities refuse full compliance with national immigration laws to offer limited shelter and public services to undocumented migrants and refugees), or at least of Donald Trump’s threats to end federal funding for them. In Canada, the cities of London and Montreal recently declared themselves sanctuary cities as a direct reaction to Trump’s xenophobic anti-immigration discourse.

The idea of the sanctuary city also extends to Europe, where it is attracting increasing attention from journalists and researchers alike. These developments clearly show how the notion of the sanctuary city has gained political salience over the last years, constituting a growing threat to the neoliberal and conservative order of things across the globe. It is this radical potential of sanctuary cities that motivated us to adopt the concept here in Berlin, trying to improve urban living conditions while simultaneously working on the further development of the political concept itself. The notion of the sanctuary city itself is flexible, depending on the needs and orientations of the communities pushing for it, which sometimes leaves it vulnerable to cooptation or sheer meaninglessness. But aside from the legitimate critiques and questions that can be raised, the potential of sanctuary cities to offer new organizational structures is promising enough to warrant a closer look.

Protection, Service and Hospitality

If there is one common denominator behind the different municipalities that claim the mantle of sanctuary city, it is to make urban spaces safely accessible, independent of formal residency status. Beyond that, the shared attributes are very limited. In North America, for instance, some cities focus on ending the collaboration between federal deportation agencies and the local police. Others focus on municipal policies that allow “access without fear,” so that undocumented migrants can access medical, educational and other social services without having to fear that the respective service providers will inform deportation agencies. Others still just seem to claim the title to signal that the city ambiguously aims for a non-racist living environment.

These differences are mirrored in the identities and strategies of the actors fighting to make their city a sanctuary city. In some places, the main protagonists are strong grassroots movements, pushing the city’s government to implement protective legislations. The No One Is Illegal campaign in Toronto is one such example. In other places, the city’s government declares the city a de facto sanctuary city without further legal changes. National City, California is an example of this approach. In others still, grassroots movements fight for a sanctuary city based on informal support structures, with the city’s government actively opposing their efforts. Miami, Florida is currently an example of this type of case.

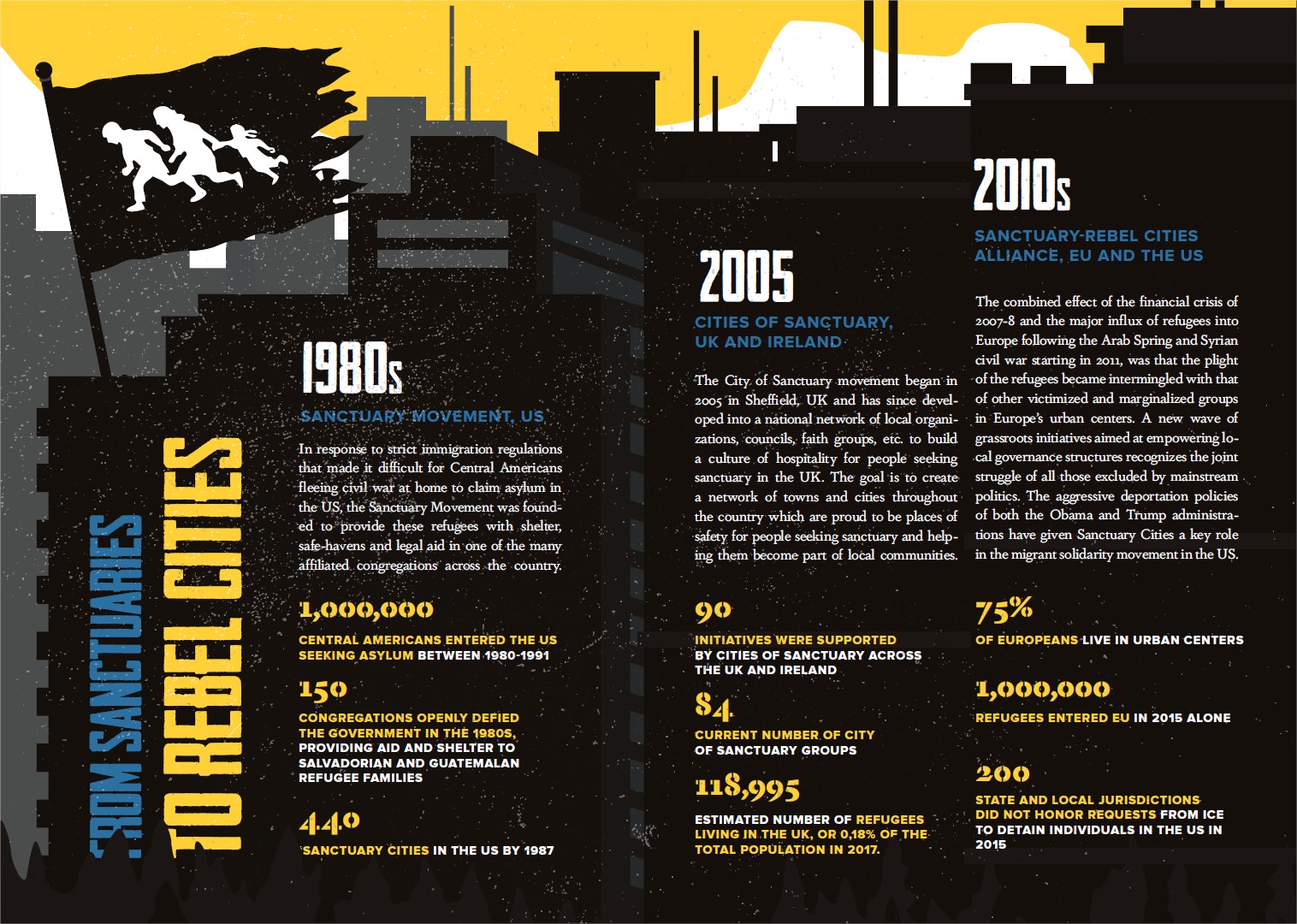

To understand the many differences and similarities, a short overview of the history and context of the concept of the sanctuary city is therefore helpful. The term sanctuary city can be found over many centuries, crossing state lines and religious divides and standing for some kind of protection within the city walls — often protection from oppression or persecution. The modern concept, however, was developed in the US as a reaction to increasingly restrictive migration policies and a rapid retreat of the social state. When the sanctuary movement first surged in the 1980s, explicitly left-wing political projects like the Black Panthers faced waves of violent police repression. This created a political vacuum that churches with left leanings could exploit, due the kind of discursive and legal protections they enjoy. So, when growing numbers of refugees began to arrive in the US as a result of the civil wars in Central America, these churches formed a sanctuary movement.

In the early years of the movement, religious communities simply offered first aid — shelter, food and the like. But with both faith-based community-building and the illegalization of migration on the rise, the step to provide further protection to migrant communities was not too far off. Throughout the 1990s the notion gradually developed into a more explicitly political concept, with different actors no longer just requesting shelter but increasingly claiming a right to full participation in the everyday life of the city.

Sanctuary Cities in Europe

In 2005, the political — rather than religious — concept made its way to Anglophone Europe, with an alliance of grassroots movements in Ireland and the UK pushing for collective urban hospitality for refugees, starting with the City of Sanctuary organization founded in Sheffield that year. By 2007, the activist platform had managed to implement the first legal changes in Sheffield and beyond.

In the next years, the concept spread to the European continent, where a variety of factors were radically changing the political landscape. For starters, the Arab Spring opened Europe’s external borders to refugees and migrants from different African states, enabling large migration flows that had previously been held back by agreements between the EU and local dictators. At the same time, the countries where most refugees arrived — Greece, Italy and Spain — were hit particularly hard by the consequences of the global financial crisis. Due to the so-called Dublin Regulation, an EU law that regulates member-state responsibilities for asylum seekers, these countries were pretty much left to deal with the sudden increase in arrivals by themselves, even as they were forced to implement rigorous austerity programs, stripping their population of much-needed social security and public services.

These conditions in turn led to the development of different mutual aid projects and solidarity campaigns. Athens is known for its solidarity clinics, Barcelona developed solidarity housing projects, and Naples institutionalizes the cooperation with social movements — to name but a few. Throughout this process, the term sanctuary was sometimes replaced with the more fitting term solidarity. As in the US, the composition of social forces behind these different sanctuary and solidarity cities varies widely. The mayor of Naples, for instance, seeks to enable a diversity of solidarity initiatives, the anarchist movement in Athens runs self-managed squats, and different social movement organizations in Barcelona are participating in the local government.

In all of these cities, however, new initiatives emerged that did not focus purely on undocumented people, but on all people who are excluded from the everyday life of the city. It is this imaginary of solidarity that is currently also animating our municipal project in Berlin.

Conditions in Germany: Between Image and Reality

Living an illegalized life in Germany is very hard, if not impossible, to accomplish. Legal and historical developments created a particular terrain for refugees and, with it, for solidarity city initiatives. Spoiler alert: Germany has a history of xenophobia. “Not to be a land of immigration” was, for the longest time, part of the country’s national identity — also after the war. Even when programs were developed to attract foreign workers, needed for the rapidly growing industry of the 1950s and 1960s, these workers were defined as “guest workers” (in the West) or “contractors” (in the East) who were expected to leave after their work in Germany was completed. As a result, both German states followed exceedingly strict policies of segregation and ghettoization.

The anti-immigration state discourse is reflected in legal conditions that are relevant for the solidarity city concept. It starts with Germany’s blood-bond citizenship, as opposed to the soil-bond citizenship of the United States, that makes it very hard for people to leave the precarious status of illegality through a safety net built by families. Another obstacle is the asylum legislation. Although the right is established in the constitution, it is nearly impossible to be granted asylum in today’s Germany. Since the early 1990s, any person who entered a “safe third country” before reaching Germany will be deported back to that state. What this means in practice is that, if you did not manage to get a direct flight from your respective homeland in crisis to Germany, including all the required papers, stamps and visa, the German state will do everything in its power to prevent you from establishing an existence here. And the state’s tools are simple: it refuses to provide work permits, limits freedom of movement to a single municipality (sometimes a state), blocks access to education, and provides only very limited and defective shelter, often in isolated large camps.

The combination of the long-standing segregation between migrant and non-migrant communities and the extreme restrictions faced by asylum-seekers and refugees in everyday life creates extreme obstacles to successful self-organization. And yet despite these challenges, refugees began to massively self-organize around 2013 (although there had been various attempts before that time, they mostly did not reach the same level of success). One of the most important steps in 2013 was to move from the remote camps provided by the state into the city centers. Churches, squares, parks, monuments and abandoned school buildings became the spaces where asylum-seekers and refugees established a new social visibility. From there, the struggle grew exponentially: by 2015, as millions of refugees and undocumented migrants arrived on Europe’s shores, every city in the country had some kind of welcoming initiative. The emergency shelters closed their doors to volunteers as there were just too many. On the night of September 4, these solidarity efforts went viral when Angela Merkel and her Austrian counterpart let trains full of refugees pass the borders from Hungary for one day.

So, all’s well that ends well, then? Hardly. While the pictures of welcoming Germans looked good on camera, the reality was quite different. Every small concession that refugees and undocumented people — along with their supporters — obtained was answered with a hard backlash: less than three weeks after Merkel supposedly opened the borders, the federal government implemented another set of cutbacks on the right to asylum, leading to mass deportations of ethnic minorities to the newly defined “safe states” of Albania, Montenegro and Kosovo, where many had suffered from violent oppression.

There are countless examples for such back-and-forths. In January 2015, limitations on the freedom of movement were abolished, only to be re-introduced in November, this time with the possibility to immediately deport people who leave their designated municipality more than once. Similar developments took place over the past two years, with changes in allowances, access to education, special protection for unaccompanied minors, and so on. The latest reform from May 2017 introduces massive invasions into the privacy of refugees (such as random cellphone searches), increased “detention pending deportation” and ankle monitors. These legal changes are small steps in a long and ongoing process towards the total abolition of the right to asylum in Germany. Despite huge waves of support and sympathy from society, the actual legal conditions for the vast majority of refugees have dramatically worsened over the last years.

Solidarity City Berlin

It has become clear, then, that even mass mobilizations in solidarity with refugees were not enough to get us anywhere. The state has adapted to our tactics: demonstrations were simply allowed to move peacefully through the city, slowing down traffic here and there, but not leading to any real political change. The squatting of an old school building provoked a short, extreme reaction, but when the state realized that eviction was not a feasible option it changed its strategy, waiting the squatters out until public attention passed on.

With a federal government that had time on its side, and successfully developed a façade of “caring” about refugees, we, too, needed a new idea, a new discourse, a new strategic response. With cities in Southern Europe struggling for solidarity in times of extreme austerity, and with North American movements working on strategies to protect their undocumented community members, we had good examples for the development of a new battle plan; one that focuses on the right to move, live, learn or work in our city. We “simply” had to adapt these ideas to our local conditions.

We quickly discovered that, within our city and our everyday lives produced in it, we are able to find answers to very general political questions, such as the issue of political subjectivity under the conditions of social fragmentation produced by neoliberalism. The subjectivity we aim to mobilize is simply our neighbors — people who live in the same urban space. We don’t have to construct a shared history, because we define our “we” through our shared everyday space. Some definitions change with this new strategy, first of all the divisions between refugees, undocumented people and citizens. With the changes in asylum legislation, it is only a matter of time until many refugees become illegalized — but beyond that, we share many problems experienced in our everyday lives relating to the consequence of austerity, gentrification or even changes in labor laws.

With this less strict separation of actors comes the understanding that deportations, as executions of German national asylum legislation, are just part of the wider problem that we identify as European neoliberalism. With its need for surplus labor it leads to the erosion of the social state, workers’ protections and affordable housing, forces people to move from the South to the North, and leaves us all to fight over the bread crumbs. In short: among our neighbors, we can find a variety of oppressed groups that quite often share very similar experiences of everyday life in the city.

With this less strict separation of actors comes the understanding that deportations, as executions of German national asylum legislation, are just part of the wider problem that we identify as European neoliberalism. With its need for surplus labor it leads to the erosion of the social state, workers’ protections and affordable housing, forces people to move from the South to the North, and leaves us all to fight over the bread crumbs. In short: among our neighbors, we can find a variety of oppressed groups that quite often share very similar experiences of everyday life in the city.

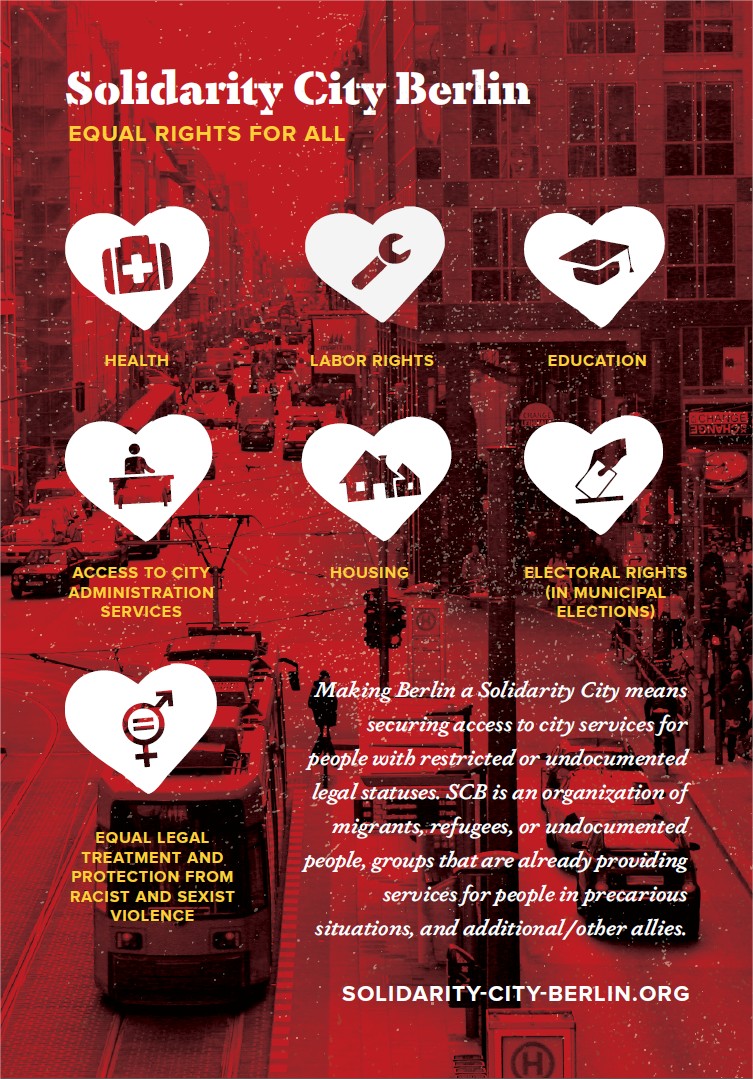

What we needed for this idea to become a useful strategy was a formalized space to develop more concrete ideas. With the help of comrades from No One Is Illegal in Toronto we created this space through the formation of an alliance. Its member organizations, largely consisting of refugees and undocumented people, remained focused on questions around a precarious residency status — not because we think that residency is the only problem people face, but because it is a factor that makes many other fights harder. In debates and inquiries, we began to identify that the most important fields for the undocumented and refugees in our alliance could be divided into five fields: health, education, work, housing and protection from and by the law.

We then decided to develop policy proposals for each of these issue areas, answering the questions: “What are the concrete problems?” and “What would concrete solutions for these problems in Berlin look like?” Answering these questions involved doing research and it also meant looking for small, possible reforms. Beginning with the issue area of health, we have so far reached a pretty clear understanding of the possibilities to provide healthcare coverage for everyone in Berlin, including some clear and simple outlines for a potential system to be put in place.

A Model of Urban Self-Governance

By producing concrete proposals, we are able to approach political decision-makers and force them to position themselves around our key demand. “No borders, no nations?” All for it. But the mayor of Berlin isn’t, and most people have no way to imagine a world without nations. Denying children the ability to receive healthcare, on the other hand, is much harder to sell to your electorate. With the understanding that our community consists of all our neighbors, we then make this unifying idea a guideline for further research. We try to develop policy proposals that, first, do not allow for a separation based on residency status, and second, serve as stepping stones to make the voice of social movements heard, in order to better protect ourselves from the backlashes that have tainted past successes.

For health, this involves demanding universal coverage for people without insurance, whether they are undocumented, come from another European state, or have just fallen through the cracks of the system for whatever reason. It also means that we want to participate in a newly developed institution, like an advisory board composed of neighbors and social actors. This allows us to consolidate our achievements in healthcare provision but also to slowly co-construct a more participatory form of urban self-governance. If local institutions become more and more democratically controlled, this in return allows for further social mobilization and the participation of larger groups of people in local politics. Our horizon for Berlin would therefore be to develop a complex of participatory institutions that allow us to learn, live and work in our future sanctuary.

With similar problems all over Europe and beyond, parallel ideas developed. Terms such as cities of change, rebel cities or solidarity cities stand for different attempts to connect cities with similar imaginations of a radical urban future. Instead of running against slow and powerful federal governments or trying to change the neoliberal base of the European Union, the idea is to create something like a confederation of cities, pushing for change outside or rather parallel to larger governmental structures. Such attempts have an extensive history in Europe, where cities have long been the place of liberation, sanctuary, and yes, citizenship. If we take into account the fact that 70-75 percent of the European population lives in urban spaces, it is not too hard to imagine that important changes will be effected by this key demographic. Cities, to us, are the first step — or a parallel move, rather — in a broader conquest of democracy that can eventually begin to erode the nation-state and the European Union as we know it.

Sounds more like a dream of the future? Absolutely, but it is a dream worth fighting for — and one that can be divided into small, feasible steps. Perhaps we shouldn’t even call it a dream, but rather a political horizon we can work towards together. With such a shared horizon in our minds we can — and should — begin to coordinate our different efforts, contextualize the local fights we win and put these small victories to work within our larger frame.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/urban-sanctuary-solidarity-cities-refugees/

Next Magazine article

Cities Against the Wall

- Carlos Delclós

- July 21, 2017

Pacifying the Neighborhood

- Tucker Landesman

- July 21, 2017